SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Surveillance forces journalists to think and act like spies

Published

7 years agoon

Once upon a time, a journalist never gave up a confidential source. When someone comes forward, anonymously, to inform the public, it’s better to risk time incarcerated than give them up. This ethical responsibility was also a practical and professional necessity. If you promise anonymity, you’re obliged to deliver. If you can’t keep your word, who will trust you in the future? Sources go elsewhere and stories pass you by.

Grizzled correspondents might recall this time with nostalgia. For many young journalists, it’s more like historical fiction–a time when reporters could choose not to give up a source, gruff editors chain-smoked cigars, and you could spot a press hack by the telltale notebook and card in the brim of a hat.

The experience of a new generation of news writers tells a different story. Whether you choose to yield a source’s name is secondary. Can you even protect your source to begin with? Call records, email archives, phone tapping, cell-site location information, smart transit passes, roving bugs, and surveillance cameras–our world defaults to being watched. You can perhaps achieve privacy for a few fleeting moments, but, even then, only with a great deal of effort.

Yet this is journalism’s brave new world. In the United States, the National Security Agency, otherwise known as the NSA, seeks to listen to every electronic communication sent or received. In the U.K., the Government Communications Headquarters, or GCHQ, has succeeded in intercepting and storing every peep that passes over the wires. Commercial spy software FinFisher (also called FinSpy) monitors citizens in at least 20 other countries, according to a report by The Citizen Lab, a research group based at the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto in Ontario, Canada. Global Information Society Watch’s global report details the state of communications surveillance in plenty more. Even Canada’s spy agency may be watching Canadians illegally, though the GISWatch report could not say so conclusively.

If journalists can protect the identity of their sources at all, it’s only with the application of incredible expertise and practice, along with expensive tools. Journalists now compete with spooks and spies, and the spooks have the home-field advantage.

Shadowy worlds of subterfuge and surveillance should not be a journalist’s habitat. The time journalists spend learning to play Spy-vs.-Spy could be better spent honing their craft. Every hour spent wrangling complex security tools could be an hour spent researching and writing. All the staff on a newsroom’s security team could be writers and editors instead. Each geeky gizmo and air-gapped computer (a computer that is never connected to a network) could be another camera or microphone, or the cost could be spent on payroll. All the extra labor and logistics dedicated to evading espionage is a loss.

This poses sometimes-steep financial costs on newsrooms. If journalists and media organizations are to protect themselves, they must buy more tools and adopt practices that limit their efficiency. Robust security practices are complex and time-consuming, imposing logistical costs. The psychological toll of constant surveillance leads to exhaustion and burnout. Few journalists do their best work when they know that government thugs could break down the door at any moment–as they did at the home of independent New Zealand reporter Nicky Hager in October 2014, according to The Intercept.

Many have worked to slow the swing of the pendulum from privacy to panopticon, increasing development of anti-surveillance tools and advice for journalists. The response to widespread knowledge of the long arm of the surveillance state has been gradual but impressive. Developers have increased work on surveillance–resistance projects and anonymous tip lines. Experts have put together numerousdigital security guides and training programs, all intended to help reporters from falling under the focused gaze of government surveillance.

Perhaps the flagship of this proliferation is SecureDrop, a secure and anonymous submission system for journalists. First pioneered by the former hacker and current digital security journalist Kevin Poulsen and the late programmer and political activist Aaron Swartz under the moniker DeadDrop, SecureDrop is intended to allow potential sources or whistleblowers to get in touch with journalists without leaving any dangerous records of their identity.

SecureDrop combines several pieces of security and privacy software into an integrated system, ensuring that only the journalists can read anonymous tips. Messages are protected with PGP, the tried-and-true gold standard for this task. Sources’ anonymity is provided by Tor, the anonymity network that underpins private communications for everyone from the U.S. Navy and CIA to large businesses and survivors of domestic abuse. The result is safely encrypted messages and no metadata trail. With SecureDrop, journalists don’t just choosenot to reveal a source’s identity. Unless sources choose to reveal their identity, the reporters could not unmask sources even if they tried.

Initially just an idea and some prototype code, SecureDrop was mostly theoretical until early 2013. The first major deployment was at The New Yorker. The project was soon adopted by the nonprofit Freedom of the Press Foundation, which was founded with the specific mission of facilitating journalism that governments oppose. FPF, as the foundation is known, soon took over SecureDrop’s development and maintenance, as well as outreach and funding. More than a dozen other news organizations and prominent journalists have now deployed SecureDrop. With an ongoing crowdfunding campaign, FPF plans to bring it to many more.

SecureDrop works hard to evade even targeted attacks and surveillance. Making use of cutting-edge technology and contemporary security best practices, SecureDrop separates different tasks onto different computers. Each machine only performs part of the puzzle, so it’s very difficult to compromise the whole system at once.

This makes SecureDrop quite expensive to deploy. FPF estimates that a single SecureDrop installation would set a newsroom back around $3,000, which is a lot to ask for a tool designed to protect the most important of tips from the most advanced of snoops.

Other organizations have developed and distributed best practices and training materials. Universities have deepened their research into the threats journalists face. The Citizen Lab, already discussed in this piece, is dedicated to deep research about how technology and security affect human rights and is the source of some of the most detailed and comprehensive technical reports of recent years. If you want to know about the threats facing journalists and human rights groups, Citizen Lab is the place to go.

Yet, as deep as Citizen Lab’s work goes, it is as likely to induce security nihilism as it is to produce savvy security practices. An August 2014 report tells of terrifying new tools for state attacks on the media. Called “network injection appliances,” these devices insert malicious software into otherwise innocuous traffic. Used right, one can modify an online video, adding malware that takes over a journalist’s computer. If a journalist is using a service such as YouTube or Vimeo, session cookies allow the journalist to be targeted precisely. This makes these attacks very difficult to detect and prevent.

With this new technology, journalists don’t have to make a mistake to be compromised. Gone are the phishing days of opening a malicious attachment or clicking a suspicious link. There’s no trap to notice and avoid. Just browsing the Web puts one at risk, and avoiding online video is an impractical ask of a journalist conducting research. Network injection appliances have likely already been deployed in Oman and Turkmenistan, according to Citizen Lab, and because they’re commercially developed by private companies, the price of these devices will only continue to drop as their capabilities expand.

Another Citizen Lab paper paints a disturbing picture of government cyberattacks. Journalists, among the principal victims of this sort of technological espionage, face state-level threats while lacking the funds and expertise to protect themselves. Attacks on computer systems can reach across borders into seemingly safe locations, allowing attackers to disrupt communications and impairing journalists’ ability to do their core work. Sometimes attacks are simply a nuisance or a resource drain; at other times they present major risks to individuals’ safety.

It’s all but impossible for journalists to learn the strategies of the state and appropriate countermeasures on a shoestring budget. Websites and service providers are often better positioned to protect journalists from these attacks. Securing the everyday tools of the trade works much better than does demanding that journalists jump through arcane hoops to stay safe. Simple measures can go a long way. Just enabling secure HTTPS rather than insecure HTTP can make a huge difference. The New York Times has called on all news sites to adopt this very measure by the end of 2015.

As noted security expert The Grugq puts it: “We can secure the things people actually do, or we can tell them to do things differently. Only one of these has any chance of working.”

Since we first saw Edward Snowden’s face, in 2013, computer-security guides for journalists have multiplied, but using computers safely is hard when a government is trying to get the drop on you. Many guides only scratch the surface, detailing basic–but important–steps. Turning on automatic software updates or using password managers and two-factor authentication for online accounts make a big difference. These first steps make journalists slightly harder to attack.

In fact, simple practices probably have a greater impact than do more complex ones. Esoteric security strategies are a lot of work and sometimes only inconvenience a savvy attacker. Simple measures completely stymie simple attacks and force advanced attackers to change their tactics. A sophisticated attacker will never use an advanced technique when a simple one will do. More sophisticated attempts require more work, cost more, and are more prone to detection. Changing the game by forcing attackers to use scarce resources helps everyone stay safe.

Other guides delve deeply into advanced principles of operational security. Abbreviated “OPSEC,” the term is military jargon for measures taken to keep critical information out of hostile hands. If the phrase sounds more at home in a spy thriller than in a journalism manual, that’s a hint at the problems posed by press surveillance. Mainstream journalists and press organizations openly acknowledge their need to learn spies’ tactics and techniques to stay a step ahead.

The adoption of military tactics and an espionage mindset has a substantial downside. The Grugq explains: “OPSEC comes at a cost, and a significant part of that cost is efficiency. Maintaining a strong security posture … for long periods of time is very stressful, even for professionally trained espionage officers.”

Yet even in apparently free democratic societies, compromising a free press is the day-to-day work of the security services.

Intelligence services sometimes target journalists for surveillance, even when the missions of the agencies involved are ostensibly centered around foreign intelligence. Iranian spies orchestrate elaborate campaigns to bamboozle journalists; they even pose as journalists when targeting think tanks and lawmakers, Wired has reported. The FBI has also admitted using the latter tactic and actually defended it publicly when criticized. In the U.K., security services have abandoned restraint when it comes to surveillance of journalists and civil society, Ryan Gallagher wrote in The Intercept, summarizing: “An investigative journalist working on a case or story involving state secrets could be targeted on the basis that they are perceived to be working against the vaguely defined national security interests of the government.”

*****

Some journalists have risen to this challenge. After meeting with Snowden, Laura Poitras and Glenn Greenwald realized that traditional newspapers and media groups were not well suited to this world of watchers. They needed a new sort of organization–one ready to play spy games with professional spies from the very start.

They founded the First Look Media group with help from fellow investigative journalist Jeremy Scahill and funding from eBay mogul Pierre Omidyar. First Look’s flagship online magazine, The Intercept, is dedicated to exposing the abuses of the surveillance state. Choosing such powerful foes meant that The Intercept had to stay one step ahead from the start.

Micah Lee is The Intercept‘s resident security expert. Formerly a staff technologist at technology civil rights group the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Lee was on The Intercept team from the beginning. He designed and implemented the security measures that Greenwald, Poitras, and Scahill–and now a team of 20–use to stay safe. When asked about the infrastructure needed to protect the publication, he frankly admitted: “When we think it’ll make us safer, we normally just buy another computer or device. We’re willing to spend money on these things when there’s a clear security benefit.”

Lee was referring to security practices typically only needed when one is facing adversaries with the sophistication of governments. Protecting important information on separate air-gapped computers is a common practice at The Intercept. Lee and other technologists are fond of a security principle called “defense in depth,” an approach that assumes that some security measures will fail and calls for systems that remain secure even when that happens. In the planning for defense in depth, a process should become insecure not when onesecurity measure fails but instead when dozens do.

Systems built this way demand more hardware than do those where security is more brittle. Several computers ensure that the compromise of one will leave the others safe. Smartcards protect cryptographic keys even when other things go wrong. All of this tech costs money and requires experienced technologists like Lee to design and operate.

In keeping with this level of prudent paranoia, Lee and his colleagues often eschew regular smartphones in favor of the CryptoPhone. These $3,500 devices, made by German manufacturer GSMK, don’t just provide encrypted calls; they’re heavily customized and locked-down Android devices loaded with a whole host of custom software. They even try to detect anomalies in cellular networks that might be indicative of an attack or targeted surveillance.

These practices and this technology are the best that media organizations can buy. It’s a far cry from the James Bond-esque gadgetry that one might see at MI6 or the CIA, but, used correctly, it can keep the spooks at bay long enough for you to meet with sources and write the stories that need to be written.

Staff at The Intercept use PGP for email encryption by default. Lee estimates that more than 80 percent of the emails he sent in the last six months were encrypted in this way. For most people who aren’t security experts, PGP is a niche tool with a notoriously steep learning curve. Getting started requires hours of training and practice to wrap one’s head around complex and unintuitive principles of public-key cryptography. The process takes even longer if one doesn’t have an experienced guide.

Between building sustainable long-term security strategies and jetting around protecting the magazine’s VIP writers, Lee quickly ran out of the time needed to show each new hire how to use PGP. But he noticed that he wasn’t always needed: “Folks learn PGP the same way they do any other tricky technical thing–they Google it, or they ask their nerd friends, and sometimes they get bad advice,” he said. At The Intercept, new hires were learning PGP from folks already there–journalists and editors as well as technologists.

The Intercept had developed what Lee calls a “security culture,” an operational security term that has its roots in activism. In a “security culture,” a community adopts customs and norms that protect its members. It’s a wholesale adoption of operational security practices into the everyday work and activities of the group. The Intercept team considers security a core value, so people there are willing to work together to protect one another, even when that’s outside their usual work.

“Of course, having Erinn in New York helps, too,” Lee joked, referring to Erinn Clark, the most recent member of First Look’s security team. Clark came to First Look from the Tor Project, the nonprofit group responsible for developing Tor. Another security virtuoso, Clark is more than familiar not only with the nitty-gritty of security tools but also with the adoption of secure practices across an organization. In technology circles, the Tor Project is famous both for the exotic ways in which states have tried to infiltrate and attack it and for the extreme security measures its members have adopted to protect themselves.

Leading the incredible heavy hitters of First Look’s security team is Morgan “Mayhem” Marquis-Boire. A security superstar, Marquis-Boire worked on Google’s security incident-response team, and he is a senior researcher at The Citizen Lab. This incredible brain trust isn’t just there to keep just First Look safe. Once First Look’s basic security needs are met, the group plans to branch out. “We want the security team to start developing tools and hardware and doing bigger research.” Lee said. The team members plan to use their skills and expertise to help other organizations that can’t afford their own elite security teams.

The challenge is always resources. First Look has a billionaire on call to pay for the latest technology and fancy technologists. This is a rarity. Other journalists may face a stark choice between hard-hitting stories and staying safe.

What does information security look like at publications that don’t have First Look’s billionaire funding? FPF regularly sends technical experts to help newsrooms install, set up, and upgrade SecureDrop. Every time they set foot in a newsroom, FPF techs find themselves flooded with security questions from reporters and editors. Questions aren’t just about SecureDrop or FPF; news teams want to know about everything from the ins and out of other tools, such as OTRand Tails, to the sort of advanced operational security measures that can help them keep their heads above water when spies come snooping.

Runa A. Sandvik, a member of FPF’s technical team, said, “Even if you wanted to use these tools and had all the patience to learn them, there’s still so much conflicting information–it’s very confusing, very intimidating.” And though few media organizations have the ability to hire technologists to work with their reporting staffs, Sandvik notes that the situation for journalists not affiliated with a major organization is even bleaker: “If you have a technologist, someone to help you, that’s one thing. If you’re freelance and not overly technical, I don’t know how you’re going to work this stuff out.” She added, “Many feel overwhelmed; they don’t know who to ask for help.”

Just having a technologist to help with analysis and security may not be enough. The newsroom has to commit to understanding the issues and taking good advice. Barton Gellman, who currently writes for The Washington Post, was one of the recipients of the document cache Snowden assembled, and he knew that he didn’t have the technical skills to work on the documents alone. He brought prominent security researcher Ashkan Soltani (now chief technologist for the Federal Trade Commission) on board to help. Soltani bolstered Gellman’s security practices and helped Gellman analyze and understand the more technical material in the collection.

To make matters worse, intelligence agencies encourage confusion and misunderstanding when it comes to secure tools and practices. They try to associate a need for privacy with wrongdoing. This association makes it even harder for journalists to protect themselves and their sources. Persuading sources to protect themselves is harder when the tools of safety are associated with suspicion. In some cases, making secure tools seem suspicious actively endangers sources who live in less tolerant environs, such as dissidents in mainland China who use Tor. This doublethink is a strange flip side to the surveillance state: First, watch everyone, always, then vilify any attempt to recover some privacy. This is especially disruptive to journalists and their ability to serve as watchdogs.

Even without state propaganda and unforced errors, covert action takes a substantial toll on the press’s ability to hold leaders accountable. Espionage targeting journalists and their sources impairs the healthy function of the states where it occurs. And these practices are not just a feature of regimes known to be restrictive or autocratic.

In 2013, David Miranda was detained for most of a day while making a connection between flights at Heathrow Airport in London. Miranda was changing planes on a journey from Germany to Brazil on which he was transporting documents and video footage between Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras. British police held him under measures designed to combat terrorism. Their reasoning? Miranda was promoting a “political or ideological cause.”

In July 2013, surveillance agency GCHQ destroyed computers at the Guardiannewspaper in London. The security agency had already threatened the newspaper’s editors, demanding that the Guardian stop reporting on government surveillance. A security service literally knocked on the doors of a prominent and critical newspaper in Western Europe. They ground a computer into pieces with the use of power tools. All of this was done in a vain attempt to prevent the publication of more articles on a topic that discomfited the government.

These are the tools the state has at its disposal to discourage dissent. It is understandable that, for some, the risk of challenging this authority is simply too great. When these are the consequences of hard-hitting reporting, sticking to “safe” topics and innocuous pieces is a reasonable response.

But even for those who choose to continue the hard work of comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable, evading the panopticon comes at a tremendous cost. There are the costs incurred in avoiding simple tools in favor of secure ones. The costs of using extra hardware to protect sensitive materials. The costs of hiring elite security teams instead of extra editors. The costs of worrying that you’ve made a mistake in your security measures. The costs of wondering whether your hotel room will be undisturbed when you get back. The costs of hoping that today isn’t the day that a government agent knocks at the door and asks to destroy your work, or worse.

When journalists must compete with spies and surveillance, even when they win, society loses.

DISCLOSURE: The author previously worked at the Tor Project, the non-profit organization responsible for developing and maintaining the Tor software and network

Tom Lowenthal is CPJ’s resident expert in operational security and surveillance self-defense. He is also a freelance journalist on security and tech policy matters.

Related posts:

Sigh of relief as Red Pepper Journalists are released on bail

Sigh of relief as Red Pepper Journalists are released on bail

NGOs in Ukraine call to dismiss the intelligence services’ plan to install any kind of surveillance equipment

NGOs in Ukraine call to dismiss the intelligence services’ plan to install any kind of surveillance equipment

Manipulating Social Media to Undermine Democracy

Manipulating Social Media to Undermine Democracy

Journalists under duress: Internet shutdowns in Africa are stifling press freedom

Journalists under duress: Internet shutdowns in Africa are stifling press freedom

You may like

DEFENDING LAND AND ENVIRONMENTAL RIGHTS

Statement: The Energy Sector Strategy 2024–2028 Must Mark the End of the EBRD’s Support to Fossil Fuels

Published

10 months agoon

September 27, 2023

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) is due to publish a new Energy Sector Strategy before the end of 2023. A total of 130 civil society organizations from over 40 countries have released a statement calling on the EBRD to end finance for all fossil fuels, including gas.

From 2018 to 2021, the EBRD invested EUR 2.9 billion in the fossil energy sector, with the majority of this support going to gas. This makes it the third biggest funder of fossil fuels among all multilateral development banks, behind the World Bank Group and the Islamic Development Bank.

The EBRD has already excluded coal and upstream oil and gas fields from its financing. The draft Energy Sector Strategy further excludes oil transportation and oil-fired electricity generation. However, the draft strategy would continue to allow some investment in new fossil gas pipelines and other transportation infrastructure, as well as gas power generation and heating.

In the statement, the civil society organizations point out that any new support to gas risks locking in outdated energy infrastructure in places that need investments in clean energy the most. At the same time, they highlight, ending support to fossil gas is necessary, not only for climate security, but also for ensuring energy security, since continued investment in gas exposes countries of operation to high and volatile energy prices that can have a severe impact on their ability to reach development targets. Moreover, they underscore that supporting new gas transportation infrastructure is not a solution to the current energy crisis, given that new infrastructure would not come online for several years, well after the crisis has passed.

The signatories of the statement call on the EBRD to amend the Energy Sector Strategy to

- fully exclude new investments in midstream and downstream gas projects;

- avoid loopholes involving the use of unproven or uneconomic technologies, as well as aspirational but meaningless mitigation measures such as “CCS-readiness”; and

- strengthen the requirements for financial intermediaries where the intended nature of the sub-transactions is not known to exclude fossil fuel finance across the entire value chain.

Source: iisd.org

Download the statement: https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2023-09/ngo-statement-on-energy-sector-strategy-2024-2028.pdf

Related posts:

Breaking: over 350,000 acres of land were grabbed during Witness Radio – Uganda’s seven months ban.

Breaking: over 350,000 acres of land were grabbed during Witness Radio – Uganda’s seven months ban.

EBRD launches new agribusiness strategy

EBRD launches new agribusiness strategy

30 civil society organizations have written to the World Bank Group demanding to publicly disclose the Africa Energy Approach paper.

30 civil society organizations have written to the World Bank Group demanding to publicly disclose the Africa Energy Approach paper.

Over 600 million Africans lack electricity despite huge renewable energy potential

Over 600 million Africans lack electricity despite huge renewable energy potential

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

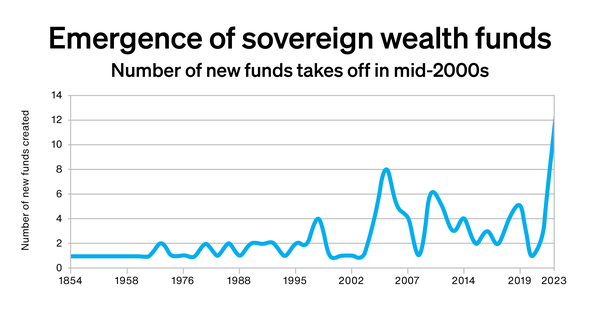

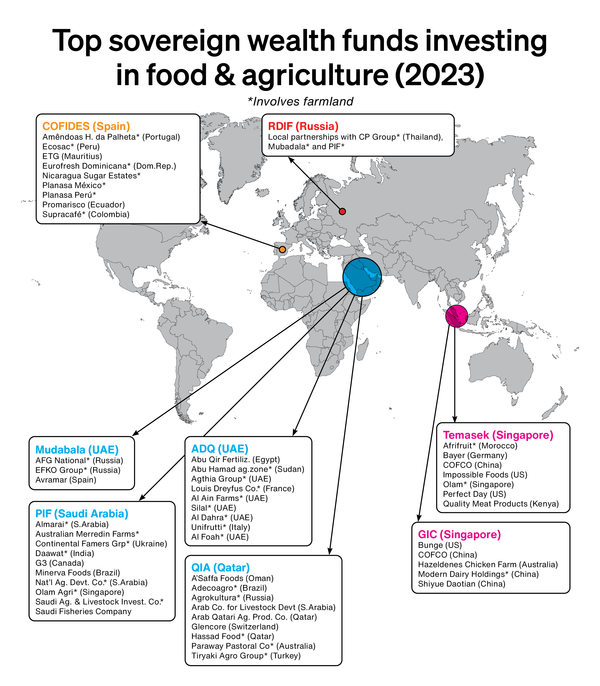

Will more sovereign wealth funds mean less food sovereignty?

Published

1 year agoon

April 13, 2023

- 45% of Louis Dreyfus Company, with its massive land holdings in Latin America, growing sugarcane, citrus, rice and coffee;

- a majority stake in Unifrutti, with 15,000 ha of fruit farms in Chile, Ecuador, Argentina, Philippines, Spain, Italy and South Africa; and

- Al Dahra, a large agribusiness conglomerate controlling and cultivating 118,315 ha of farmland in Romania, Spain, Serbia, Morocco, Egypt, Namibia and the US.

|

Sovereign wealth funds invested in farmland/food/agriculture (2023)

|

|||

|

Country

|

Fund

|

Est.

|

AUM (US$bn)

|

|

China

|

CIC

|

2007

|

1351

|

|

Norway

|

NBIM

|

1997

|

1145

|

|

UAE – Abu Dhabi

|

ADIA

|

1967

|

993

|

|

Kuwait

|

KIA

|

1953

|

769

|

|

Saudi Arabia

|

PIF

|

1971

|

620

|

|

China

|

NSSF

|

2000

|

474

|

|

Qatar

|

QIA

|

2005

|

450

|

|

UAE – Dubai

|

ICD

|

2006

|

300

|

|

Singapore

|

Temasek

|

1974

|

298

|

|

UAE – Abu Dhabi

|

Mubadala

|

2002

|

284

|

|

UAE – Abu Dhabi

|

ADQ

|

2018

|

157

|

|

Australia

|

Future Fund

|

2006

|

157

|

|

Iran

|

NDFI

|

2011

|

139

|

|

UAE

|

EIA

|

2007

|

91

|

|

USA – AK

|

Alaska PFC

|

1976

|

73

|

|

Australia – QLD

|

QIC

|

1991

|

67

|

|

USA – TX

|

UTIMCO

|

1876

|

64

|

|

USA – TX

|

Texas PSF

|

1854

|

56

|

|

Brunei

|

BIA

|

1983

|

55

|

|

France

|

Bpifrance

|

2008

|

50

|

|

UAE – Dubai

|

Dubai World

|

2005

|

42

|

|

Oman

|

OIA

|

2020

|

42

|

|

USA – NM

|

New Mexico SIC

|

1958

|

37

|

|

Malaysia

|

Khazanah

|

1993

|

31

|

|

Russia

|

RDIF

|

2011

|

28

|

|

Turkey

|

TVF

|

2017

|

22

|

|

Bahrain

|

Mumtalakat

|

2006

|

19

|

|

Ireland

|

ISIF

|

2014

|

16

|

|

Canada – SK

|

SK CIC

|

1947

|

16

|

|

Italy

|

CDP Equity

|

2011

|

13

|

|

China

|

CADF

|

2007

|

10

|

|

Indonesia

|

INA

|

2020

|

6

|

|

India

|

NIIF

|

2015

|

4

|

|

Spain

|

COFIDES

|

1988

|

4

|

|

Nigeria

|

NSIA

|

2011

|

3

|

|

Angola

|

FSDEA

|

2012

|

3

|

|

Egypt

|

TSFE

|

2018

|

2

|

|

Vietnam

|

SCIC

|

2006

|

2

|

|

Gabon

|

FGIS

|

2012

|

2

|

|

Morocco

|

Ithmar Capital

|

2011

|

2

|

|

Palestine

|

PIF

|

2003

|

1

|

|

Bolivia

|

FINPRO

|

2015

|

0,4

|

|

AUM (assets under management) figures from Global SWF, January 2023

|

|||

|

Engagement in food/farmland/agriculture assessed by GRAIN

|

|||

Related posts:

La Via Campesina calls on States to exit the WTO and to create a new framework based on food sovereignty

La Via Campesina calls on States to exit the WTO and to create a new framework based on food sovereignty

The United Nations Food Systems Summit is a corporate food summit —not a “people’s” food summit

The United Nations Food Systems Summit is a corporate food summit —not a “people’s” food summit

Food Sovereignty: A Manifesto for the Future of Our Planet

Food Sovereignty: A Manifesto for the Future of Our Planet

CORPORATE AGRIBUSINESS GIANTS SWIM IN WEALTH AS MORE POOR PEOPLE GO HUNGRY AMID THE BITING COVID PANDEMIC.

CORPORATE AGRIBUSINESS GIANTS SWIM IN WEALTH AS MORE POOR PEOPLE GO HUNGRY AMID THE BITING COVID PANDEMIC.

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Farmland values hit record highs, pricing out farmers

Published

2 years agoon

November 21, 2022

Oil activities in Murchison Falls National Park threaten Wildlife Conservation – AFIEGO study reveals.

A Financial gap: Can China be stopped from financing the EACOP?

NEMA suspend operations to evict the World Bank project-affected community and other residents accused of being located in wetlands.

Farmers count losses as dry spell scorches maize gardens

Sexual violence as a tool to grab land: a local woman accuses industrial agriculture investor Agilis Partners Limited of sexual violence.

Thirty-six (36) groups from all over the world have written to industrial agriculture investors, Agilis Partners Limited to stop human rights violations/abuses against thousands of indigenous/local communities, settle grievances, and return the grabbed land.

CSOs, oil host communities, and concerned citizens have petitioned the President of Uganda to stop oil drilling in the Murchison Falls National Park.

Enemies of the State: Resistance to the EACOP becomes a deadly task

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days agoNEMA suspend operations to evict the World Bank project-affected community and other residents accused of being located in wetlands.

-

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago

FARM NEWS2 weeks agoStrengthening Small-Scale Farming in Uganda through Farmer Field Schools.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days agoOil activities in Murchison Falls National Park threaten Wildlife Conservation – AFIEGO study reveals.

-

NGO WORK1 week ago

NGO WORK1 week agoThe mothers and daughters of the global south cannot celebrate the World Bank’s 80-year legacy of harm.

-

FARM NEWS5 days ago

FARM NEWS5 days agoFarmers count losses as dry spell scorches maize gardens

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoNEMA hindering environment restoration in Wakiso – leaders

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days agoA Financial gap: Can China be stopped from financing the EACOP?