WITNESS RADIO MILESTONES

Media “switch-off” in Kenya: a looming threat to pluralist society

Published

8 years agoon

Guest post by Grace Mutung’u (@bomu)

On Tuesday, January 30, the Communications Authority of Kenya switched off three main television stations and a local language channel ahead of a mock swearing-in ceremony for opposition leader Raila Odinga. A day later, the “switch-off” was extended indefinitely as the government proceeded with investigations into the role of the media in broadcasting the swearing-in ceremony, which the government considers an illegal act. Okiya Omtata, a human rights activist, obtained court orders requiring that TV broadcasting be restored, with no more interference until the case is heard and a legal determination is reached. One week later, the government restored two of the four stations.

Regardless of the government’s rationale for cutting off TV broadcasting, it’s a disproportionate measure that interferes with the right to free expression, which includes the right to access information. This right is protected under the law.

One would think that this type of broad shutdown would be met with furious condemnation. But the rebukes have come mostly from media freedom veterans and organizations. In perhaps an indication of changes in foreign policy, the international community has taken a “balanced” diplomatic approach. The public wants vindication, as they have time and again raised concern over the media’s cosy relationship with the state. Should a media company’s purportedly dirty hands prevent us from defending its freedom? If we stay silent, could this TV switch-off lead to a full internet shutdown — despite the government’s pledge to keep the internet on?

For many years, Kenyans congregated in homes, entertainment venues, and other public spaces to watch the 7 o’clock news. In past eras, news content was largely from the executive point of view. In spite of the controls, people appreciated the news for its value in broadcasting information, regardless of the opinion it was clothed in. Fast forward to the present situation with Raila Odinga, leader of opposition, reading an oath before a crowd at Nairobi’s main public space, Uhuru Park.

Public curiosity about the Uhuru Park rally was high. Parts of the event were shared online and despite the fact that attention has shifted to the TV shutdown, analysis of the rally is ongoing. The government contends that by airing “an act of subversion,” the media is an accessory.

Public opinion is divided on the merit of Raila Odinga’s oath, with U.S. foreign policy reflecting support for the Kenyan government’s view that it is destabilizing for the nation. The three media houses that were shut down have taken cover under the constitutional guarantee of press independence.

Kenya’s Constitution protects speech online and off. The Constitution is relatively young, having been passed in 2010 with approval from 67% of Kenyan voters. It protects both the right to freedom of expression (art. 33), “which includes freedom to seek, receive or impart information or ideas,” and freedom of the media (art. 34), affirming people’s right to broadcast without interference or penalty based on the viewpoint or content transmitted. Both of these rights are subject to limited exceptions. On the policy side, Kenya is one of 30 governments in the Freedom Online Coalition, a partnership of states “working to advance internet freedom” that has spoken out against network disruptions.

A point of contention in the debate is whether the media has acted in good faith. Take for instance how and why the switch-off story became known in the public sphere: news editors were in a meeting with the government and they disagreed on coverage of the Uhuru Park event.

For its part, the public has warned the press about the dangers of an opaque relationship with the government. Examples range from the widely discussed media high tea at Statehouse in 2013, the creation of the government advertising agency, the running of government promotions during the 2017 election period, and the drafting of “conflict-sensitive” guidelines for the election period. Not to mention that the media framed the election as a binary between the ruling coalition, Jubilee, and the opposition forces under Raila Odinga, thereby contributing to polarization of the society. This is not to say that all of these policies were wholly wrong, but to point out that they were made with little or no public involvement, as if they were purely business and not public-interest decisions. These are not inclusive, multi-stakeholder processes.

Among urban populations, switching off four television stations does not appear to have had made much of an impact yet. This might be because there are alternative news sources, including the content from the four stations that is available online. But the problem with the switch-off is not just what it reveals about the relationship between the media and the public, but what it says about how our society is organized and how the rules are made.

In the past, Kenya went through a “one party era,” where the executive was in total control of policy, law, and practices, and everyone was expected to toe that line. Now we have a dispensation that envisages a plural society with a separation of powers. The executive should not be the last word on what information should be available in the public sphere and a dispute involving some content should not be resolved in a manner that affects whether the public can make choices in the marketplace of ideas.

For those who depend on “free-to-air” channels (which you can watch without paying for a subscription), the switch-off significantly limited their access to information. In one online discussion about the switch-off, a young Kenyan lamented that those without internet access were calling their friends and relatives in Nairobi to get a picture of the ongoings at Uhuru Park. A journalist from one of the switched-off stations discussed how his programs, which cover government technical and vocational institutions, were cancelled because of this action. Those who work under contract for content producers are also out of work during the switch-off.

Outside the broadcast media, businesses that provide access to information — for example, internet service providers (ISPs) — are undertaking economic, tech, and regulatory risk assessments, simulating scenarios in case they get a government directive. What happens if the switch-off targets online media? Will ISPs push back?

It may be that government had legitimate reasons for the action it took — that’s not clear — but even if it did, switching off four television stations goes too far for fixing the problem it’s trying to address. Restrictions like this on free expression should be targeted and necessary to achieve a legitimate aim. The message the switch-off has sent to the Kenyan people, allies, prospective investors, and the world, is that under this administration, one can never be sure of what will happen, even when a freedom is clearly spelled out in the Constitution.

This switch-off is therefore bad for our society. As Article 19, Amnesty International, and others stated, the blocking is “unacceptable” and curtails press freedom. We add that the switch-off fails to respect the values of openness and inclusivity that are essential to internet policy making, and threatens the new balance of powers in pluralist Kenya.

While we call upon the media to improve its relationship with the public, let us defend our freedom to access information and ideas, consider them, and judge for ourselves whether they are good for us.

Related posts:

Ugandan internet activist, legal team insists on constitutional interpretation

Ugandan internet activist, legal team insists on constitutional interpretation

“Closing Space for Civil Society and Media in East Africa: Forging a Collaborative Response”

“Closing Space for Civil Society and Media in East Africa: Forging a Collaborative Response”

Manipulating Social Media to Undermine Democracy

Manipulating Social Media to Undermine Democracy

Ruling party leaders want social media platforms indefinitely closed.

Ruling party leaders want social media platforms indefinitely closed.

You may like

-

More African governments are trying to control what’s being said on social media and blogs

-

Uganda ‘feels’ Tanzania’s tightening grip on social media

-

Access Now calls for global independent audit of Facebook data practices

-

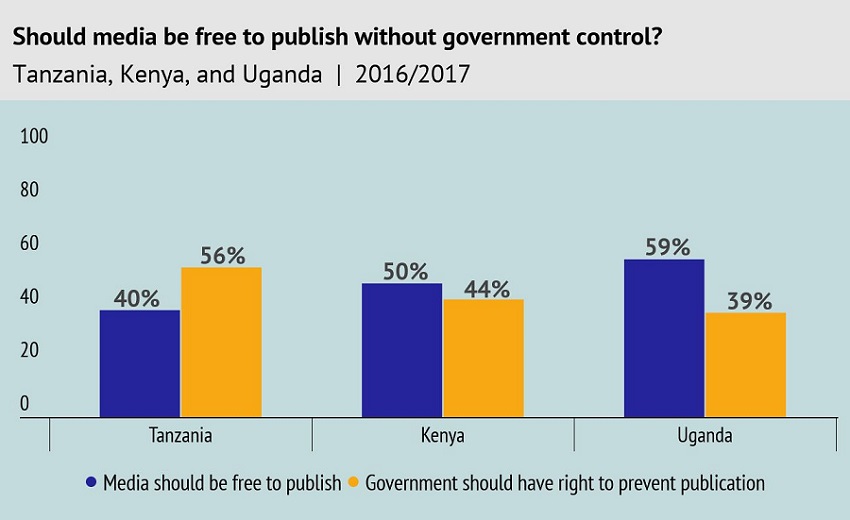

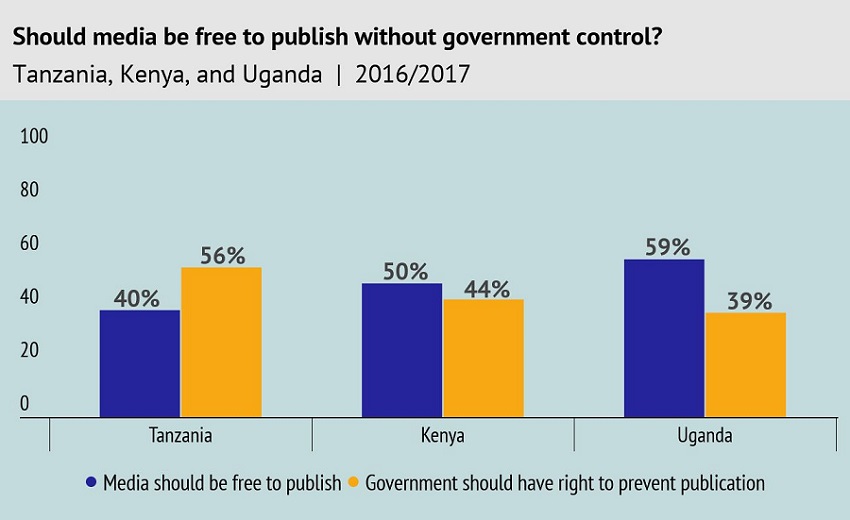

Do East Africans still want a free media?

-

Exclusive: Facebook Opens Up About False News

-

Privacy Vs Free Expression: Global News Media Implications Of The EU’S General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Published

3 days agoon

January 21, 2026

By Witness Radio team.

Uganda’s move to develop a national bamboo policy aims to boost environmental conservation and create green jobs, addressing the country’s urgent unemployment issues among the working class.

Bamboo is a critical tool in fighting climate change due to its rapid growth, high carbon sequestration capacity, and ability to produce 35% more oxygen than equivalent trees. As a fast-growing, renewable resource, it restores degraded land, provides sustainable materials that replace emission-intensive products like concrete, and offers a resilient, low-carbon bioenergy source.

Bamboo’s potential is outlined in the existing National Bamboo Strategy. Still, stakeholders stress that a formal policy involving entrepreneurs, farmers, and processors is essential to remove regulatory uncertainty and foster sector growth.

“The strategy is a good document, but it was developed largely through desk research. It did not fully involve entrepreneurs, farmers, and processors who are already working in the bamboo industry,” said Sjaak de Blois, chairman of Bamboo Uganda, encouraging stakeholders to see their role as vital.

The bamboo policy is currently at an early consultative stage, with no draft yet submitted to the cabinet or parliament. Recent consultations brought together representatives from eight government ministries, private-sector bamboo actors, and development partners to begin aligning the strategy with practical regulatory needs.

“What we have now is the starting point,” De Blois mentioned. “The next step is to take the strategy and make it more practical, more market-driven, and more Ugandan. The next step is to move from having a plan to adopting a policy.

Bamboo currently falls under several regulatory frameworks, with no single authority overseeing the sector. The policy push is being driven in part by Bamboo Uganda, a membership-based organization bringing together bamboo farmers and processors, among others. The organization aims to play a coordinating role similar to that historically played by the Uganda Coffee Development Authority in the coffee sector.

“If you want to make a sector meaningful for a country, you need coordination. Coffee became what it is because of an institution that aligned farmers, traders, exporters, and regulators. Bamboo needs the same kind of coordination.” He said.

The policy process is supported by the Belgian development agency, which is funding consultations and facilitating dialogue between the government and the private sector.

Industry players say the absence of clear regulations has constrained investment despite growing demand.

“At the moment, bamboo is everywhere and nowhere at the same time. As a farmer, you talk to forestry, as a charcoal producer, you talk to energy, as a builder, you talk to works. There is no single framework that enables the industry to function.” De Blois added.

Supporters of the policy argue that bamboo could play a significant role in environmental conservation. Bamboo grows rapidly, regenerates after harvesting, and can be harvested annually for decades, reducing pressure on natural forests.

According to Global Forest Watch (GFW), Uganda lost 1.2 million hectares of tree cover between 2001 and 2024, representing a 15% decline from the 2000 baseline. Bamboo has been identified as a key species for restoration.

“One acre of bamboo that is harvested sustainably can prevent the destruction of hundreds of acres of natural forest,” De Blois said. “If we get this right, bamboo can help reverse deforestation rather than contribute to it.”

Ms. Susan Kaikara, from the Ministry of Water and Environment, emphasized bamboo’s potential to drive Uganda’s green-growth agenda.

“Establishing a coherent national policy framework will strengthen coordination, inspire investment, and unlock bamboo’s full potential as a pillar of Uganda’s green economy,” she said.

Uganda’s charcoal market alone is estimated to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars annually, much of it supplied through unsustainable wood harvesting. Industry actors say certified bamboo charcoal plantations could offer a cleaner alternative.

“If they allow us to certify bamboo charcoal plantations, then we can get a trade license to compete or to work together with the existing market. We will reverse deforestation. We would enter an industry of about 500,000 hectares, creating smart, green jobs. We can digitalize them to make them attractive through bamboo agroforestry. So again, those things need a policy.” He adds.

Bamboo is also viewed as a climate-friendly crop due to its high capacity for carbon sequestration. Its rapid growth enables it to absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide, while its extensive root system improves soil structure and increases long-term carbon storage.

“When you look at carbon sequestration, bamboo offers several advantages. Residues from harvested bamboo can be converted into biochar, locking carbon into the soil for long periods. When you also see the sequestration per acre compared to many other trees, it is five or six times higher. So, we sequester a lot,” De Blois said

Stakeholders say that if the policy process progresses as planned, bamboo could emerge as one of Uganda’s key green growth sectors within the next decade.

“Policy making takes time. But what is important is that we have started the conversation with all the right ministries in the room. From here, it is about taking steady, practical steps.” He concluded.

Related posts:

As Uganda awaits the Energy Efficiency and Conservation law, plans to develop a five-year plan are underway.

As Uganda awaits the Energy Efficiency and Conservation law, plans to develop a five-year plan are underway.

REC25 & EXPO Ends with a call on Uganda to balance conservation and livelihood

REC25 & EXPO Ends with a call on Uganda to balance conservation and livelihood

Africa’s growth lies with smallholder farmers

Africa’s growth lies with smallholder farmers

Green Resources’ forestry projects are negatively impacting on local communities – donor

Green Resources’ forestry projects are negatively impacting on local communities – donor

WITNESS RADIO MILESTONES

A Global Report reveals that Development Banks’ Accountability Systems are failing communities.

Published

2 months agoon

December 4, 2025

By Witness Radio team.

For decades, development projects have been funded to address some of the World’s most pressing problems, including poverty, wildlife conservation, and climate change. However, what unfolds on the ground is sometimes the opposite of development. Instead of benefits, these projects have often harmed the very people they are supposed to support.

The effort to address such harm has led to the establishment of Independent Accountability Mechanisms (IAMs) by various development banks. Yet, communities affected by these projects often face betrayal by national court systems, leaving them feeling overlooked and vulnerable, emotions that underscore the urgent need for effective justice.

According to experts in development financing, since the early 1990s, development banks have sought to address and mitigate harm through IAMs—non-judicial grievance mechanisms that provide a direct avenue for impacted communities to raise concerns, engage with project implementers, and obtain remedies for the harm they have experienced.

The study, conducted by Accountability Counsel and titled Accountability in Action or Inaction? An Empirical Study of Remedy Delivery in Independent Accountability Mechanisms shows that while IAMs exist, their relevance has fallen short, underscoring the urgent need for reform to restore community trust and hope.

In compiling the report, researchers reviewed 2,270 complaints across 16 IAMs and conducted 45 interviews covering 25 cases globally.

The report reveals a persistent gap between the promise of remedies and their realization, highlighting that only 15% of closed complaints led to commitments, and just 10% achieved full completion, underscoring the urgent need for effective remedies for communities.

The findings highlight ongoing challenges, including inadequate implementation, limited monitoring, and persistent power imbalances, which continue to block communities from accessing meaningful remedies and demand immediate reform.

“The consequences of these institutional gaps are severe. As these cases show, institutional silence can exacerbate risk, while meaningful intervention can help de-escalate it.” The Report adds.

Uganda is among the countries where communities have sought justice using these accountability mechanisms. Between 2006 and 2010, communities in one of the districts of Uganda were brutally evicted by the UK-based Company, which was growing trees in the area.

The company was formerly an investee of the Agri-Vie Agribusiness Fund, a private equity fund supported by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private sector arm of the World Bank Group. The community filed a Complaint with the IFC’s accountability mechanism, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO).

“We complained to this body in 2011, hoping for justice, but over 15 years later our people are still struggling, living miserably, some without homes,” a community land and environmental defender told the Witness Radio team.

According to the affected residents, the CAO process did not lead to success or meaningful compensation, as they had hoped.

Between 2013 and 2014, the communities, with support from the CAO, signed a final agreement with the Company to address the harm. Among other commitments, this included resettlement of the affected communities.

In its 28-page report published in 2015 titled: A Story of Community-Company Dispute Resolution in Uganda, the CAO wrote,” With the agreements concluded, implementation is gathering pace. As agreed, the company has begun extending development assistance to both cooperatives, and the process of restoring and enhancing livelihoods has commenced.

The first step taken by both cooperatives was to acquire land. In late 2013, the Mubende Cooperative bought 500 acres of ‘fertile agricultural land’ in the Mubende district. Their vision was to allocate a certain percentage of the land for resettlement, with the remainder utilized for farming projects.

Reports from the ground indicate that communities remain dissatisfied with the process, claiming it failed to address their concerns fully and highlighting the urgent need for more effective remedy systems.

“When you say that people are well, it is really a total lie. Many people were never compensated or resettled. Even those who got a portion of land say they have never seen a fertile land—I have never seen it, because people are living or cultivating on rocky, infertile lands,” the defender further revealed.

The struggle faced by the Ugandan community is not unique. Their experience mirrors what the Accountability Counsel report identifies worldwide. Despite registering more than 2000 complaints by communities harmed by bank-financed projects globally, there has been no comprehensive system-wide analysis of whether and how often these mechanisms deliver meaningful remedies, defined as tangible, material outcomes that repair harm and improve lives.

In addition to the slow success of such IAMs, the report notes that, across interviews covering 25 complaints, 84% referenced retaliation, violence, or threats of violence-an alarming indicator of the risks faced by communities seeking justice, demanding immediate attention and action.

“Government officials and company representatives were frequently implicated in efforts to suppress dissent. This not only reduces the likelihood of achieving a substantial remedy, but also suppresses the willingness of community members to speak honestly and openly about Complaint outcomes.” The report further adds,

Further, it reveals that communities described a range of retaliatory tactics, including physical clashes, arrests, detentions, fatalities, intimidation and harassment, death threats, and anonymous warning letters, among others.

“Remedy must be reimagined not as a peripheral concern but as a core responsibility of development institutions. It must be adequately resourced, independently monitored, and centered around the needs and voices of affected people,” the report adds.

The report recommends that development banks and IAMs establish a Remedy Framework with clear standards to ensure remedies are timely, adequate, and community-centered, and to encourage stakeholders to prioritize systemic reform for better justice outcomes.

The report also urges development banks and their accountability mechanisms to make remedies a foundational element of responsible finance. Adopting institutional frameworks that prioritize redress, empowering IAMs to oversee and enforce commitments, and incorporating the outcomes of IAM processes into project evaluations and institutional learning.

Related posts:

Banks have given almost $7tn to fossil fuel firms since Paris deal, report reveals

Banks have given almost $7tn to fossil fuel firms since Paris deal, report reveals

Opinion: USAID needs an independent accountability office to improve development outcomes

Opinion: USAID needs an independent accountability office to improve development outcomes

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

Oxfam Report 2011: When Indigenous communities named Rwanda nationals by investor to run away from corporate accountability

Oxfam Report 2011: When Indigenous communities named Rwanda nationals by investor to run away from corporate accountability

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Young activists fight to be heard as officials push forward on devastating project: ‘It is corporate greed’

Published

5 months agoon

August 27, 2025

“We refuse to inherit a damaged planet and devastated communities.”

Youth climate activists in Uganda protesting the East African Crude Oil Pipeline, or EACOP, are frustrated with the government’s response to their demonstration as the years-long project moves forward.

According to the country’s Daily Monitor, youth activists organized with End Fossil Occupy Uganda took to the streets of Kampala in early August to protest EACOP. The pipeline, under construction since about 2017 and now 62 percent complete, is set to transport crude oil from Uganda’s Tilenga and Kingfisher fields through Tanzania to the Indian Ocean port of Tanga by 2026.

Activists noted the devastating toll, with group spokesperson Felix Musinguzi saying that already around 13,000 people “have lost their land with unfair compensation” and estimating that around 90,000 more in Uganda and Tanzania could be affected. End Fossil Occupy Uganda has also warned of risks to vital water sources, including Lake Victoria, which it says 40 million people rely on.

The group has been calling on financial institutions to withdraw funding for the project. Following a demonstration at Stanbic Bank earlier in the month, 12 activists were arrested, according to the Daily Monitor.

Some protesters were seen holding signs reading “Every loan to big oil is a debt to our children” and “It’s not economic development; it is corporate greed.”

Meanwhile, the regional newspaper says the government has described the activist efforts as driven by foreign actors who mean to subvert economic progress.

EACOP’s site notes that its shareholders include French multinational TotalEnergies — owning 62 percent of the company’s shares — Uganda National Oil Company, Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation, and China National Offshore Oil Corporation.

The wave of young people taking action against EACOP could be seen as a sign of growing public frustration over infrastructural projects that promise economic gain while bringing harm to local communities and ecosystems. Activists say residents face costly threats from pipeline development, such as forced displacement and the loss of livelihoods.

Environmental hazards to Lake Victoria could also disrupt water supplies and food systems, bringing the potential for both financial and health impacts. Just 10 years ago, an oil spill in Kenya caused a humanitarian crisis. The Kenya Pipeline Company reportedly attributed the spill to pipeline corrosion, which led to contamination of the Thange River and severe illness.

The EACOP project has already locked the region into close to a decade of development, and concerns about the pipeline and continued investments in carbon-intensive systems go back just as long. Youth activists, as well as concerned citizens of all ages, say efforts to move toward climate resilience can’t wait. “As young people, we refuse to inherit a damaged planet and devastated communities,” Musinguzi said, per the Monitor.

Source: The Cool Down

Related posts:

Put people above profits – Climate Activists urge Total to defund EACOP

Put people above profits – Climate Activists urge Total to defund EACOP

EACOP: The number of activists arrested for opposing the project is already soaring in just a few months of 2025

EACOP: The number of activists arrested for opposing the project is already soaring in just a few months of 2025

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

The East African Court of Justice fixes the ruling date for a petition challenging the EACOP project.

The East African Court of Justice fixes the ruling date for a petition challenging the EACOP project.

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Swedish pension fund drops TotalEnergies amid rising EACOP risks

Land tenure security as an electoral issue: Museveni warns Kayunga land grabbers, reaffirms protection of sitting tenants.

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoWill Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days agoUganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoCOP30 : a further step towards a Just Transition in Africa

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoUnited States withdraws from core United Nations climate institutions

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK18 hours ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK18 hours agoWomen environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

-

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks agoViolations against Kenya’s indigenous Ogiek condemned yet again by African Court

-

FARM NEWS1 day ago

FARM NEWS1 day ago200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly