On 2 November 2021, at COP26 in Glasgow, more than 100 governments signed on to the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forest and Land Use. Boris Johnson, UK Prime Minister, described it as a “landmark agreement to protect and restore the earth’s forests”. Johnson also called the pledges under the agreement “unprecedented”.

Colombia’s President Iván Duque also called the Declaration a “landmark commitment” and said that, “Never before have so many leaders, from all regions, representing all types of forests, joined forces in this way.”

Michelle Passero of The Nature Conservancy told Al Jazeera that the Declaration was a “terrific start”.

UN forest declarations: A short history

The reality is that this is far from the first UN forest declaration.

In 1992, at the UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio, governments agreed a “Non-legally binding authoritative statement of principles for a global consensus on the management, conservation and sustainable development of all types of forests”.

Following on from UNCED, in June 1995, the UN set up “an ad hoc open-ended Intergovernmental Panel on Forests”.

In 2000, the Economic and Social Council of the UN (ECOSOC) replaced the Intergovernmental Panel on Forests with the UN Forum on Forests and set up the International Arrangement on Forests, which has five components: the UN Forum on Forests (UNFF) and its Member States; the UNFF Secretariat; the Collaborative Partnership on Forests (CPF); the UNFF Global Forest Financing Facilitation Network (GFFFN); and the UNFF Trust Fund.

The Collaborative Partnership on Forests was set up in 2001 and consists of the following organisations:

In January 2020, the Collaborative Partnership on Forests put out a Strategic Vision towards 2030, which includes the following “Vision Statement”:

‘By 2030 all types of forests and forest landscapes are sustainably managed, their multiple values are fully recognized, the potential of forests and their goods and services is fully unlocked, and the Global Forest Goals, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and other global forest-related goals, targets and commitments are achieved.’

The UN Forum on Forests is supposed to promote “the management, conservation and sustainable development of all types of forests and to strengthen long-term political commitment to this end”.

In fact, the UN Forum on Forests has achieved little or nothing apart from meeting every year. In December 2007, the UN General Assembly adopted a “Non-legally binding instrument on all types of forests”.

In January 2017, the UN Forum on Forests agreed to create the UN Strategic Plan for Forests. It was adopted by the UN General Assembly in April 2017. The Strategic Plan sets out six “forest goals”. Goal number one is to:

‘Reverse the loss of forest cover worldwide through sustainable forest management, including protection, restoration, afforestation and reforestation, and increase efforts to prevent forest degradation and contribute to the global effort of addressing climate change.’

Meanwhile, in 2014, at the UN Climate Summit, governments signed on to a “non-legally binding political declaration” called the New York Declaration on Forests. This aimed to reduce deforestation in half by 2020 to end it by 2030.

A five year assessment report put out in 2019 found that,

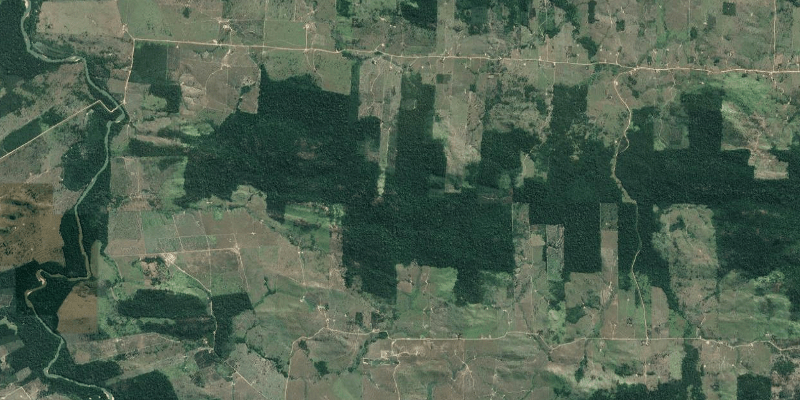

‘Instead of slowing down, tropical deforestation has continued at an unsustainable pace since the adoption of the NYDF. Since 2014, the world has lost an area of tree cover the size of the United Kingdom every year.’

And then there’s REDD

REDD was introduced at the COP11 in Montreal in 2005. REDD was discussed at great length in a series of UN climate meetings. Between 2007 and 2013, the UNFCCC adopted 13 decisions on REDD.

But REDD has completely failed to address deforestation. Even worse, it’s a carbon trading mechanism, meaning that even if emissions from deforestation were reduced, any reduction would be cancelled out by continued emissions from burning fossil fuels.

In 2020, the loss of primary old-growth tropical forest increased by 12% compared to 2019. This happened in a year that the global economy contracted by at least 3%.

Funding to save the forests?

Under the Glasgow Forest Declaration, 12 countries promised to provide US$12 billion between 2021 and 2025 to restore degraded land and to tackle forest fires. Much of this public funding is already committed, and significant amount will no doubt be poured into the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility. Despite more than US$1 billion funding the FCPF has failed to save a single hectare of forest.

A further US$7.2 billion will come from private sector investors including Aviva, Schroders, and AXA. But this money will be spent on buying carbon credits, allowing Big Polluters to continue polluting, and thus cancelling out any reduction in emissions from reduced deforestation.

Souparna Lahiri of the Global Forest Coalition isn’t impressed by the idea of pouring money at the problem of deforestation. In a statement put out by the Climate Land Ambition and Rights Alliance (CLARA) Lahiri says:

‘This Declaration is one of those oft repeated attempts to make us believe that deforestation can be stopped and forest can be conserved by pushing billions of dollars into the land and territories of the Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities. More money means more land grab, violation of the rights of the IPLCs [Indigenous Peoples and local communities] and women, and more corporate incursion into forests. Time has come to let these political leaders know that any effort towards halting deforestation and forest conservation should begin with recognising the rights of the IPLCs and women and ensuring tenurial and collective rights and governance over and access to forests for IPLCs, and particularly women. Without these structural transformations, these Declarations will always sound hollow, and result in not only not achieving their objectives but leave behind scarred forests, biodiversity and communities.’

Greenpeace criticised the Glasgow Forest Declaration as “a green light for another decade of forest destruction”. In a press release, Carolina Pasquali of Greenpeace Brazil says,

‘There’s a very good reason Bolsonaro felt comfortable signing on to this new deal. It allows another decade of forest destruction and isn’t binding. Meanwhile the Amazon is already on the brink and can’t survive years more deforestation.’

Original source: redd-monitor.org

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK18 hours ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK18 hours ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

FARM NEWS1 day ago

FARM NEWS1 day ago