WITNESS RADIO MILESTONES

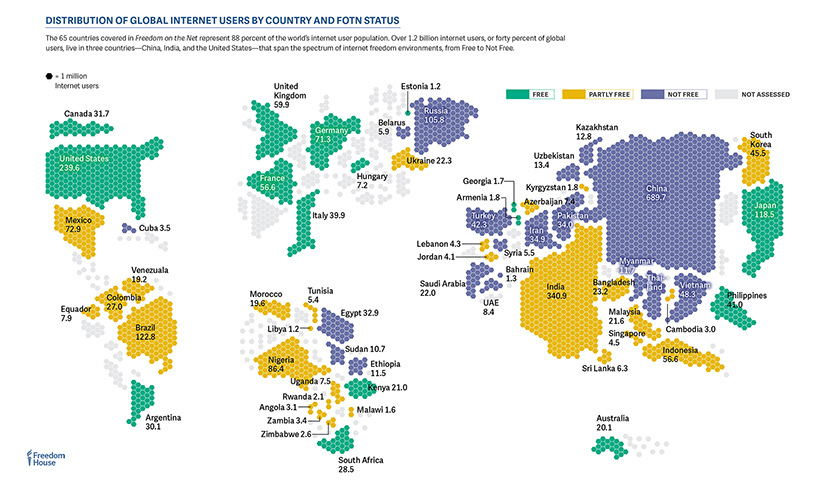

Freedom on the Net 2016

Published

9 years agoon

- Internet freedom around the world declined in 2016 for the sixth consecutive year.

- Two-thirds of all internet users – 67 percent – live in countries where criticism of the government, military, or ruling family are subject to censorship.

- Social media users face unprecedented penalties, as authorities in 38 countries made arrests based on social media posts over the past year. Globally, 27 percent of all internet users live in countries where people have been arrested for publishing, sharing, or merely “liking” content on Facebook.

- Governments are increasingly going after messaging apps like WhatsApp and Telegram, which can spread information quickly and securely.

by Sanja Kelly, Mai Truong, Adrian Shahbaz, and Madeline Earp

Internet freedom has declined for the sixth consecutive year, with more governments than ever before targeting social media and communication apps as a means of halting the rapid dissemination of information, particularly during anti-government protests.

Public-facing social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter have been subject to growing censorship for several years, but in a new trend, governments increasingly target voice communication and messaging apps such as WhatsApp and Telegram. These services are able to spread information and connect users quickly and securely, making it more difficult for authorities to control the information landscape or conduct surveillance.

Freedom on the Net 2016 Overall Scores

Freedom on the Net Score: 0=Most Free, 100=Less Free

Internet freedom has declined for the sixth consecutive year, with more governments than ever before targeting social media and communication apps as a means of halting the rapid dissemination of information, particularly during anti-government protests.

The increased controls show the importance of social media and online communication for advancing political freedom and social justice. It is no coincidence that the tools at the center of the current crackdown have been widely used to hold governments accountable and facilitate uncensored conversations. Authorities in several countries have even resorted to shutting down all internet access at politically contentious times, solely to prevent users from disseminating information through social media and communication apps, with untold social, commercial, and humanitarian consequences.

Some communication apps face restrictions due to their encryption features, which make it extremely difficult for authorities to obtain user data, even for the legitimate purposes of law enforcement and national security. Online voice and video calling apps like Skype have also come under pressure for more mundane reasons. They are now restricted in several countries to protect the revenue of national telecommunications firms, as users were turning to the new services instead of making calls through fixed-line or mobile telephony.

Other key trends

Social media users face unprecedented penalties: In addition to restricting access to social media and communication apps, state authorities more frequently imprison users for their posts and the content of their messages, creating a chilling effect among others who write on controversial topics. Users in some countries were put behind bars for simply “liking” offending material on Facebook, or for not denouncing critical messages sent to them by others. Offenses that led to arrests ranged from mocking the king’s pet dog in Thailand to “spreading atheism” in Saudi Arabia. The number of countries where such arrests occur has increased by over 50 percent since 2013.

Governments censor more diverse content: Governments have expanded censorship to cover a growing diversity of topics and online activities. Sites and pages through which people initiate digital petitions or calls for protests were censored in more countries than before, as were websites and online news outlets that promote the views of political opposition groups. Content and websites dealing with LGBTI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex) issues were also increasingly blocked or taken down on moral grounds. Censorship of images—as opposed to the written word—has intensified, likely due to the ease with which users can now share them, and the fact that they often serve as compelling evidence of official wrongdoing.

Security measures threaten free speech and privacy: In an effort to boost their national security and law enforcement powers, a number of governments have passed new laws that limit privacy and authorize broad surveillance. This trend was present in both democratic and nondemocratic countries, and often led to political debates about the extent to which governments should have backdoor access to encrypted communications. The most worrisome examples, however, were observed in authoritarian countries, where governments used antiterrorism laws to prosecute users for simply writing about democracy, religion, or human rights.

Online activism reaches new heights: The internet remained a key tool in the fight for better governance, human rights, and transparency. In over two-thirds of the countries in this study, internet-based activism has led to some sort of tangible outcome, from the defeat of a restrictive legislative proposal to the exposure of corruption through citizen journalism. During the year, for example, internet freedom activists in Nigeria helped thwart a bill that would have limited social media activity, while a WhatsApp group in Syria helped save innocent lives by warning civilians of impending air raids.

Tracking the global decline

Freedom on the Net is a comprehensive study of internet freedom in 65 countries around the globe, covering 88 percent of the world’s internet users. It tracks improvements and declines in governments’ policies and practices each year, and the countries included in the study are selected to represent diverse geographical regions and types of polity. This report, the seventh in its series, focuses on developments that occurred between June 2015 and May 2016, although some more recent events are included in individual country narratives. More than 70 researchers, nearly all based in the countries they analyzed, contributed to the project by examining laws and practices relevant to the internet, testing the accessibility of select websites, and interviewing a wide range of sources.

Of the 65 countries assessed, 34 have been on a negative trajectory since June 2015. The steepest declines were in Uganda, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Ecuador, and Libya. In Uganda, the government made a concerted effort to restrict internet freedom in the run-up to the presidential election and inauguration in the first half of 2016, blocking social media platforms and communication services such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp for several days. In Bangladesh, Islamist extremists claimed responsibility for the murders of a blogger and the founder of an LGBTI magazine with a community of online supporters. And Cambodia passed an overly broad telecommunications law that put the industry under government control, to the detriment of service providers and user privacy. Separately, Cambodian police arrested several people for their Facebook posts, including one about a border dispute with Vietnam.

China was the year’s worst abuser of internet freedom. The Chinese government’s crackdown on free expression under President Xi Jinping’s “information security” policy is taking its toll on the digital activists who have traditionally fought back against censorship and surveillance. Dozens of prosecutions related to online expression have increased self-censorship, as have legal restrictions introduced in 2015. A criminal law amendment added seven-year prison terms for spreading rumors on social media (a charge often used against those who criticize the authorities), while some users belonging to minority religious groups were imprisoned simply for watching religious videos on their mobile phones. The London-based magazine Economist and the Hong Kong–based South China Morning Post were newly blocked in mainland China, as were articles and commentaries about sensitive events including a deadly chemical blast in Tianjin in 2015.

Turkey and Brazil were downgraded in their internet freedom status. In Brazil, which slipped from Free to Partly Free, courts imposed temporary blocks on WhatsApp for its failure to turn over user data in criminal investigations, showing little respect for the principles of proportionality and necessity. Moreover, at least two bloggers were killed after reporting on local corruption. Turkey, whose internet freedom environment has been deteriorating for a number of years, dropped into the Not Free category amid multiple blockings of social media platforms and prosecutions of users, most often for offenses related to criticism of the authorities or religion. These restrictions continued to escalate following the failed coup in July 2016, in spite of the crucial role that social media and communication apps—most notably FaceTime—played in mobilizing citizens against the coup.

Just 14 countries registered overall improvements. In most cases, their gains were quite modest. Users in Zambia faced fewer restrictions on online content compared with the previous few years, when at least two critical news outlets were blocked. South Africa registered an improvement due to the success of online activists in using the internet to promote societal change and diversifying online content, rather than any positive government actions. Digital activism also flourished in Sri Lanka as censorship and rights violations continued to decline under President Maithripala Sirisena’s administration. And the United States registered a slight improvement to reflect the passage of the USA Freedom Act, which puts some limits on bulk collection of telecommunications metadata and establishes several other privacy protections.

Major developments

Social Media and Communication Tools Under Assault

In the past year, social media platforms, communication apps, and their users faced greater threats than ever before in an apparent backlash against growing citizen engagement, particularly during politically sensitive times. Of the 65 countries assessed, governments in 24 impeded access to social media and communication tools, up from 15 the previous year. Governments in 15 countries temporarily shut down access to the entire internet or mobile phone networks, sometimes solely to prevent users from disseminating information through social media. Meanwhile, the crackdown on users for their activities on social media or messaging apps reached new heights as arrests and punishments intensified.

New restrictions on messaging apps and internet-based calls

In a new development, the most routinely targeted tools this year were instant messaging and calling platforms, with restrictions often imposed during times of protests or due to national security concerns. Governments singled out these apps for blocking due to two important features: encryption, which protects the content of users’ communications from interception, and text or audiovisual calling functions, which have eroded the business model and profit margins of traditional telecommunications companies.

Whatever the justification, restrictions on social media and internet-based communication tools threaten to infringe on users’ fundamental right to access the internet. In a landmark resolution passed in July 2016, the UN Human Rights Council condemned state-sponsored disruptions to internet access and the free flow of information online.

WhatsApp faced the most restrictions, with 12 out of 65 countries blocking the entire service or disabling certain features, affecting millions of its one billion users worldwide. Telegram, Viber, Facebook Messenger, LINE, IMO, and Google Hangouts were also regularly blocked. Ten countries restricted access to platforms that enable voice and video calling over the internet, such as Skype and FaceTime.

Nearly ubiquitous among internet and mobile phone users, these communication platforms have become essential to the way we connect with the world. Incidents of blocking have had far-reaching effects, preventing family members from checking in during a crisis, activists from documenting police abuses during a protest, and individuals from communicating affordably with social and professional contacts abroad.

While all users are adversely affected by restrictions, the harm is often disproportionately felt by marginalized communities and minority groups, who are more likely to be cut off from critical information sources and the ability to advocate for their rights. In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), for example, where migrant workers and other noncitizens make up 88 percent of the population, blocks on communication tools have made it difficult for these individuals to organize or seek support from their home countries.

App blocking aimed at protests, expressions of dissent

Authoritarian regimes most frequently restricted communication apps to prevent or quell antigovernment protests, as they have become indispensable for sharing information on demonstrations and organizing participants in real time. In Ethiopia, ongoing protests that began in November 2015 in response to the government’s marginalization of the Oromo people have been met with periodic blocks on services including WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, and Twitter. In Bahrain, Telegram was blocked for several days around the anniversary of the February 14, 2011, “Day of Rage” protests, likely to quash any plans for renewed demonstrations.

In Bangladesh, the authorities ordered the blocking of platforms including Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, and Viber to prevent potential protests following a Supreme Court ruling in November that upheld death sentences for two political leaders convicted of war crimes. The longest block lasted 22 days. In Uganda, officials directed internet service providers to block WhatsApp, Facebook, and Twitter for several days during the presidential election period in February 2016 and again in the run-up to the reelected incumbent’s inauguration in May. In both instances, the unprecedented blocking worked to silence citizens’ discontent with the president’s 30-year grip on power and their efforts to report on the ruling party’s notorious electoral intimidation tactics.

New security and encryption features also trigger blocking

Governments increasingly imposed restrictions on internet-based messaging and calling services due to their strong privacy and security features, which have attracted many users amid growing concerns about surveillance worldwide.

In many countries, individuals are using messaging apps as private social networks where they can enjoy greater freedom of expression than on more established, public-facing social networks such as Facebook and Twitter. New messaging and calling apps also provide greater anonymity than conventional voice and SMS services that can be tracked due to SIM-card registration requirements, and several offer end-to-end encryption that prevents wiretapping and interception.

Activists and human rights defenders in repressive countries protect their communications by convening on WhatsApp, Viber, and Telegram to share sensitive information, conduct advocacy campaigns, or organize protests. Journalists in Turkey, for example, have established new distribution networks for their reporting via group channels on WhatsApp to avert censorship.

The same security features that appeal to users of the new platforms have brought them into conflict with governments in both democratic and authoritarian countries. In Brazil in 2015 and 2016, regional courts ordered a block on WhatsApp three times after it failed to turn over encrypted communications to local authorities during criminal investigations. On all three occasions, WhatsApp’s parent company, Facebook, insisted that it did not have access to the information in question, since WhatsApp does not store the content of users’ communications. Nevertheless, the judges chose to penalize not just the company, but also Brazil’s 100 million WhatsApp users.

Authoritarian regimes targeted Telegram for its “secret chat” mode, which allows messages to self-delete after a period of time. The platform was blocked in China after the authorities learned of its popularity among human rights lawyers, joining a long list of other international communication apps that are unavailable to Chinese users. State-run news outlets in the country accused Telegram of aiding activists in “attacks on the [Communist] Party and government.” Iran also targeted Telegram, blocking it for a week in October 2015 when it refused to aid officials’ surveillance and censorship efforts. In May 2016, Iran’s Supreme Council on Cyberspace ordered Telegram to host all data on Iranian users inside the country or face blocking.

Market threats to national telecoms lead to backlash

Internet-based messaging and calling platforms faced increasing restrictions from governments seeking to protect their countries’ major state-owned or private telecommunications companies. Given the rising popularity of new communication services over the past decade, telecoms in some markets have become concerned about the future economic viability of their traditional text and voice services, particularly when the new competitors are not subject to the same regulatory obligations and fees.

Typically free to download, messaging platforms such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and Facebook Messenger have proliferated in emerging markets, where the advent of low-cost, internet-enabled mobile devices and smartphones have made sending messages, photos, and even videos via online tools much more affordable than traditional SMS, for which telecom carriers charge a variable rate per message. Indeed, app-based mobile messaging has surpassed SMS texting worldwide since at least 2013.

Similarly, Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) and internet-based video calling services such as Skype, Google Hangouts, and Apple’s FaceTime have significantly reduced the cost of real-time audio and visual communication for users, resulting in the decreased use of traditional phone services that charge by the minute. Though telecom companies still profit from the data used by internet-based platforms, continual improvements in network infrastructure have only made data plans cheaper, threatening to leave traditional voice and SMS services further behind.

One of the first market-related restrictions on internet-based communication services was imposed by the American telecommunications company AT&T in 2007, when it partnered with Apple to become the sole mobile provider for the first iPhone and subsequently banned VoIP applications that could make calls using a wireless data connection. Google’s Voice app was consequently rejected by the iPhone’s app store, and Skype developed a version of its platform that only allowed iPhone users to make calls when connected to a Wi-Fi network. Under pressure from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), AT&T changed course in 2009, setting a positive precedent and providing users with more freedom to choose from a suite of services based on quality and affordability.

In the past year, restrictions to protect market interests escalated most prominently in the Middle East and North Africa. The UAE had been an early mover, requiring VoIP services to obtain a license to operate as a telecom provider and subsequently blocking both the voice and video calling features of Skype, WhatsApp, and Facebook Messenger in 2014, in an effort to protect the profits of state-owned telecom companies. Most recently, Snapchat’s calling function was disabled in April 2016. While circumvention tools such as virtual private networks (VPNs) were widely used to bypass the blocks, the government cracked down in July 2016, adopting amendments to the Cybercrime Law that penalize the “illegal” use of VPNs with temporary imprisonment, fines of between US$136,000 and US$545,000, or both.

Morocco’s telecommunications regulator issued a directive in January 2016 that suspended all internet calling services over mobile networks, citing previously unenforced licensing requirements under the 2004 telecommunications law. The order seemed heavily influenced by the UAE’s Etisalat, which purchased a majority stake in Maroc Telecom, the country’s largest operator, in 2014. In Egypt, where long-distance VoIP calls on Skype have been blocked since 2010, voice calling features on WhatsApp and Viber have reportedly been inaccessible since October 2015. The calling functions of popular platforms were also disabled in Saudi Arabia, while Apple has been forced to sell its iPhone in the kingdom without the built-in FaceTime app.

Pressure to regulate mobile communication services in the past year threatened to impede access to such platforms in other regions, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, where mobile internet use has been growing rapidly. In Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, private telecommunications companies lobbied governments to regulate internet-based messaging and voice calling platforms such as Skype and WhatsApp, citing concerns over their profits. Meanwhile, Ethiopia’s single telecommunications provider, state-owned EthioTelecom, announced plans in April 2016 to introduce a new pricing scheme for mobile users of popular communication applications. Companies in the European Union (EU) pushed EU officials throughout 2016 to regulate new communication services, calling for a “level playing field” that subjects messaging and calling platforms to the same regulatory framework, licensing fees, and law enforcement access requirements as traditional telecoms.

Social media users face unprecedented penalties

While many governments attempted to restrict access to social media and communication platforms, far more turned to traditional law enforcement methods to punish and deter users. Since June 2015, police in a remarkable 38 countries arrested individuals for their activities on social media[ME6] , compared with 21 countries where people were arrested for content published on news sites or blogs. The rising penetration of social networks in repressive societies has enabled discussion and information sharing on issues that governments deem sensitive, resulting in arrests of journalists, politicians, activists, and ordinary citizens who may not be aware that they are crossing redlines.

A Turkish man was handed a one-year suspended sentence for this meme juxtaposing President Reçep Tayyip Erdogan and a character from the Lord of the Rings films. In determining whether or not the image insulted the president, the judge assembled a panel of film experts. Another user is facing up to two years in prison for reposting the same memes.

Dramatic sentences for social media ‘crimes’

Social media users were prosecuted for a range of alleged crimes during the coverage period. Some supposed offenses were quite petty, illustrating both the sensitivity of some regimes and the broad discretion given to police and prosecutors under applicable laws. Lebanon’s bureau of cybercrimes interrogated a Facebook user for criticizing a Lebanese singer, while soldiers in the UAE were arrested for disrespecting the army after they shared a video of themselves recreating a popular dance craze in their uniforms.

While severe punishments for online speech are not new, their application to social media activities that many people engage in daily was a cause for serious concern. In February 2016, a Saudi court sentenced an individual to 10 years in prison and 2,000 lashes for allegedly spreading atheism in 600 tweets. In the harshest examples of the coverage period, military courts in Thailand issued 60- and 56-year sentences in separate cases involving Facebook posts that were deemed critical of the monarchy in August 2015, though they were reduced to 30 and 28 years after the defendants pleaded guilty. While sentences like these may not cause people to stop using social media entirely, they are likely to encourage self-censorship on sensitive topics, robbing the technology of its potential for galvanizing social and political change.

Many detentions were justified under criminal laws penalizing defamation or insult, but they often aimed to suppress information in the public interest. In Morocco, YouTube footage of a man lifting asphalt barehanded from a local road led to his arrest for allegedly defaming the official responsible for the poor construction.

Users punished for their connections and readership

One goal of social media is to allow users to share content with a wide circle of connections. Police in some countries seem determined to undermine that goal, specifically pursuing individuals whose content goes viral. In Zimbabwe, Pastor Evan Mawarire was arrested in July 2016 after his YouTube videos criticizing the country’s leadership sparked the #ThisFlag social media campaign and inspired nationwide protests. Elsewhere, charges often multiplied as content was passed along: In November 2015, 17 people in Hungary were charged with defamation for sharing a Facebook post that questioned the legitimacy of the mayor of Siófok’s financial dealings.

In a disturbing development, defendants whose content failed to spread widely were nevertheless punished as a warning to others. In Russia, mechanical engineer Andrey Bubeyev was sentenced to two years in prison in May 2016 for reposting material that identified the Russian-occupied Crimean Peninsula as part of Ukraine on the social network VKontakte. He shared the information with just 12 contacts.

Authorities in other cases scoured social media for a pretext to charge specific individuals, or were so intent on suppressing certain content that identifying the correct defendant was of secondary importance. In Ethiopia, charges against an opposition politician and student protesters principally cited evidence gleaned from social media. Pseudonymous accounts offered limited protection and raised the risk of mistaken identity. A man in Uganda was charged on suspicion of operating the popular Facebook page Tom Voltaire Okwalinga, but he denied being responsible for the page, which frequently accused senior leaders of corruption and incompetence. Some people were held responsible for posts clearly made by others. At least three criminal charges were filed in India against the administrators of WhatsApp groups based on offensive or antireligious comments shared by other group members.

A number of users were apparently targeted only to punish their associates. In Thailand, Patnaree Chankij, the mother of an activist who opposes Thailand’s military government, was charged with insulting the monarchy based on a private, one-word acknowledgement she sent in reply to a Facebook Messenger post from her son’s friend; police said she failed to criticize or take action against the antiroyalist sentiment in the post, instead replying “yes” or “I see.” Patnaree told journalists that the charge was in reprisal for her son’s activities. In China, police detained the local relatives of at least three overseas journalists and bloggers who produce online content that the Chinese government perceives as critical.

Governments censor more diverse content

This year featured new trends in the type of content that attracted official censorship. Posts related to the LGBTI community, political opposition, digital activism, and satire resulted in blocking, takedowns, or arrests for the first time in many settings. Authorities also demonstrated an increasing wariness of the power of images on today’s internet.

A longer roster of forbidden topics

Related posts:

Internet shutdowns cost countries $2.4 billion last year

Internet shutdowns cost countries $2.4 billion last year

Ugandan internet activist, legal team insists on constitutional interpretation

Ugandan internet activist, legal team insists on constitutional interpretation

Three challenges for the web, according to its inventor

Three challenges for the web, according to its inventor

Uganda declines on Internet freedoms Global Rankings – 2016 Freedom House Internet report

Uganda declines on Internet freedoms Global Rankings – 2016 Freedom House Internet report

You may like

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Published

2 weeks agoon

January 21, 2026

By Witness Radio team.

Uganda’s move to develop a national bamboo policy aims to boost environmental conservation and create green jobs, addressing the country’s urgent unemployment issues among the working class.

Bamboo is a critical tool in fighting climate change due to its rapid growth, high carbon sequestration capacity, and ability to produce 35% more oxygen than equivalent trees. As a fast-growing, renewable resource, it restores degraded land, provides sustainable materials that replace emission-intensive products like concrete, and offers a resilient, low-carbon bioenergy source.

Bamboo’s potential is outlined in the existing National Bamboo Strategy. Still, stakeholders stress that a formal policy involving entrepreneurs, farmers, and processors is essential to remove regulatory uncertainty and foster sector growth.

“The strategy is a good document, but it was developed largely through desk research. It did not fully involve entrepreneurs, farmers, and processors who are already working in the bamboo industry,” said Sjaak de Blois, chairman of Bamboo Uganda, encouraging stakeholders to see their role as vital.

The bamboo policy is currently at an early consultative stage, with no draft yet submitted to the cabinet or parliament. Recent consultations brought together representatives from eight government ministries, private-sector bamboo actors, and development partners to begin aligning the strategy with practical regulatory needs.

“What we have now is the starting point,” De Blois mentioned. “The next step is to take the strategy and make it more practical, more market-driven, and more Ugandan. The next step is to move from having a plan to adopting a policy.

Bamboo currently falls under several regulatory frameworks, with no single authority overseeing the sector. The policy push is being driven in part by Bamboo Uganda, a membership-based organization bringing together bamboo farmers and processors, among others. The organization aims to play a coordinating role similar to that historically played by the Uganda Coffee Development Authority in the coffee sector.

“If you want to make a sector meaningful for a country, you need coordination. Coffee became what it is because of an institution that aligned farmers, traders, exporters, and regulators. Bamboo needs the same kind of coordination.” He said.

The policy process is supported by the Belgian development agency, which is funding consultations and facilitating dialogue between the government and the private sector.

Industry players say the absence of clear regulations has constrained investment despite growing demand.

“At the moment, bamboo is everywhere and nowhere at the same time. As a farmer, you talk to forestry, as a charcoal producer, you talk to energy, as a builder, you talk to works. There is no single framework that enables the industry to function.” De Blois added.

Supporters of the policy argue that bamboo could play a significant role in environmental conservation. Bamboo grows rapidly, regenerates after harvesting, and can be harvested annually for decades, reducing pressure on natural forests.

According to Global Forest Watch (GFW), Uganda lost 1.2 million hectares of tree cover between 2001 and 2024, representing a 15% decline from the 2000 baseline. Bamboo has been identified as a key species for restoration.

“One acre of bamboo that is harvested sustainably can prevent the destruction of hundreds of acres of natural forest,” De Blois said. “If we get this right, bamboo can help reverse deforestation rather than contribute to it.”

Ms. Susan Kaikara, from the Ministry of Water and Environment, emphasized bamboo’s potential to drive Uganda’s green-growth agenda.

“Establishing a coherent national policy framework will strengthen coordination, inspire investment, and unlock bamboo’s full potential as a pillar of Uganda’s green economy,” she said.

Uganda’s charcoal market alone is estimated to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars annually, much of it supplied through unsustainable wood harvesting. Industry actors say certified bamboo charcoal plantations could offer a cleaner alternative.

“If they allow us to certify bamboo charcoal plantations, then we can get a trade license to compete or to work together with the existing market. We will reverse deforestation. We would enter an industry of about 500,000 hectares, creating smart, green jobs. We can digitalize them to make them attractive through bamboo agroforestry. So again, those things need a policy.” He adds.

Bamboo is also viewed as a climate-friendly crop due to its high capacity for carbon sequestration. Its rapid growth enables it to absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide, while its extensive root system improves soil structure and increases long-term carbon storage.

“When you look at carbon sequestration, bamboo offers several advantages. Residues from harvested bamboo can be converted into biochar, locking carbon into the soil for long periods. When you also see the sequestration per acre compared to many other trees, it is five or six times higher. So, we sequester a lot,” De Blois said

Stakeholders say that if the policy process progresses as planned, bamboo could emerge as one of Uganda’s key green growth sectors within the next decade.

“Policy making takes time. But what is important is that we have started the conversation with all the right ministries in the room. From here, it is about taking steady, practical steps.” He concluded.

Related posts:

As Uganda awaits the Energy Efficiency and Conservation law, plans to develop a five-year plan are underway.

As Uganda awaits the Energy Efficiency and Conservation law, plans to develop a five-year plan are underway.

REC25 & EXPO Ends with a call on Uganda to balance conservation and livelihood

REC25 & EXPO Ends with a call on Uganda to balance conservation and livelihood

Africa’s growth lies with smallholder farmers

Africa’s growth lies with smallholder farmers

Green Resources’ forestry projects are negatively impacting on local communities – donor

Green Resources’ forestry projects are negatively impacting on local communities – donor

WITNESS RADIO MILESTONES

A Global Report reveals that Development Banks’ Accountability Systems are failing communities.

Published

2 months agoon

December 4, 2025

By Witness Radio team.

For decades, development projects have been funded to address some of the World’s most pressing problems, including poverty, wildlife conservation, and climate change. However, what unfolds on the ground is sometimes the opposite of development. Instead of benefits, these projects have often harmed the very people they are supposed to support.

The effort to address such harm has led to the establishment of Independent Accountability Mechanisms (IAMs) by various development banks. Yet, communities affected by these projects often face betrayal by national court systems, leaving them feeling overlooked and vulnerable, emotions that underscore the urgent need for effective justice.

According to experts in development financing, since the early 1990s, development banks have sought to address and mitigate harm through IAMs—non-judicial grievance mechanisms that provide a direct avenue for impacted communities to raise concerns, engage with project implementers, and obtain remedies for the harm they have experienced.

The study, conducted by Accountability Counsel and titled Accountability in Action or Inaction? An Empirical Study of Remedy Delivery in Independent Accountability Mechanisms shows that while IAMs exist, their relevance has fallen short, underscoring the urgent need for reform to restore community trust and hope.

In compiling the report, researchers reviewed 2,270 complaints across 16 IAMs and conducted 45 interviews covering 25 cases globally.

The report reveals a persistent gap between the promise of remedies and their realization, highlighting that only 15% of closed complaints led to commitments, and just 10% achieved full completion, underscoring the urgent need for effective remedies for communities.

The findings highlight ongoing challenges, including inadequate implementation, limited monitoring, and persistent power imbalances, which continue to block communities from accessing meaningful remedies and demand immediate reform.

“The consequences of these institutional gaps are severe. As these cases show, institutional silence can exacerbate risk, while meaningful intervention can help de-escalate it.” The Report adds.

Uganda is among the countries where communities have sought justice using these accountability mechanisms. Between 2006 and 2010, communities in one of the districts of Uganda were brutally evicted by the UK-based Company, which was growing trees in the area.

The company was formerly an investee of the Agri-Vie Agribusiness Fund, a private equity fund supported by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private sector arm of the World Bank Group. The community filed a Complaint with the IFC’s accountability mechanism, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO).

“We complained to this body in 2011, hoping for justice, but over 15 years later our people are still struggling, living miserably, some without homes,” a community land and environmental defender told the Witness Radio team.

According to the affected residents, the CAO process did not lead to success or meaningful compensation, as they had hoped.

Between 2013 and 2014, the communities, with support from the CAO, signed a final agreement with the Company to address the harm. Among other commitments, this included resettlement of the affected communities.

In its 28-page report published in 2015 titled: A Story of Community-Company Dispute Resolution in Uganda, the CAO wrote,” With the agreements concluded, implementation is gathering pace. As agreed, the company has begun extending development assistance to both cooperatives, and the process of restoring and enhancing livelihoods has commenced.

The first step taken by both cooperatives was to acquire land. In late 2013, the Mubende Cooperative bought 500 acres of ‘fertile agricultural land’ in the Mubende district. Their vision was to allocate a certain percentage of the land for resettlement, with the remainder utilized for farming projects.

Reports from the ground indicate that communities remain dissatisfied with the process, claiming it failed to address their concerns fully and highlighting the urgent need for more effective remedy systems.

“When you say that people are well, it is really a total lie. Many people were never compensated or resettled. Even those who got a portion of land say they have never seen a fertile land—I have never seen it, because people are living or cultivating on rocky, infertile lands,” the defender further revealed.

The struggle faced by the Ugandan community is not unique. Their experience mirrors what the Accountability Counsel report identifies worldwide. Despite registering more than 2000 complaints by communities harmed by bank-financed projects globally, there has been no comprehensive system-wide analysis of whether and how often these mechanisms deliver meaningful remedies, defined as tangible, material outcomes that repair harm and improve lives.

In addition to the slow success of such IAMs, the report notes that, across interviews covering 25 complaints, 84% referenced retaliation, violence, or threats of violence-an alarming indicator of the risks faced by communities seeking justice, demanding immediate attention and action.

“Government officials and company representatives were frequently implicated in efforts to suppress dissent. This not only reduces the likelihood of achieving a substantial remedy, but also suppresses the willingness of community members to speak honestly and openly about Complaint outcomes.” The report further adds,

Further, it reveals that communities described a range of retaliatory tactics, including physical clashes, arrests, detentions, fatalities, intimidation and harassment, death threats, and anonymous warning letters, among others.

“Remedy must be reimagined not as a peripheral concern but as a core responsibility of development institutions. It must be adequately resourced, independently monitored, and centered around the needs and voices of affected people,” the report adds.

The report recommends that development banks and IAMs establish a Remedy Framework with clear standards to ensure remedies are timely, adequate, and community-centered, and to encourage stakeholders to prioritize systemic reform for better justice outcomes.

The report also urges development banks and their accountability mechanisms to make remedies a foundational element of responsible finance. Adopting institutional frameworks that prioritize redress, empowering IAMs to oversee and enforce commitments, and incorporating the outcomes of IAM processes into project evaluations and institutional learning.

Related posts:

Banks have given almost $7tn to fossil fuel firms since Paris deal, report reveals

Banks have given almost $7tn to fossil fuel firms since Paris deal, report reveals

Opinion: USAID needs an independent accountability office to improve development outcomes

Opinion: USAID needs an independent accountability office to improve development outcomes

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

Oxfam Report 2011: When Indigenous communities named Rwanda nationals by investor to run away from corporate accountability

Oxfam Report 2011: When Indigenous communities named Rwanda nationals by investor to run away from corporate accountability

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Young activists fight to be heard as officials push forward on devastating project: ‘It is corporate greed’

Published

5 months agoon

August 27, 2025

“We refuse to inherit a damaged planet and devastated communities.”

Youth climate activists in Uganda protesting the East African Crude Oil Pipeline, or EACOP, are frustrated with the government’s response to their demonstration as the years-long project moves forward.

According to the country’s Daily Monitor, youth activists organized with End Fossil Occupy Uganda took to the streets of Kampala in early August to protest EACOP. The pipeline, under construction since about 2017 and now 62 percent complete, is set to transport crude oil from Uganda’s Tilenga and Kingfisher fields through Tanzania to the Indian Ocean port of Tanga by 2026.

Activists noted the devastating toll, with group spokesperson Felix Musinguzi saying that already around 13,000 people “have lost their land with unfair compensation” and estimating that around 90,000 more in Uganda and Tanzania could be affected. End Fossil Occupy Uganda has also warned of risks to vital water sources, including Lake Victoria, which it says 40 million people rely on.

The group has been calling on financial institutions to withdraw funding for the project. Following a demonstration at Stanbic Bank earlier in the month, 12 activists were arrested, according to the Daily Monitor.

Some protesters were seen holding signs reading “Every loan to big oil is a debt to our children” and “It’s not economic development; it is corporate greed.”

Meanwhile, the regional newspaper says the government has described the activist efforts as driven by foreign actors who mean to subvert economic progress.

EACOP’s site notes that its shareholders include French multinational TotalEnergies — owning 62 percent of the company’s shares — Uganda National Oil Company, Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation, and China National Offshore Oil Corporation.

The wave of young people taking action against EACOP could be seen as a sign of growing public frustration over infrastructural projects that promise economic gain while bringing harm to local communities and ecosystems. Activists say residents face costly threats from pipeline development, such as forced displacement and the loss of livelihoods.

Environmental hazards to Lake Victoria could also disrupt water supplies and food systems, bringing the potential for both financial and health impacts. Just 10 years ago, an oil spill in Kenya caused a humanitarian crisis. The Kenya Pipeline Company reportedly attributed the spill to pipeline corrosion, which led to contamination of the Thange River and severe illness.

The EACOP project has already locked the region into close to a decade of development, and concerns about the pipeline and continued investments in carbon-intensive systems go back just as long. Youth activists, as well as concerned citizens of all ages, say efforts to move toward climate resilience can’t wait. “As young people, we refuse to inherit a damaged planet and devastated communities,” Musinguzi said, per the Monitor.

Source: The Cool Down

Related posts:

Put people above profits – Climate Activists urge Total to defund EACOP

Put people above profits – Climate Activists urge Total to defund EACOP

EACOP: The number of activists arrested for opposing the project is already soaring in just a few months of 2025

EACOP: The number of activists arrested for opposing the project is already soaring in just a few months of 2025

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

The East African Court of Justice fixes the ruling date for a petition challenging the EACOP project.

The East African Court of Justice fixes the ruling date for a petition challenging the EACOP project.

Why govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

Evicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Swedish pension fund drops TotalEnergies amid rising EACOP risks

Land tenure security as an electoral issue: Museveni warns Kayunga land grabbers, reaffirms protection of sitting tenants.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoWomen environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoUganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

-

FARM NEWS1 week ago

FARM NEWS1 week ago200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days agoEvicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days agoWitness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day agoWhy govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry