FARM NEWS

Agribusiness in Africa: Investor reveals which areas hold the most potential

Published

5 years agoon

Chris Isaac, chief investment officer of AgDevCo

by Betsy Henderson

Related posts:

Transforming Africa’s livestock sector is key to food security-Report

Transforming Africa’s livestock sector is key to food security-Report

EBRD launches new agribusiness strategy

EBRD launches new agribusiness strategy

Small scale farmers in Uganda, Kenya form online agricultural marketing platform to boost sales

Small scale farmers in Uganda, Kenya form online agricultural marketing platform to boost sales

FAO targets agriculture investments to end hunger In Africa

FAO targets agriculture investments to end hunger In Africa

You may like

-

Global agribusiness continues to displace rural communities

-

Agriculture sector allocated UGX 1.5 trillion to boost agro-production

-

Agoro irrigation water killing our crops – Farmers.

-

Smallholder Farmers Can Now Access Agricultural Credit Facility Without Collateral

-

Indian agribusiness sets sights on land in east Africa

-

Agriculture rebounds as economy recovers

FARM NEWS

200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

Published

4 weeks agoon

January 22, 2026

About 200 individuals consisting of rice farmers, small farmers, environmental activists and NGO representatives gathered in front of the parliament building in Kuala Lumpur to urge the government to cancel Malaysia’s participation in the 1991 UPOV convention.

The gathering aimed to submit two memorandums demanding the defense of the rights of small farmers who are alleged to be at risk if the amendment to the Protection of New Plant Varieties Act 2004 is continued.

Assembly spokesman Abdul Rashid Yob claimed that the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security (KPKM) submitted a draft amendment to the act to the UPOV Secretariat in Geneva last September.

“The involvement of foreign bodies in the formation of national laws without comprehensive consultation with stakeholders, including the governments of Sabah and Sarawak, is seen as a form of violation of national sovereignty.

“This amendment will revoke the traditional rights of small farmers to exchange and sell seeds, as well as limit the right to save seeds for the next breeding season,” he told reporters after handing over the memorandum.

The government has so far neither confirmed nor denied the allegations of submitting the draft act to the UPOV Secretariat.

Malaysiakini is trying to obtain clarification from Agriculture and Food Security Minister Mohamad Sabu and his officials regarding this allegation and issue.

Today’s gathering was organised by the Malaysian Food Sovereignty Forum (FKMM) and was also attended by representatives from the Malaysian Socialist Party (PSM) and the Mandiri student group.

The attendees carried various placards with slogans such as “Lift Farmers’ Rights”, “Students with Farmers”, “Farmers are not lazy” and “Reject Upov”.

Also on display was a large sketch of Mohamad showing the “good” finger gesture.

More than 50 uniformed police were present to control the rally, which proceeded without any disturbances.

Earlier, a memorandum was also given to Deputy Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development Chan Foong Hin, PN Chief Whip Takiyuddin and Gopeng MP Tan Kar Hing representing the Agriculture and Domestic Trade Special Select Committee (PAC).

All parties that received the memorandum promised to bring the issue to parliament.

Seed supply monopoly

Meanwhile, the coalition claims that the 1991 UPOV will only strengthen the monopoly of large companies on seed supply, thus eliminating traditional practices that have long been the backbone of local farmers’ survival.

“The existing PNPV Act 2004 is sufficiently balanced in protecting the rights of breeders and farmers, as well as safeguarding the interests of Indigenous communities and local biodiversity.

“Deleting the section relating to the prevention of biopiracy and the obligation to supply seeds at reasonable prices will only place the country’s seed policy under the influence of foreign powers,” he said.

Apart from the seed issue, rice farmers also raised the cost of living crisis which is becoming increasingly pressing due to the increasing cost of agricultural inputs and pressure on paddy prices in the market.

Among their main demands is a call for the government to set the maximum paddy grading rate at 20 percent to avoid losses for the farmers.

They also demanded that the government revise the price of paddy to RM1,800 per metric ton and make immediate improvements to the agricultural subsidy system.

They also complained about delays in fertilizer distribution, weak water management, and bureaucratic red tape in the disaster takaful scheme that made it difficult for them to receive compensation.

“The government needs to address the issue of leakages and weak governance in relevant agencies which have been alleged to be affecting the country’s rice production chain.

“If these demands are ignored, the country’s food sovereignty will continue to be threatened and dependence on imported seeds will increase dramatically,” he added.

Abdul Rashid added that UPOV 1991 is an international agreement that gives plant breeders intellectual property protection rights for new plant varieties they produce.

However, it became controversial after allegations that farmers were not free to store, exchange or resell protected seeds, unless permitted by national law.

Small-scale farmers do not agree with this agreement because it is seen as potentially detrimental to small farmers and only benefits large seed companies, as well as potentially threatening food sovereignty.

Source: malaysiakini.com

Related posts:

Seed Sovereignty: Most existing and emerging laws and policies on seeds are endangering seed saving and conservation on the African continent.

Seed Sovereignty: Most existing and emerging laws and policies on seeds are endangering seed saving and conservation on the African continent.

The EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025, is a potential threat to smallholder farmers, as it aims to disengage them from the agriculture business, according to experts.

The EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025, is a potential threat to smallholder farmers, as it aims to disengage them from the agriculture business, according to experts.

CSOs and Smallholder farmers are urgently convening to scrutinize the EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025.

CSOs and Smallholder farmers are urgently convening to scrutinize the EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025.

The EAC Seed and Plant Varieties Bill 2025 targets organic seeds, aiming to replace them with modified seeds, say smallholder farmers.

The EAC Seed and Plant Varieties Bill 2025 targets organic seeds, aiming to replace them with modified seeds, say smallholder farmers.

Farmers in the greater Kibaale area, covering Kagadi, Kakumiro, and Kibaale districts are counting losses after maize prices dropped sharply during the peak harvest season.

Many farmers said they had invested a lot of money, hoping for better profits, but the market prices let them down. They blamed the low prices on the high supply of maize, saying many people planted the crop after making good profits in the previous season.

Last season, a kilogramme of maize was sold between Shs900 and Shs1,000, but this season the price has fallen to between Shs500 and Shs700.

Farmers said the sharp drop has left them without profits, with only middlemen and casual workers benefiting.

Mr Dezii Katongore, a large-scale farmer in Kitonya Village, Bubango Sub-County in Kibaale District, said he spent more than Shs2m on pesticides, labour, and renting land to grow maize, expecting to earn more than Shs4m. He planned to harvest 90 sacks but only got 52 because of a long dry spell after planting.

“To my dismay, I sold at Shs750 per kilogramme instead of Shs1,000 as I had anticipated. Losses start even before the market stage. I had nowhere to store the maize. If I had kept it, it would have spoiled. I don’t know if I will farm maize again next season,” he said in an interview on September 8.

Similarly, Katangwe Birungi, a small-scale farmer from Kataara Village in Kibaale District, said he invested more than Shs1m in his four-acre maize farm at the start of the season.

He harvested 28 sacks, earning about Shs1.26 million instead of the more than Shs3 million he had expected. Mr Birungi said he was unable to raise enough money to pay school fees for his children. He now plans to switch to beans, saying their prices are more stable.

Mr Businge Byamukama, a resident of Kijungu Village in Kagadi District, shared a similar experience. He spent nearly Shs900,000 on labour and farm inputs for his two-acre maize garden but harvested only 27 sacks.

Mr Byamukama was forced to sell each kilogramme at Shs250, far below what he had hoped, earning just Shs1 million. He said from the little he earned, he had to clear a Shs300,000 loan, pay Shs200,000 in school fees, and settle hospital bills of Shs100,000.

What remained, he said, was hardly enough to take care of his family.

“I was forced to sell because I couldn’t afford storage. I am now planning to intercrop next season because relying on just one crop isn’t sustainable. I want to switch to beans,” he explained.

Mr Zimwanguhiiza Byaruhanga, a farmer from Kibaale District, said he invested about Shs800,000 in labour, pesticides, fertilisers, and seeds for his two-acre garden. He had expected at least 20 sacks but ended up with only 16.

“What we put in doesn’t match what we got out. We’ve been neglected, yet agriculture is a major contributor to the country’s economy. Why doesn’t the government set regulations to fix prices for farmers? We’re making losses on some of the money we invest, including bank and Sacco loans, and now we’re finding it hard to pay them back,” he said.

He said he had hoped to sell his maize at Shs1,000 per kilogramme, but the market only offered Shs500. Mr Byaruhanga accused middlemen of exploiting farmers by setting unfair prices during harvest time and urged government to step in and regulate the market. ‘

“Even after harvest, the middlemen manipulate measuring tapes to cheat us. But we have no choice—we must sell to support our families, pay loans, and school fees,” he said.

Source: Monitor

A smallholder tomato farmer in the northwestern Uganda region of West Nile sprays his half-acre tomato garden without adequate protection. Many farmers around the country interact with hazardous agro-chemicals without using adequate PPEs. COURTESY PHOTO/SASAKAWA AFRICA ASSOCIATION.

A consortium of civil society organisations (CSOs) has in a Jan.05 statement shown concern about the continued wrong use of dangerous pesticides in the country.

Members of the concerned CSOs mainly work to promote sustainable agricultural trade, food safety and sovereignty, climate justice, biodiversity restoration, and human and environmental rights.

The activists say there are growing concerns about pesticide misuse, including improper application and storage, counterfeit products, insufficient training in use, and use of poorly maintained or totally inadequate spraying equipment.

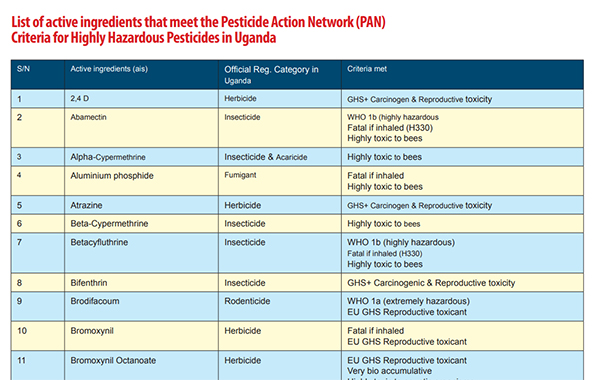

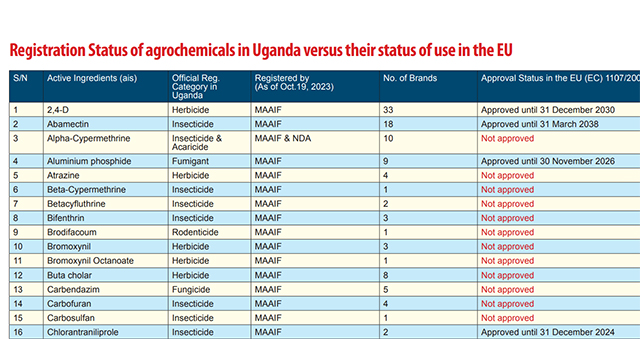

The activists insist the agriculture ministry should deregister at least 55 agro-chemicals that it registered in 2023 well-knowing that the same pesticides, herbicides and insecticides are banned by the European Union, a major market of Uganda’s agricultural produce.

Glyphosate-based herbicides, in particular, have raised significant alarm due to their potential environmental and health risks. Globally, they have been linked to contamination of water sources, soil degradation, and potential carcinogenic effects on humans.

In Uganda, glyphosate which appears in brands such as Rounduo and Weed Master, is widely used, especially among large-scale commercial farms and in weed control.

Betty Rose Aguti, the Policy and Advocacy Specialist at Caritas-Uganda who also doubles as the National Coordinator of Uganda Farmers Common Voice Platform says Uganda’s smallholder farmers need to be guided on the danger posed by some agro-chemicals.

“No one is guiding them on what to do with the agro-chemicals. Nobody is telling the farmers which agro-chemicals to use in what type of soils or on which type of crops and thereafter, what period of time they should take before they harvest.

“We have scenarios where some of these farmers apply these agro-chemicals bare-chested with no face masks and other protective gear; these farmers are using agro-chemicals as though they are using ordinary water.”

“They spray their gardens as they converse with their children and wives. In the course of doing this, they are inhaling the chemicals and after some time, they fall victim to the toxicity of these agro-chemicals and end up flooding the Uganda Cancer Institute,” she says.

What are pesticides?

Pesticides are defined by UN agencies; the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO), as substances or mixture of substances of chemicals or biological ingredients intended for repelling, destroying or controlling any pest, or regulating plant growth.

These often include ingredients that modify pest behaviour or their physiology (insect repellents) or affect crops during production or storage (herbicide safeners and synergists, germination inhibitors), as well as insecticides, fungicides and herbicides.

However, according to the activists, most of the chemicals on the Ugandan market are quite hazardous to both human health and the environment and yet they continue being used inappropriately by Ugandan smallholder farmers.

“We call upon the government of Uganda to regulate and ban all hazardous pesticides especially glyphosate and chlorpyriphos on the market in Uganda,” said Jane Nalunga, the Executive Director of the Uganda chapter of the Southern and Eastern Africa Trade Information and Negotiations Institute (SEATINI), a regional NGO that promotes pro-development trade, fiscal and investment-related poicies and processes.

Backbone of Uganda’s economy

The activists say Uganda’s agriculture sector is the mainstay of Uganda’s economy as it remains the main source of food, raw materials for industries, and employment of about 70% of Ugandans. The sector contributes about 24% to the country’s GDP.

“We cannot allow people with intellectual dishonesty to continue playing with the sector,” one of the activists said on Jan.5 during a press conference at the SEATINI-Uganda headquarters in Kampala. “We are aware that pesticides are significantly impacting health, biodiversity, socio-economic well-being, trade, and food security,” added Nalunga.

According to a 2020 World Health Organisation report, about 385 million cases of unintentional pesticide poisoning, including 11,000 deaths, mostly in low- and middle-income countries such as Uganda, are registered annually worldwide. According to UNICEF, pregnant and breastfeeding mothers, children under the age of five and the elderly are the most vulnerable to the effects of pesticides.

The activists say increased use of highly hazardous pesticides in Uganda is a threat to the right to adequate food, people’s livelihoods and farmers’ rights. They say pesticide runoff is reducing aquatic species diversity by 42% and threatening pollinators like bees. These insects are particularly critical for 75% of global crop production.

According to the European Environmental Agency, pesticides are intrinsically harmful to living organisms. When used outdoors, they can impact ecosystems even when they are intended to exclusively target a specific pest.

Herbert Kafeero, the Programme Manager at SEATINI-Uganda says the use of hazardous pesticides also has implications for trade. He says, in 2015, the government of Uganda imposed a self-ban on the export of agricultural produce to the EU because agro-chemical residues had been found in Uganda’s agricultural produce. “The self-ban was meant to address the challenges that were cited by the EU,” he says, “So we cannot ignore the fact that hazardous pesticides negatively impact the country’s trade and food security.”

He says, at the time, the government committed to retrain farmers and exporters to the EU regarding the EU’s sanitary and phytosanitary standards. Kafeero says the government must find solutions to the mushrooming agro-chemical dealers on the market.

“In every trading centre, you will not miss finding an agro-chemical shop and the person operating that agro-chemical shop presents himself as an expert when they actually are not.”

The activists want the Agricultural Chemicals Control Board under the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries to quickly profile the various agrochemicals, acaricides and inputs and their various sources that are available on the market in Uganda and ban the highly hazardous ones.

They also want the Department of Crop Inspection and Certification at the agriculture ministry to strengthen the regulation, management, use, handling, storage and trade of agrochemicals in the country.

They also want the government and other stakeholders to purposively plan and budget for education and awareness on the management, use, handling, storage and trade of agrochemicals in Uganda.

Prof. Ogenga Latigo disagrees

The activists were infact responding to Morris Ogenga Latigo, a Ugandan professor of entomology (study of insects) who had written an opinion on December 31, 2024, downplaying civil society’s concerns about hazardous pesticide and insecticide use in Uganda.

Prof. Ogenga Latigo in his article said the issue of agro-chemical use on farm pests and weeds and households was being exaggerated by civil society. He said the targeted agro-chemical inputs (pesticides, insecticides and herbicides) were being used in other countries.

The acrimonious debate has since sucked in the agricuture ministry. Stephen Byantware, the Director in charge of Crop Protection at the agriculture ministry told the media in Kampala recently that Uganda has an Agriculture Police Force and a Department of Inspection and Certification of agriculture inputs that “ensure that only nationally and globally approved agro-chemicals enter the Ugandan market.”

“The chemicals allowed into the country are those that have been approved,” he said, “There are no banned products on sale in Uganda. You cannot find DDT or Endosulfan in Uganda.”

But David Kabanda, the Executive Director of the Centre for Food and Adequate Living Rights, a Kampala-based non-profit, says Ugandans should know that hazardous pesticides have become one of the “loudest killers” and yet Ugandan smallholder farmers continue to associate with these chemicals on the farms, in the food stores, and in the homes.

“It’s only in Uganda where we don’t have a farmgate policy and yet we have scientific reports that have pointed out that the food we buy in markets in Kampala is contaminated.” “Don’t we see tomatoes and broccoli full of Mancozeb fungicide yet this chemical has been banned everywhere including the EU?”

“Pesticides are silent killers of humans, of nature, of our soils that are getting barren, of our water, of our agri-food system. I don’t imagine an agri-food system in Uganda without bees, without butterflies, and above all, without grasshoppers,” said Agnes Kirabo, the Executive Director of Food Rights Alliance (FRA).

Desperate smallholder farmers

According to the activists, Uganda’s agriculture system is by default largely organic but in recent years, pest and disease management has become one of the major production constraints for the country’s millions of subsistence farmers. And in recent years, farmers have turned to pesticides to control the pests.

According to the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations, the number of agricultural pesticides used in Uganda doubled in 12 years (2010 – 2022) from 2,990.23 tonnes to 6,009.78 tonnes.

Similarly, the monetary value of pesticides imported to Uganda more than doubled from US$ 32.57 million to US$75.87 million in 2022 with a peak import value of US$108.57 million reported in 2020. The lucrative agro-chemical business has attracted more than 40 registered pesticide importing companies in the country.

The activists say the increased use of pesticides is attributed to their use for weeding and the increased use of hybrid seeds and livestock. According to the CSOs, equally alarming is that many of these pesticides are “synthetic pesticides” which are persistent organic chemicals.

A study published last year by the Food Safety Coalition Uganda (FoSCU) titled: ‘‘Food Safety-Crop Protection Nexus: Insights from the Uganda’s agriculture sector,’’ noted that of the legally registered active ingredients, 47.8% (of the active ingredients) and 68.6% of the brands in Uganda qualified as “Highly Hazardous Pesticides.”

Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs) are classified as “reproductive toxicants” meaning they potentially can negatively affect the human reproductive system and have adverse effects on pregnancy outcomes and reduced fertility.

The same study noted that 15.6% of the registered active ingredients and 19.2% of the registered brands in Uganda qualified as highly hazardous pesticides in accordance with the FAO/WHO-Joint Meeting on Pesticide Management (JMPM) criteria.

According to the activists, by July 2023, over 65% of the 55 flagged active ingredients registered for use in Uganda and yet considered as highly hazardous pesticides according to the Pesticide Action Network (PAN) criteria, were not approved for use in the European Union economic bloc.

The majority (49%) of these pesticides are highly toxic to bees, 20% are carcinogenic and reproductive toxicants while 18% are probable carcinogens, and 9% are highly persistent in water and soil and are highly toxic to aquatic organisms.

They say that, based on the Uganda agrochemical register at the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF) and the National Drug Authority (NDA), the country had at least 115 active ingredients and 669 brands of synthetic pesticides legally registered for use in Uganda by the end of 2023.

“These are presenting in 459 brands, but all these active ingredients in the 459 brands, according to the PAN, are classified as highly hazardous,” said Bernard Bwambale, the head of programmes at the Global Consumer Centre, or CONSENT, who also coordinates the activities on food safety at the Food Safety Coalition of Uganda.

If it is hazardous in EU, it is hazardous in Uganda

Bwambale says his organisation has found that of the 55 active ingredients registered in Uganda, 65.5% of them cannot be used in their countries of origin. “Now, if a chemical, a highly hazardous chemical, is produced in a particular country and that country cannot use it, who are we to start thinking that we can use it? This is where our concern is.”

“So, whatever is not used in the EU, it means it’s not fit for use for human beings. The human beings in Uganda and the human beings in Europe are all human beings. And we are all sharing the same human rights.” He says some of the highly hazardous pesticides are mutagenic, meaning they can alter one’s DNA or genetic make-up.

“Literally, it would mean that when you consume food consisting of this kind of product, you stand a risk of your DNA or your genetic makeup being altered. And that is why some research is pointing to some of these chemicals being responsible for birth defects.” He says other chemicals are carcinogenic, meaning the chemical has the potential to cause cancer.

But Prof. Ogenga Latigo says some chemicals like Mancozeb the civil society claim are carcinogenic are not. He describes others as ‘probable carcinogens.’ A probable carcinogen is a substance that has a strong but not conclusive amount of evidence that it can cause cancer in humans.

But Bwambale says, “They don’t want people to keep confusing us with science.” He says other chemicals have been considered fatal when inhaled. “Imagine a farmer who doesn’t know these things and is spraying but is carrying a baby. So both the mother and the baby are inhaling this chemical,” he says, “We need to regulate these chemicals as much as we can.”

He says recent studies have indicated that some of these chemicals were found in human bodies –in sweat, urine and blood, in food and in water. “When the Europeans send us, for instance, these chemicals and we buy them, they also have regulations on which kind of food we can sell to them. We all know that.”

He says when farmers use these chemicals in the name of commercialising agriculture, they may produce very big tomatoes that do not rot, for example, but they cannot sell them beyond Uganda.

“You cannot put them on the EU market because they don’t meet the standard of the EU market. So they (agriculture products still remain with us,” he says.

Source: The independent

UPDF General on the spot over fresh evictions in Hoima

Small-scale fishers and coastal communities are pushing to testify before a human rights commission investigating the causes of food inequality in South Africa.

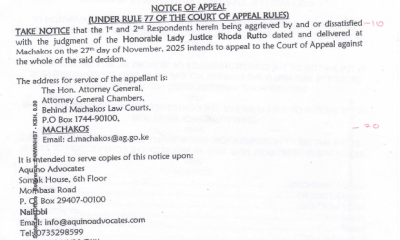

The Kenyan government insists on maintaining provisions of the Seed Act that the court nullified: farmers and legal experts question the motive.

FEATURE: What Lagos Can Learn From Kenya, Morocco, Uganda’s Forced Evictions

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Evicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks agoUS-DRC Strategic Partnership Agreement Faces Constitutional Challenge in Court

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoClose to six years on, Pangero Chiefdom subjects still linger in pain after the government army’s forceful takeover of their ancestral land.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoIndigenous communities’ complaint against World Bank-linked Nepal Cable Car Project declared eligible for investigation.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoDecades of land loss and chronic poverty: Salala Rubber Plantation prioritizes profit over the well-being of local Liberian communities.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoThe Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network Joint Radio program boosts Farmers’ knowledge of seed and food sovereignty.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days agoFEATURE: What Lagos Can Learn From Kenya, Morocco, Uganda’s Forced Evictions

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago13 years after the refugee host community was forcefully evicted to expand a refugee settlement, thousands remain unsettled.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days agoThe Kenyan government insists on maintaining provisions of the Seed Act that the court nullified: farmers and legal experts question the motive.