FARM NEWS

Communities in Africa fight back against the land grab for palm oil

Published

6 years agoon

Co-authored by: ADAPPE-Guinée, Bread for All (Switzerland), CDHD (Congo-Brazzaville), COPACO (DRC), Culture Radio (Sierra Leone), GRAIN, Joegbahn Land Protection Organization (Liberia), JVE Côte d’Ivoire, MALOA (Sierra Leone), Muyissi Environnement (Gabon), NRWP (Liberia), RADD (Cameroon), REFEB (Côte d’Ivoire), RIAO-RDC (DRC), SEFE (Cameroon), SiLNoRF (Sierra Leone), Synaparcam (Cameroon), UVD (Côte d’Ivoire), WRM, YETIHO (Côte d’Ivoire) and YVE Ghana.

Over the past decade, agribusiness companies have been increasing their production of palm oil to meet a growing global demand for cheap vegetable oil that gets used in the production of processed foods, biofuels and cosmetics. Community lands in many African countries are a main target for the expansion of their plantations.

In 2016, GRAIN reported that over 65 large-scale land deals for oil palm plantations in Africa had been signed between 2000-2015, covering over 4.7 million hectares.1 Multinational companies, in collaboration with local elites and development banks, had launched a full-scale attack against communities from Sierra Leone in West Africa to the DR Congo in Central Africa to take their lands for oil palm plantations.

Things have not, however, worked out entirely as the companies had hoped. Our updated accounting shows a significant decline in the number and total area of land deals for industrial oil palm plantations in Africa over the past five years, from 4.7 million hectares to a little over 2.7 million hectares. And only a small fraction of this area, 220,608 hectares, has been converted to oil palm plantations or replanted with new palms. We believe that strong resistance by communities has been key to slowing this expansion of industrial oil palm plantations in the region.

Communities in Africa have, by now, had more than enough experience with large-scale oil palm plantations to know that they are not needed nor wanted. Their traditional systems of oil palm cultivation and palm oil production are far more dynamic and far more capable of meeting the continent’s needs. It is time to completely stop the expansion of industrial oil palm plantations, and return the lands occupied by oil palm plantation companies to the affected communities.

The state of oil palm plantations in Africa

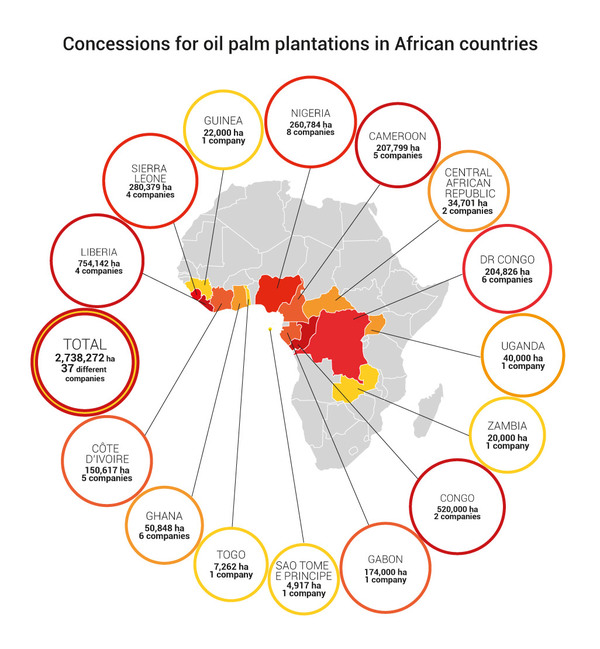

According to our updated data set, there are currently 49 large-scale concessions for oil palm plantations in Africa, covering 2.74 million hectares (see Annex I).

Many of the oil palm plantation projects that were announced over the past decade have failed or have been abandoned, as can be seen in the accompanying table (see Annex II). Other projects have been scaled back. And, while there have been some new projects and expansions since 2014, the pace has certainly slowed, with no announcements for new, large-scale oil palm plantation projects during the past two years.2

The geographic focus has narrowed as well. Nearly all the corporate oil palm plantation projects for Africa that were outside of Central and West Africa have been abandoned. The focus is now on a handful of countries, with the priorities being Cameroon, the DR Congo, Congo-Brazaville, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone. There is also activity, but to a lesser extent, in the Central African Republic, Guinée, Sao Tome e Principe, Togo and Uganda.

Another central point that emerges from the updated data set is the massive discrepancy between the area that corporations have acquired under concessions and the area that they have converted to industrial oil palm plantations. Only 463,000 hectares or 17% of the total area acquired under concessions (2.74 million hectares) is planted with oil palms, with another 55,000 ha planted for rubber and other crops within these concessions. Moreover, the majority of these corporate plantations are old plantations that date back to the parastatal projects of the 1970s and 1980s or even further back into the colonial era. We estimate that only 220,608 hectares have been developed into industrial oil palm plantations or replanted over the past decade.3

The most clear case is in Congo-Brazzaville. Of the 520,000 ha in concessions that the government awarded to palm oil companies, less than 1,000 ha or 0.2% has been developed into plantations. It seems likely that these concessions were merely fronts to facilitate illegal logging operations by converting forested areas to agricultural lands.4 Liberia provides another example. During the administration of President Sirleaf, the first elected government following the country’s horrific civil war, 755,000 ha were handed out to oil palm plantation companies in concessions. But today, less than 54,000 ha (7% of the total concession areas) have been developed into industrial plantations, even though some of the largest oil palm plantation companies in the world have acquired these concessions.

The big companies driving the expansion

The 2016 data set identified a long list of companies, some big, many of them small and with little experience in agriculture, that were acquiring lands for industrial oil palm plantations in Africa. But the updated data set shows that many of these small and inexperienced operators have disappeared. Today, the expansion of industrial oil palm plantations in Africa is dominated by a handful of large, multinational companies. Just five companies control about three-quarters of the planted, industrial oil palm plantation area on the continent (see Table 1).

Some of these companies are big Southeast Asian oil palm plantation companies, such as Sime Darby, Golden Agri, KLK, Salim Group, and Olam. Each of these companies have one major oil palm plantation project in Africa. Wilmar, which is based in Singapore, is the most active of the Southeast Asian oil palm plantation companies. It has oil palm plantation operations in five African countries (Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, Uganda), with 83,714 ha planted.

The other key companies operating oil palm plantations in Africa are the old European colonial agribusiness companies. The two most important are SOCFIN of Luxembourg and SIAT of Belgium. Both of these companies have built their plantation empires upon the ruins of a World Bank programme to construct oil palm and rubber plantations across several countries in West and Central Africa in the 1970s and 1980s. That programme was carried out in close collaboration with SOCFIN’s consulting firm, SOCFINCO. SIAT’s founder and co-owner was a member of the SOCFINCO team at the time.

Under this World Bank programme, SOCFINCO oversaw the development of blueprints for national oil palm and rubber plantation programmes, helped identify the lands for conversions to industrial plantations, and was paid to manage the plantations and, in some cases, oversee the sales of the rubber and palm oil by the state plantation companies established through the programme (see box: The World Bank and SOCFIN/SIAT’s plantation projects in Nigeria). The World Bank provided loans to the African governments for these projects, and then, in the 1990s, with the state plantation companies deep in debt, it pushed for privatisation. SOCFIN and SIAT ended up with several of the most prized plantations.5

Today SOCFIN and SIAT have a combined total of 123,336 hectares planted to oil palm plantations in Africa (91,081 ha for SOCFIN and 32,255 for SIAT). These two companies therefore control a quarter of all the large oil palm plantations on the continent.

Table 1. Top five oil palm plantations companies in Africa

|

Company |

Area under oil palm plantations (ha) |

Countries |

|

SOCFIN (Luxembourg) |

93,764* |

Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, DRC, Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria, Sao Tome e Principe, Sierra Leone |

|

Wilmar (Singapore) |

83,714** |

Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, Uganda |

|

Olam (Singapore) |

71,500 |

Gabon |

|

SIAT (Belgium) |

32,415 |

Ghana, Nigeria |

|

Feronia (Canada) |

23,500 |

DRC |

* Includes plantations owned by SOGUIPAH in Guinea.

**Includes plantations owned by SIFCA in Liberia. Wilmar owns 27% of SIFCA.

The World Bank remains an important actor in driving the expansion of industrial oil palm plantations in Africa, particularly through its International Finance Corporation. But it is not the only development bank active in this area. There are numerous development finance institutions (DFIs) that are involved in corporate oil palm plantations in Africa. Most of them are from European countries, but there are also DFIs from the US and China that are involved, as well as several African-based development banks, such as the African Development Bank and the West African Development Bank. Often the DFIs channel their money into plantation companies through private equity funds that are based in offshore tax havens, such as the African Agricultural Fund in Mauritius, which has shares in Goldtree (Sierra Leone) and Feronia (DR Congo).

Typically these DFIs provide loans to oil palm plantation companies on favourable terms. In some cases, they have provided support at the outset of the project, while in other cases they have stepped in to enable a company to expand its plantations or to keep it from going bankrupt. In certain cases, DFIs have even acquired shares in plantation companies and have taken seats on their boards of directors, such as with Feronia Inc in the DR Congo and Goldtree in Sierra Leone, in which DFIs now constitute the companies’ majority owners.

It is likely that without the current and historical involvement of the World Bank and other DFIs, many of the industrial oil palm plantations that exist in Africa today would never have gotten off the ground. For those of us working to stop palm oil companies from grabbing lands, it is thus important to keep pressuring DFIs to stop funding these industrial plantations.

Resisting the land grab

There are at least 27 large scale oil palm plantation projects reported or announced over the past decade that were abandoned or have failed. Numerous other projects have been scaled back or have stalled. These projects were supposed to transform over 3.1 million ha of land into industrial plantations, but they have not come near to this figure.

One reason for this failure is that many of the projects were led by companies with little or no previous experience with large scale agriculture. Some of these companies simply wanted to profit on the rush for farmland in Africa, and most were interested in securing leases or concessions over large areas of land that they could then sell to another company after making minor investments in operations or no investments at all. Other companies, such as China’s ZTE in the DR Congo, the Singapore-based Siva Group in Cameroon and Sierra Leone or India’s Karuturi in Ethiopia, lacked the capacity to carry out the projects they had embarked upon.

But a more important explanation for the difficulties that companies have had in pushing through on their projects is the resistance that they encountered from affected communities and groups supporting these communities. Protests by villagers in the Rufiji District of Tanzania killed a 20,000 ha industrial oil palm plantation project by the British company African Green Oil Ltd.6 An intense struggle by communities in southwestern Cameroon, supported by community organisations and national and international groups, forced the government to scale back the concession it granted to US firm Herakles Farms from 73,000 ha to less than 20,000 ha. Ultimately the US company backing the venture pulled out, and the new investors have been unable to move ahead with the project.7

Other villagers in Cameroon have stopped the expansion of Pamol’s plantations or are fighting protracted battles to get their lands back and stop the expansion of SOCFIN’s subsidiary Socapalm.8

In Liberia, the Joegbahn clan stopped the UK company Equatorial Palm Oil, now owned by one of the largest oil palm plantation companies in the world, from taking their lands for plantations, despite the government having provided these lands to the company under a concession agreement.9 The other major palm oil companies operating in Liberia are also coming up against fierce resistance from villagers and their partner organisations, as they try to carry out their industrial plantation plans.10

Land conflicts are costly for companies. The fact that so many industrial oil palm plantation projects in Africa are embroiled in land conflicts has the effect of discouraging companies from pursuing investments. The resistance to Herakles Farms, for instance, surely influenced the decisions of the international food corporations Cargill and Sime Darby to pull back from pursuing oil palm plantations in Cameroon. The international criticism of development banks for their funding of Feronia’s plantations in the DR Congo has likely caused them to refuse funding for other industrial oil palm plantation projects in Africa. While there is no way for us to say for sure which projects or how many projects were shelved because of risks of land conflicts or local resistance, we do know from our experience in different struggles that resistance is having a big impact on their decisions and capacity to move industrial plantation projects forward.

The final chapter for industrial oil palm plantations in Africa

West and Central Africa are the origins of the oil palm. It is deeply embedded in the culture and history of most countries in the region– providing not only an important source of cooking oil to many, many generations of communities, but also beverages, animal feed, textiles, building materials, medicines and all kinds of spiritual and ceremonial uses.11 The local production of palm oil was thriving until it was brutally interrupted by a colonial occupation in which much of the region’s oil palm forest groves were put at the service of foreign companies and huge areas of lands were violently taken over to make way for the world’s first large-scale oil palm plantations.

The European colonial rulers selected from the diverse African palms and, with the same brutal force, established massive oil palm plantations in Southeast Asia. The cheap palm oil produced on these plantations, with virtual slave labour, would eventually be shipped back to Africa, turning a region that once had no problem to produce surpluses of palm oil, into a major importer.

The post-colonial period was not much better for communities in the region. Through the cover of the World Bank’s African plantation programmes of the 1970s and 1980s, the old colonial plantation companies were able to re-establish their presence in the region (see box: The World Bank and SOCFIN/SIAT’s plantation projects in Nigeria). In fact, because the oil palm plantation expansion during these years was led by parastatal companies claiming to act in the national interest, the companies could rely on governments to use Presidential decrees and the brute force of the army to displace people from the best lands for oil palm cultivation. The African governments also used public money to pay for this expansion, by way of loans from the World Bank, and then handed the plantations over to foreign companies in the 1990s and 2000s, through the privatisation processes forced upon them by the World Bank, as part of so-called structural adjustment programmes.

The World Bank pursued a programme to develop large-scale palm oil production in Nigeria in the 1970s and 1980s with the Nigerian government. This programme, financed by multi-million dollar loans from the World Bank and other development banks and ultimately paid for by the Nigerian public, was drawn up and executed by SOCFINCO, a consultancy firm created by the Belgian colonial plantation company SOCFIN, in association with the Dutch company HVA. The person leading SOCFINCO’s operations in Nigeria was the founder of SIAT, Pierre Vandebeeck. From 1974 to the end of the 1980s, SOCFINCO crafted master plans for at least 7 World Bank-backed oil palm projects in 5 different states. Each project involved the creation of a parastatal company that would both take over the state’s existing plantations and develop new plantations and palm oil mills as well as large-scale outgrower schemes.

SOCFINCO was then hired, with lucrative management fees, to handle the project management. All of the projects generated enduring land conflicts with local communities, such as with the Oghareki community in Delta State or the villagers of Egbeda in Rivers State. After dispossessing numerous communities from their lands and incurring huge losses for the Nigerian government, the parastatal companies were then privatised, with the more valuable of the plantation assets ending up in the hands of SOCFIN or SIAT, which Vandebeeck formed in 1991 to take over the plantations of the Oil Palm Company Ltd of Bendel State (now divided into Edo State and Delta State). These plantations are now operated by SIAT’s Nigerian subsidiary Presco. In 2011, another SIAT subsidiary in Nigeria, SIAT Nigeria Limited, acquired the 16,000 ha of plantations of the Rivers State palm oil company, Risonpalm, which Vandebeek, as staff of SOCFINCO, had overseen as plantation manager during the World Bank programme from 1978-1983.

SOCFIN, for its part, took over the oil palm plantations in the Okomu area that were developed under the World Bank programme. It was SOCFINCO that first identified this area for plantation development as part of the appraisal study it was hired to undertake in 1974. The Okomu Oil Palm Company Plc. (OOPC) was subsequently established as a parastatal company in 1976 and 15,580 ha of land within the Okomu Forest Reserve of Edo State was de-reserved and taken from the local communities to make way for oil palm plantations. The company hired SOCFINCO as the managing agent to oversee its activities from 1976-1990. Reports vary, but at some point between 1986 and 1990, OOPC was then divested to SOCFIIN’s subsidiary Indufina Luxembourg.12

The new wave of industrial oil palm plantations that has taken place in Africa over the past 15 years is built, quite literally, on the back of this brutal history. The majority of recent industrial oil palm projects that are being implemented involve old concessions, abandoned plantations and long simmering land conflicts.

For communities across African countries, today’s industrial oil palm plantation projects are experienced as another round of colonial occupation.13 Their lands are being taken from them, often by force, without consultation or consent. The industrial plantations destroy their forests and local biodiversity and pollute their water sources. They lose access to lands to grow food as well as their traditional palm groves, and they are forbidden from producing their own palm oil. The companies are only able to produce palm oil for cheap because the labour conditions on their plantations are so bad, often even worse than they were in colonial times, with wages, when they are paid, not covering basic living expenses and the vast majority of jobs being for daily labourers, with no job security. There are barely any social investments, such as schools, clinics and infrastructures, that might provide some compensation– and villagers rarely see any of the rental payments that companies claim to make.

Much like under the colonial period, villagers living in and around the concession areas are constantly harassed and beaten by company security guards who accuse them of stealing palm fruits from the company plantations. Opponents of the company are also routinely beaten, arrested and intimidated, and sometimes even killed. But it is women who suffer the most, and almost always in silence. The level of sexual violence faced by women living around the plantations or working at the plantations is generally horrific.14

Yet today’s agrocolonialism is nevertheless cloaked in the story of a mission to help Africa, just as it was during the colonial period. All of the companies claim to be “responsible investors”, with several adhering to the principles of the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) and making ‘zero deforestation’ pledges. Although the RSPO certification criteria cannot be considered sustainable, since it promotes industrial plantations, it is interesting to see how few of these companies have achieved RSPO certification for their industrial plantations in African countries. Only 9 of the 52 large scale oil palm plantations in operation in Africa have RSPO certification.

Most of the corporate plantation projects include outgrower schemes, where the companies organise local smallholders to supply them with oil palm fruits. Sometimes, companies lure farmers into these programmes by providing seedlings and promising that such schemes are a way for villagers to ‘get rich quickly’. These programmes are sometimes written into the concession agreements with the government and companies often receive funding from African governments, UN institutions, donors or development banks for these outgrower or smallholder programmes. In several cases, the schemes are carried out with the collaboration of NGOs. Some outgrower schemes have existed for decades, and were established through the World Bank funded industrial oil palm programmes of the 1970s and 1980s. This is the case in Ghana, where the area under outgrower schemes is larger than the area under industrial plantations.15 In most recent cases, however, these outgrower schemes are not the priority for the companies, and the companies channel far more of their resources into their own company plantations, for which they can maintain stricter control over production.

Olam, for example, established a joint venture company with the Gabon government to develop ‘outgrower’ programmes in nine provinces to allegedly support the country’s food security. The programme, called GRAINE, is supposed to develop smallholder plantations of oil palms and other crops covering 200,000 ha and involving 1,600 villages by 2020. Yet, by the end of 2017, the joint venture had invested $40 million in the GRAINE programme, in contrast with the $643 million that Olam’s plantation company spent on its own industrial plantations. Moreover, rather than increase food production, the GRAINE programme had instead devoted the funding it received from the African Development Bank to the development of a large oil palm plantation on a 30,000 ha concession in the savannah zone at Ndendé in Ngounié province.16 A recent report indicated that this GRAINE oil palm plantation may now be handed over to Olam’s plantation company!17

Where companies are actually implementing outgrower programmes or maintaining the smallholder schemes initiated by the previous plantation owners, the results are not much better. The villagers participating in these programmes have to cultivate industrial oil palms exclusively on part or on all of their lands and must produce exclusively for the company. The company sets the terms of the contract and determines the prices that are paid. Experience shows that the companies typically fix the contracts to guarantee their profits, while the villagers end up in debt at the end of each year. The villagers also sacrifice lands that they could have used to produce food for their families and communities.

Corporate oil palm projects are clearly a disaster for the local communities where they are based. The number of failed projects and the losses incurred by many active plantation companies at their operations in Africa seem to indicate that the companies are not profiting much either. But this does not mean that the main people behind these companies do not profit. The executives and directors of loss making oil palm plantation companies always ensure that they are paid handsomely, through salaries, bonuses, share options and all kinds of “service fees” or exaggerated expenses that they charge to the companies. While a company like Feronia Inc, which is heavily financed by development banks, complains of not being able to pay its workers even the legal minimum wage or to build decent health clinics within its concession in the DR Congo, its top executives received over $2 million in salaries and share options in 2017.18 Moreover, when there are (declared) profits, such as with some of the SOCFIN owned plantation companies in Africa, most of the profits are distributed to the shareholders, and are not used to improve the wages of its workers or to construct the social projects that were promised to communities.19

Turning the page

The experience with this latest wave of industrial oil palm plantations in Africa makes it clear that this model of corporate agriculture is totally inappropriate and ineffective for the continent. Villagers in many parts of the region have a long history of cultivating oil palms and producing palm oil without the involvement of big companies, and women are usually the main actors in these small scale systems. Today, smallholders in African countries, supplying small-scale mills, account for the vast majority of palm oil that is produced on the continent, and they are far more capable of expanding production to meet the growing local demand, if they have access to lands and markets.20 They also produce a palm oil that is of higher quality and more suited to local food cultures, whereas the industrial plantations produce a highly-refined palm oil designed for industrial uses, including unhealthy, ultra-processed foods and biofuels.

Despite all the support they get from governments, banks and donors, the plantations of the big palm oil companies still account for only 10% of the total harvested area of oil palms in Africa.21 Most of the palm oil that the big companies sell in Africa is imported from Malaysia and Indonesia and this cheap, low quality palm oil undercuts the local markets for the higher-quality traditional palm oil supplied by small-scale producers.

It is the history of diverse small scale production that needs to be the foundation for the future of palm oil production on the continent. Communities do not need companies to manage their lands and to produce palm oil. As we have seen over the past decades, companies only drain the profits to far away places and their model of production leaves nothing but misery and pollution for local people.

For all of these reasons, there needs to be an immediate ban on all future, large-scale oil palm plantation projects and a halt to those currently being implemented. Where large-scale plantations already exist, the lands must be returned to the control of the local communities, who can then develop a vision for how they want to utilise and organise these lands, now and into the future. The concession agreements governments have signed with companies, most of which are in violation of the law and the rights of the local communities, must be scrapped.

It is time to turn the page on colonial plantations in Africa, and put oil palms back into the hands of communities!

1 GRAIN, “The global farmland grab in 2016: how big, how bad?”, June 2016: https://www.grain.org/e/5492

2 The exception is the company Africa Palm Corp which claims to have secured agreements with Guinea-Bissau, Republic of the Congo, Togo and Ghana covering 5 million hectares. There is little evidence, however, to indicate that this company will be able to move forward with these projects.

3 This comprises the plantation areas developed/replanted by Pamol, Nana Bouba Group, Palme d’Or, Agro Panorama, DekelOil, Feronia, Blattner, Volta Red, Olam, Golden Agri, KLK, SIFCA (Liberia), Sime Darby, Goldtree, Kalyan Agrovet and IDC, as well as the expanded/replanted areas by SOCFIN (27,980 ha), Wilmar (27,231 ha), SIAT (8,605 ha).

4 Earthsight, “The Coming Storm,” March 2018: https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/624187_3b22354dff0843789fc440cb4674caaf.pdf

5 SOCFIN and SIAT acquired plantations that were developed and or privatised by way of World Bank programmes in Cameroon (Socapalm), Côte d’Ivoire (SOGB), Gabon (Agrogabon, now owned by Olam), Ghana (GOPDC and SIPL) and Nigeria (Presco, SIAT Nigeria, and Okomu).

6 Kizito Makoye, “Tanzanian Farmers Crack the Code for Fighting Land Grabs” MSN, November 2018: https://www.msn.com/en-xl/africa/life-arts/tanzanian-farmers-crack-the-code-for-fighting-land-grabs/ar-BBPDXXv

7 WRM, “Palm oil concessions for logging: the case of Herakles Farms in Cameroon,” September 2015: https://wrm.org.uy/articles-from-the-wrm-bulletin/section1/palm-oil-concessions-for-logging-the-case-of-herakles-farms-in-cameroon/

8 Fern, .Speaking truth to power: the village women taking on the palm oil giant,” September 2018: https://www.fern.org/news-resources/speaking-truth-to-power-the-village-women-taking-on-the-palm-oil-giant-45/

9 Silas Kpanan’Ayoung Siakor and Jacinta Fay, “When our land is free, we’re all free,” Synchronicity Earth, https://www.synchronicityearth.org/when-our-land-is-free-were-all-free/

10 Ashoka Mukpo, “‘We come from the earth’: Q&A with Goldman Prize winner Alfred Brownell”, Mongabay, June 2019: https://news.mongabay.com/2019/06/we-come-from-the-earth-qa-with-goldman-prize-winner-alfred-brownell/

11 GRAIN, “Planet palm oil: peasants pay the price for cheap vegetable oil”, September 2014: https://grain.org/e/5031

12 Much of the information from the period of the World Bank programme is derived from the World Bank archives (http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/506921468098056629/pdf/multi-page.pdf; http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/735641468915257440/text/multi0page.txt; http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/328231468082133313/text/multi-page.txt; http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/735641468915257440/text/multi0page.txt; http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/477341468075533881/pdf/multi-page.pdf). See also Emmanuel Okachukwu A. Omah, “Public Enterprises and Community Development in Rivers State: A case study of Risonpalm Limited,” June 2002: https://oer.unn.edu.ng/download/public-enterprises-and-community-development-in-rivers-state-a-case-study-of-risonpalm-limited; Nwizugbe Obiageri Ezenwa, “Corporate Community Crisis in Nigeria; Case Study of Presco Industries Ltd and Oghareki Community,” IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science, March 2014: http://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol19-issue3/Version-7/J019378289.pdf; and documentation from the evaluations of Okomu’s extension plans from 2016 conducted by Proforest and Foremost Development Services Limited.

13 World Rainforest Movement, GRAIN and an Alliance of community and local organisations united against industrial oil palm plantations in West and Central Africa, “Booklet: 12 tactics palm oil companies use to grab community land’ April 2019: https://grain.org/e/6171

14 RADD, Muyissi Environnment, Natural Resource Women Platform, Culture Radio, GRAIN, WRM, “Breaking the Silence: Violence against women in and around industrial oil palm and rubber plantations,” https://wrm.org.uy/all-campaigns/breaking-the-silence-violence-against-women-in-and-around-industrial-oil-palm-and-rubber-plantations/

15 Kwabena Ofosu-BUDU and Daniel Bruce SARPONG, “Oil palm industry growth in Africa: A value chain and smallholders’ study for Ghana,” Chapter 11, FAO: http://www.fao.org/3/i3222e/i3222e11.pdf

16 RADD, SEFE, YETHIO, SYNAPARCAM, GRAIN and WRM, “The seed of despair: communities lose their land and water sources due to OLAM’s agribusiness in Gabon,” 11 July 2017, https://grain.org/e/5755

17 “Gabon: la gestion du projet Graine cédée à la CDC,” Gabon Media Time, Novembre 2018: https://pmepmimagazine.info/gabon-la-gestion-du-projet-graine-cedee-a-la-cdc/

18 According to Feronia Inc’s annual report for 2017, available here: https://www.sedar.com

19 See Socfinaf’s 2018 annual report: https://www.socfin.com/sites/default/files/2019-04/Rapport%20annuel%20-%20Socfinaf%282018%29.pdf

20 Ordway, Elsa M et al. “Oil palm expansion and deforestation in Southwest Cameroon associated with proliferation of informal mills.” Nature communications vol. 10,1 114. 10 January 2019: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6328567/

21 According to FAOSTAT, the total harvested area in Africa in 2017 is 4,578,074 ha.

Related posts:

Uganda: Local communities claim they are not benefiting from Green Resources’ subsidiary’s carbon credit initiative; incl. company’s comments

Uganda: Local communities claim they are not benefiting from Green Resources’ subsidiary’s carbon credit initiative; incl. company’s comments

The Agony of a Tree-Planting Project on Communities’ Land in Uganda

The Agony of a Tree-Planting Project on Communities’ Land in Uganda

New programme takes over palm oil growing in Uganda

New programme takes over palm oil growing in Uganda

Multinationals use COVID-19 crisis to violently grab land of poor communities with impunity

Multinationals use COVID-19 crisis to violently grab land of poor communities with impunity

You may like

-

Six cattlemen opposed to the Tilenga oil project-related forced land eviction have been granted bail but will remain in prison…

-

Uganda government ignores its directive on COVID evictions, evicts thousands of smallholder farmers, artisanal miners.

-

Global agribusiness continues to displace rural communities

-

The global farmland grab goes green

-

Court releases a tortured community land rights defender on bail

-

Breaking! Kiryandongo human rights situation is presented before the United Nations…

FARM NEWS

200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

Published

4 weeks agoon

January 22, 2026

About 200 individuals consisting of rice farmers, small farmers, environmental activists and NGO representatives gathered in front of the parliament building in Kuala Lumpur to urge the government to cancel Malaysia’s participation in the 1991 UPOV convention.

The gathering aimed to submit two memorandums demanding the defense of the rights of small farmers who are alleged to be at risk if the amendment to the Protection of New Plant Varieties Act 2004 is continued.

Assembly spokesman Abdul Rashid Yob claimed that the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security (KPKM) submitted a draft amendment to the act to the UPOV Secretariat in Geneva last September.

“The involvement of foreign bodies in the formation of national laws without comprehensive consultation with stakeholders, including the governments of Sabah and Sarawak, is seen as a form of violation of national sovereignty.

“This amendment will revoke the traditional rights of small farmers to exchange and sell seeds, as well as limit the right to save seeds for the next breeding season,” he told reporters after handing over the memorandum.

The government has so far neither confirmed nor denied the allegations of submitting the draft act to the UPOV Secretariat.

Malaysiakini is trying to obtain clarification from Agriculture and Food Security Minister Mohamad Sabu and his officials regarding this allegation and issue.

Today’s gathering was organised by the Malaysian Food Sovereignty Forum (FKMM) and was also attended by representatives from the Malaysian Socialist Party (PSM) and the Mandiri student group.

The attendees carried various placards with slogans such as “Lift Farmers’ Rights”, “Students with Farmers”, “Farmers are not lazy” and “Reject Upov”.

Also on display was a large sketch of Mohamad showing the “good” finger gesture.

More than 50 uniformed police were present to control the rally, which proceeded without any disturbances.

Earlier, a memorandum was also given to Deputy Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development Chan Foong Hin, PN Chief Whip Takiyuddin and Gopeng MP Tan Kar Hing representing the Agriculture and Domestic Trade Special Select Committee (PAC).

All parties that received the memorandum promised to bring the issue to parliament.

Seed supply monopoly

Meanwhile, the coalition claims that the 1991 UPOV will only strengthen the monopoly of large companies on seed supply, thus eliminating traditional practices that have long been the backbone of local farmers’ survival.

“The existing PNPV Act 2004 is sufficiently balanced in protecting the rights of breeders and farmers, as well as safeguarding the interests of Indigenous communities and local biodiversity.

“Deleting the section relating to the prevention of biopiracy and the obligation to supply seeds at reasonable prices will only place the country’s seed policy under the influence of foreign powers,” he said.

Apart from the seed issue, rice farmers also raised the cost of living crisis which is becoming increasingly pressing due to the increasing cost of agricultural inputs and pressure on paddy prices in the market.

Among their main demands is a call for the government to set the maximum paddy grading rate at 20 percent to avoid losses for the farmers.

They also demanded that the government revise the price of paddy to RM1,800 per metric ton and make immediate improvements to the agricultural subsidy system.

They also complained about delays in fertilizer distribution, weak water management, and bureaucratic red tape in the disaster takaful scheme that made it difficult for them to receive compensation.

“The government needs to address the issue of leakages and weak governance in relevant agencies which have been alleged to be affecting the country’s rice production chain.

“If these demands are ignored, the country’s food sovereignty will continue to be threatened and dependence on imported seeds will increase dramatically,” he added.

Abdul Rashid added that UPOV 1991 is an international agreement that gives plant breeders intellectual property protection rights for new plant varieties they produce.

However, it became controversial after allegations that farmers were not free to store, exchange or resell protected seeds, unless permitted by national law.

Small-scale farmers do not agree with this agreement because it is seen as potentially detrimental to small farmers and only benefits large seed companies, as well as potentially threatening food sovereignty.

Source: malaysiakini.com

Related posts:

Seed Sovereignty: Most existing and emerging laws and policies on seeds are endangering seed saving and conservation on the African continent.

Seed Sovereignty: Most existing and emerging laws and policies on seeds are endangering seed saving and conservation on the African continent.

The EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025, is a potential threat to smallholder farmers, as it aims to disengage them from the agriculture business, according to experts.

The EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025, is a potential threat to smallholder farmers, as it aims to disengage them from the agriculture business, according to experts.

CSOs and Smallholder farmers are urgently convening to scrutinize the EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025.

CSOs and Smallholder farmers are urgently convening to scrutinize the EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025.

The EAC Seed and Plant Varieties Bill 2025 targets organic seeds, aiming to replace them with modified seeds, say smallholder farmers.

The EAC Seed and Plant Varieties Bill 2025 targets organic seeds, aiming to replace them with modified seeds, say smallholder farmers.

Farmers in the greater Kibaale area, covering Kagadi, Kakumiro, and Kibaale districts are counting losses after maize prices dropped sharply during the peak harvest season.

Many farmers said they had invested a lot of money, hoping for better profits, but the market prices let them down. They blamed the low prices on the high supply of maize, saying many people planted the crop after making good profits in the previous season.

Last season, a kilogramme of maize was sold between Shs900 and Shs1,000, but this season the price has fallen to between Shs500 and Shs700.

Farmers said the sharp drop has left them without profits, with only middlemen and casual workers benefiting.

Mr Dezii Katongore, a large-scale farmer in Kitonya Village, Bubango Sub-County in Kibaale District, said he spent more than Shs2m on pesticides, labour, and renting land to grow maize, expecting to earn more than Shs4m. He planned to harvest 90 sacks but only got 52 because of a long dry spell after planting.

“To my dismay, I sold at Shs750 per kilogramme instead of Shs1,000 as I had anticipated. Losses start even before the market stage. I had nowhere to store the maize. If I had kept it, it would have spoiled. I don’t know if I will farm maize again next season,” he said in an interview on September 8.

Similarly, Katangwe Birungi, a small-scale farmer from Kataara Village in Kibaale District, said he invested more than Shs1m in his four-acre maize farm at the start of the season.

He harvested 28 sacks, earning about Shs1.26 million instead of the more than Shs3 million he had expected. Mr Birungi said he was unable to raise enough money to pay school fees for his children. He now plans to switch to beans, saying their prices are more stable.

Mr Businge Byamukama, a resident of Kijungu Village in Kagadi District, shared a similar experience. He spent nearly Shs900,000 on labour and farm inputs for his two-acre maize garden but harvested only 27 sacks.

Mr Byamukama was forced to sell each kilogramme at Shs250, far below what he had hoped, earning just Shs1 million. He said from the little he earned, he had to clear a Shs300,000 loan, pay Shs200,000 in school fees, and settle hospital bills of Shs100,000.

What remained, he said, was hardly enough to take care of his family.

“I was forced to sell because I couldn’t afford storage. I am now planning to intercrop next season because relying on just one crop isn’t sustainable. I want to switch to beans,” he explained.

Mr Zimwanguhiiza Byaruhanga, a farmer from Kibaale District, said he invested about Shs800,000 in labour, pesticides, fertilisers, and seeds for his two-acre garden. He had expected at least 20 sacks but ended up with only 16.

“What we put in doesn’t match what we got out. We’ve been neglected, yet agriculture is a major contributor to the country’s economy. Why doesn’t the government set regulations to fix prices for farmers? We’re making losses on some of the money we invest, including bank and Sacco loans, and now we’re finding it hard to pay them back,” he said.

He said he had hoped to sell his maize at Shs1,000 per kilogramme, but the market only offered Shs500. Mr Byaruhanga accused middlemen of exploiting farmers by setting unfair prices during harvest time and urged government to step in and regulate the market. ‘

“Even after harvest, the middlemen manipulate measuring tapes to cheat us. But we have no choice—we must sell to support our families, pay loans, and school fees,” he said.

Source: Monitor

A smallholder tomato farmer in the northwestern Uganda region of West Nile sprays his half-acre tomato garden without adequate protection. Many farmers around the country interact with hazardous agro-chemicals without using adequate PPEs. COURTESY PHOTO/SASAKAWA AFRICA ASSOCIATION.

A consortium of civil society organisations (CSOs) has in a Jan.05 statement shown concern about the continued wrong use of dangerous pesticides in the country.

Members of the concerned CSOs mainly work to promote sustainable agricultural trade, food safety and sovereignty, climate justice, biodiversity restoration, and human and environmental rights.

The activists say there are growing concerns about pesticide misuse, including improper application and storage, counterfeit products, insufficient training in use, and use of poorly maintained or totally inadequate spraying equipment.

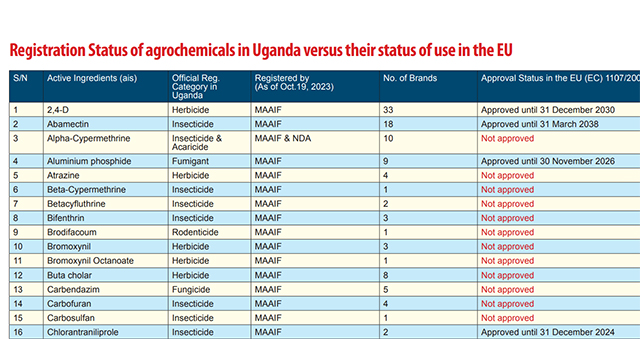

The activists insist the agriculture ministry should deregister at least 55 agro-chemicals that it registered in 2023 well-knowing that the same pesticides, herbicides and insecticides are banned by the European Union, a major market of Uganda’s agricultural produce.

Glyphosate-based herbicides, in particular, have raised significant alarm due to their potential environmental and health risks. Globally, they have been linked to contamination of water sources, soil degradation, and potential carcinogenic effects on humans.

In Uganda, glyphosate which appears in brands such as Rounduo and Weed Master, is widely used, especially among large-scale commercial farms and in weed control.

Betty Rose Aguti, the Policy and Advocacy Specialist at Caritas-Uganda who also doubles as the National Coordinator of Uganda Farmers Common Voice Platform says Uganda’s smallholder farmers need to be guided on the danger posed by some agro-chemicals.

“No one is guiding them on what to do with the agro-chemicals. Nobody is telling the farmers which agro-chemicals to use in what type of soils or on which type of crops and thereafter, what period of time they should take before they harvest.

“We have scenarios where some of these farmers apply these agro-chemicals bare-chested with no face masks and other protective gear; these farmers are using agro-chemicals as though they are using ordinary water.”

“They spray their gardens as they converse with their children and wives. In the course of doing this, they are inhaling the chemicals and after some time, they fall victim to the toxicity of these agro-chemicals and end up flooding the Uganda Cancer Institute,” she says.

What are pesticides?

Pesticides are defined by UN agencies; the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO), as substances or mixture of substances of chemicals or biological ingredients intended for repelling, destroying or controlling any pest, or regulating plant growth.

These often include ingredients that modify pest behaviour or their physiology (insect repellents) or affect crops during production or storage (herbicide safeners and synergists, germination inhibitors), as well as insecticides, fungicides and herbicides.

However, according to the activists, most of the chemicals on the Ugandan market are quite hazardous to both human health and the environment and yet they continue being used inappropriately by Ugandan smallholder farmers.

“We call upon the government of Uganda to regulate and ban all hazardous pesticides especially glyphosate and chlorpyriphos on the market in Uganda,” said Jane Nalunga, the Executive Director of the Uganda chapter of the Southern and Eastern Africa Trade Information and Negotiations Institute (SEATINI), a regional NGO that promotes pro-development trade, fiscal and investment-related poicies and processes.

Backbone of Uganda’s economy

The activists say Uganda’s agriculture sector is the mainstay of Uganda’s economy as it remains the main source of food, raw materials for industries, and employment of about 70% of Ugandans. The sector contributes about 24% to the country’s GDP.

“We cannot allow people with intellectual dishonesty to continue playing with the sector,” one of the activists said on Jan.5 during a press conference at the SEATINI-Uganda headquarters in Kampala. “We are aware that pesticides are significantly impacting health, biodiversity, socio-economic well-being, trade, and food security,” added Nalunga.

According to a 2020 World Health Organisation report, about 385 million cases of unintentional pesticide poisoning, including 11,000 deaths, mostly in low- and middle-income countries such as Uganda, are registered annually worldwide. According to UNICEF, pregnant and breastfeeding mothers, children under the age of five and the elderly are the most vulnerable to the effects of pesticides.

The activists say increased use of highly hazardous pesticides in Uganda is a threat to the right to adequate food, people’s livelihoods and farmers’ rights. They say pesticide runoff is reducing aquatic species diversity by 42% and threatening pollinators like bees. These insects are particularly critical for 75% of global crop production.

According to the European Environmental Agency, pesticides are intrinsically harmful to living organisms. When used outdoors, they can impact ecosystems even when they are intended to exclusively target a specific pest.

Herbert Kafeero, the Programme Manager at SEATINI-Uganda says the use of hazardous pesticides also has implications for trade. He says, in 2015, the government of Uganda imposed a self-ban on the export of agricultural produce to the EU because agro-chemical residues had been found in Uganda’s agricultural produce. “The self-ban was meant to address the challenges that were cited by the EU,” he says, “So we cannot ignore the fact that hazardous pesticides negatively impact the country’s trade and food security.”

He says, at the time, the government committed to retrain farmers and exporters to the EU regarding the EU’s sanitary and phytosanitary standards. Kafeero says the government must find solutions to the mushrooming agro-chemical dealers on the market.

“In every trading centre, you will not miss finding an agro-chemical shop and the person operating that agro-chemical shop presents himself as an expert when they actually are not.”

The activists want the Agricultural Chemicals Control Board under the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries to quickly profile the various agrochemicals, acaricides and inputs and their various sources that are available on the market in Uganda and ban the highly hazardous ones.

They also want the Department of Crop Inspection and Certification at the agriculture ministry to strengthen the regulation, management, use, handling, storage and trade of agrochemicals in the country.

They also want the government and other stakeholders to purposively plan and budget for education and awareness on the management, use, handling, storage and trade of agrochemicals in Uganda.

Prof. Ogenga Latigo disagrees

The activists were infact responding to Morris Ogenga Latigo, a Ugandan professor of entomology (study of insects) who had written an opinion on December 31, 2024, downplaying civil society’s concerns about hazardous pesticide and insecticide use in Uganda.

Prof. Ogenga Latigo in his article said the issue of agro-chemical use on farm pests and weeds and households was being exaggerated by civil society. He said the targeted agro-chemical inputs (pesticides, insecticides and herbicides) were being used in other countries.

The acrimonious debate has since sucked in the agricuture ministry. Stephen Byantware, the Director in charge of Crop Protection at the agriculture ministry told the media in Kampala recently that Uganda has an Agriculture Police Force and a Department of Inspection and Certification of agriculture inputs that “ensure that only nationally and globally approved agro-chemicals enter the Ugandan market.”

“The chemicals allowed into the country are those that have been approved,” he said, “There are no banned products on sale in Uganda. You cannot find DDT or Endosulfan in Uganda.”

But David Kabanda, the Executive Director of the Centre for Food and Adequate Living Rights, a Kampala-based non-profit, says Ugandans should know that hazardous pesticides have become one of the “loudest killers” and yet Ugandan smallholder farmers continue to associate with these chemicals on the farms, in the food stores, and in the homes.

“It’s only in Uganda where we don’t have a farmgate policy and yet we have scientific reports that have pointed out that the food we buy in markets in Kampala is contaminated.” “Don’t we see tomatoes and broccoli full of Mancozeb fungicide yet this chemical has been banned everywhere including the EU?”

“Pesticides are silent killers of humans, of nature, of our soils that are getting barren, of our water, of our agri-food system. I don’t imagine an agri-food system in Uganda without bees, without butterflies, and above all, without grasshoppers,” said Agnes Kirabo, the Executive Director of Food Rights Alliance (FRA).

Desperate smallholder farmers

According to the activists, Uganda’s agriculture system is by default largely organic but in recent years, pest and disease management has become one of the major production constraints for the country’s millions of subsistence farmers. And in recent years, farmers have turned to pesticides to control the pests.

According to the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations, the number of agricultural pesticides used in Uganda doubled in 12 years (2010 – 2022) from 2,990.23 tonnes to 6,009.78 tonnes.

Similarly, the monetary value of pesticides imported to Uganda more than doubled from US$ 32.57 million to US$75.87 million in 2022 with a peak import value of US$108.57 million reported in 2020. The lucrative agro-chemical business has attracted more than 40 registered pesticide importing companies in the country.

The activists say the increased use of pesticides is attributed to their use for weeding and the increased use of hybrid seeds and livestock. According to the CSOs, equally alarming is that many of these pesticides are “synthetic pesticides” which are persistent organic chemicals.

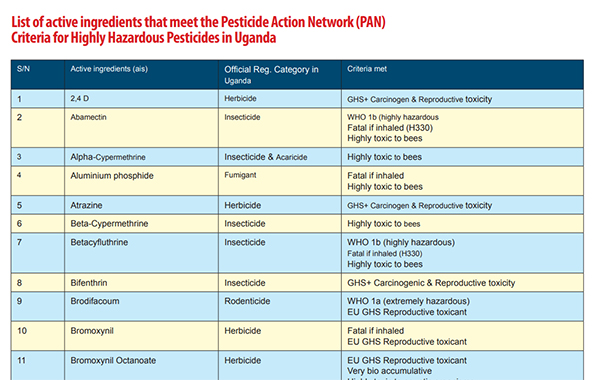

A study published last year by the Food Safety Coalition Uganda (FoSCU) titled: ‘‘Food Safety-Crop Protection Nexus: Insights from the Uganda’s agriculture sector,’’ noted that of the legally registered active ingredients, 47.8% (of the active ingredients) and 68.6% of the brands in Uganda qualified as “Highly Hazardous Pesticides.”

Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs) are classified as “reproductive toxicants” meaning they potentially can negatively affect the human reproductive system and have adverse effects on pregnancy outcomes and reduced fertility.

The same study noted that 15.6% of the registered active ingredients and 19.2% of the registered brands in Uganda qualified as highly hazardous pesticides in accordance with the FAO/WHO-Joint Meeting on Pesticide Management (JMPM) criteria.

According to the activists, by July 2023, over 65% of the 55 flagged active ingredients registered for use in Uganda and yet considered as highly hazardous pesticides according to the Pesticide Action Network (PAN) criteria, were not approved for use in the European Union economic bloc.

The majority (49%) of these pesticides are highly toxic to bees, 20% are carcinogenic and reproductive toxicants while 18% are probable carcinogens, and 9% are highly persistent in water and soil and are highly toxic to aquatic organisms.

They say that, based on the Uganda agrochemical register at the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF) and the National Drug Authority (NDA), the country had at least 115 active ingredients and 669 brands of synthetic pesticides legally registered for use in Uganda by the end of 2023.

“These are presenting in 459 brands, but all these active ingredients in the 459 brands, according to the PAN, are classified as highly hazardous,” said Bernard Bwambale, the head of programmes at the Global Consumer Centre, or CONSENT, who also coordinates the activities on food safety at the Food Safety Coalition of Uganda.

If it is hazardous in EU, it is hazardous in Uganda

Bwambale says his organisation has found that of the 55 active ingredients registered in Uganda, 65.5% of them cannot be used in their countries of origin. “Now, if a chemical, a highly hazardous chemical, is produced in a particular country and that country cannot use it, who are we to start thinking that we can use it? This is where our concern is.”

“So, whatever is not used in the EU, it means it’s not fit for use for human beings. The human beings in Uganda and the human beings in Europe are all human beings. And we are all sharing the same human rights.” He says some of the highly hazardous pesticides are mutagenic, meaning they can alter one’s DNA or genetic make-up.

“Literally, it would mean that when you consume food consisting of this kind of product, you stand a risk of your DNA or your genetic makeup being altered. And that is why some research is pointing to some of these chemicals being responsible for birth defects.” He says other chemicals are carcinogenic, meaning the chemical has the potential to cause cancer.

But Prof. Ogenga Latigo says some chemicals like Mancozeb the civil society claim are carcinogenic are not. He describes others as ‘probable carcinogens.’ A probable carcinogen is a substance that has a strong but not conclusive amount of evidence that it can cause cancer in humans.

But Bwambale says, “They don’t want people to keep confusing us with science.” He says other chemicals have been considered fatal when inhaled. “Imagine a farmer who doesn’t know these things and is spraying but is carrying a baby. So both the mother and the baby are inhaling this chemical,” he says, “We need to regulate these chemicals as much as we can.”

He says recent studies have indicated that some of these chemicals were found in human bodies –in sweat, urine and blood, in food and in water. “When the Europeans send us, for instance, these chemicals and we buy them, they also have regulations on which kind of food we can sell to them. We all know that.”

He says when farmers use these chemicals in the name of commercialising agriculture, they may produce very big tomatoes that do not rot, for example, but they cannot sell them beyond Uganda.

“You cannot put them on the EU market because they don’t meet the standard of the EU market. So they (agriculture products still remain with us,” he says.

Source: The independent

UPDF General on the spot over fresh evictions in Hoima

Small-scale fishers and coastal communities are pushing to testify before a human rights commission investigating the causes of food inequality in South Africa.

The Kenyan government insists on maintaining provisions of the Seed Act that the court nullified: farmers and legal experts question the motive.

FEATURE: What Lagos Can Learn From Kenya, Morocco, Uganda’s Forced Evictions

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Evicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks agoUS-DRC Strategic Partnership Agreement Faces Constitutional Challenge in Court

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoClose to six years on, Pangero Chiefdom subjects still linger in pain after the government army’s forceful takeover of their ancestral land.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoIndigenous communities’ complaint against World Bank-linked Nepal Cable Car Project declared eligible for investigation.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoDecades of land loss and chronic poverty: Salala Rubber Plantation prioritizes profit over the well-being of local Liberian communities.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoThe Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network Joint Radio program boosts Farmers’ knowledge of seed and food sovereignty.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days agoFEATURE: What Lagos Can Learn From Kenya, Morocco, Uganda’s Forced Evictions

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago13 years after the refugee host community was forcefully evicted to expand a refugee settlement, thousands remain unsettled.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day agoSmall-scale fishers and coastal communities are pushing to testify before a human rights commission investigating the causes of food inequality in South Africa.