By Witness Radio team.

Mr. Francis Njiri, a small-scale farmer from Makongo and a member of the Seed Savers Network Kenya, questions the spirit behind the Kenyan government and the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service (KEPHIS) in appealing against the recent High Court ruling on seed rights, including saving and exchange.

The landmark judgment delivered in November 2025 declared key sections of the Seed and Plant Varieties Act unconstitutional, directly affirming farmers’ rights to save, share, and exchange seeds outside formal systems, which many smallholder farmers like Mr. Njiri see as a victory for traditional practices and their livelihoods.

15 smallholder farmers from the Seed Savers Network filed a constitutional petition in 2022, claiming that Kenya’s Seeds and Plant Varieties Act (SPVA) and the Seeds and Plant Varieties (Seeds) Regulations, 2016, have restrictive provisions that violate fundamental rights protected by Kenya’s Constitution, which the Kenya’s High Court in Machakos ruled in their favor.

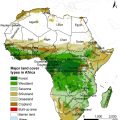

According to court documents seen by Witness Radio, the Kenyan government and KEPHIS have appealedagainst the court ruling, claiming that the High Court judge misinterpreted key legal provisions, underscoring the ongoing legal battle over seed rights.

“Take notice that The Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service and The Attorney General, the above-named Appellants, appeal to the Court of Appeal against the whole of the above-mentioned decision,” documents seen by Witness Radio reveal.

“The Learned Judge erred in law and in fact by misinterpreting and conflating Sections 8(1) and 8A of the Seeds and Plant Varieties Act with Article 11(3)(b) of the Constitution, and by wrongly concluding that those provisions limit or undermine Section 27A, while in fact Sections 8(1), 8A and 27A operate harmoniously to give full effect to Article 11(3)(b) of the Constitution.

The Learned Judge erred in law and in fact by holding that Sections 8(1) and 10(4)(c), (d), (e), (f) and (g) of the Seeds and Plant Varieties Act, together with Regulations 6, 16 and 19 of the Seed and Plant Varieties (Seed) Regulations are unconstitutional based on discrimination under Article 27(2) of the Constitution, when no distinction had been demonstrated…” further reveals.

The government’s decision to appeal has alarmed farming communities and civil society, raising fears that their interests are being overlooked.

“I don’t think the government is working in the interests of farmers. We suspect these actions serve multinational corporations’ interests because farmers were not consulted in the first place.” Mr. Njiri says.

Mr. Njiri, who has practiced agroecological farming for years, is one of the petitioners in the case. Alongside other farmers from across the country, he challenged the constitutionality of provisions that restricted the use of farm-saved seeds. He argues that such laws disproportionately favored commercial seed companies while undermining indigenous seed systems that have sustained communities for generations.

According to him, the lack of consultation with smallholder farmers, who constitute the majority of Kenya’s agricultural producers, raises serious questions about whose interests are being prioritized.

For generations, farmers have saved, exchanged, and improved seeds-these practices are part of our heritage and vital for our survival. Decisions about seeds should involve those who depend on them most.

In the case that had been determined in favor of the local farmers, Advocate Wambugu Wanjohi says the Government of Kenya and KEPHIS were challenging mostly seed sovereignty, the right to save, share, and replant seeds, and the right to participate in seed policies.

“Now, the Seed and Plant Varieties Amendment Act aligned Kenya with UPOV of 1991, and seed exchange outside the normal certification process became illegal. And the consequence was that the government pushed indigenous seed systems underground.” He mentioned.

Wanjohi describes the High Court ruling as a constitutional milestone.

“This case was not simply about regulatory compliance. The Court approached it as a human rights matter. It examined whether criminalizing seed sharing unjustifiably limited constitutional rights such as the right to food, the protection of culture, equality, and fair administrative action,” he said.

“We argued on a constitutional basis. The farmers sought to have these sections declared unconstitutional because the Act and regulations unjustifiably limited the right to food and eroded cultural rights and equality.”

According to Wanjohi, the Court found that the impugned provisions disproportionately burdened smallholder farmers while privileging commercial seed interests.

“The Constitution does not permit legislation that effectively punishes the survival practices of small-scale farmers. The judgment reaffirmed that seed governance must align with constitutional protections,” he added.

Dr. David Kabanda, Director of the Center for Food and Adequate Living Rights in Uganda, views the ruling as significant beyond Kenya’s borders.

“Seed is not merely a commercial commodity; it is the foundation of food systems and community resilience. When laws shift control of seed away from farmers without meaningful participation, they raise fundamental legal and human rights questions,” Kabanda says.

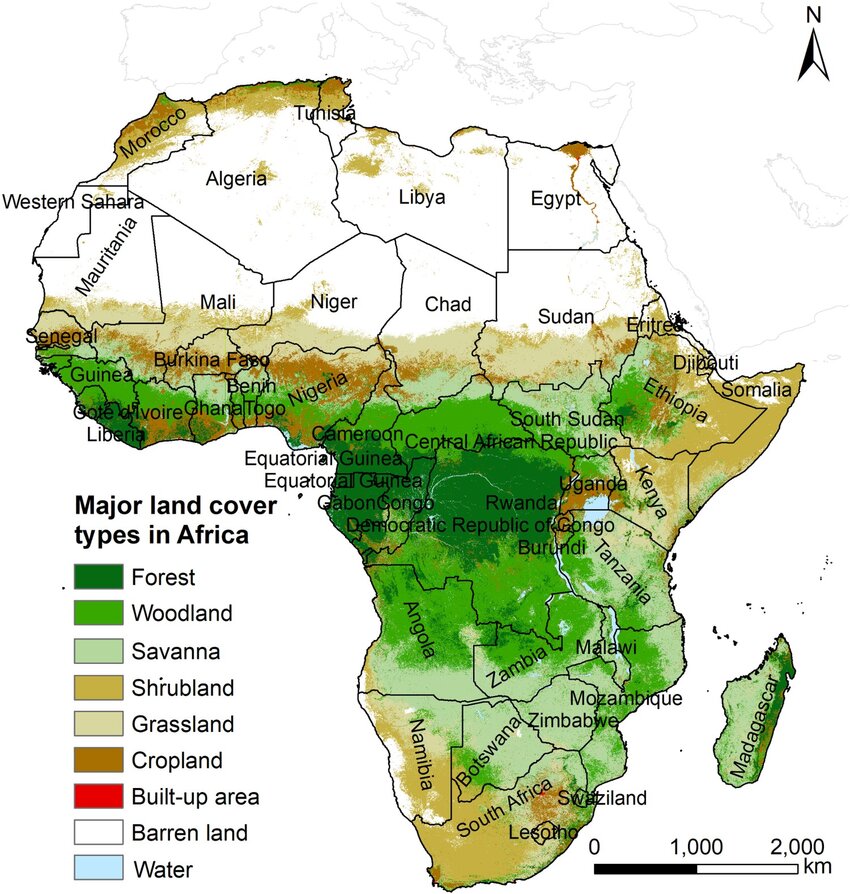

He adds that the case introduces a constitutional perspective that could influence similar debates across East Africa, particularly in countries aligning seed laws with international intellectual property standards.

“Seed determines protection of our land, because in an ordinary African city, if you don’t have seed, then you cannot plant. Seed and food give land relevance in many communities. So, if someone takes our seed from you, especially in the current region where some countries, like Kenya, want to create what they call seed merchants and impose exorbitant fees on you to operate the seed trade or business, it is alienating people from the livelihood they should have. Because if any state or multinational takes away the seed, the propagating material, whether for food or agriculture, it is touching the nerve of your existence.” Kabanda added.

As the appeal process unfolds, farmers like Mr. Njiri say they remain committed to defending what they consider fundamental rights: the right to seed, the right to food, and the right to participate in decisions that directly affect their livelihoods.

“We will continue to stand firm. Seeds are our life. Without them, there is no farming, and without farming, there is no food. We will fight and fight and fight until we win. And we believe we shall win the entire battle. Because we wouldn’t let that freedom, which God gives, be taken away from us because someone wants to protect their interests or farmers’ interests,” he concluded.

With the government and KEPHIS appealing the High Court’s landmark decision, it is now more important than ever for judges, lawyers, and civil society across Africa to actively support farmers in defending their constitutional seed rights. “Strategic litigation has set a precedent on the continent, showing that courts can and must uphold food sovereignty and protect the rights of smallholder farmers.” Advocate Wanjohi added.

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day ago