SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

US government stops funding to WWF, WCS and other conservation organisations because of human rights abuses

Published

5 years agoon

By Chris Lang

In autumn 2019, the US government suspended US$12.3 million of funding to the Central Africa Regional Program for the Environment (CARPE). This followed a bipartisan congressional oversight investigation to examine whether US conservation funds were supporting eco-guards who committed human rights abuses.

CARPE is funded by money from the US Agency for International Development (USAID) transferred to the US Fish and Widlife Service (FWS).

The review of US conservation funding followed the year long investigation by BuzzFeed News into human rights abuses and WWF. The investigation was published in March 2019 and revealed that WWF had funded eco-guards who tortured and killed people.

Conservation organisations responses: “Not uniformly thorough or responsible”

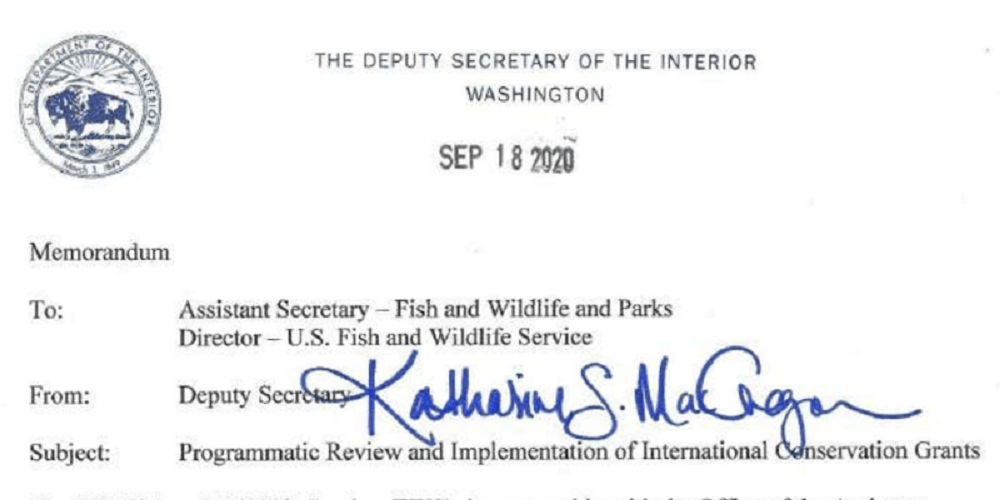

In November 2019, the FWS sent an information request to some of the organisations that had received CARPE funding. A memo dated 18 September 2020 from Katherin MacGregor, the US Deputy Secretary of the Interior, states that,

While all grantees replied, the responses were not uniformly thorough or responsible, thereby raising further questions about the desire and capability of grantees and the ability of the FWS to adequately monitor allegations and prevent such abuses in the future. One organization, Virunga Foundation, replied with a statement that it would be closing down its operations in 2019, and would not be sending any further documentation.

Wildlife Conservation Society replied “stating that the Service’s request was overly burdensome and that they would only be able to produce a limited amount of information based on their internal document retention policy,” MacGregor writes. Meanwhile African Parks told the FWS that “three investigations into allegations of human rights violations were conducted in 2019 managed by the organization and closed without documented consultation or notice provided to the Service prior to this data call.”

Last week, Survival International put out a summary of the highlights of the Department of Interior’s memo, under the headline: “Atrocities prompt US authorities to halt funding to WWF, WCS in major blow to conservation industry”.

The following are REDD-Monitor’s notes of some of the key points of the memo.

US Government Accountability Office investigation

In late 2019, the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) also started an investigation into the same issue. In August 2020, the Department of the Interior received a draft of GAO’s report.

In her memo MacGregor writes that the draft report “contained no recommendations and instead indicated that GAO could not properly perform an inquiry into the in-country monitoring component of the CARPE program – arguably one of the areas of greatest concern and vulnerability when reviewing real-time oversight controls – due to COVID-19 travel restrictions.”

Nevertheless, GAO’s report included “some interesting findings”, MacGregor writes:

For instance, interviews with U.S. government officials at multiple relevant agencies (State, USAID, and FWS) indicated widespread surprise by the allegations and concer that they were not notified previously through standard channels.

The State Department has relied on partner organisations, including WWF, to carry out its own internal investigation to determine whether US government-funded organisations were involved in human rights abuses. MacGregor writes,

The notion of an agency relying on an awardee to investigate itself to determine wrongdoing was highlighted during a Department briefing to House Natural Resources Committee staff conducted in July 2019. Staff from both the majority and minority expressed concern with this practice.

MacGregor notes that the review found that “information remains quite dispersed, buried in emails of former employees, spread across different Federal agencies, and in many instances, in the possession of awardees who have provided information in rolling productions that have not always been completed in a timely manner.” She adds in a footnote that,

WWF stated they were told by other federal parties not to provide internal reports that document findings of wrongdoing by auditors they hired to investigate long-standing allegations. Fortunately, these documents were ultimately made available to the Department and contributed to our analysis.

The reprehensible nature of the abuse

MacGregor writes that,

[I]t is important to make clear the reprehensible nature of the abuse that has been documented and must be guarded against in the future:

- Four women were beaten with a baton, lashed on their backs and legs, and raped by the eco-guards – two of the women were pregnant, and were still raped, even though a woman “begged them to spare her.”

- Three men were held by eco-guards for three days, during which the eco-guards beat them, “tied their penises with fishing thread, and hung them at the branch of a tree.”

- Eco-guards were falsely informed that a farmer’s family was in possession of a weapon, so in the middle of the night the eco-guards burst into the farmer’s home, beat all the members of the household, raped his wife in the bushes, and imprisoned the farmer and his father.

- A woman was detained by guards, forced to cook for and serve the guards, and was tortured for four days after guards were falsely informed that her husband was in possession of a weapon of war. She was only released when her husband found her and took her place. He was imprisoned without a trial.

These abuses of human rights are from reports commissioned by conservation organisations themselves. The first, second, and fourth in the list are from a report commissioned by WWF to investigate human rights abuses in the Salonga National Park. REDD-Monitor wrote about these abuses and WWF’s failure to make the report public, here:

UNDP’s draft investigative report

MacGregor also refers to UNDP’s 2020 draft investigative report that confirms that WWF-funded eco-guards beat up indigenous peoples in the Republic of Congo. MacGregor writes:

- Reports of abuse of indigenous populations were ignored for several years by WWF and initially UNDP staff, until being investigated following a formal complaint submitted by Survival International in July 2018.

- “These beatings occur when the Baka are in their camps along the road as well as when they are in the forest. They affect men, women, and children. … There are reports of Baka men having been taken to prison and of torture and rape inside prison. The widow of one Baka man spoke about her husband being so ill-treated in prison that he died shortly after his release. He had been transported to prison in a WWF-marked vehicle.“

- WWF staff in Congo “acknowledged the evidence of abuse against the Baku” by the eco-guards … but appeared to view them as isolated incidents.

REDD-Monitor wrote about the draft UNDP report in February 2020:

WWF used funds to pay for firearms and ammunition

A 2019 internal WWF report about the proposed Messok Dja Protected Area in the Republic of Congo, written by the Forest Peoples Programme, states that by continuing to work with or supporting governments that fail to protect human rights, WWF was “contributing to human rights violations, in contravention of its own policies and of international law.”

WWF submitted materials to the Department of Interior that “even appear to imply that the organization used funds to support potentially prohibited activity, including paying for firearms and ammunition,” MacGregor writes. She adds that, “The same document contained statements that implied future FWS funds would continue to be leveraged for the effort’s biggest perceived need – firearms and ammunition.”

The reports investigating human rights abuses that have been commissioned by the conservation organisations are internal – they are not made available publicly, or even to the US government. MacGregor writes that,

As evidenced in this programmatic review, allegations of human rights abuse have been consistently handled internally by awardees, even when those allegations implicate the organization’s employees and taxpayer funding. Subsequent investigations resulted in findings of misconduct, but were then relayed to the organization in confidential reports and not made available to the U.S. Government either at all or in a timely manner.

Proposals on future conservation funding

MacGregor’s memo includes proposals to avoid funding “where the FWS cannot ensure future human rights violations will not occur.”

These include the following:

- Free, informed, and prior consent by the indigenous population must be obtained before a program is established or expanded, with approriate criteria developed to document the engagement and corresponding consent.

- To the extent consistent with all legal obligations or to mitigate risks associated with particular programs and/or recipients, the FWS will no longer provide funding for subgrantees.

- The FWS will not award grants to conduct high-risk activities such as eco-guards, law enforcement activities and supplies, community patrols, and other similar or related activities. This includes activities related to relocating communities, voluntarily or involuntarily, either through direct engagement or support to local government entities seeking to do the same.

- Grant awardees will certify that no activities will be conducted in violation of U.S. law, rules or regulations and that they are taking steps to protect human rights during the implementation of the grant.

- Consistent with applicable laws, impost minimum bonding and/or insurance requirements for the purposes of addressing harm or liability resulting from actual or potential human rights violations and other risks related to activities or operations in which such violations are possible. (FWS shall work with SOL to advise on maximum bond and insurance amounts authorized under the law).

- Grantees will provide for a whistleblower capability to both alert the FWS of potential human rights abuses and ensure thorough investigation of such allegations.

- Awardees will satisfy appropriate reporting requirements, including mandating immediate notification of any internal investigations conducted on human rights abuses in which federal dollars may have been involved.

Original Post: Redd Monitor

Related posts:

WWF apologises for human rights abuse allegations and commits to an indigenous-led approach to global conservation

WWF apologises for human rights abuse allegations and commits to an indigenous-led approach to global conservation

Call to Sever Ties with Tanzanian Government Over Latest Human Rights Abuses Against the Maasai

Call to Sever Ties with Tanzanian Government Over Latest Human Rights Abuses Against the Maasai

Expeditiously investigate land grabbing and related human rights abuses in Mubende District

Expeditiously investigate land grabbing and related human rights abuses in Mubende District

Times for mitr phol, coca cola, nestle, mars wrigley and bonsucro to live up to their human rights responsibilities.

Times for mitr phol, coca cola, nestle, mars wrigley and bonsucro to live up to their human rights responsibilities.

You may like

-

Floods leave gardens bare in eastern region

-

After being tortured by the army, the land rights defender is charged and remanded to prison

-

A government project is pushing hundreds of families off the land without re-settlement

-

2,000 Karimojong flee to Teso in search for food

-

Biden lists US plans for Africa

-

Sexual exploitation and violence against women at the root of the industrial plantation model

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Seizing the Jubilee moment: Cancel the debt to unlock Africa’s clean energy future

Published

1 day agoon

July 12, 2025

Africa has the resources and the vision for a just energy transition, but it is trapped in a financial system structured to take more than it gives. In this blog, we outline how debt burdens and climate impacts are holding the continent back, and looks at the role of institutions that shape the global financial order, like the World Bank, African Development Bank and IMF. As these institutions and governments meet in Seville for FfD4, we urge them to heed people’s calls for reform: cancel the debt, redistribute the wealth, and fund the just transition. — By Rajneesh Bhuee and Lola Allen

With 60% of the world’s best solar energy resources and 70% of the cobalt essential for electric vehicle batteries, the African continent has everything it needs to power its development and become a global reference point for sustainable energy production. That potential, however, remains largely untapped; Africa receives just 2% of global renewable energy investment. As the UNCTAD Secretary-General Rebeca Grynspan warns, too many countries are forced to “default on their development to avoid defaulting on their debt.”

The cost of servicing unsustainable debts, layered with new loan-based climate and development finance, leaves governments with little fiscal space to invest in clean energy, health or education. In 2022 alone, African countries spent more than $100 billion on debt servicing, over twice what they spent on health or education. Add to this the $90 billion lost annually to illicit financial flows, and the reality is stark: more money leaves the continent through financial leakages (also including unfair trade and extractive investment) than comes in through productive, equitable and development-oriented finance.

These are not isolated problems. They reflect a financial system that has been built to serve global markets rather than people. Between 2020 and 2025, four African countries defaulted on their external debts, that is, they failed to make scheduled repayments to creditors like the International Monetary Fund or bondholders, triggering fiscal crises and, in several cases, IMF interventions tied to austerity measures. Pope Francis’ Jubilee Report (2025) and hundreds of civil society groups argue that these defaults reflect the deeper crisis of unsustainable debt. Meanwhile, 24 more African countries are now in or near debt distress. None have successfully restructured their debts under the G20 Common Framework, a mechanism launched in 2020 to facilitate debt relief among public and private creditors. The Framework has been widely criticised for being slow, opaque and ineffective. According to Eurodad, without urgent systemic reforms, up to 47 Global South countries, home to over 1.1 billion people, face insolvency risks within five years if they attempt to meet climate and development goals.

How debt undermines the just energy transition

Debt has become both a driver and a symptom of climate injustice. Countries that did the least to cause the climate crisis now pay the highest price, twice over. First, they suffer the impacts. Second, they must borrow to rebuild.

This is happening just as concessional finance disappears. The US has withdrawn from the African Development Fund’s concessional window (worth $550m), yet maintains influence over private-sector lending. It has also opted out of the UN Financing for Development Conference (FfD4), a historic opportunity to confront the injustice of our financial system. Meanwhile, European governments, though now celebrating themselves as defenders of multilateralism, played a key role in weakening the outcome of FfD4, slashing aid budgets, redirecting funds toward militarisation, and systematically blocking proposals for a UN-led sovereign debt workout mechanism. With rising insecurity and geopolitical tensions, these actions send a troubling signal: at a moment when global cooperation is urgently needed, many Global North countries are stepping back from efforts to fix the very system that is preventing climate justice and clean energy for much of the Global South.

A role for the AfDB?

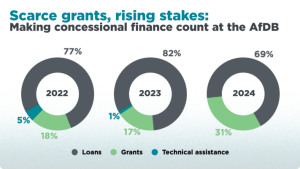

The African Development Bank (AfDB), under incoming president Sidi Ould Tah , has made progressive commitments of $10 billion to climate-resilient infrastructure and $4 billion to clean cooking. Between 2022 and 2024, one in five (20%) of its energy dollars were grants, far exceeding The World Bank ‘s 10% and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) ‘s 3.8%. The AfDB has also backed systemic reform: for example, calling for Special Drawing Rights (SDR) redistribution, launching an African Financial Stability Mechanism that could save up to $20 billion in debt servicing, and consistently advocating for fairer lending terms.

Yet, even progressive leadership struggles within a broken system. Recourse’s recent research shows that AfDB energy finance dropped 67% in 2024, from $992.7 million to just $329.6 million. Of this, a staggering 73% went to large-scale infrastructure like mega hydro dams and export-focused transmission lines, ‘false solutions’ that bypass the energy-poor and displace communities. Meanwhile, support for locally-appropriate, decentralised renewable energy systems such as mini-grids, solar appliances, and clean cookstoves plummeted by over 90%, from $694.5 million to just $61 million, with only five of 13 projects directly addressing energy access in 2024.

Africa received just 2.8% of global climate finance in 2021–22, and what is labelled as “climate finance” is often little more than a Trojan horse: resource-backed loans, debt-for-nature swaps, and blended finance instruments that shift risk to the public while offering little real benefit to local communities. These mechanisms, promoted as “innovative” or “green”, often entrench financial dependency and fail to deliver meaningful change for energy-poor or climate-vulnerable groups.

Meanwhile, initiatives that could build green industry and renewable capacity across Africa are falling short in both scale and speed. Flagship projects, such as the EU’s Global Gateway, have failed to drive green industrialisation in Africa, and carbon markets continue to delay real emissions reductions, subsidise fossil fuel interests, and entrench elite control over land and resources.

Mission 300: Ambition or another missed opportunity?

In this constrained context, the AfDB and World Bank launched Mission 300, an ambitious plan to connect 300 million Africans to electricity by 2030. Pragmatic goals like electrification are crucial, but the story beneath the surface of Mission 300 raises concern. Far from serving households, many projects under the initiative appear more aligned with export markets and large-scale energy users, echoing decades of infrastructure that bypasses those most in need.

Mission 300 can still be transformative, but only if it centres people, not profits. Energy access must begin with those who need it most: women and youth, especially in rural communities. Across Africa, many women cook over open fires, walk hours to gather fuel, and care for families in homes without light or clean air. This is not just an inconvenience, it is structural violence and policy failure.

Yet most energy finance still flows to centralised grids, mega-projects, and sometimes fossil gas (misleadingly called a “transition fuel”). These do little to address energy poverty. Locally appropriate decentralised renewable energy solutions, solar-powered appliances, clean cookstoves, and mini-grids can deliver faster, cheaper, and more equitable impact. Mission 300 must invest in such solutions, without adding to existing debt problems. It should support national policy design, for example, by ensuring that energy policy is responsive to women’s needs, making use of gender-disaggregated data and community consultation.

The Jubilee: A year for action

In a year already marked as a Jubilee moment, African leaders have demanded reform: including a sovereign debt workout mechanism and a UN Tax Convention to end illicit financial flows. Yet as AFRODAD has documented, these demands were blocked at the FfD4 negotiations by wealthy nations—notably the EU and UK—even as climate impacts grow and fiscal space shrinks.

This is not just about finance. It is about reclaiming sovereignty. The incoming AfDB president and all the multilateral development banks face a choice: continue financing extractive, large-scale projects that serve foreign interests, or invest in decentralised, gender-responsive, pro-people solutions that shift power and ownership.

Africa has the resources. What it needs is fiscal space, public-led finance, and global rules that prioritise people and planet over profit. The Jubilee call is clear: cancel the debt, redistribute the wealth, and fund the just transition.

Source: Recourse through LinkedIn Account Recourse.

Related posts:

Statement: The Energy Sector Strategy 2024–2028 Must Mark the End of the EBRD’s Support to Fossil Fuels

Statement: The Energy Sector Strategy 2024–2028 Must Mark the End of the EBRD’s Support to Fossil Fuels

African Development Bank decides not to fund Kenya coal project

African Development Bank decides not to fund Kenya coal project

Africa must unlock the power of its women to save climate change

Africa must unlock the power of its women to save climate change

PFZW scraps funding from Total and others for failure to transition into a cleaner energy mix.

PFZW scraps funding from Total and others for failure to transition into a cleaner energy mix.

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

Published

5 days agoon

July 8, 2025

Special report by the dedicated and thorough Witness Radio team, offering a comprehensive and in-depth overview of the situation.

As Uganda moves forward with the controversial East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), a wave of arrests, intimidation, and court cases has targeted youth and environmental activists opposing the project. However, there is a noticeable and encouraging shift within Uganda’s justice systems, with a growing support for the protesters, potentially signaling a change in the legal landscape.

The EACOP project, stretching 1,443 kilometers from Uganda to Tanzania, has been hailed by the government as a development milestone. However, human rights groups and environmental watchdogs have consistently warned that the project poses serious risks to communities, biodiversity, and the climate. Concerns over land grabbing, inadequate compensation, and ecological degradation have mobilized a new generation of Ugandan activists.

Since 2022, as opposition to EACOP grew louder, Ugandan authorities have intensified a campaign of arrests and legal harassment. Police, military, and currently the Special Forces Command, a security unit tasked with protecting Uganda’s president, have been involved in brutal crackdowns on these activists.

Yuda Kaye, the mobilizer for students against EACOP, believes the criminalization is an attempt by the government to weaken their cause and silence them from speaking out about the project’s negative impacts.

“We are arrested just for raising the project concerns, which affect our future, the local communities, and the environment at large. Oftentimes, we are arrested without reason. They just round us up at once and brutally arrest us, Mr. Kaye reveals, in an interview with Witness Radio’s research team.

Activists have faced a litany of charges, including unlawful assembly, incitement to violence, public nuisance, and criminal trespass. Many of these charges have lacked substantive evidence and have been dismissed by the courts or had their files closed by the police after prolonged delays.

A case review conducted by Witness Radio Uganda reveals that Uganda’s justice system is being used to suppress the activities of youth activists opposing the project, rather than convicting them. However, despite the system being used to silence them, it has often found no merit in these cases.

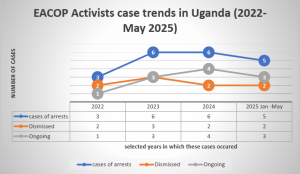

Of a sample of 20 documented cases since 2022 involving the arrest of over 180 activists, 9 case files against the activists have either been dismissed by courts or closed by the police due to a lack of prosecution, another signal indicating the relevance of their work, while 11 cases remain ongoing.

The chart below shows trends in arrests, dismissed cases, and ongoing cases involving EACOP activists in Uganda from 2022 to May 2025.

The review was conducted with support from the activists themselves and their lawyers. It involved a desk review and analysis of Witness Radio articles concerning the arrests of defenders and activists opposing the EACOP project.

Witness Radio’s analysis reveals a concerning trend as the majority of cases involving these activists are stalling at the police level rather than progressing to the courts of law. This suggests that the police have not only criminalized activism but are also playing a syndicate role in deliberately prolonging these cases under the excuse of ongoing investigations.

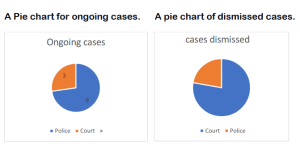

“While both the police and judiciary are being used to suppress dissent, the courts have at least demonstrated a degree of fairness, having dismissed at least 78% of cases that fall within their jurisdiction. In contrast, the police continue to hold 73% of activist cases in limbo, citing investigations as justification for indefinite delays.” The research team discovered.

Witness Radio’s analysis further shows that in most of these cases, the state has failed to produce witnesses or evidence to convict the activists, adding that the charges are often just tools of intimidation. Additionally, this is accompanied by more extended periods during which decisions are being made.

Despite the intense crackdown, it is evident that these activists are winning, as no proven record of sentencing has been observed. Instead, these cases are often marred by delays in court or at the police, and in the end, some have been dismissed. This implies that protest marches and petition deliveries serve a purpose; the state just needs to listen to their concerns and formulate possible solutions to address them,” said Tonny Katende, Witness Radio Uganda’s Research, Media and Documentation Officer.

According to Article 29(1)(d) of the Constitution of Uganda, every individual has the right to “assemble and demonstrate together with others peacefully and unarmed and to petition.” Additionally, Article 20 emphasizes that fundamental rights and freedoms “are inherent and not granted by the State.” Yet activists report that police regularly deny them the right to exercise their rights as guaranteed.

At a February 2025 press conference, EACOP activists strongly condemned the police’s continued unlawful arrests of demonstrators exercising their constitutional rights and case delays. This followed escalating crackdowns that added to the tally of over 100 activists arrested in 2024 alone.

“We strongly condemn these arrests. Detaining demonstrators does not address the concerns affecting grassroots communities impacted by oil and gas projects,” declared the group, led by Bob Barigye, who remains in prison on another charge still linked to his opposition to EACOP.

An interview with Mr. Yuda Kaye, a mobilizer from the Students Against EACOP Movement, confirmed that the ongoing dismissals only reaffirm the legitimacy of their resistance.

“These cases are dismissed because the government and its justice systems don’t have any grounds to convict us. This justifies the fact that the issues we’re discussing are real. We only seek accountability, but since the government has power, they criminalize us and silence us,” Mr. Kaye added.

According to Kaye, the intimidation is real, but so is their commitment. “We are called enemies of progress, but we’re only protecting our future and that of our country. We’ve often proposed alternatives, but the government doesn’t want them.” He re-echoes.

Despite this, activists say their rights are routinely violated. Witness Radio Uganda attempted to contact the police spokesperson, Mr. Kituuma Rusooke, but known numbers were unreachable, and messages sent to him went unanswered.

In a separate interview with Mr. James Eremye Mawanda, the Judiciary Spokesperson, he acknowledged the pattern of dismissals and delays.

“As the Judiciary, we listen to cases, and where there is no evidence to support the case, a decision is made. When a crime is allegedly committed and an individual is brought before the court, the courts upholding the rule of law shall administer justice,” he said.

According to Witness Radio’s analysis, 2025 has seen the most dismissals so far, with six cases concluding, reinforcing the view that criminalization is used more for intimidation than as a means of legal redress. “Whereas the arrests took place in separate years, most of the dismissals have happened in 2025,” the research team further highlighted.

Mr. Brighton Aryampa, the team lead of Youth for Green Communities, one of the organizations that provide legal representation for Stop-EACOP activists, highlighted that the criminalization of Ugandan activists undermines Uganda’s democratic principles of free expression and open discourse.

“The government, in bed with oil corporations Total Energies and CNOOC, is deliberating using legal action against Stop EACOP activists to suppress dissent, free speech, right to peaceful protest, and against public participation. This is tainting Uganda as a country that undermines the democratic principles of free expression and open discourse, as hundreds of Stop EACOP activists have been arrested, charged, and some tried by a competent court. However, no one has been found guilty of the fabricated offense usually slapped on them.” He said in an interview with Witness Radio.

Counsel Aryampa further advised that the practice of powerful companies and businesses blackmailing and corrupting the Ugandan government to develop harmful projects while ignoring all social warnings and human rights abuses must be stopped.

The pressure exerted by these activists, both locally and internationally, has slowed the EACOP project. It has also led to bankers and insurers withdrawing from financing or insuring the project. According to Stop EACOP campaigners, more than 40 international banks and 30 global insurance firms, including Chubb, have distanced themselves from the controversial pipeline project, citing human rights and climate concerns raised by these activists.

Meanwhile, as the activism grows, the number of arrests is rising. Within just the first six months of 2025, over 40 activists have been criminalized for their activism. Among them is KCB 11, a group of eleven activists that was arrested at the KCB offices in April 2025. The group has spent over two months on remand, despite their lawyers’ pleas for bail to be granted.

Related posts:

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

EACOP: The trial of 20 environmental activists failed to take off, and now they want the case dismissed for lack of prosecution.

EACOP: The trial of 20 environmental activists failed to take off, and now they want the case dismissed for lack of prosecution.

Milestone: Another case against the EACOP activists is dismissed due to the want of prosecution.

Milestone: Another case against the EACOP activists is dismissed due to the want of prosecution.

The latest: Another group of anti-EACOP activists has been arrested for protesting Stanbic Bank’s financing of the EACOP Project.

The latest: Another group of anti-EACOP activists has been arrested for protesting Stanbic Bank’s financing of the EACOP Project.

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

‘Left to suffer’: Kenyan villagers take on Bamburi Cement over assaults, dog attacks

Published

4 months agoon

March 22, 2025

- The victims are aged between 24 and 60, and one of them has since passed on.

- Many were severely injured and hospitalized following brutal attacks, unlawful detention, and physical assault by Bamburi’s security personnel.

Editor’s note: Read the petition here.

Their hopes for justice seemed to be slipping away after initially taking on a multinational corporation and failing to hold it accountable for the brutal injuries they suffered.

The death of one of their own cast a shadow of despair, making it seem unlikely that they would ever bring the corporation to justice for the crimes they alleged.

However, 11 victims of dog attacks, assaults, and other severe human rights violations are now challenging Bamburi Cement PLC’s role in these abuses in court.

They are represented by the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC), which on January 29, 2025, filed a legal claim before a constitutional court in Kenya, seeking to hold the multinational accountable for the harm suffered by the victims—residents of land parcels in Kwale that Bamburi claims ownership of. KHRC worked with the Kwale Mining Alliance (KMA) to bring this case.

The victims, aged between 24 and 60, include Mohamed Salim Mwakongoa, Ali Said, Abdalla Suleiman, Hamadi Jumadari, Abdalla Mohammed, and Omari Mbwana Bahakanda. Others are Shee Said Mbimbi, Omar Mohamed, Omar Ali Kalendi (deceased), Abdalla Jumadari, and Bakari Nuri Kassim.

Bamburi had hired a private security firm and deployed General Service Unit (GSU) officers to guard three adjoining land parcels, covering approximately 1,400 acres in Denyenye, Kwale. The GSU established a camp on the land, which has historically been accessed by residents who have long used established routes to reach the forest and the Indian Ocean.

For decades, these routes provided them with access to resources such as firewood, crops, and fish, which they relied on for their livelihoods. However, five years ago, when they attempted to collect firewood, harvest crops, and access the ocean through the land, Bamburi accused them of trespassing. The company’s private guards and GSU officers responded with force, setting dogs on them and assaulting them.

Many were severely injured and hospitalized following brutal attacks, unlawful detention, and physical assault by Bamburi’s security personnel. These incidents occurred despite the lack of clearly defined boundaries and the fact that the traditional access routes had never been contested.

According to the petition, GSU officers and private guards inflicted serious injuries by kicking, punching, and beating the victims with batons. Those who were arrested were neither taken to a police station nor charged with any offense. Despite their injuries, they were denied emergency medical care.

These actions were intended to intimidate residents, prevent them from accessing the beach, and suppress any historical claims to the land, the victims tell the court. Local police in Kwale failed to investigate the abuses, visit the crime scenes, or arrest any of the perpetrators, they add.

Now, the victims are seeking compensation for these violations. They have also asked the court to declare that their rights were violated through torture inflicted by Bamburi’s guards and GSU officers. Additionally, they want the court to rule that releasing guard dogs to attack them during arrests constituted an extreme and unlawful use of force.

Source: khrc.or.ke

Related posts:

Breaking: Over 600 attacks against defenders have been recorded in the year 2023 globally- BHRRC report.

Breaking: Over 600 attacks against defenders have been recorded in the year 2023 globally- BHRRC report.

Kaweeri Coffee land grabbing case re-trial resumes as evictees continue to suffer gross human rights violations.

Kaweeri Coffee land grabbing case re-trial resumes as evictees continue to suffer gross human rights violations.

Criminalization of planet, land, and environmental defenders in Uganda is on the increase as 2023 recorded the soaring number of attacks.

Criminalization of planet, land, and environmental defenders in Uganda is on the increase as 2023 recorded the soaring number of attacks.

Local land grabbers evict villagers at night; foreign investors cultivate the same lands the next day

Local land grabbers evict villagers at night; foreign investors cultivate the same lands the next day

Land Grabbing Crisis Escalates in Uganda: Mayiga Urges Citizens to Secure Land Documents

Seizing the Jubilee moment: Cancel the debt to unlock Africa’s clean energy future

Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

A decade of displacement: How Uganda’s Oil refinery victims are dying before realizing justice as EACOP secures financial backing to further significant environmental harm.

Govt launches Central Account for Busuulu to protect tenants from evictions

Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

Top 10 agribusiness giants: corporate concentration in food & farming in 2025

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

- PRESENDIANTIAL DIRECTIVE BANNING ALL LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA

- FROM LAND GRABBERS TO CARBON COWBOYS A NEW SCRAMBLE FOR COMMUNITY LANDS TAKES OFF

- African Faith Leaders Demand Reparations From The Gates Foundation.

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS5 days ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS5 days agoActivism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

-

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks agoCommunities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

-

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS1 day ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS1 day agoSeizing the Jubilee moment: Cancel the debt to unlock Africa’s clean energy future

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day agoLand Grabbing Crisis Escalates in Uganda: Mayiga Urges Citizens to Secure Land Documents