WITNESS RADIO MILESTONES

Harvard’s Foreign Farmland Investment Mess

Published

7 years agoon

The university’s holdings in developing markets have proved to be more trouble than they’re worth.

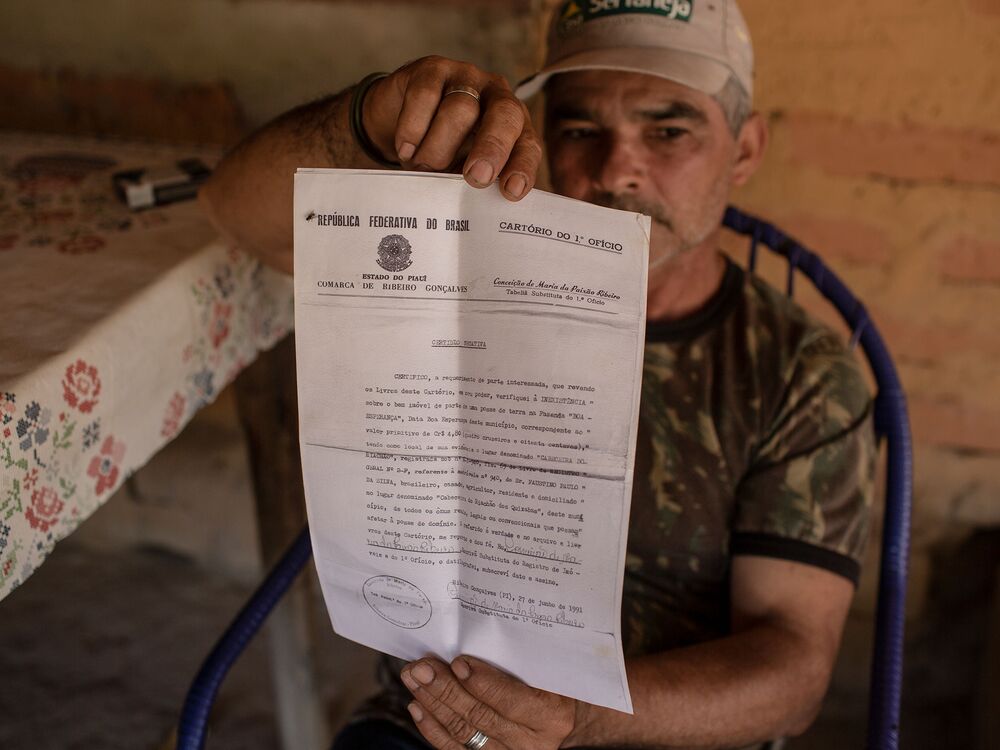

Fourteen years ago, a Brazilian farmer named Ruthardo Grun says he was terrorized by armed thugs who shot at him, burned down his shack, and chased him from land he was preparing to farm. Little did he know his battle to get the property back would end up pitting him against a company controlled by the world’s richest school: Harvard University.

Over a decade, Harvard invested at least $1 billion in farmland, according to a just-released reportfrom the activist groups GRAIN, based in Barcelona, and the Network for Social Justice and Human Rights, based in Sao Paulo. The organizations came up with their estimate after a year-long investigation of tax returns and local property records, as well as on-the-ground interviews. Harvard’s holdings included vineyards in California, dairy farms in New Zealand, and operations producing cotton, soybeans, and sugar cane in countries such as Brazil, South Africa, Australia, Russia, and Ukraine, and totaled 854,000 hectares, though some assets have been sold.

In response to questions about its farmland holdings, Harvard says it considers the environmental and social implication of its endowment investments. The university said in a statement that it has “instituted a more proactive approach to working with managers of new and remaining assets—a partnership that provides more oversight and ensures that we can leave the land and community better than when we first invested.”

Narv Narvekar, the endowment’s chief executive officer hired from Columbia University in 2016 to overhaul operations, has retreated from direct investing. He’s spun out teams of managers overseeing assets from real estate to hedge funds, sending them to start their own businesses while investing with them. Yet Narvekar is still trying to hammer out the future of the troubled natural resources portfolio, even as he sells some investments, including the New Zealand dairy farm and a eucalyptus plantation in Uruguay.

Now, as a new school year begins, Harvard’s far-flung farmlands are facing criticism for, among other things, their impact on ancient burial grounds and impoverished populations. “Harvard’s farmland deals should be a cautionary tale for institutional investors,’’ writes Devlin Kuyek, a researcher at GRAIN, whose mission is to support small farmers and social movements in poorer countries.

Students, alumni, and environmentalists are targeting U.S. university endowments, saying their investing practices are often out of synch with schools’ professed values. These critics have pushed colleges to jettison stock in fossil fuel companies, private prisons, and companies that do business with Israel. Yale University’s investments in New Hampshire’s Great North Woods have drawn the school into disputes over clear-cutting and the development of a power line.

Harvard initially made hefty profits on its land investments, including by buying and selling New Zealand timberlands in the 2000s. But returns fell as emerging markets faltered, and much of the team spearheading the strategy left the endowment in 2015. Last year, Harvard wrote down its natural resources portfolio, which includes timber as well as farmland, by $1.1 billion, to $2.9 billion. Over the decade ended June 30, 2017, Harvard’s investment portfolio returned 4.4 percent a year, among the worst of its peers. In Brazil, in particular, the endowment’s holdings suffered from the country’s recent economic meltdown and political turmoil.

The report, titled “Harvard’s Billion-Dollar Farmland Fiasco,” shows why such investments are so risky. It highlights property Harvard bought in Australia through a company called Wealthcheck Funds Management. According to a government inquiry, the company harmed an Aboriginal burial site when it dug irrigation canals for a cotton farm. It also details conflicts between RussellStone Group, which managed the endowment’s farms in South Africa, and black families that were granted rights to some sites to graze cattle and access burial sites. Neither company returned calls or emails seeking comment.

But Brazil may be the most contentious of Harvard’s overseas adventures. A public prosecutor’s office in the northeastern state of Bahia, for instance, has said that it may sue to reclaim some of the 140,000-hectare farm owned by Harvard-backed Caracol Agropecuaria after finding that titles for about two-thirds of the property are invalid. In its most recent tax filing, Harvard valued its interest in Caracol at $87 million. Elsewhere in Bahia, villagers have protested the property titles of a farm that was in part sold to Harvard-backed Gordian Bioenergy, according to the report. The endowment has been seeking to end its relationship with Gordian, which is developing farms to produce both crops and energy, though it still controls assets it acquired through the company.

In the neighboring state of Piaui, a Harvard-controlled company called Sorotivo Agropecuaria has been battling with Grun and five other plaintiffs who say they lost their land in 2004. Earlier this year a judge dismissed the lawsuit and said Sorotivo could acquire a new title from the state for the 27,000-hectare farm it controls. However, in his decision he said that both the plaintiffs and Sorotivo practiced land-grabbing on title acquisitions. Accusations of land grabbing, which can date back decades, became epidemic as Brazil’s farm belt expanded and were often linked to speculators falsifying titles in order to steal and sell public property used by subsistence farmers.

The judge, Heliomar Rios Ferreira, says that the state agency from which the plaintiffs said they got their titles didn’t have any records of the grants. He also says Sorotivo improperly extended a boundary of its vast farm, though this was in an area unrelated to the lawsuit.

The plaintiffs’ lawyer says their property titles are legitimate and that they will appeal. Harvard controls Sorotivo through a Brazilian farming company called Insolo Agroindustrial, which didn’t return calls and emails seeking comment. A spokesman for Harvard declined to comment on the litigation.

While Grun relocated, people who for generations have made their home in the region known as the Cerrado are living with the consequences of the dispute. Eurotides Paulo da Silva resides in a village below Insolo’s vast farm, which stretches on for miles and miles and evokes a moonscape when it’s between harvest and seasonal plantings. His son works on the farm. But locals, who hunted and collected honey and medicinal plants on the plateaus, say their way of life has been hemmed in over the last decade with the arrival of industrial farms.

Silva produces a document dated from 1991 that he says shows his grandfather also owned land on the plateau. His cousin, Alberto Pereira da Silva, makes a similar claim, saying they never challenged the loss of the properties because they felt intimidated. Says the cousin: “We feel like we are trapped without a way out.” —With Lianne Milton

You may like

-

Six cattlemen opposed to the Tilenga oil project-related forced land eviction have been granted bail but will remain in prison…

-

Global agribusiness continues to displace rural communities

-

Court releases a tortured community land rights defender on bail

-

Breaking! Kiryandongo human rights situation is presented before the United Nations…

-

After being tortured by the army, the land rights defender is charged and remanded to prison

-

…….Special Report; abridged testimony……. ABDUCTION AND TORTURE: New methods used by multinationals and security agencies to grab land from the poor communities…

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Young activists fight to be heard as officials push forward on devastating project: ‘It is corporate greed’

Published

2 months agoon

August 27, 2025

“We refuse to inherit a damaged planet and devastated communities.”

Youth climate activists in Uganda protesting the East African Crude Oil Pipeline, or EACOP, are frustrated with the government’s response to their demonstration as the years-long project moves forward.

According to the country’s Daily Monitor, youth activists organized with End Fossil Occupy Uganda took to the streets of Kampala in early August to protest EACOP. The pipeline, under construction since about 2017 and now 62 percent complete, is set to transport crude oil from Uganda’s Tilenga and Kingfisher fields through Tanzania to the Indian Ocean port of Tanga by 2026.

Activists noted the devastating toll, with group spokesperson Felix Musinguzi saying that already around 13,000 people “have lost their land with unfair compensation” and estimating that around 90,000 more in Uganda and Tanzania could be affected. End Fossil Occupy Uganda has also warned of risks to vital water sources, including Lake Victoria, which it says 40 million people rely on.

The group has been calling on financial institutions to withdraw funding for the project. Following a demonstration at Stanbic Bank earlier in the month, 12 activists were arrested, according to the Daily Monitor.

Some protesters were seen holding signs reading “Every loan to big oil is a debt to our children” and “It’s not economic development; it is corporate greed.”

Meanwhile, the regional newspaper says the government has described the activist efforts as driven by foreign actors who mean to subvert economic progress.

EACOP’s site notes that its shareholders include French multinational TotalEnergies — owning 62 percent of the company’s shares — Uganda National Oil Company, Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation, and China National Offshore Oil Corporation.

The wave of young people taking action against EACOP could be seen as a sign of growing public frustration over infrastructural projects that promise economic gain while bringing harm to local communities and ecosystems. Activists say residents face costly threats from pipeline development, such as forced displacement and the loss of livelihoods.

Environmental hazards to Lake Victoria could also disrupt water supplies and food systems, bringing the potential for both financial and health impacts. Just 10 years ago, an oil spill in Kenya caused a humanitarian crisis. The Kenya Pipeline Company reportedly attributed the spill to pipeline corrosion, which led to contamination of the Thange River and severe illness.

The EACOP project has already locked the region into close to a decade of development, and concerns about the pipeline and continued investments in carbon-intensive systems go back just as long. Youth activists, as well as concerned citizens of all ages, say efforts to move toward climate resilience can’t wait. “As young people, we refuse to inherit a damaged planet and devastated communities,” Musinguzi said, per the Monitor.

Source: The Cool Down

Related posts:

Put people above profits – Climate Activists urge Total to defund EACOP

Put people above profits – Climate Activists urge Total to defund EACOP

EACOP: The number of activists arrested for opposing the project is already soaring in just a few months of 2025

EACOP: The number of activists arrested for opposing the project is already soaring in just a few months of 2025

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

The East African Court of Justice fixes the ruling date for a petition challenging the EACOP project.

The East African Court of Justice fixes the ruling date for a petition challenging the EACOP project.

WITNESS RADIO MILESTONES

Why matooke farming is losing ground in Bukedi

Published

2 months agoon

August 27, 2025

On a humid morning in Namusango Village, Kamonkoli South Ward, Kamonkoli Town Council in Budaka District, 58-year-old farmer James Kainja walks at the edge of what used to be his flourishing matooke garden. For generations, the green banana plant—matooke—stood tall in Uganda’s farmlands, its broad leaves swaying in the wind and its heavy bunches promising a warm, hearty meal. But in Bukedi Sub-region today, that story is fading. Between the tired banana stools, spear grass has taken over. A few bunches hang small and low quality. “We used to harvest every week,” Mr Kainja says, dusting his palms.

“Now, it is once in a while and the money is not worth the struggle,” he adds. Across Bukedi, particularly in Pallisa, Budaka, Butebo, and Kibuku, the banana plants are shrinking back, replaced by maize, cassava, rice, and other faster-growing crops. The sub-region that once sent truckloads of matooke to nearby districts now measures its banana harvest in small piles under tarpaulin. Where the green canopy of banana leaves once dominated, the landscape has changed. For many farmers, the decision is not about abandoning tradition but about survival.

Matooke as culture

In many Bukedi households, matooke still holds cultural value, especially during weddings, funerals, and community gatherings. But with fewer plantations, sourcing enough bunches has become harder and more expensive. Matooke is now imported into Bukedi from Mbale and Mbarara. Mr Abubakar Nanghejje, an elder in Kibuku, warns: “If this trend continues, our children may only know matooke from stories. We are losing more than a crop—we are losing a piece of who we are.”

He adds that matooke, once abundant, is now a luxury: “People only access matooke during ceremonies because the cost of a bunch has turned expensive,” he explains. Within Kibuku Town Council, women sell matooke in pieces: three or four fingers for Shs1,000, while a complete bunch costs between Shs30,000 and Shs35,000. This contrasts sharply with central and western Uganda, where matooke is more than a crop—it is an identity, a culture, and a livelihood. Yet across the country, banana plantations are thinning out, replaced by maize, beans, or simply abandoned.

Farmers’ voices

Mr Peter Mwigala, a 73-year-old farmer from Bubulanga Village, recalls with nostalgia: “I grew matooke for 30 years. But now my plantation is less than half what it used to be. The pests are too many, the prices are too low, and the rains are no longer reliable.” His story echoes across villages, evidence of a slow, steady decline in matooke production. This decline has unfolded over two to three decades, rather than as a sudden collapse. Agricultural researchers point to several reasons. Among them, banana bacterial wilt (BBW), banana weevils, and nematodes that have devastated plantations in major banana-growing areas. These pests cause premature ripening, rotting, and eventual uprooting of infected plants.

“When wilt enters your plantation, you can lose everything in one season,” says Mr Abner Botiri, an agriculture officer in Budaka. He further explains that erratic rainfall and prolonged dry spells also take a toll. Matooke thrives in consistent moisture, but under drought stress it yields smaller bunches. Repeated losses have led some farmers to abandon the crop entirely. Continuous cultivation without soil management has also depleted many banana-growing soils. Beyond agronomic challenges, the economics of matooke farming have shifted dramatically. Local market prices fluctuate widely depending on supply, while transport costs have risen sharply.

Mr John Gwanyi, a 71-year-old farmer, recalls: “In the 1980s and 1990s, matooke farmers could educate children through primary, secondary, and tertiary levels, and still cover basic needs. Today, a whole plantation might not pay for one term’s school fees.” Urbanisation has worsened the trend. Younger generations moving to towns now eat rice, spaghetti, and bread more frequently.

The once sacred matooke meal is no longer the undisputed centrepiece of Ugandan dining tables. Meanwhile, land fragmentation leaves families with smaller plots, unable to sustain large banana plantations. In some areas, higher-value or quicker-return crops like coffee, passion fruit, or maize dominate. As one agricultural economist notes: “A bunch of matooke takes nine months to mature, but maize can be ready in three months. For cash-strapped farmers, that difference matters.

Government interventions

Government and research institutions have made several attempts to address the situation. The National Agricultural Research Organisation (NARO) has introduced resistant banana varieties and promoted good agronomic practices. NGOs are training farmers in mulching, proper spacing, and integrated pest management. Still, the decline carries a cultural weight. In Buganda, for instance, matooke is central to marriage ceremonies, community gatherings, and daily life.

“When you serve matooke at a function, it shows respect,” explains Mr Badiru Kirya, a cultural leader in Obwa Ikumbania bwa Bugwere. Yet, Mr Kirya attributes part of the decline to newer banana varieties introduced by research agencies. “The old varieties planted by our grandparents could withstand weather changes better. These new varieties are weaker against climate volatility,” he says. He also notes that soil infertility and population pressure have accelerated the decline, as families squeeze more onto smaller pieces of land.

National standing

Uganda remains one of the world’s largest banana consumers, with per capita consumption estimated at 250–300 kg annually in some regions. Yet, national banana production has generally declined. According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) 2024 census, only 27.1 percent of households participate in banana cultivation. Dr Sadik Kassim, the NARO deputy director general in-charge of agricultural promotion, highlights several factors. “Soil fertility has gone low, while pests and disease build-up have grossly affected matooke gardens. Erratic rainfall and climate change further reduce yields.

Poor agricultural practices have made the decline worse,” he says. However, Dr Kassim dismisses the claim that new technologies are to blame. Similarly, Dr Rabooni Tumuhimbise, the director of research at Rwebitaba Zonal Agricultural Research and Development Institute, said: “As of now, I am not aware that Bukedi has registered a decline in banana production. This needs verification before conclusions.” But farmers and local leaders insist the reality is clear: matooke is disappearing from Bukedi. Mr Arthur Wako Mboizi, a seasoned politician and opinion leader, argues: “Bukedi has drastically registered a total decline in banana production due to various factors, including soil infertility, diseases, and erratic rainfall.”

Efforts are underway to add value. Under the Presidential Initiative on Banana, NARO and Kilimo Trust have developed matooke-based products such as flour, bread, and cakes. More than 13 million Ugandans consume bananas as their staple, and 75 percent of farmers grow them, contributing nearly $440 million annually to the economy. Yet, for Bukedi, the reality is sobering. The once proud producer of matooke is a shadow of its former self. As Mr Nanghejje, the Kibuku elder, put it: “We are losing more than a crop. We are losing a piece of who we are.”

Background

In 2024, national banana production was estimated at 6 million tonnes annually, 70 percent of which was consumed at household level and 30 percent sold.

The Banana Merchandise Trade Statistics Bulletin (2024) shows export earnings rose from $2.1 million in June 2023 to $2.4 million in June 2024. Still, yields remain below potential—currently 5–30 tonnes per hectare compared to an attainable 60–70 tonnes. Uganda’s banana losses to wilt disease are massive, with officials estimating a 71.4 percent loss of potential harvest annually, worth nearly $300 million.

Source: Monitor

Related posts:

Govt injects Shs47b into cassava growing in Bukedi

Govt injects Shs47b into cassava growing in Bukedi

Uganda’s natives are becoming more powerless; losing land everyday, says a New Research Report

Uganda’s natives are becoming more powerless; losing land everyday, says a New Research Report

Omoro farmers task Naro on crop varieties

Omoro farmers task Naro on crop varieties

Uganda losing agricultural advantage to neighbours – UN.

Uganda losing agricultural advantage to neighbours – UN.

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Cases against anti-EACOP activism are skyrocketing in Uganda. Witness Radio has documented close to 60 cases in the last eight months.

Published

3 months agoon

August 7, 2025

By the dedicated efforts of the Witness Radio team.

The Witness Radio team has documented nearly 60 cases of arrest, detention, and prosecution targeting activists protesting the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) since January 2025.

The $5 billion EACOP project, led by TotalEnergies and its partners, involves the construction of a 1,444km heated pipeline from Hoima in Uganda to Tanga in Tanzania. This pipeline, which will transport crude oil from the Tilenga and Kingfisher fields, has been a subject of controversy due to its potential environmental and social impacts.

As activism against the EACOP Project grows in Uganda, youth activists leading the cause face strong resistance from the government and its agents, who are pushing for the development of oil activities, including EACOP. Their bravery in the face of such adversity is truly inspiring.

The activists have continuously been suppressed and weakened with torture, unlawful arrests, and prolonged detentions accompanied by unscrupulous charges. The injustice they face is a call for empathy from all who hear their story.

The latest incident happened on Friday, August 1, 2025, when the police brutally arrested 12 environmental activists at Stanbic Bank Headquarters in Kampala. The urgency of the situation is apparent, as the activists were protesting against the bank’s financing of the EACOP project.

On March 26, 2025, EACOP Ltd., the company in charge of the construction and future operation of the EACOP project, announced new project financing from regional banks such as Stanbic Bank Uganda Limited, KCB Bank Uganda, African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), the Standard Bank of South Africa Limited, and the Islamic Corporation for the Development of the Private Sector (ICD). The announcement sparked widespread alarm and outcry, with activists urging the banks to immediately withdraw their support and halt the financing of the project.

These activists, individuals from Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) and environmental enthusiasts, strongly oppose the implementation of the EACOP project. They cite its harmful effects, including the displacement of thousands of people, damage to sensitive ecosystems, a threat to water resources, and exacerbating climate change mainly through carbon emissions. They argue that the short-term economic benefits do not justify these long-term consequences.

In doing their work, they have ended up in the hands of the authorities with numerous charges slapped against them. The latest remandees include Teopista Nakyambade, Shammy Nalwadda, Dorothy Asio, Shafik Kalyango, Habibu Nalungu, Noah Kafiiti, Ismael Zziwa, Ivan Wamboga, Akram Katende, Baker Tamale, Keisha Ali, and Mark Makobe.

On the same day of their arrest, the victims were arraigned before the Buganda Road Chief Magistrate Winnie Nankya, who charged them with common nuisance. She later remanded them to Luzira prison until August 18, 2025.

Section 160 of the Penal Code Act, Cap 120 states that a person convicted of common nuisance faces a one-year imprisonment.

In response, the Stanbic Bank manager for corporate communications, Mr. Kenneth Agutamba, confirmed that the bank is financing the EACOP project, justifying that it aligns with and balances environmental sustainability and economic development in the country.

Ever since this year started, Witness Radio has documented 56 cases of arrests and illegal detentions of EACOP activists, with most of them being charged with common nuisance. Below is a chronology of these incidents as they happened.

| Date | Incident | Charge |

| 26th Feb. 2025 | 11 activists were arrested while marching to the European Union offices deliver a petition concerning TotalEnergies’ involvement in harmful fossil fuels in Uganda. | Common nuisance |

| 19th Mar. 2025 | 4 activists were arrested while marching to the Parliament of Uganda to deliver a petition to the speaker, Anita Annet Among, in protest of the ongoing construction of the EACOP Project. | Common nuisance |

| 2nd April, 2025 | 9 activists were arrested while marching to Stanbic bank offices. | Common nuisance |

| 23rd of April, 2025 | A group of 11 activists were arrested as peacefully went to deliver a petition to KCB Uganda offices challenging its will to fund the EACOP project. | Criminal trespass. |

| 21 May 2025 | 9 activists arrested while protesting KCB financing of the EACOP | Common nuisance. |

| 1 Aug. 2025. | 12 activists arrested for protesting the Stanbic bank funding. | common nuisance |

According to Witness Radio’s special report, “Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP Protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems,” released last month, a case review revealed that while Uganda’s justice system is being used to suppress the activities of youth activists opposing the EACOP project, many of these cases have lacked merit and were ultimately dismissed.

The report found that none of the activists had been convicted, though they continue to face prolonged court processes marked by repeated adjournments. “Of a sample of 20 documented cases since 2022 involving the arrest of over 180 activists, 9 case files have either been dismissed by the courts or closed by the police due to lack of prosecution, another signal indicating the relevance and legitimacy of their work, while 11 cases remain ongoing,” the report noted.

Related posts:

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

Breaking: over 350,000 acres of land were grabbed during Witness Radio – Uganda’s seven months ban.

Breaking: over 350,000 acres of land were grabbed during Witness Radio – Uganda’s seven months ban.

EACOP: The number of activists arrested for opposing the project is already soaring in just a few months of 2025

EACOP: The number of activists arrested for opposing the project is already soaring in just a few months of 2025

Crackdown on EACOP protesters intensifies: 35 Activists arrested in just four months.

Crackdown on EACOP protesters intensifies: 35 Activists arrested in just four months.

Land Grabbing “matter of growing concern” in Uganda, Catholic Archbishop Laments, Appeals for Intervention

REC25 & EXPO Ends with a call on Uganda to balance conservation and livelihood

StopEACOP Coalition warns TotalEnergies and CNOOC investors of escalating ‘financial and reputational’ Risks

12 anti-Eacop activists decry delayed justice after spending 100 days on remand

The 4th African Forum on Business and Human Rights: The rapidly escalating investment in Africa is urgently eroding environmental conservation and disregarding the dignity, the land, and human rights of the African people.

Oil palm tree growing in Uganda: The National Oil Palm Project is threatening to evict hundreds of smallholder farmers to expand its operations.

StopEACOP Coalition warns TotalEnergies and CNOOC investors of escalating ‘financial and reputational’ Risks

The 4th African Forum on Business and Human Rights: The African continent is lagging, with only a few member states having adopted the National Action Plan (NAP) on Business and Human Rights.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

- PRESENDIANTIAL DIRECTIVE BANNING ALL LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoOil palm tree growing in Uganda: The National Oil Palm Project is threatening to evict hundreds of smallholder farmers to expand its operations.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoStopEACOP Coalition warns TotalEnergies and CNOOC investors of escalating ‘financial and reputational’ Risks

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoNew! The Eyes on a Just Energy Transition in Africa Program is now live on Witness Radio.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoKnow Your Land rights and environmental protection laws: a case of a refreshed radio program transferring legal knowledge to local and indigenous communities to protect their land and the environment at Witness Radio.

-

NGO WORK1 week ago

NGO WORK1 week agoFailed US-Brokered “Peace” Deal Was Never About Peace in DRC

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoRDCs, Local Leaders Accused of Grabbing 70-Acre Ancestral Land

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day agoREC25 & EXPO Ends with a call on Uganda to balance conservation and livelihood

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK6 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK6 days ago12 anti-Eacop activists decry delayed justice after spending 100 days on remand