FARM NEWS

How the Gates Foundation is driving the food system, in the wrong direction

Published

4 years agoon

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has spent nearly US$6 billion over the past 17 years trying to improve agriculture, mainly in Africa. This is a lot of money for an underfunded sector, and, as such, carries great weight.

To better understand how the Gates Foundation is shaping the global agriculture agenda, GRAIN analysed all the food and agriculture grants the foundation has made up until 2020.

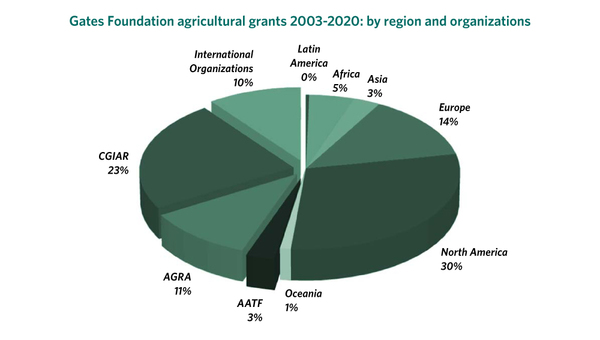

We found that, while the Foundation’s grants focus on African farmers, the vast majority of its funding goes to groups in North America and Europe.

The grants are also heavily skewed to technologies developed by research centres and corporations in the North for poor farmers in the South, completely ignoring the knowledge, technologies and biodiversity that these farmers already possess.

Also, despite the Foundation’s focus on techno-fixes, much of its grants are given to groups that lobby on behalf of industrial farming and undermine alternatives. This is bad for African farmers and bad for the planet. It is time to pull the plug on the Gates’ outsized influence over global agriculture.

In 2014 GRAIN published a detailed breakdown of the grants made by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to promote agricultural development in Africa and other parts of the world.1 Our main conclusion then was that the vast majority of those grants were channelled to groups in the US and Europe, not Africa nor other parts of the global South.

The funding overwhelmingly went to research institutes rather than farmers. They were also mainly directed at shaping policies to support industrial farming, not smallholders.

Much has happened since then. For starters, Bill and Melinda Gates announced their divorce in May this year, leaving the future of the Foundation and its grant-making in doubt. The news came as Bill Gates himself came under fire for supporting Big Pharma’s patent monopoly on COVID-19 vaccines, for effectively preventing people’s access across much of the world, and for how he treats – or mistreats – women.2 The Foundation’s agenda with agriculture has also been coming under increased scrutiny.

A 2020 report from Tufts University concluded that its work in Africa completely failed to meet the objectives that it had set itself.3 The African Centre for Biodiversity published a string of reports denouncing the Gates Foundation for pushing GMOs and other harmful technologies onto Africa.4

Amongst all this, the US Right to Know collective started a “Bill Gates Food Tracker” to monitor the multiple initiatives that Gates is involved in to reshape the global food system.5

GRAIN wondered whether the Gates Foundation had been receptive to the criticism of its food and agriculture funding. So we set out to update our 2014 report, downloaded the Foundation’s publicly available grant records and created a database of all of the Foundation’s grants in the area of food and agriculture from 2003 to 2020 – almost two decades worth of grant-making.6

The results are sobering. From 2003 to 2020 the Foundation dished out a total of 1130 grants for food and agriculture, worth nearly $US6 billion of which almost US$5 billion is supposed to service Africa.

There was no shift to try and reach groups in Africa directly, no refocusing away from the narrow technological approach, and no moves to embrace a more holistic and inclusive policy agenda.

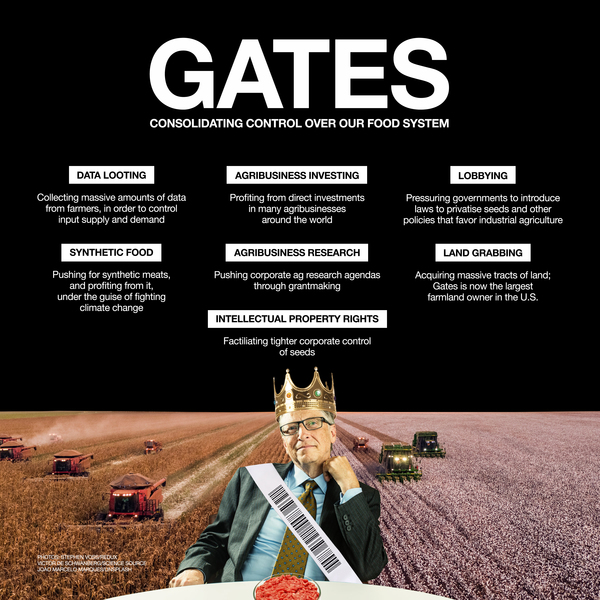

Of course, the Gates Foundation is about much more than just making grants. The Foundation’s Trust Fund, which manages the Foundation’s endowment, has big investments in food and agribusiness companies, buys up farmland, and has equity investments in many financial companies around the world.7

These, and other activities of Gates in the area of food and agriculture, are illustrated in the infographic that accompanies this report.8

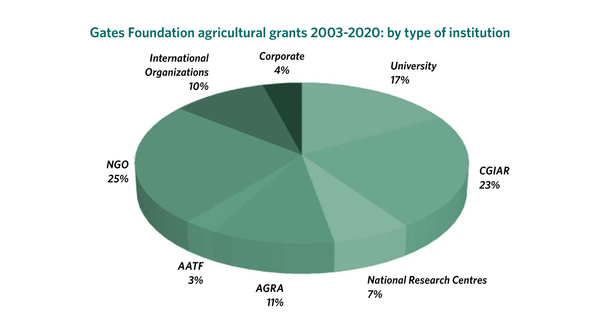

Graph 1 and Table 1 provide an overall picture of GRAIN’s research results. Almost half of the Foundation’s grants for agriculture went to four big groupings: the global agriculture research network of the Consortium Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA – set up in 2006 by the Gates Foundation itself together with the Rockefeller Foundation), the African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF – another technology centre pushing Green Revolution technology and GMOs into Africa) and a number of international organisations (World Bank, UN agencies, etc.).

The other half ended up with hundreds of research, development and policy organisations across the world. The Gates Foundation claims that 80% of their grants are meant to serve African farmers. But of the funding to these hundreds of organisations a staggering 82% was channelled to groups based in North America and Europe while less than 10% went to Africa-based groups.

The breakdown of the NGOs that the Gates Foundation funds is even worse. Almost 90% of this funding goes to groups in North American and Europe whilst just 5% is directly channelled to African NGOs. The Gates Foundation seems to have very little trust in African organisations serving African farmers.

Not that we would want the Gates Foundation to just send more of its grants directly to Africa if it comes with the same corporate industrial farming agenda. But it illustrates the point of where the priorities of the Foundation lie.

For contrast, Oxfam spends over half of all its funding directly in Africa, and over a third in Asia and Latin America, a lot of it through local NGOs in these regions.9

The Gates Foundation gives to scientists, not farmers

As can be seen in Graph 2, the single biggest recipient of grants from the Gates Foundation is the CGIAR- a consortium of 15 international research centres launched in the 1960s and 70s to promote the Green Revolution with new seeds, fertilisers and chemical inputs.

The Gates Foundation has given CGIAR centres US$1.4 billion since 2003. Another priority for the Gates Foundation in its funding is to support research at universities and national research centres. Again, the vast majority of the Gates’ grants go to universities and research centres in North America and Europe. Together, all this research gets almost half (47%) of the Gates Foundation’s funding.

The Gates Foundation’s support for Green Revolution-style research extends beyond the scientists. One of the most significant recipients of Gates Foundation funding is a high-profile advocacy organisation called the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). The Gates and Rockefeller Foundations launched AGRA in 2006 as a “farmer-centered” and “African-led” institution.

The reality is anything but. AGRA implements a top-down Green Revolution agenda with the main focus being to get new seeds and chemicals developed by Gates funded research centres and corporations into the hands of African farmers.

AGRA establishes, funds, coordinates and promotes networks of pesticide and seed companies and public agencies to sell and supply agriculture inputs to farmers across Africa. It also actively lobbies African governments to implement policies that favour seed and pesticide companies, such as patents on seeds or regulations that allow for GMOs.

The Gates Foundation has given AGRA a whopping US$638 million since 2006, covering almost two thirds of its overall budget. But AGRA’s results are underwhelming to say the least.

In the countries where AGRA is active, yields of staple crops increased only 18% over the past 12 years- far short of AGRA’s goal of doubling yields. Meanwhile, undernourishment (as measured by the FAO) increased by 30% in those countries.10

Instead of acknowledging that their data shows a complete failure to achieve their objectives and changing their approach accordingly, Bill and Melinda are doubling down. In early 2020 they launched their own new research institute called “Gates Ag One”.

This enterprise claims to speed up the development of new seeds and chemicals and get them to farmers in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia more quickly.11 Where will the institute be based? Not in Ethiopia or Sri Lanka but in St. Louis, USA, home of Monsanto and other GMO and pesticide giants.

The Gates Foundation buys political influence

In many subtle and not so subtle ways the Gates Foundation grants are used to push policy makers to implement its top-down industrial farming agenda.

One recent example is the 2021 “High-Level Dialogue on Feeding Africa” that was held on 29-30 April this year.12 This forum, funded by the Gates Foundation, and organised by a number of Gates Foundation grantees such as the African Development Bank, CGIAR and AGRA, was meant to launch a policy and funding agenda to further push the Green Revolution into Africa.

The event attracted no less than 18 African heads of state and several other high-profile personalities. But, most remarkable of all, is that of all the international organisations with activities in Africa on the long speakers list of the dialogue, virtually all are Gates grantees.

The forum concluded with a commitment to double agricultural productivity, something AGRA and the Gates Foundation have been promising and failing to deliver for the last decade and a half.

Of course, AGRA itself is also actively pushing the African policy agenda. AGRA is among the key conveners of the annual Africa Green Revolution Forum (AGRF) which calls itself the world’s premier forum for African agriculture and has been convening annual meetings for the past decade.

Partners include some of the main global agrochemical corporations, such as Bayer, Corteva and Yara, and of course the Gates Foundation itself. Unsurprisingly, its agenda is clearly oriented to push government policies towards more chemical inputs, fertilisers and hybrid seeds.

On its website, AGRF has a special section it calls the Agribusiness deal room, which “has directly facilitated over 400 companies with targeted investor matchmaking and hosted more than 800 companies to explore networking opportunities”.13 This is clearly market matchmaking serving corporate interests, not farmers.

While most of the Gates grants are aimed at pushing technological solutions, many are also oriented towards policy change. A total of 45 grants address policy or policy makers. For example, Iowa State University got a grant to support implementation of policy changes aimed at increasing the supply of new seeds to farmers in Africa.

The World Economic Forum received a grant to support a “policy platform for ag innovation and value chain development”, whilst the African Centre for Economic Transformation got a grant to promote agricultural transformation in Africa aimed at policy reforms. In addition, the Foundation is actively involved in bankrolling the “Enabling the Business of Agriculture” project, implemented by the World Bank, amongst many other initiatives.14

Gates’ enthusiasm for GMOs is made clear through its grant database. Michigan State University received US$13 million to create a centre in Africa that provides training for African policy makers on how to use and promote biotechnology. The African Seed Trade Association got a grant to increase farmers’ awareness “of the benefits of replacing their older varieties of crops with newer seed”.

AATF got US$32 million to increase awareness on the benefits of agricultural biotechnology and another US$27 million to fund the approval and commercialization GMO maize in at least four African countries.

So the Gates Foundation is not only funding public acceptance of GMOs, it is also directly funding the approval and commercialisation of GMOs in Africa.

Gates grantees are clearly carrying the Gates agenda and influencing global agricultural policy. In just over a decade, the Gates brainchild in Africa, AGRA, has managed to manoeuvre itself from nowhere right into the centre of agricultural policy discussions across the continent.

Similarly, while resistance to GMOs in Africa remains high, the AATF is managing to get legislation adopted to accept GMOs, as seen most recently in Ghana.

It’s just as important to look at who the Gates Foundation is supporting as who they are not supporting; African farmers.

The Foundation provides zero funding to support farmer seed systems, which supply 80 to 90% of all the seeds used in Africa. Instead, it provides a lot of funds to initiatives that destroy them.

Furthermore, the Gates Foundation props up biofortification as a solution to malnutrition, taking funds and attention away from much more practical and culturally appropriate efforts to improve nutrition by enhancing on-farm biodiversity and people’s access to it.15 Over the last decade or so, the Gates Foundation has given US$73 million to biofortification initiatives that essentially seek to artificially pack nutrients into single crop commodities.

Then, of course, there is Bill Gates himself. Sitting down with heads of state, policy makers and business leaders, Gates tries to convince them that his view of the world is the one to go after. The world has gotten used to pictures of him shaking hands or sitting shoulder to shoulder with the leaders of the world.

Indeed, many of those leaders seem very eager to be in these pictures and heed his advice. The most recent display of this was at Joe Biden’s virtual “Leaders Summit on Climate” where Gates shared his vision on how to fight the climate crisis.16

His recipe to tackle the climate crisis is very similar and equally dangerous to how he wants to feed the world: develop new technologies, trust the market, and put in place policies so that corporations can make it all happen faster.17

Gates clearly isn’t listening to or learning from the people on the ground. So why should anyone listen to him? Rather than being listened to, Gates and his top down corporate technology agenda must be resisted and stopped in its tracks.

GRAIN wishes to thank Camila Oda and María Teresa Montecinos for their help in compiling the database and to ‘A Growing Culture’ for their feedback on the draft and their work on the infographic.

Click here and here to consult all the food and agriculture grants of the Gates Foundation

Graph 1

|

Agency

|

$US million

|

Main recipients

|

|

CGIAR

|

1,373

|

The CGIAR is a consortium of 15 international research centres set up to promote the Green Revolution across the world. Gates is now amongst its major donors. Main recipients include: IFPRI ($223 million), CIMMYT ($346m), IRRI ($197m), ICRISAT ($151m), IITA ($166m), ILRI ($74m), CIP ($91m), and others. Most of the grants are in the form of project support to each of the centres, and many of them are focusing on developing new crop varieties.

|

|

AGRA

|

638

|

A total of 20 grants for core support and AGRA’s main issue areas: seeds, soils, markets, and lobbying African governments to change policies and legislation.

|

|

Int’l orgs (UN, World Bank, etc.)

|

601

|

World Bank – IBRD ($192m); World Food Programme (WFP) ($99m); UNDP ($54m.); FAO ($88m.) UN Foundation ($76m). The lion’s share of the grants to the World Bank are to promote public and private sector investment in agriculture ($70m), WFP is supported to improve market opportunities for small farmers, UNDP to establish rural agro-enterprises in West Africa, and the support to FAO is mostly for statistical and policy work.

|

|

AATF

|

170

|

AATF (African Agricultural Technology Foundation) is a blatantly pro-GMO pro-corporate research outfit based in Nairobi. The bulk of the Gates’ support is to develop GMO drought-resistant maize, a project that has already miserably failed according to many. But it also gets support to raise “awareness on agricultural biotechnology for improved understanding and appreciation”, and to get legislation approved for allowing GMOs in African countries.

|

|

Universities & National Research Centres

|

1,393

|

Over three quarters of all Gates’ funding to universities and research centres goes to institutions in the US and Europe, such as Cornell, Michigan and Harvard in the US, and Cambridge and Greenwich Universities in the UK, amongst many others. The work supported is a mix of basic agronomic, breeding and molecular research, as well as policy research. A lot of it includes genetic engineering. Michigan State University, for example, got $13m to help African policy-makers “to make informed decisions on how to use biotechnology”.

Although most of the Foundation’s grants are supposed to benefit Africa, barely 11% of its grants to universities and research centres go directly to African universities and research institutions ($147m in total, of which $30m for the Uganda based Regional University Forum set up by the Rockefeller Foundation).

|

|

Service delivery NGOs

|

1,446

|

The Gates Foundation sees these as agents to implement its work on the ground. They include both large development NGOs and foundations, and the activities supported tend to have a strong technology development angle or focus on policy and education work in line with the Foundation’s philosophy. A whopping 70% of these grants end up with US-based beneficiaries, and another 19% in Europe. African NGOs get 4% of the NGO grants ($73m total, $36m of which goes to groups in South Africa, and another $13m for “Farm Concern International”- an NGO based in Nairobi with the mission of building “market-led business models” for small farmers).

|

|

Corporations

|

244

|

A relatively minor share of Gates’ funding goes directly to the corporate sector. Most of the grants are for specific technologies developed by the corporations in question. Major grantees include the World Cocoa Foundation ($31m), a corporate outfit representing the world’s major food and cocoa processors, for improving marketing and production efficiency, and Zoetis (a Belgium based veterinary transnational – $14m) for getting veterinary products to farmers.

|

|

Total

|

5,865

|

|

Country

|

$US million

|

Main recipients

|

|

USA

|

1,657

|

The USA is by far the largest recipient country of Gates agricultural grants meant to benefit farmers in poor countries: $1,657 million dished out in over 400 grants. Recipients include US universities and research institutions to produce crop varieties and biotechnology research for farmers in Africa (e.g. Cornell University, a whopping $212m in 26 grants), big NGO projects mostly oriented to develop technology and markets (e.g. Heifer, $51m, to increase cow productivity and Technoserve Inc., $51m, to push new technologies), and several policy and capacity building projects to push the foundation’s agenda in Africa and elsewhere.

|

|

UK

|

466

|

A total of 81 grants with a focus on research such as for the University of Greenwich to work on pests and diseases in cassava and other crops (10 grants totalling $73m), and for the Global Alliance for Livestock Veterinary Medicines (9 grants totalling $169m) to produce livestock medicines and vaccines sold by the private sector to African farmers.

|

|

Germany

|

154

|

8 grants for the German Federal Enterprise for International Cooperation (GIZ) to develop supply chains for African cashew and rice farmers and other projects ($57m), and another three grants for the German Investment Corporation to work on African cotton and coffee farming ($47m), amongst others.

|

|

India

|

98

|

Total of 33 grants to a variety of grantees including three grants to PRADAN ($34m for women farmers training), and three grants to BAIF ($16m) to give farmers access to the latest livestock breeding technologies.

|

|

Netherlands

|

95

|

Mostly for five grants to the Wageningen University for agronomic research on grain legumes, supporting digital farming and other projects ($57m).

|

|

Canada

|

74

|

A total of 20 grants mostly towards universities to ensure adoption of new technologies, develop commercial cassava seed supply chains in Tanzania, and to produce vaccines for livestock diseases, amongst other programmes.

|

|

Australia

|

61

|

A total of 24 grants mostly to universities and research centres (including $30 million for the University of Queensland) to develop sorghum and cowpea hybrids for Africa, and provide genetically improved cattle, amongst other programmes.

|

|

China

|

48

|

Mostly for the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (two grants totalling $33 million) to develop new rice varieties for farmers across the world.

|

|

Uganda

|

46

|

Mostly for RUFORUM (two grants totalling over $30 million to support agricultural research universities in the region). RUFORUM was established as a programme of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1992 and became an independent Regional University Forum in 2004.

|

|

Kenya

|

43

|

Grants for Farm Concern International to create market-oriented value chains for a number of crops, and to a number of agribusiness companies active in the region to do the same.

|

|

Total top 10

|

2,742

|

$US2.7 billion, or almost half of all agriculture funding from Gates went to grantees in these 10 countries: over 90% to countries in the North.

|

Original Source: Grain.org

Related posts:

UN Food Systems Summit: The Battle Over Global Food and Agriculture Governance

UN Food Systems Summit: The Battle Over Global Food and Agriculture Governance

Bill Gates is the biggest private owner of farmland in the United States. Why?

Bill Gates is the biggest private owner of farmland in the United States. Why?

African Faith Communities Tell Gates Foundation, “Big Farming is No Solution for Africa

African Faith Communities Tell Gates Foundation, “Big Farming is No Solution for Africa

UN warns over looming food crisis in Uganda

UN warns over looming food crisis in Uganda

A smallholder tomato farmer in the northwestern Uganda region of West Nile sprays his half-acre tomato garden without adequate protection. Many farmers around the country interact with hazardous agro-chemicals without using adequate PPEs. COURTESY PHOTO/SASAKAWA AFRICA ASSOCIATION.

A consortium of civil society organisations (CSOs) has in a Jan.05 statement shown concern about the continued wrong use of dangerous pesticides in the country.

Members of the concerned CSOs mainly work to promote sustainable agricultural trade, food safety and sovereignty, climate justice, biodiversity restoration, and human and environmental rights.

The activists say there are growing concerns about pesticide misuse, including improper application and storage, counterfeit products, insufficient training in use, and use of poorly maintained or totally inadequate spraying equipment.

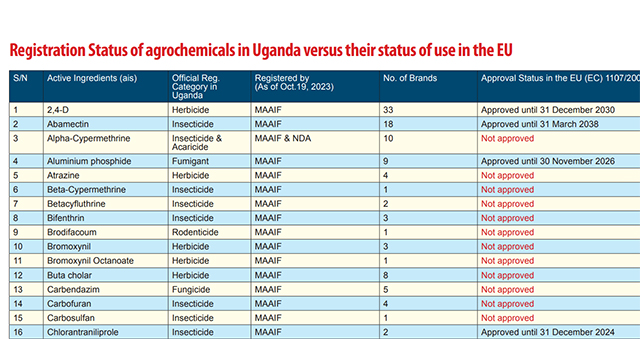

The activists insist the agriculture ministry should deregister at least 55 agro-chemicals that it registered in 2023 well-knowing that the same pesticides, herbicides and insecticides are banned by the European Union, a major market of Uganda’s agricultural produce.

Glyphosate-based herbicides, in particular, have raised significant alarm due to their potential environmental and health risks. Globally, they have been linked to contamination of water sources, soil degradation, and potential carcinogenic effects on humans.

In Uganda, glyphosate which appears in brands such as Rounduo and Weed Master, is widely used, especially among large-scale commercial farms and in weed control.

Betty Rose Aguti, the Policy and Advocacy Specialist at Caritas-Uganda who also doubles as the National Coordinator of Uganda Farmers Common Voice Platform says Uganda’s smallholder farmers need to be guided on the danger posed by some agro-chemicals.

“No one is guiding them on what to do with the agro-chemicals. Nobody is telling the farmers which agro-chemicals to use in what type of soils or on which type of crops and thereafter, what period of time they should take before they harvest.

“We have scenarios where some of these farmers apply these agro-chemicals bare-chested with no face masks and other protective gear; these farmers are using agro-chemicals as though they are using ordinary water.”

“They spray their gardens as they converse with their children and wives. In the course of doing this, they are inhaling the chemicals and after some time, they fall victim to the toxicity of these agro-chemicals and end up flooding the Uganda Cancer Institute,” she says.

What are pesticides?

Pesticides are defined by UN agencies; the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO), as substances or mixture of substances of chemicals or biological ingredients intended for repelling, destroying or controlling any pest, or regulating plant growth.

These often include ingredients that modify pest behaviour or their physiology (insect repellents) or affect crops during production or storage (herbicide safeners and synergists, germination inhibitors), as well as insecticides, fungicides and herbicides.

However, according to the activists, most of the chemicals on the Ugandan market are quite hazardous to both human health and the environment and yet they continue being used inappropriately by Ugandan smallholder farmers.

“We call upon the government of Uganda to regulate and ban all hazardous pesticides especially glyphosate and chlorpyriphos on the market in Uganda,” said Jane Nalunga, the Executive Director of the Uganda chapter of the Southern and Eastern Africa Trade Information and Negotiations Institute (SEATINI), a regional NGO that promotes pro-development trade, fiscal and investment-related poicies and processes.

Backbone of Uganda’s economy

The activists say Uganda’s agriculture sector is the mainstay of Uganda’s economy as it remains the main source of food, raw materials for industries, and employment of about 70% of Ugandans. The sector contributes about 24% to the country’s GDP.

“We cannot allow people with intellectual dishonesty to continue playing with the sector,” one of the activists said on Jan.5 during a press conference at the SEATINI-Uganda headquarters in Kampala. “We are aware that pesticides are significantly impacting health, biodiversity, socio-economic well-being, trade, and food security,” added Nalunga.

According to a 2020 World Health Organisation report, about 385 million cases of unintentional pesticide poisoning, including 11,000 deaths, mostly in low- and middle-income countries such as Uganda, are registered annually worldwide. According to UNICEF, pregnant and breastfeeding mothers, children under the age of five and the elderly are the most vulnerable to the effects of pesticides.

The activists say increased use of highly hazardous pesticides in Uganda is a threat to the right to adequate food, people’s livelihoods and farmers’ rights. They say pesticide runoff is reducing aquatic species diversity by 42% and threatening pollinators like bees. These insects are particularly critical for 75% of global crop production.

According to the European Environmental Agency, pesticides are intrinsically harmful to living organisms. When used outdoors, they can impact ecosystems even when they are intended to exclusively target a specific pest.

Herbert Kafeero, the Programme Manager at SEATINI-Uganda says the use of hazardous pesticides also has implications for trade. He says, in 2015, the government of Uganda imposed a self-ban on the export of agricultural produce to the EU because agro-chemical residues had been found in Uganda’s agricultural produce. “The self-ban was meant to address the challenges that were cited by the EU,” he says, “So we cannot ignore the fact that hazardous pesticides negatively impact the country’s trade and food security.”

He says, at the time, the government committed to retrain farmers and exporters to the EU regarding the EU’s sanitary and phytosanitary standards. Kafeero says the government must find solutions to the mushrooming agro-chemical dealers on the market.

“In every trading centre, you will not miss finding an agro-chemical shop and the person operating that agro-chemical shop presents himself as an expert when they actually are not.”

The activists want the Agricultural Chemicals Control Board under the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries to quickly profile the various agrochemicals, acaricides and inputs and their various sources that are available on the market in Uganda and ban the highly hazardous ones.

They also want the Department of Crop Inspection and Certification at the agriculture ministry to strengthen the regulation, management, use, handling, storage and trade of agrochemicals in the country.

They also want the government and other stakeholders to purposively plan and budget for education and awareness on the management, use, handling, storage and trade of agrochemicals in Uganda.

Prof. Ogenga Latigo disagrees

The activists were infact responding to Morris Ogenga Latigo, a Ugandan professor of entomology (study of insects) who had written an opinion on December 31, 2024, downplaying civil society’s concerns about hazardous pesticide and insecticide use in Uganda.

Prof. Ogenga Latigo in his article said the issue of agro-chemical use on farm pests and weeds and households was being exaggerated by civil society. He said the targeted agro-chemical inputs (pesticides, insecticides and herbicides) were being used in other countries.

The acrimonious debate has since sucked in the agricuture ministry. Stephen Byantware, the Director in charge of Crop Protection at the agriculture ministry told the media in Kampala recently that Uganda has an Agriculture Police Force and a Department of Inspection and Certification of agriculture inputs that “ensure that only nationally and globally approved agro-chemicals enter the Ugandan market.”

“The chemicals allowed into the country are those that have been approved,” he said, “There are no banned products on sale in Uganda. You cannot find DDT or Endosulfan in Uganda.”

But David Kabanda, the Executive Director of the Centre for Food and Adequate Living Rights, a Kampala-based non-profit, says Ugandans should know that hazardous pesticides have become one of the “loudest killers” and yet Ugandan smallholder farmers continue to associate with these chemicals on the farms, in the food stores, and in the homes.

“It’s only in Uganda where we don’t have a farmgate policy and yet we have scientific reports that have pointed out that the food we buy in markets in Kampala is contaminated.” “Don’t we see tomatoes and broccoli full of Mancozeb fungicide yet this chemical has been banned everywhere including the EU?”

“Pesticides are silent killers of humans, of nature, of our soils that are getting barren, of our water, of our agri-food system. I don’t imagine an agri-food system in Uganda without bees, without butterflies, and above all, without grasshoppers,” said Agnes Kirabo, the Executive Director of Food Rights Alliance (FRA).

Desperate smallholder farmers

According to the activists, Uganda’s agriculture system is by default largely organic but in recent years, pest and disease management has become one of the major production constraints for the country’s millions of subsistence farmers. And in recent years, farmers have turned to pesticides to control the pests.

According to the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations, the number of agricultural pesticides used in Uganda doubled in 12 years (2010 – 2022) from 2,990.23 tonnes to 6,009.78 tonnes.

Similarly, the monetary value of pesticides imported to Uganda more than doubled from US$ 32.57 million to US$75.87 million in 2022 with a peak import value of US$108.57 million reported in 2020. The lucrative agro-chemical business has attracted more than 40 registered pesticide importing companies in the country.

The activists say the increased use of pesticides is attributed to their use for weeding and the increased use of hybrid seeds and livestock. According to the CSOs, equally alarming is that many of these pesticides are “synthetic pesticides” which are persistent organic chemicals.

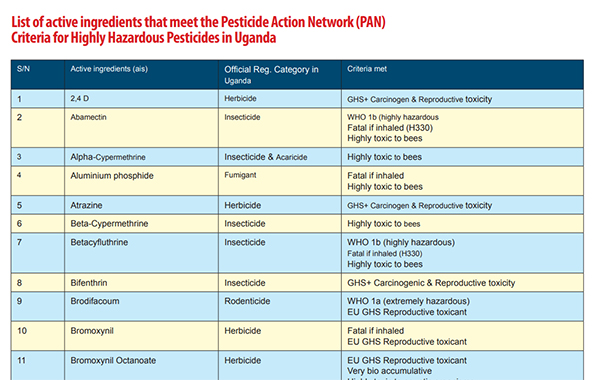

A study published last year by the Food Safety Coalition Uganda (FoSCU) titled: ‘‘Food Safety-Crop Protection Nexus: Insights from the Uganda’s agriculture sector,’’ noted that of the legally registered active ingredients, 47.8% (of the active ingredients) and 68.6% of the brands in Uganda qualified as “Highly Hazardous Pesticides.”

Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs) are classified as “reproductive toxicants” meaning they potentially can negatively affect the human reproductive system and have adverse effects on pregnancy outcomes and reduced fertility.

The same study noted that 15.6% of the registered active ingredients and 19.2% of the registered brands in Uganda qualified as highly hazardous pesticides in accordance with the FAO/WHO-Joint Meeting on Pesticide Management (JMPM) criteria.

According to the activists, by July 2023, over 65% of the 55 flagged active ingredients registered for use in Uganda and yet considered as highly hazardous pesticides according to the Pesticide Action Network (PAN) criteria, were not approved for use in the European Union economic bloc.

The majority (49%) of these pesticides are highly toxic to bees, 20% are carcinogenic and reproductive toxicants while 18% are probable carcinogens, and 9% are highly persistent in water and soil and are highly toxic to aquatic organisms.

They say that, based on the Uganda agrochemical register at the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF) and the National Drug Authority (NDA), the country had at least 115 active ingredients and 669 brands of synthetic pesticides legally registered for use in Uganda by the end of 2023.

“These are presenting in 459 brands, but all these active ingredients in the 459 brands, according to the PAN, are classified as highly hazardous,” said Bernard Bwambale, the head of programmes at the Global Consumer Centre, or CONSENT, who also coordinates the activities on food safety at the Food Safety Coalition of Uganda.

If it is hazardous in EU, it is hazardous in Uganda

Bwambale says his organisation has found that of the 55 active ingredients registered in Uganda, 65.5% of them cannot be used in their countries of origin. “Now, if a chemical, a highly hazardous chemical, is produced in a particular country and that country cannot use it, who are we to start thinking that we can use it? This is where our concern is.”

“So, whatever is not used in the EU, it means it’s not fit for use for human beings. The human beings in Uganda and the human beings in Europe are all human beings. And we are all sharing the same human rights.” He says some of the highly hazardous pesticides are mutagenic, meaning they can alter one’s DNA or genetic make-up.

“Literally, it would mean that when you consume food consisting of this kind of product, you stand a risk of your DNA or your genetic makeup being altered. And that is why some research is pointing to some of these chemicals being responsible for birth defects.” He says other chemicals are carcinogenic, meaning the chemical has the potential to cause cancer.

But Prof. Ogenga Latigo says some chemicals like Mancozeb the civil society claim are carcinogenic are not. He describes others as ‘probable carcinogens.’ A probable carcinogen is a substance that has a strong but not conclusive amount of evidence that it can cause cancer in humans.

But Bwambale says, “They don’t want people to keep confusing us with science.” He says other chemicals have been considered fatal when inhaled. “Imagine a farmer who doesn’t know these things and is spraying but is carrying a baby. So both the mother and the baby are inhaling this chemical,” he says, “We need to regulate these chemicals as much as we can.”

He says recent studies have indicated that some of these chemicals were found in human bodies –in sweat, urine and blood, in food and in water. “When the Europeans send us, for instance, these chemicals and we buy them, they also have regulations on which kind of food we can sell to them. We all know that.”

He says when farmers use these chemicals in the name of commercialising agriculture, they may produce very big tomatoes that do not rot, for example, but they cannot sell them beyond Uganda.

“You cannot put them on the EU market because they don’t meet the standard of the EU market. So they (agriculture products still remain with us,” he says.

Source: The independent

FARM NEWS

Coffee Leaf Rust disease hits Mbale region farmers

Published

8 months agoon

November 18, 2024

Mbale, Uganda | Coffee farmers from Bulambuli and Sironko districts are counting their losses after being attacked by coffee leaf rust disease. The disease, caused by the rust fungus Hemileia vastatrix, can reduce coffee production by between 30% to 50%.

The most affected sub-counties in Sironko include Buhugu, Masaba, Busulani, Bumasifwa, Bumalimba, and others. In Bulambuli, the hardest-hit areas are Lusha, Bulugeni Town Council, Buginyanya, and Kamu, among others.

In an exclusive interview with our reporter, Francis Nabugodi, the Sironko District Agricultural Officer, spoke about the devastating effects on farmers. “This disease has negatively impacted farmers in terms of production, and since it’s coffee season, they are going to make losses,” Nabugodi said.

He added that he had instructed extension workers to start massive sensitization campaigns in the six affected sub-counties about preventive measures, such as spraying, to curb the spread of the disease.

Nabugodi also urged the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Animal Husbandry to supply the district with chemicals so they can distribute them to farmers, as many cannot afford to buy them.

Julius Sagaiti, the LCIII Chairperson of Lusha Sub-County in Bulambuli District, stated that his sub-county is the worst affected, with over 100 farmers having all their gardens hit by the disease. He called for urgent action from Bulambuli district leaders, warning that the situation would have severe consequences for farmers.

Timothy Wegoye and Suzan Nanduga, both affected coffee farmers from Bukisa, the worst-affected sub-county, shared their concerns. “The majority of farmers are ignorant about preventive measures and do not know the chemicals for spraying,” they said, urging extension workers to use the media to sensitize them.

Original Source: URN Via The Independent

Along Bwera-Mpondwe road, in Kasese district, farmers till the land, with every hoe raising more dust than dirt, a testament of how hard the sun has scorched the ground. Located at the slopes of the Rwenzori Mountains, the low altitude leads to high temperatures as the district also sits on the Equator. In January this year, the average temperatures were 25.1 °C

Gideon Bwambale walks through drying maize garden.

Today, the temperature is 28.6 °C. The most affected areas are low-lying sub-counties like Kahokya, Nyakatonzi and Muhokya.

Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

A decade of displacement: How Uganda’s Oil refinery victims are dying before realizing justice as EACOP secures financial backing to further significant environmental harm.

Carbon Markets Are Not the Solution: The Failed Relaunch of Emission Trading and the Clean Development Mechanism

A decade of displacement: How Uganda’s Oil refinery victims are dying before realizing justice as EACOP secures financial backing to further significant environmental harm.

Govt launches Central Account for Busuulu to protect tenants from evictions

Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

Despite harsh repression, opposition to the EACOP pipeline in Uganda remains strong

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

- PRESENDIANTIAL DIRECTIVE BANNING ALL LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA

- FROM LAND GRABBERS TO CARBON COWBOYS A NEW SCRAMBLE FOR COMMUNITY LANDS TAKES OFF

- African Faith Leaders Demand Reparations From The Gates Foundation.

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS4 days ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS4 days agoActivism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

-

NGO WORK1 week ago

NGO WORK1 week agoCommunities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania