SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Colonization and Monoculture Plantations: Histories of Large-Scale ‘Grabbings’

Published

4 years agoon

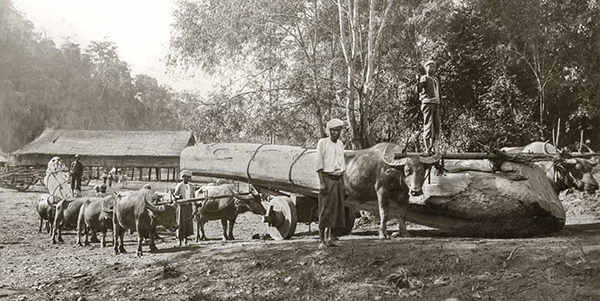

Forest colonization in Thailand.

The control of land was vital to colonisers. It meant wealth, territorial influence, access to ‘resources’ and cheap (and often enslaved) labour. The separation of indigenous inhabitants from their territories was a crucial component that persists until today. The effect of this history continues to influence the management of and conflicts over land.

Forest and agricultural policies the world over tend to regard land as just that: land. When it is perceived in this way, as simply a physical entity, ‘land’ can be easily mapped or divided up or rented out to others to use or regarded as a resource. This view of land emerged out of many decades of land enclosure and dispossession processes that were invariably carried out with force and accompanied by violence. The main purpose was to control land.

Most of the world’s land is today subject to some type of concession regime (be it private or public) in order to regulate its access, control and/or ownership. Concessions have been one of the main ways of organising land, forests and ‘resources’ since colonial times up until modern-day capitalism, granting select actors legal use or control over specific pieces of land while marginalising others. Together with the Bible, colonisers imposed a worldview in which ‘land’ was separate from the rest of ‘nature’, including its inhabitants.

As a result, most resistances against the history of imposed concessions, have also resisted the imposition of this euro-centric understanding of ‘land’, which is in line with the interests of the elites.

This view of ‘land’ has also distorted and undermined other concepts and understandings of life space. In the highlands of Sulawesi, Indonesia, for example, there is no word for ‘land’ in the peoples’ language. There is a word for ‘soil’ and several expressions for forests which express people’s relationship to it. There is no abstract category like ‘land.’ (1) And the concept of ‘land’ is not alone. During a meeting with an Indigenous Wixárika community in Jalisco, Mexico, in 2016, researcher and activist Silvia Ribeiro realised that people were using the Spanish language to refer to concepts such as ‘plant’ and ‘animal’. One community member explained to her: “We do not have a word for all animals that does not include us, or all plants without us, as if everything were one and we were not included.” Each animal, plant and living thing, just like every mountain, river, road—and even rock—has a name; because they are all subjects, part of the same continuum of beings that make up a territory’s community. (2)

Concessions by Dispossession: Controlling Land for Profits

The control of lands and ‘resources’ was vital to the colonisers; it was a strategy for accumulating more wealth, territorial influence, strategic access to ‘resources’ and cheap (and frequently enslaved) labour that allowed empires to flourish. They forcefully displaced, used and/or eradicated indigenous populations in order to have access to their lands. This separation of Indigenous Peoples from their territories and/or of their autonomy over their territories was a crucial component of colonisation, and one that persists in contemporary conservation strategies and forest carbon offset initiatives such as REDD+.

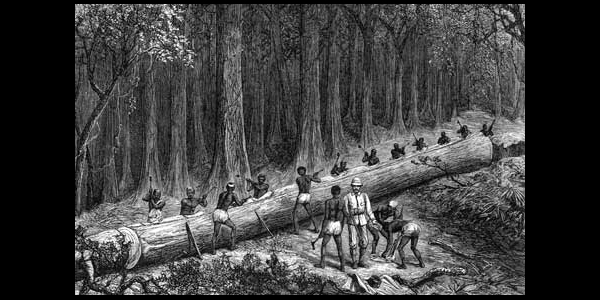

The ways in which colonisers imposed their control over land differed from one colony to another, or differed by the type of resource they were interested in, according to the geography of the colony. They also often changed throughout the colonial period. (3) In the wake of this colonial land grab, companies and wealthy settlers associated with the colonisers appropriated enormous tracts of land and established their business operations. (4)

In Southeast Asia, for example, large-scale plantation concessions were first established across the region by European colonisers for expanding and solidifying territorial control. This included the pacification of civil unrest in rural areas by imposing new estates of control, and the creation of new sources of capital accumulation, via rubber, coffee, tea, sugarcane and coconut plantations. The colonial governments of the region supported the development of rubber plantations by granting loans to private developers, such as Malaysia’s ‘Loan to Planters Scheme’ of 1904, and by granting lands at very cheap prices. In Peninsular Malaysia, areas considered ‘wastelands’ -although occupied and used by indigenous inhabitants– were provided to rubber investors. In French Indochina, where the rubber industry emerged in the 1920s, concessions were practically handed out to investors, which led to expansive land acquisitions that clashed with Indigenous Peoples (5).

The Agrarian Land Law that the Dutch colonial government promulgated in 1870 for what is now known as Indonesia, allowed foreign businesses and elites to occupy massive tracts of land. This Law contains the provision that “all land not held under proven ownership, shall be deemed the domain of the State”. Consequently, the Dutch colonisers claimed ownership of most of the land in their colony while weakening Indigenous Peoples’ control of their ancestral lands. This led to a surge of not only Dutch but also British, North American and Franco-Belgian investments, among others. Some companies had rubber holdings in the area totalling up to 100,000 hectares. This violently confined indigenous inhabitants into smaller and smaller areas of land. The effect of this history can still be seen today, as it continues to influence the character of land tenure in most parts of Indonesia: the State’s disproportionate control over land is still a blight on Indonesia’s politics and economy. (6)

British colonisers established a similar framework in Malaysia, focusing mainly on plantation-based economies that served long-term colonial interests. As researcher Amrita Malhi argues, “‘a regime of property’ replaced ‘customary modes of regulation’ and established the colonial State as the sole and centralised arbiter of land and its distribution”. (7)

However, British colonisers not only sought to consolidate their power through land control, but also to relocate the dispossessed population into more confined spaces. These new concessions of occupation -whether in terms of forest reserves established to study tree species and other productive ‘resources’, monoculture plantation estates or newly created villages for the displaced– divided Malaysia’s ‘nature’ and ‘social’ environments, allowing to generate more profits from the land. (8) In 1902, a Scottish capitalist, William Sime, and an English banker, Henry Darby, founded a trading firm in Malacca, with the participation of local Chinese businesspeople: Sime-Darby, the company which introduced the palm oil tree to Peninsular Malaysia in 1910 (9). Today, this corporation controls more than 620,000 hectares of oil palm plantations in Malaysia and Indonesia.

Another example is how the plantation system was utilised by British colonisation in the Americas as an instrument of land control and political power. The land on which plantations were established in North America and the Caribbean territories was stolen from Indigenous Peoples through cancelled, disregarded and fraudulent treaties, or outright violence. The monoculture plantation system of cash crops represented the early capitalist endeavours of the colonisers, who forcibly brought and sold millions of Africans as slaves to work on these plantations.

As these examples show, category of land concessions must be understood together with the rooted histories of colonisation, dispossession, conflicts and power.

These historical events led to dramatic transformations of forests and their inhabitants – transformations that are and will continue to have long-lasting devastating effects. The colonial framing that was imposed on how to perceive, understand and utilise ‘land’ continues to dominate Western knowledge systems. In a way, concessions, particularly those related to industrial plantations, today still represent spaces where land, livelihoods, law, and government are monopolised by, colonised by, and incorporated into the dominant colonial plantation system (10)

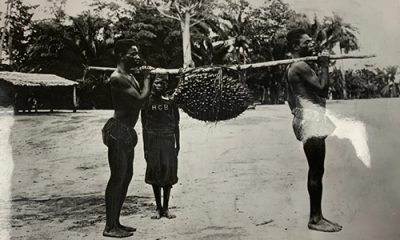

Concessions in Africa: violence, co-optation and racism

In Africa, European colonisers also granted vast land concessions to private companies. In fact, all major colonial powers on the continent used that strategy in order to expand their territorial control. By the mid-1870s, European colonisers had made claims to most parts of Africa. The most notorious case was arguably Belgian King Leopold II’s rule of the ‘Congo Free State’, which was his private colony for more than a decade (1895-1908).

Within Africa, concessions existed in French, British, Belgian, German, and Portuguese colonies (including what is known today as Angola, Botswana, Central African Republic, Cameroon, Chad, DRC, Gabon, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Republic of Congo, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe). While the form of concessions varied widely, a common element was the primary purpose of concession owners to extract ‘resources’ in the cheapest way possible. They were assigned powers that are typically associated with governments–such as a monopoly over violence and the ability to tax. Some colonies were completely run as concessions. For example, all of Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe) was granted as a concession to the British South Africa Company. Additionally, the concessions were often granted in ‘resource’ rich areas. (11)

Extreme labour exploitation, together with coercion and violence, was a primary condition for these companies to accomplish exorbitant profits with the concessions.

In sub-Saharan Africa, concessions to private companies were characterised by co-opting local institutions, replacing uncooperative leaders with compliant ones, and creating ruling lineages. With these tactics, concessions instituted a series of local strongmen who often continue to dominate village politics today. This is especially the case where concessions for monoculture plantations were established. Non-compliant leaders or rebellious chiefs were usually held captive, replaced, shamelessly degraded or murdered. Compliance with the rule of co-opted leaders was then achieved through extreme violence (12). As the European presence was mostly confined to the respective capitals and coastal cities, their ruling via co-opted chiefs and institutions characterised most of the continent.

While destroying local institutions, leadership and the social fabric, Europeans employed a variety of strategies to oppress the many resistance struggles and rebellions. These included forced-labour systems, extortion-level taxation on peasants, subjugation, and mass massacres. All of these conveyed deep consequences on today’s politics and organisations.

In Sierra Leone, for example, paramount chiefs, subordinate chiefs, and headmen ruled the country’s interior throughout the colonial era and were accountable solely to the colonial administration in the capital Freetown. The chiefs’ power endured and even strengthened after independence. Paramount chiefs became part of the state administration, which often brought them into conflict with their role as Chiefs in the traditional governing systems. Throughout the post-independence period, such chiefs controlled land, settled disputes, taxed production, provided some public goods, and allocated votes to their preferred candidates in national elections. (13)

Many newly independent nations in Africa, largely still embedded within the colonial frameworks, decided to nationalise their land, thus appropriating the rights to its use so that they could allocate vast tracts to be used for major agribusiness projects by public or private companies, and even individuals. Millions of hectares were thus legally confiscated (again) from local populations.

In this regard, social and environmental activist and human rights defender Nasako Besingi, explained in a 2018 interview with WRM that “it is wrong for any government to claim ownership over land, discarding communities’ land rights. As a matter of fact, the problem with Africa’s land ordinances is that they were drawn up with the help of colonial masters, who, without the consent of the population, handed over the territory to the presidents, who were not elected by the population but most often handpicked by the colonisers to serve their long-term interests.” (14)

The phrase ‘all land belongs to the State’, he continued, does not imply that land is owned by the government, but rather by the entire population living within the territory of a State. A government is best described as an agency to which the will of the State is formulated, expressed, and carried out, and through which common policies are determined and regulated in terms of political, economical and social development. Fulfilling those tasks does not translate into governmental ownership rights on land and natural resources of the State.

“Since I have been involved in community land rights’ movements and organisations in Cameroon and other countries”, said Besingi, “no single community I met accepted the idea that land is owned by the government. They say affirmatively that the land belongs to their communities and is an ancestral heritage. None of the communities I have worked with agrees with the presence of multinational corporations on their land, claiming that the companies were established through the use of coercive force.”

Categorising land and ‘resources’ as concessions is what has allowed the capitalist system to expand: Concessions for fossil fuel extraction, monoculture plantations, mining operations, large-scale corporate infrastructure, etc. Even the concessions under the ‘public realm’, such as those set aside for ‘conservation’, are entering the same capitalist logic of accumulation and taking control away from local populations.

The establishment of concessions, in fact, has been an attempt to erase the powerful resistance and survival of those who lived on those lands and forests before their imposition. When a concession is granted to a company or NGO, the histories, memories and the web of life that existed or continues to exist on that ‘land’ is made invisible. Concessions make people believe that the legitimate owners or users are not those who originally occupied, protected and worked on those territories. But as a Gitksan Elder remarked in a meeting with Canadian government officials over their claim to ownership of Gitksan territory: “If this is your land, where are your stories?” (15)

As Besingi remarked, a key aspect of communities’ resistance struggles in Africa is “to conquer the fear and ignorance deliberately instilled in the population by colonial and post-colonial administrations… Considering that long-lasting movements are those which are built from the base up and not from the outside, strong resistance can only occur when bonded with community concerns.”

Conflicts over land and resistance to the imposition of concessions today are thus embedded in much deeper historical struggles around opposite understandings of what ‘land’ and ‘nature’ mean. Communities’ reclaiming their autonomy and control over their land and lives are part of this re-occupation.

WRM International Secretariat

(1) Edge Effects, What is Land? A conversation with Tania Murray Li, Rafael Marquese, & Monica White, 2019.

(2) WRM Bulletin, December 2016, From Biodiversity Offsets to Ecosystem Engineering: New Threats to Communities and Territories.

(3) Nancy Lee Peluso & Christian Lund (2011) New frontiers of land control: Introduction, Journal of Peasant Studies, 38:4, 667-681.

(4) Roudart, Laurence and Marcel Mazoyer (2015) “Large-Scale Land Acquisitions: A Historical Perspective” in Large-Scale Land Acquisitions: Focus on South-East Asia, International Development Policy,

(5) Miles Kenney-Lazar and Noboru Ishikawa, Mega-Plantations in Southeast Asia: Landscapes of Displacement, 2019.

(6) Inside Indonesia, A 150-year old obstacle to land rights, 2020.

(7) Amrita Malhi (2011): Making spaces, making subjects: land, enclosure and Islam in colonial Malaya, Journal of Peasant Studies, 38:4, 727-746.

(8) David Baillargeon, Spaces of occupation: Colonial enclosure and confinement in British Malaya, 2021.

(9) Robert Fitzgerald, The Rise of the Global Company. Multinationals and the Making of the Modern World, 2016, Cambridge University Press

(10) Edge Effects, What is Land? A conversation with Tania Murray Li, Rafael Marquese, & Monica White, 2019.

(11) Sara Lowes and Eduardo Montero, Concessions, Violence, and Indirect Rule: Evidence from the Congo Free State, 2020.

(12) Idem (11)

(13) VoxDev, Historical legacies and African development, 2019.

(14) WRM Bulletin, December 2018, A Reflection from Africa: Conquer the Fear for Building Stronger Movements.

(15) J. Edward Chamberlin, If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?, Penguin Random House Canada.

Original Source: World Rainforest Movement

Related posts:

Conservation Concessions as Neo-Colonization: The African Parks Network

Conservation Concessions as Neo-Colonization: The African Parks Network

Large-scale irrigation facilities to be built in Atari Basin Area.

Large-scale irrigation facilities to be built in Atari Basin Area.

Monoculture tree plantations are a false climate solution

Monoculture tree plantations are a false climate solution

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

‘Food and fossil fuel production causing $5bn of environmental damage an hour’

Published

1 month agoon

December 22, 2025

UN GEO report says ending this harm key to global transformation required ‘before collapse becomes inevitable’.

Related posts:

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

New billion-dollar loans to fossil fuel companies from SEB, Nordea and Danske Bank.

New billion-dollar loans to fossil fuel companies from SEB, Nordea and Danske Bank.

Fossil fuel opponents lobby Africans for support

Fossil fuel opponents lobby Africans for support

Ecological land grab: food vs fuel vs forests

Ecological land grab: food vs fuel vs forests

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Britain, Netherlands withdraw $2.2 billion backing for Total-led Mozambique LNG

Published

2 months agoon

December 17, 2025

CONSTRUCTION HALTED IN 2021, BUT DUE TO RESTART

PROJECT CAN PROCEED WITHOUT UK, DUTCH FINANCING, TOTAL HAS SAID

CRITICISM FROM ENVIRONMENTAL, HUMAN RIGHTS GROUPS

Related posts:

Uganda, Total sign crude oil pipeline deal

Uganda, Total sign crude oil pipeline deal

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

NGOs file suit against Total over Uganda oil project

NGOs file suit against Total over Uganda oil project

Agribusiness Company with financial support from UK, US and Netherlands is dispossessing thousands.

Agribusiness Company with financial support from UK, US and Netherlands is dispossessing thousands.

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

The secretive cabal of US polluters that is rewriting the EU’s human rights and climate law

Published

2 months agoon

December 5, 2025

Leaked documents reveal how a secretive alliance of eleven large multinational enterprises has worked to tear down the EU’s flagship human rights and climate law, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). The mostly US-based coalition, which calls itself the Competitiveness Roundtable, has targeted all EU institutions, governments in Europe’s capitals, as well as the Trump administration and other non-EU governments to serve its own interests. With European lawmakers soon moving ahead to completely dilute the CSDDD at the expense of human rights and the climate, this research exposes the fragility of Europe’s democracy.

Key findings

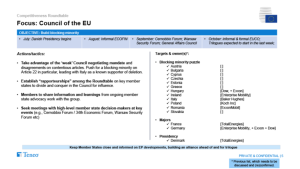

- Leaked documents reveal how a secretive alliance of eleven companies, including Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Koch, Inc., has worked under the guise of a “Competitiveness Roundtable” to get the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) either scrapped or massively diluted.

- The companies, most of which are headquartered in the US and operate in the fossil fuel sector, aimed to “divide and conquer in the Council”, sideline “stubborn” European Commission departments, and push the European People’s Party (EPP) in the European Parliament “to side with the right-wing parties as much as possible”.

- Chevron and ExxonMobil were in charge of mobilising pressure against the CSDDD from non-EU countries. The Roundtable companies endeavoured to get the CSDDD high on the agenda of the US-EU trade negotiations and also worked on mobilising other countries against the CSDDD, in order to disguise the US influence.

- Roundtable companies paid the TEHA Group – a think tank – to write a research report and organise an event on EU competitiveness, which echoed the Roundtable’s position and cast doubt on the European Commission’s assessment of the economic impact of the CSDDD.

While Europeans were told that their governments were negotiating a landmark law to hold corporations accountable for human rights abuses and climate damage, a secretive alliance of US fossil fuel giants was working behind the scenes to destroy it. Collaborating under the innocent-sounding name ‘Competitiveness Roundtable’, eleven multinational enterprises have worked closely to eviscerate several EU sustainability laws, including the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). This Competitiveness Roundtable may be unknown, but its members are a who’s-who of polluting, mainly US, multinationals, including Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Dow. The group seems to have run rings around all branches of the EU and the Trump administration to get what they want: scrapping, or at least hugely diluting, the CSDDD.

Leaked documents obtained by SOMO reveal how, under the pretext of the now-near-magical concept of ‘competitiveness’, these companies plotted to hijack democratically adopted EU laws and strip them of all meaningful provisions, including those on climate transition plans, civil liability, and the scope of supply chains. EU officials appear not to have known who they were up against. But the documents obtained by SOMO show a high level of organisation and strategising with a clear facilitator: Teneo, a US public relations and consultancy company.

The documents indicate that many of the companies involved wanted to stay hidden from view. After all, if it were widely known that a secretive group of mostly American fossil fuel companies like Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Koch, Inc. was working as a coordinated organisation to dilute an EU climate and human rights law, that might raise questions and serious concern among the public and the policymakers they were targeting. Many of the companies in the Roundtable have never publicly spoken out against the CSDDD.

Big Oil’s ‘Competitiveness Roundtable’

The Competitiveness Roundtable is dominated by fossil fuel companies, including three Big Oil companies (ExxonMobil, Chevron, TotalEnergies) and three other companies with activities in the oil and gas sector (Koch, Inc., Honeywell, and Baker Hughes). Other members are Nyrstar (minerals and metals, a subsidiary of Trafigura Group); Dow, Inc. (chemicals); Enterprise Mobility (car rentals); and JPMorgan Chase (finance).

Teneo, the Roundtable’s coordinator, has a track record(opens in new window) of working with fossil fuel companies, including Chevron, Shell, and Trafigura, and was hired by the government of Azerbaijan to handle public relations(opens in new window) when it hosted the COP29 climate conference.

In February 2025, the European Commission published the Omnibus I proposal(opens in new window), which aims to “simplify” several EU sustainability laws, including the CSDDD. The documents obtained by SOMO reveal that the Roundtable companies, which have been meeting weekly since at least March 2025, worked on deep interventions within each of the three EU institutions to get the Omnibus I package to align exactly with their views. The EU institutions are expected to reach a final agreement on Omnibus I by the end of 2025.

The documents reveal that the Roundtable companies’ activities in the Parliament are far more significant than what is visible in the EU Transparency Register(opens in new window). Eight of the Roundtable’s lobbying meetings during the Strasbourg plenary sessions of May and June 2025, listed in the Transparency Register, show Teneo as the only attendee, thereby failing to disclose the names of other Roundtable companies that participated in these meetings. Another three meetings the Roundtable held were not found in the EU Transparency Register(opens in new window) at all.

“Divide and conquer” the Council

In the European Council, the Roundtable plotted to “divide and conquer” EU governments to get the climate article in the CSDDD deleted. In June 2025, during the final weeks of negotiations in the Council on the Omnibus I proposal, the Roundtable discussed lobbying EU government leaders to “intervene politically” to ensure its priorities were included in the Council’s negotiation mandate. Subsequently, German Chancellor Merz and French President Macron reportedly(opens in new window) personally intervened(opens in new window) in the Council’s political process, leading to a dramatic dilution(opens in new window) of the texts(opens in new window) negotiated in the months before the intervention. Several of the changes made to the texts strongly align with the Roundtable’s demands, including delaying and substantially weakening the climate obligations, scrapping EU civil liability provisions, and limiting the responsibility of companies to take responsibility for their supply chains (the ‘Tier 1’ restriction).

Competitiveness Roundtable meeting document, 11 July 2025.

Additionally, the documents reveal that the Roundtable is still aiming to drum up a “blocking minority” to overturn the Council’s negotiation mandate during the trilogue negotiations, which started in November 2025. By “tak[ing] advantage of the ‘weak’ Council negotiating mandate” and disagreements between EU Member States on “contentious articles”, the Competitiveness Roundtable companies hope to force the Danish Council presidency to give up on including any form of climate obligations in the CSDDD – despite EU Member States’ agreement on this in the June 2025 Council mandate(opens in new window) .

To implement the divide-and-conquer strategy, the Roundtable assigned specific companies to “establish rapporteurships” with different EU governments. TotalEnergies would target the French, Belgian, and Danish governments, and ExxonMobil would target Germany, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Romania.

Circumventing “stubborn” European Commission departments

The Roundtable also discussed working on “circumvent[ing]” two “stubborn” European Commission departments involved in the Omnibus political process, DG JUST and DG FISMA, which, in their view, were “unlikely to be willing to see our side of the story”. According to the documents, DG JUST opposed deleting the climate article and restricting the Directive’s scope to only very large enterprises. The Roundtable aimed to diminish the role of these departments by pressuring President Von der Leyen and Commissioners McGrath (DG JUST) and Albuquerque (DG FISMA) by “organising letters from Irish and German business groups” and using an event held by the European Roundtable for Industry to “target” Von der Leyen and McGrath.

Read full report: Somo.nl

Source: Somo

Related posts:

Victims of human rights violations in Uganda still waiting for redress

Victims of human rights violations in Uganda still waiting for redress

UN Human Rights Chief urges EU leaders to approve key business and human rights legislation

UN Human Rights Chief urges EU leaders to approve key business and human rights legislation

Business, UN, Govt & Civil Society urge EU to protect sustainability due diligence framework

Business, UN, Govt & Civil Society urge EU to protect sustainability due diligence framework

Development financiers fuel human rights abuses – New Report

Development financiers fuel human rights abuses – New Report

Why govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

Evicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Swedish pension fund drops TotalEnergies amid rising EACOP risks

Land tenure security as an electoral issue: Museveni warns Kayunga land grabbers, reaffirms protection of sitting tenants.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoWomen environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoUganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

-

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoEvicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoWitness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days agoWhy govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry