SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Forest Colonialism in Thailand

Published

3 years agoon

British firms not only controlled 80 per cent of the established ‘logging lands’ in Thailand, but they also influenced the establishment of the Royal Forest Department, which came to have total power over the nation’s forests. Massive land grabs and various colonial laws made half the country’s territory into a colony of the central state.

A 19th-Century Concession System

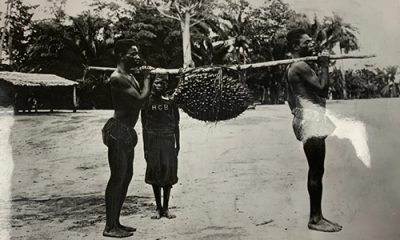

In 1874, during the age of European colonialism, the Siamese monarchy based in Bangkok annexed Chiang Mai in what is now Northern Thailand as its own colony. Under the Chiang Mai Treaty, a Siamese forest concession model was imposed in 1883 that allowed European companies direct access to the region’s large teak tracts, with much of the profit to be divided with the monarchy in Bangkok.

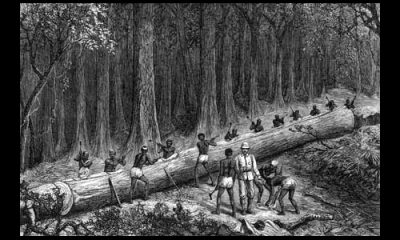

Between 1889 and 1896, UK’s Bombay Burmah Company, British Borneo Company, Siam Forest Company Ltd. and Louis T. Leonowens Ltd., and Denmark’s East Asiatic Co., commenced logging in earnest. (1) British firms controlled 80 per cent of the established so-called ‘logging lands’. (2) They also played a role in the establishment of the Royal Forest Department in 1896, which came to have total power over the nation’s forestry activities. A British national was head of the Department for the following 28 years, and British logging activities extended over seven decades.

Forest Colonies

Under the country’s first forest law of 1913, the Forest Preservation Act, forests were defined very much in terms of colonial occupation. Any land without royally-granted title deeds permitting cultivation or house construction was considered under the control of the Forest Department. Accordingly, the Department was able to amass large areas of land for logging concessions on which farmers without land documentation were already living, relying for part of their subsistence on forests.

The 1938 Forest Protection and Preservation Act maintained the same spirit, defining forests as ‘waste’ or unoccupied land in the public domain. Similarly, the 1941 Forest Act regarded forests as land that had “not yet been acquired by anyone under the Land Law”. These laws effectively made half the country’s territory into a forest colony of the central state, annexing community lands, forests, fields and village territories alike.

125 Years of Forestry

Thai forestry activities and forestry science grow out of the history of teak logging in the country’s North from 1840 onward. In Northern centres of the government such as Chiang Mai, Lampoon and Lampang, nobles had originally granted permission to various Chinese, Burmese and Thai Yai (ethnic nationality across Southeast Asia) businesses to extract teak for a fee. Then, in 1855, the central Siamese state signed the trade agreement known as the Bowring Treaty with Britain. This enabled the British, as well as ethnic nationalities under British rule including the Burmese, Thai Yai and Mon, to expand teak logging in the region. Thus the British Borneo Company was already on the scene in 1864 as a timber purchaser, even before the formal annexation of Chiang Mai as a Siamese colony ten years later.

It was only in 1954-55 that the vast logging concessions granted to foreigners expired and were turned over to Thailand’s Forest Industry Organization and provincial logging firms. By that time, the country’s mature native teak stands were largely exhausted, and concessionaires were turning to other commercial species. The following decades saw the country’s deforestation rates rise to become among the highest in the world, driven largely by the expansion of commercial agriculture but also by logging under the concession system as well as dam construction, both of which often opened up new areas for cultivation. Logging had a wide impact on forests that had been preserved and maintained by local communities for their own use, spurring resistance in the North and elsewhere in the country and motivating a growing Thai environmental movement. Logging was finally banned in 1989.

Authoritarian Conservation

As the logging era waned in the 1980s, the focus of the forestry establishment shifted toward commercial industrial tree plantations and forest conservation. But the pattern of internal colonialism remained, accompanied by growing local resistance to state hegemony over lands, including forests, used by millions of villagers.

Although the Thai government enacted two conservation laws in the early 1960s, the Wildlife Preservation and Protection Act and the National Park Act, it was only after logging was banned, 93 years after the Forest Department was established, that official conservation thinking really took off. Conservation areas expanded bit by bit, encroaching especially on minority communities residing in highland areas, first taking over former logging concessions, then expanding further in line with the recommendation of UN-FAO’s ‘experts’ that Thailand should have no less than 40 per cent tree cover. As a result, ordinary villagers have been deprived of access to needed resources, government units have been set up close to communities to limit their use of forests, and many people have been evicted from their land. Violent conflicts between rural villagers and the state have increased.

The latest amendments to Thai forest law – following the military coup of 2014 that resulted in retired army general Prayut Chan-O-Cha becoming Prime Minister – include the fourth National Reserved Forests Act of 2016, the National Parks Act of 2019, and the Wildlife Preservation and Protection Act of 2019. Violations carry increased penalties of one to 20 years (3) in prison and fines of between US 600 and 60,000 dollars. Recent years have also seen legal cases brought against villagers for damage to ‘natural resources’ and for contributing to global warming. Residents on state forest land have been unjustly sued for damages with huge fines that they have no means of paying.

The new laws have greatly increased the power of officials to make arrests and seize property in National Park areas. To be able to stay on their land without threats of prison or fines, community members must obtain residence permits with a time limit of 20 years (4) as well as special permission to use the forests. Indeed, in many ways, National Reserve Forests and National Parks now resemble territories under martial law. There are strong echoes of the 1914 Martial Law Act promulgated during the First World War, which gave military officials power overriding that of civilian authorities, allowing them to search persons, vehicles or buildings at will; issue prohibitions; seize goods; build strongholds; expel the populace; and destroy or modify terrain or burn down houses to deny the enemy any advantage in battle.

Since the complex colonization processes of forested lands in the country, racist and oppressive views over forests and its inhabitants were imposed. This colonial mind-set has continued to influence national decision and policy-making, seriously harming forest communities, who are largely falsely considered as intruders or damaging the forests. This in turn is manifested with extreme violence and discrimination towards these communities and their traditional livelihoods and cultural practices.

Despite the difficult and forceful circumstances, forest communities continue to challenge and struggle against this oppressive context. In early 2021, indigenous Karen People from Bang Kloi returned to their ancestral home in the Kaeng Krachan forests, after years of dispossession due to the creation of the Kaeng Krachan National Park. Thirty people were arrested for “encroaching the national park”. (5) They are forbidden from returning or trespassing on the Park without permission. If they still disobey, they will be withdrawn on bail and sent to prison immediately.

It is clear that the Karen People fighting to have their territory back is not only about the land, but it is also about recovering their identity, culture, dignity and lives from a history of colonization and occupation.

Pornpana Kuaycharoen

Land Watch Thai

(1) Master Thesis, “Development of teak logging in Thailand 1896-1960”, Salarirat Dolarom, Silpakorn University, Thailand, 1985

(2) Idem (1)

(3) Section 30 under the National Reserved Forests Act B.E. 2019 and Section 41 under the National Parks Act B.E. 2019. See National Parks Act 2019, English version here.

(4) Section 64 under the National Reserved Forests Act B.E. 2019

(5) Thailand’s imposition of National Parks: The Indigenous Karen People’s struggle for their forests and survival, WRM Bulletin 254, March 2021; and ALERT! Karen indigenous communities face danger after returning to their ancestral territory in Thailand.

Original Source: World Rainforest Movement

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

‘Left to suffer’: Kenyan villagers take on Bamburi Cement over assaults, dog attacks

Published

3 months agoon

March 22, 2025

- The victims are aged between 24 and 60, and one of them has since passed on.

- Many were severely injured and hospitalized following brutal attacks, unlawful detention, and physical assault by Bamburi’s security personnel.

Editor’s note: Read the petition here.

Their hopes for justice seemed to be slipping away after initially taking on a multinational corporation and failing to hold it accountable for the brutal injuries they suffered.

The death of one of their own cast a shadow of despair, making it seem unlikely that they would ever bring the corporation to justice for the crimes they alleged.

However, 11 victims of dog attacks, assaults, and other severe human rights violations are now challenging Bamburi Cement PLC’s role in these abuses in court.

They are represented by the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC), which on January 29, 2025, filed a legal claim before a constitutional court in Kenya, seeking to hold the multinational accountable for the harm suffered by the victims—residents of land parcels in Kwale that Bamburi claims ownership of. KHRC worked with the Kwale Mining Alliance (KMA) to bring this case.

The victims, aged between 24 and 60, include Mohamed Salim Mwakongoa, Ali Said, Abdalla Suleiman, Hamadi Jumadari, Abdalla Mohammed, and Omari Mbwana Bahakanda. Others are Shee Said Mbimbi, Omar Mohamed, Omar Ali Kalendi (deceased), Abdalla Jumadari, and Bakari Nuri Kassim.

Bamburi had hired a private security firm and deployed General Service Unit (GSU) officers to guard three adjoining land parcels, covering approximately 1,400 acres in Denyenye, Kwale. The GSU established a camp on the land, which has historically been accessed by residents who have long used established routes to reach the forest and the Indian Ocean.

For decades, these routes provided them with access to resources such as firewood, crops, and fish, which they relied on for their livelihoods. However, five years ago, when they attempted to collect firewood, harvest crops, and access the ocean through the land, Bamburi accused them of trespassing. The company’s private guards and GSU officers responded with force, setting dogs on them and assaulting them.

Many were severely injured and hospitalized following brutal attacks, unlawful detention, and physical assault by Bamburi’s security personnel. These incidents occurred despite the lack of clearly defined boundaries and the fact that the traditional access routes had never been contested.

According to the petition, GSU officers and private guards inflicted serious injuries by kicking, punching, and beating the victims with batons. Those who were arrested were neither taken to a police station nor charged with any offense. Despite their injuries, they were denied emergency medical care.

These actions were intended to intimidate residents, prevent them from accessing the beach, and suppress any historical claims to the land, the victims tell the court. Local police in Kwale failed to investigate the abuses, visit the crime scenes, or arrest any of the perpetrators, they add.

Now, the victims are seeking compensation for these violations. They have also asked the court to declare that their rights were violated through torture inflicted by Bamburi’s guards and GSU officers. Additionally, they want the court to rule that releasing guard dogs to attack them during arrests constituted an extreme and unlawful use of force.

Source: khrc.or.ke

Related posts:

Breaking: Over 600 attacks against defenders have been recorded in the year 2023 globally- BHRRC report.

Breaking: Over 600 attacks against defenders have been recorded in the year 2023 globally- BHRRC report.

Kaweeri Coffee land grabbing case re-trial resumes as evictees continue to suffer gross human rights violations.

Kaweeri Coffee land grabbing case re-trial resumes as evictees continue to suffer gross human rights violations.

Criminalization of planet, land, and environmental defenders in Uganda is on the increase as 2023 recorded the soaring number of attacks.

Criminalization of planet, land, and environmental defenders in Uganda is on the increase as 2023 recorded the soaring number of attacks.

Local land grabbers evict villagers at night; foreign investors cultivate the same lands the next day

Local land grabbers evict villagers at night; foreign investors cultivate the same lands the next day

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

River ‘dies’ after massive acidic waste spill at Chinese-owned copper mine

Published

3 months agoon

March 22, 2025A catastrophic acid spill from a Chinese-owned copper mine in Zambia has contaminated a major river, sparking fears of long-term environmental damage and potential harm to millions of people.

The spill, which occurred on February 18, has sent shockwaves through the southern African nation.

Investigators from the Engineering Institution of Zambia revealed that the incident stemmed from the collapse of a tailings dam at the mine.

This dam, designed to contain acidic waste, released an estimated 50 million litres of toxic material into a stream feeding the Kafue River, Zambia’s most important waterway.

The waste is a dangerous cocktail of concentrated acid, dissolved solids, and heavy metals.

The Kafue River, stretching over 930 miles (1,500 kilometres) through the heart of Zambia, supports a vast ecosystem and provides water for millions. The contamination has already been detected at least 60 miles downstream from the spill site, raising serious concerns about the long-term impact on both human populations and wildlife.

Environmental activist Chilekwa Mumba, working in Zambia’s Copperbelt Province, described the incident as “an environmental disaster really of catastrophic consequences”.

The spill underscores the risks associated with mining, particularly in a region where China holds significant influence over the copper industry.

Zambia ranks among the world’s top 10 copper producers, a metal crucial for manufacturing smartphones and other technologies.

Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema has appealed for expert assistance to address the crisis. The full extent of the environmental damage is still being assessed.

A river died overnight

An Associated Press reporter visited parts of the Kafue River, where dead fish could be seen washing up on the banks about 60 miles downstream from the mine run by Sino-Metals Leach Zambia, which is majority owned by the state-run China Nonferrous Metals Industry Group.

The Ministry of Water Development and Sanitation said the “devastating consequences” also included the destruction of crops along the river’s banks. Authorities are concerned that ground water will be contaminated as the mining waste seeps into the earth or is carried to other areas.

“Prior to February 18 this was a vibrant and alive river,” said Sean Cornelius, who lives near the Kafue and said fish died and birdlife near him disappeared almost immediately.

“Now everything is dead, it’s like a totally dead river. Unbelievable. Overnight, this river died.”

About 60 per cent of Zambia’s 20 million people live in the Kafue River basin and depend on it in some way as a source of fishing, irrigation for agriculture and water for industry. The river supplies drinking water to about five million people, including in the capital, Lusaka.

The acid leak at the mine caused a complete shutdown of the water supply to the nearby city of Kitwe, home to an estimated 700,000 people.

Attempts to roll back the damage

The Zambian government has deployed the air force to drop hundreds of tons of lime into the river in an attempt to counteract the acid and roll back the damage. Speed boats have also been used to ride up and down the river, applying lime.

Government spokesperson Cornelius Mweetwa said the situation was very serious and Sino-Metals Leach Zambia would bear the costs of the cleanup operation.

Zhang Peiwen, the chairman of Sino-Metals Leach Zambia, met with government ministers this week and apologized for the acid spill, according to a transcript of his speech at the meeting released by his company.

“This disaster has rung a big alarm for Sino-Metals Leach and the mining industry,” he said.

It “will go all out to restore the affected environment as quickly as possible”, he said.

Discontent with Chinese presence

The environmental impact of China’s large mining interests in mineral-rich parts of Africa, which include Zambia’s neighbors Congo and Zimbabwe, has often been criticised, even as the minerals are crucial to the countries’ economies.

Chinese-owned copper mines have been accused of ignoring safety, labour and other regulations in Zambia as they strive to control its supply of the critical mineral, leading to some discontent with their presence.

Zambia is also burdened with more than $4 billion in debt to China and had to restructure some of its loans from China and other nations after defaulting on repayments in 2020.

A smaller acid waste leak from another Chinese-owned mine in Zambia’s copper belt was discovered days after the Sino-Metals accident, and authorities have accused the smaller mine of attempting to hide it.

Local police said a mine worker died at that second mine after falling into acid and alleged that the mine continued to operate after being instructed to stop its operations by authorities. Two Chinese mine managers have been arrested, police said.

Both mines have now halted their operations after orders from Zambian authorities, while many Zambians are angry.

“It really just brings out the negligence that some investors actually have when it comes to environmental protection,” said Mweene Himwinga, an environmental engineer who attended the meeting involving Mr Zhang, government ministers, and others.

“They don’t seem to have any concern at all, any regard at all. And I think it’s really worrying because at the end of the day, we as Zambian people, (it’s) the only land we have.”

Source: www.independent.co.uk

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

How Carbon Markets are Exploiting Marginalised Communities in the Global South Instead of Uplifting them

Published

7 months agoon

December 11, 2024

The billion-dollar fiction of carbon offsets

Carbon markets are turning indigenous farming practices into corporate profit, leaving communities empty-handed.

For Janni Mithula, 42, a resident of the Thotavalasa village in Andhra Pradesh, cultivating the rich, red soil of the valley was her livelihood. On her small patch of land grow with coffee and mango trees, planted over decades with tireless care and ancestral knowledge. Yet, once a source of pride and sustainability, the meaning of these trees has been quietly redefined in ways she never agreed to.

Over a decade ago, more than 333 villages in the valley began receiving free saplings from the Naandi Foundation as part of a large-scale afforestation initiative funded by a French entity, Livelihoods Funds. Unbeknownst to Janni and her neighbours, these trees had transfigured into commodities in a global carbon market, their branches reaching far beyond the valley to corporate boardrooms, their roots tethered not to the soil of sustenance but to the ledger of profit and carbon offsets.

The project claims that it would offset nearly 1.6 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent over two decades. On paper, it is a triumph for global climate efforts. In reality, the residents’ lives have seen little improvement. While the sale of carbon credits has reportedly fetched millions of dollars for developers, Janni’s rewards have been minimal: a few saplings, occasional training sessions, and the obligation to care for trees that she no longer fully owns. These invisible transactions pose a grave risk to marginalised communities, who practice sustainable agriculture out of necessity rather than trend.

Also Read | COP29: The $300 billion climate finance deal is an optical illusion

The very systems that could uplift them—carbon markets intended to fund sustainability—end up exploiting their resources without addressing their needs.

Earlier this year, the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) and Down To Earth (DTE) released a joint investigative report on the functioning of the voluntary carbon market in India. The report critically analysed the impacts of the new-age climate solution, its efficacy in reducing carbon emissions, and how it affected the communities involved in the schemes.

The findings highlighted systemic opacity, with key details about the projects, prices, and beneficiaries concealed under confidentiality clauses. Developers also tended to overestimate their emission reductions while failing to provide local communities with meaningful compensation. The report stated that the main beneficiaries of these projects were the project developers, auditors and companies that make a profit out of the carbon trading system.

Carbon markets: The evolution

On December 11, 1997, the parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) convened and adopted the Kyoto Protocol with the exigence of the climate crisis bearing down on the world. The Kyoto Protocol, revered for its epochal impact on global climate policy, focused on controlling the emissions of prime anthropogenic greenhouse gases (GHGs). One of the key mechanisms introduced was the “Clean Development Mechanism”, which would allow developed countries to invest in emission reduction projects in developing countries. In exchange, the developed countries would receive certified emission reduction (CER) credits, or carbon credits as they are commonly known.

One carbon credit represents the reduction or removal of one tonne of CO2. Governments create and enforce rules for carbon markets by setting emission caps and monitoring compliance with the help of third-party organisations. For example, the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS) sets an overall cap on emissions and allocates allowances to industries. A financial penalty system was also put in place to prevent verifiers and consultants from falsifying emissions data. The impact of these renewable projects is usually verified through methods such as satellite imagery or on-site audits.

Companies such as Verra and Gold Standard have seized this opportunity, leading the designing and monitoring of carbon removal projects. Governments and corporations invest in these projects to meet their own net-zero pledges. The companies then issue carbon credits to the investing entity. Verra has stated that they have issued over 1 billion carbon credits, translating into the reduction of 1 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions. However, countless case studies and reports have indicated that only a small fraction of these funds reach the local communities practising sustainability.

Article 6 under the Paris Agreement further concretised and regulated the crediting mechanism to enable countries interested in setting up carbon trading schemes. However, the parties failed to reach a consensus regarding the specifics of Article 6 at COP 27 and COP 28. So, climate finance experts and policymakers were very interested in the developments taking place at the COP 29 summit in Baku, Azerbaijan. Unlike its predecessors, the COP 29 summit has seen a diminished attendee list, with major Western political leaders including Joe Biden, Ursula von der Leyen, Olaf Scholz, and Emmanuel Macron failing to make it to the summit due to the increasingly turbulent climate within their own constituencies.

From a post-colonial perspective, carbon markets have been viewed as perpetuating existing global hierarchies; wealthier countries and corporations fail to reduce their emissions and instead shift the burden of mitigation onto developing nations. | Photo Credit: Illustration by Irfan Khan

Sceptics questioned whether this iteration of the summit would lead to any substantial decisions being passed. However, on day-two of the summit, parties reached a landmark consensus on the standards for Article 6.4 and a dynamic mechanism to update them. Mukhtar Babayev, the Minister of Ecology and Natural Resources of Azerbaijan and the COP 29 President, said: “By matching buyers and sellers efficiently, such markets could reduce the cost of implementing Nationally Determined Contributions by 250 billion dollars a year.” He added that cross-border cooperation and compromise would be vital in fighting climate change.

India has positioned itself as an advocate for the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDCs) group, with Naresh Pal Gangwar, India’s lead negotiator at COP 29, saying, “We are at a crucial juncture in our fight against climate change. What we decide here will enable all of us, particularly those in the Global South, to not only take ambitious mitigation action but also adapt to climate change.”

The COP 29 decision comes in light of the Indian government’s adoption of the amended Energy Conservation Act of 2022, which enabled India to set up its own carbon market. In July 2024, the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE), an agency under the Ministry of Power, released a detailed report containing the rules and regulations of the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS), India’s ambitious plan for a compliance-based carbon market. The BEE has aimed to launch India’s carbon market in 2026.

CSE’s report highlighted the challenges and possible strategies that the Indian carbon market could adopt from other carbon markets around the world. Referring to this report, Parth Kumar, a programme manager at CSE, pointed out how low carbon prices and low market liquidity would be prominent challenges that the nascent Indian market would have to tackle.

The Global South should be concerned

Following the landmark Article 6.4 decision, climate activists called out the supervisory board for the lack of discussion in the decision-making process. “Kicking off COP29 with a backdoor deal on Article 6.4 sets a poor precedent for transparency and proper governance,” said Isa Mulder, a climate finance expert at Carbon Market Watch. The hastily passed decision reflects the pressure that host countries seem to face; a monumental decision must be passed for a COP summit to be touted as a success.

The science behind carbon markets is rooted in the ability of forests, soil, and oceans to act as carbon sinks by capturing atmospheric carbon dioxide. This process is known as carbon sequestration, and it is central to afforestation and soil health restoration projects. However, the long-term efficacy and scalability of these projects have been repeatedly questioned. The normative understanding of carbon markets as a tool to mitigate climate change has also come under scrutiny recently, with many activists calling the market-driven approach disingenuous to the goals of the climate movement.

From a post-colonial perspective, carbon markets have been viewed as perpetuating existing global hierarchies; wealthier countries and corporations fail to reduce their emissions and instead shift the burden of mitigation onto developing nations. Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, Professor of Philosophy at Georgetown University, said, “Climate colonialism is the deepening or expansion of foreign domination through climate initiatives that exploit poorer nations’ resources or otherwise compromises their sovereignty.” Moreover, the effects of climate change disproportionately fall on the shoulders of marginalised communities in the Global South, even though industrialised nations historically produce the bulk of emissions.

There have also been doubts surrounding the claiming process of carbon credits and whether the buyer country or the country where the project is set can count the project towards its own Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Provisions under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement state that countries cannot use any emission reductions sold to another company or country towards their own emissions targets. However, this has become a widespread issue plaguing carbon markets. The EU has recently been criticised for counting carbon credits sold to corporations under the Carbon Removal Certification Framework (CRCF) towards the EU’s own NDC targets. This has led to concerns over the overestimation of the impact of mission reduction projects.

Also Read | India needs climate justice, not just targets

Carbon offset projects, additionally, alienate local communities from their land as the idea of ownership and stewardship becomes muddled with corporate plans on optimally utilising the land for these projects. For example, in 2014, Green Resources, a Norwegian company, leased more than 10,000 hectares of land in Uganda, with additional land being leased in Mozambique and Tanzania. This land was used as a part of afforestation projects to practise sustainability and alleviate poverty in the area. However, interviews conducted with local Ugandan villagers revealed that the project forcibly evicted the local population without delivering its promises to improve access to health and education for the community. These concerns highlighted how the burden of adopting sustainable practices is placed on marginalised communities.

While carbon markets are rightfully criticised, they remain a key piece of the global climate adaptation puzzle. Addressing the issues surrounding transparency and equitable benefit-sharing with local communities could lead to carbon markets having a positive impact on climate change. The system must ensure that larger corporations and countries do not merely export their emissions, but instead implement measures to reduce their own emissions over time. It is also imperative to explore other innovative strategies such as circular economy approaches and nature-based solutions that are more localised, offering hope for a just and sustainable future.

Adithya Santhosh Kumar is currently pursuing a Master’s in Engineering and Policy Analysis at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands.

Source: frontline.thehindu.com

Related posts:

A new destructive business: Carbon credits from tree plantations

A new destructive business: Carbon credits from tree plantations

East Africa poised to monitor carbon emission

East Africa poised to monitor carbon emission

The Rush for Carbon Concessions: More Land Theft and Deforestation

The Rush for Carbon Concessions: More Land Theft and Deforestation

Uganda: Local communities claim they are not benefiting from Green Resources’ subsidiary’s carbon credit initiative; incl. company’s comments

Uganda: Local communities claim they are not benefiting from Green Resources’ subsidiary’s carbon credit initiative; incl. company’s comments

A decade of displacement: How Uganda’s Oil refinery victims are dying before realizing justice as EACOP secures financial backing to further significant environmental harm.

Carbon Markets Are Not the Solution: The Failed Relaunch of Emission Trading and the Clean Development Mechanism

Govt launches Central Account for Busuulu to protect tenants from evictions

Top 10 agribusiness giants: corporate concentration in food & farming in 2025

Uganda’s top Lands Ministry official has been arrested and charged with Corruption and Abuse of Office, a significant event that will have far-reaching implications for land governance in the country.

A decade of displacement: How Uganda’s Oil refinery victims are dying before realizing justice as EACOP secures financial backing to further significant environmental harm.

Govt launches Central Account for Busuulu to protect tenants from evictions

Environmentalists raise red flags over plan to expand oil palm fields in Kalangala

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

- PRESENDIANTIAL DIRECTIVE BANNING ALL LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA

- FROM LAND GRABBERS TO CARBON COWBOYS A NEW SCRAMBLE FOR COMMUNITY LANDS TAKES OFF

- African Faith Leaders Demand Reparations From The Gates Foundation.

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoA decade of displacement: How Uganda’s Oil refinery victims are dying before realizing justice as EACOP secures financial backing to further significant environmental harm.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoGovt launches Central Account for Busuulu to protect tenants from evictions

-

WITNESS RADIO MILESTONES2 weeks ago

WITNESS RADIO MILESTONES2 weeks agoTop 10 agribusiness giants: corporate concentration in food & farming in 2025

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoCarbon Markets Are Not the Solution: The Failed Relaunch of Emission Trading and the Clean Development Mechanism