WITNESS RADIO MILESTONES

Canada’s Development Finance Institution and Land Grabbing in Africa

Published

3 years agoon

On Wednesday, April 27th, 2022, we caught up with Devlin Kuyek, a researcher at GRAIN, a small international non-profit organization that works to support small farmers and social movements in their struggles for community-controlled and biodiversity-based food systems, and Geoffrey Wokulira Ssebaggala, the Director of Witness Radio Uganda, a not-for-profit national organization which combines both media approaches and legal aid support to mobilize, connect and empower small holder farmers to speak with one voice against land injustices and push for equitable access to opportunities and resources.

This interview is part of a series with the Blended Finance Project a group of unions, non-governmental organizations and academics who are concerned about the Canadian government’s embrace of what is called “blended finance.” We argue that blended finance is merely the latest iteration of the privatization and financialization of foreign aid and seek to engage others in Canada and around the world to propose more equitable public alternatives.

Adrian Murray (AM) and Susan Spronk (SS): In the Blended Finance Project, we have documented how blending uses public money to leverage private money and to shift the risk of investment from the private to the public sector by subsidizing commercial actors. Witness Radio and GRAIN have been supporting communities negatively affected by the very harmful role that unaccountable private equity firms are playing in land grabbing throughout the world, a process which is often facilitated by public development banks and development finance institutions (DFIs). How are blending and other so-called innovative finance mechanisms implicated in these land grabbing deals?

Devlin Kuyek (DK): GRAIN’s focus is on food and agriculture, but blending is a common trend unfolding in multiple sectors. In many countries in the global South, food systems are still largely in the hands of small-scale food producers: farmers, pastoralists, fisher folk. Markets are managed and controlled by small vendors. These food systems do a great job of providing people with nutritious food. They’re sustainable and they’re low emission. But they do not serve the interest of corporations because there’s no room there for corporations to profit. These are the kinds of growth areas where multinational food and agribusiness corporations and financial firms are looking to grow, that is, ‘frontier markets’. Some corporations call this initiative ‘digging into the pyramid;’ the bottom of the pyramid, where most people are.

Now in these areas investment is not so easy: there are difficulties with infrastructure, land conflicts, etc. Expanding agribusiness there involves dispossessing people from their land. It’s risky from a corporate point of view, and they have more difficulties attracting finance to move into these areas. The development banks play a key role in providing that kind of investment, which is where they come in. They’ll provide loans or even equity investments in some of these companies that are operating in these ‘frontier areas’, that provides a bit of a guarantee to other investors who might come in via pension funds or other institutional investors. So, development banks actually play a major role in expanding agribusiness into these areas and that’s why they’re so involved in land grabbing, in the destruction of local markets and all kinds of other conflicts that we see.

Geoffrey Wokulira Ssebaggala (GWS): This kind of development creates a lot of conflict. I’ve just returned from court in the countryside, Kiryandongo in Uganda. For the last two years we’ve been pushing and supporting civil court cases that were filed by communities that are being forcefully evicted by multinational agribusiness companies – American, Indian and many others. We are happy that the cases are finally being heard. It’s been a long struggle.

AM and SS: Canada established a development finance institution called FinDev in 2017 headquartered in Montreal, Quebec. What has been the track record of FinDev thus far?

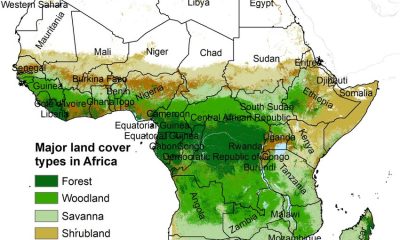

DK: I’ve looked mainly at their investments in Africa in the food sector. This sort of ‘new’, innovative financing institution is, interestingly enough, involved in old colonial style projects: several of their investments are involved in plantations on large areas of land.

One of FinDev’s investments is in a company called Miro Forestry, which has large-scale industrial tree plantations on 21,000 hectares in Sierra Leone and 10,000 hectares in Ghana. In both instances there are land conflicts with local communities. In Sierra Leone, the contracts that they signed for the leases over the lands stipulate that the company pays the communities only two dollars per hectare, per year for this loss of their lands. With these deals, communities lose their ability to gain livelihoods from these areas. Miro Forestry establishes tree plantations, so there’s very little job creation. The communities are saying that the company has not lived up to even the meager promises they made: to build schools, to provide social services, decent jobs, etc. These areas are now fenced off so that communities have trouble accessing the water sources and other resources that they used to have access to. They have difficulty even accessing the road that cuts through the area. In Ghana, there are similar complaints: lack of consultation; people’s crops were destroyed when the company moved in and took over the lands, etc.

By building these tree plantations, the company is also selling carbon credits. These deals allow some of the worst polluters on the planet to purchase carbon credits so they can keep on polluting. It is part of their business model. This form of ‘development’ thus involves taking away the land and resources that people could have for local food production in countries that will be hardest hit by the climate crisis. The local communities become dependent on food imports. And the profits go mainly to foreign investors that are involved.

DFIs are also investing in private equity funds. This is a growing trend in Africa and elsewhere where you see private equity companies established through offshore structures, operating through tax havens, who charge huge management fees. One particular fund that FinDev is invested in is managed by Phatisa, a company based in Mauritius. They have these fee structures whereby a large portion of whatever profits come out of this end up with the fund managers. They also seek very high returns so the investments that are being made by these development banks through them are seeking high returns in food and agriculture in Africa, meaning they’re extracting a lot of the wealth that could be generated from food and agriculture on the continent and taking it out of the countries and the continent. They’re also invested in some large, multinational food and agribusiness corporations like the Export Trading Group. It’s hard to understand why the Canadian government is providing a subsidized form of finance to a multinational corporation in order for it to expand into Africa in this way.

AM and SS: Turning to the effects of blending on local communities, can you tell us why it’s been so difficult for communities that you work with and others to hold these development finance institutions accountable?

GWS: We have been trying to establish whether FinDev is active in Uganda, but we do not know.

It is difficult to get information about who is funding what never mind holding the companies and institutions involved accountable. Our experience is that neither the development finance institutions, nor the companies and private equity firms that they finance, engage with local communities from the word ‘go’. Local communities don’t decide which projects they should have. These institutions do not seek community consent regarding what projects take place on their land. It is a very violent process. People lose everything from their livelihoods to social well-being because of these investment projects.

In the Ugandan context, the field of investment is marred with a high level of corruption. Information about investment is hidden from communities until organizations like Witness Radio, GRAIN and a few others do background checks to establish where the money is coming from to evict these communities. And, of course, the journey to get a remedy, is not an easy journey. Internal accountability mechanisms, take a lot of time. Resorting to domestic courts is another horrible experience one can talk about. So, yeah, there is a lot that really needs to be done.

DK: Development banks like to portray themselves as being held to a higher level of environmental and social governance standards. Some of them even have grievance mechanisms in place. Our experience is that these do nothing to address the huge power imbalance that exists between the companies they invest in, who are very often closely aligned with local elites, and the marginalized communities where they operate and are taking land.

Take the case of Feronia. It’s a Canadian-based company traded on the public stock exchange – now bankrupt – but operating oil palm plantations on over 100,000 hectares of land in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. For years and years, communities issued statements and memorandums, documented human rights abuses, environmental violations and egregious labor violations, thereby exposing many illegalities when it came to the land occupation. And the development banks, who actually had majority control of this corporation for several years, did nothing but parrot the words of the executives who were not even based locally. There was no serious effort to investigate the actual allegations that were being made.

It came to a point where a grievance was filed for a mediation process by 11 of the affected communities, which was accepted by the international complaints mechanism of the German and Dutch development banks (the French development bank is also now part of it). That process has dragged on for three years now. In the midst of that process the development banks exited entirely, handing the company over to a private equity fund. It was just completely unaccountable to anyone. The reports coming out of human rights abuses remain as egregious as ever, but this complaint mechanism now has very little teeth. So even in a best-case scenario where there is a grievance process, there is almost no accountability.

AM and SS: Given what you’ve told us about DFIs, including FinDev Canada, what would you argue: should these institutions be reformed or just abolished. And if abolished, what would you like to see in their place? What do we need?

DK: Well, our focus is on food and agriculture. Development finance is fundamentally about providing more investment and finance. It’s about channeling money, more money. A lot of it going toward the expansion of corporate agribusiness. It’s structured in a way that makes it impossible to imagine how that money could go towards funding agroecology, land redistribution, the functioning of smallholder markets and local food systems, farmer seed systems. FinDev is about creating the sort of corporate profit structures and industrial agricultural models of production that have nothing to do with the needs and interests of local communities, which is supposed to be what these funds are set up to do.

Development finance institutions like FinDev are, in a sense, a colonial holdover, and that’s why they fund things like plantations. After 300 years of experience with plantations, it’s very difficult to imagine how any institution concerned with development could think that that would be an appropriate investment and yet that’s what they’re committed to and doing. So, in our view, we don’t need more of these development banks. They should be abolished. That’s not where public money should be going.

If Canada and other countries are interested in supporting different systems that that are able to deal with the climate crisis, that are able to get over some of the systemic and structural issues that are the cause of poverty and that are plaguing local communities, so that their needs are actually met, we need a totally different mechanism. And those mechanisms should be in some way accountable to the people that they are supposed to be serving. At a minimum, such a mechanism requires a governance structure with a very strong voice and representation within the decision-making for the communities that they’re supposed to be serving. We are very far from that now.

GWS: I don’t know how best we can reverse this. First, we need development finance institutions and banks to accept the mistakes that they’ve made and then they need to come up with clear, straightforward plans on how they are going to fix these problems.

Second, there must be close supervision and monitoring of where the money has been pumped into, and what it’s doing. Institutions and investors must follow due process. Because they seem to claim that they follow environmental protections, human rights protections and many other things, they do not have a clear plan for monitoring where the money goes. Monitoring and enforcement needs to happen from day one.

Third, we need development banks to bring real development. If the majority of local communities continue to lose their land to investors, people will target those international investments with demonstrations and strikes. And therefore, there’s no sustainable future for these kinds of investments that operate in countries like Uganda. Doing meaningful, responsible business should be the starting point if they want to protect their investments and also their profits.

AM and SS: A statement that was signed by over 80 civil society organizations issued in October of 2021 in advance of the Finance in Common Conference on Agriculture that was being organized by the public development banks states the following: “we call for the creation of a fully public and accountable funding mechanisms that support people’s efforts to build food sovereignty realize the human rights of food, protect and restore ecosystems and address the climate emergency.” What does this funding mechanism look like? Can you provide an example?

GWS: It’s very difficult right now to determine or define how best this should be done. Right now we are strategizing on how best to make the current financial actors accountable to communities. In Uganda we in communities can’t rely on the government. They have disappointed us. But nor can we trust the financiers, because they’ve taken away our land our livelihoods. It’s a mess.

DK: I don’t think there’s one existing case that would match with the ideal articulated in the statement. But, it is still a vision worth striving for. As Geoffrey notes, most governments do not seem interested.

Instead, governments are involved in the current push towards blended finance. Blended finance is all about ensuring that any state project is ultimately backed by people, so we have the final responsibility for it. But it’s our money. The risk is all taken by the government and the people. And the private sector has control and makes the profits.

With blended finance, development finance is making an already atrociously corrupt situation even worse. More money is not going to resolve this problem. So, there is certainly a need for international solidarity. Right now, the context is so toxic and corrupt that the real thing that we need to do as Canadians right now is to make sure that there is no way that any public money in our name goes to make matters worse for people on the ground.

There’s a great photo that Witness Radio took in Kiryandongo that captures what the development finance model is accomplishing right now. You see a tractor from the company which has received money from a development bank, after a forceful eviction of the people, plowing up their cassava crop, which is a very sustainable, important local crop. They’re destroying it in order to be able to plant corn or maize or soybeans for export.

Whatever shape this new, public, accountable finance mechanism takes, whether a government program, bilateral aid or some kind of small grant fund that is able to support communities, the fund needs to be accountable to the local people, be respectful of their control over their land, resources and territories. We need to build from these principles and demand that our governments create such mechanisms. •

Adrian Murray is a SSHRC post-doctoral fellow at the University of Johannesburg researching labour and social movement opposition to the neoliberal restructuring of public services.

Susan Spronk teaches international development and global studies at the University of Ottawa.

Original Source: Socialistproject.ca

Related posts:

Development finance for Covid-19 crisis should uphold human rights

Development finance for Covid-19 crisis should uphold human rights

CSOs urge banks and other IFIs not to finance E.Africa oil pipeline project…

CSOs urge banks and other IFIs not to finance E.Africa oil pipeline project…

Signs of harmful projects with financing from development institutions are spotted in Uganda…

Signs of harmful projects with financing from development institutions are spotted in Uganda…

Africa Development Bank creates $10 bn fund for virus aid

Africa Development Bank creates $10 bn fund for virus aid

You may like

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Young activists fight to be heard as officials push forward on devastating project: ‘It is corporate greed’

Published

3 months agoon

August 27, 2025

“We refuse to inherit a damaged planet and devastated communities.”

Youth climate activists in Uganda protesting the East African Crude Oil Pipeline, or EACOP, are frustrated with the government’s response to their demonstration as the years-long project moves forward.

According to the country’s Daily Monitor, youth activists organized with End Fossil Occupy Uganda took to the streets of Kampala in early August to protest EACOP. The pipeline, under construction since about 2017 and now 62 percent complete, is set to transport crude oil from Uganda’s Tilenga and Kingfisher fields through Tanzania to the Indian Ocean port of Tanga by 2026.

Activists noted the devastating toll, with group spokesperson Felix Musinguzi saying that already around 13,000 people “have lost their land with unfair compensation” and estimating that around 90,000 more in Uganda and Tanzania could be affected. End Fossil Occupy Uganda has also warned of risks to vital water sources, including Lake Victoria, which it says 40 million people rely on.

The group has been calling on financial institutions to withdraw funding for the project. Following a demonstration at Stanbic Bank earlier in the month, 12 activists were arrested, according to the Daily Monitor.

Some protesters were seen holding signs reading “Every loan to big oil is a debt to our children” and “It’s not economic development; it is corporate greed.”

Meanwhile, the regional newspaper says the government has described the activist efforts as driven by foreign actors who mean to subvert economic progress.

EACOP’s site notes that its shareholders include French multinational TotalEnergies — owning 62 percent of the company’s shares — Uganda National Oil Company, Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation, and China National Offshore Oil Corporation.

The wave of young people taking action against EACOP could be seen as a sign of growing public frustration over infrastructural projects that promise economic gain while bringing harm to local communities and ecosystems. Activists say residents face costly threats from pipeline development, such as forced displacement and the loss of livelihoods.

Environmental hazards to Lake Victoria could also disrupt water supplies and food systems, bringing the potential for both financial and health impacts. Just 10 years ago, an oil spill in Kenya caused a humanitarian crisis. The Kenya Pipeline Company reportedly attributed the spill to pipeline corrosion, which led to contamination of the Thange River and severe illness.

The EACOP project has already locked the region into close to a decade of development, and concerns about the pipeline and continued investments in carbon-intensive systems go back just as long. Youth activists, as well as concerned citizens of all ages, say efforts to move toward climate resilience can’t wait. “As young people, we refuse to inherit a damaged planet and devastated communities,” Musinguzi said, per the Monitor.

Source: The Cool Down

Related posts:

Put people above profits – Climate Activists urge Total to defund EACOP

Put people above profits – Climate Activists urge Total to defund EACOP

EACOP: The number of activists arrested for opposing the project is already soaring in just a few months of 2025

EACOP: The number of activists arrested for opposing the project is already soaring in just a few months of 2025

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

The East African Court of Justice fixes the ruling date for a petition challenging the EACOP project.

The East African Court of Justice fixes the ruling date for a petition challenging the EACOP project.

WITNESS RADIO MILESTONES

Why matooke farming is losing ground in Bukedi

Published

3 months agoon

August 27, 2025

On a humid morning in Namusango Village, Kamonkoli South Ward, Kamonkoli Town Council in Budaka District, 58-year-old farmer James Kainja walks at the edge of what used to be his flourishing matooke garden. For generations, the green banana plant—matooke—stood tall in Uganda’s farmlands, its broad leaves swaying in the wind and its heavy bunches promising a warm, hearty meal. But in Bukedi Sub-region today, that story is fading. Between the tired banana stools, spear grass has taken over. A few bunches hang small and low quality. “We used to harvest every week,” Mr Kainja says, dusting his palms.

“Now, it is once in a while and the money is not worth the struggle,” he adds. Across Bukedi, particularly in Pallisa, Budaka, Butebo, and Kibuku, the banana plants are shrinking back, replaced by maize, cassava, rice, and other faster-growing crops. The sub-region that once sent truckloads of matooke to nearby districts now measures its banana harvest in small piles under tarpaulin. Where the green canopy of banana leaves once dominated, the landscape has changed. For many farmers, the decision is not about abandoning tradition but about survival.

Matooke as culture

In many Bukedi households, matooke still holds cultural value, especially during weddings, funerals, and community gatherings. But with fewer plantations, sourcing enough bunches has become harder and more expensive. Matooke is now imported into Bukedi from Mbale and Mbarara. Mr Abubakar Nanghejje, an elder in Kibuku, warns: “If this trend continues, our children may only know matooke from stories. We are losing more than a crop—we are losing a piece of who we are.”

He adds that matooke, once abundant, is now a luxury: “People only access matooke during ceremonies because the cost of a bunch has turned expensive,” he explains. Within Kibuku Town Council, women sell matooke in pieces: three or four fingers for Shs1,000, while a complete bunch costs between Shs30,000 and Shs35,000. This contrasts sharply with central and western Uganda, where matooke is more than a crop—it is an identity, a culture, and a livelihood. Yet across the country, banana plantations are thinning out, replaced by maize, beans, or simply abandoned.

Farmers’ voices

Mr Peter Mwigala, a 73-year-old farmer from Bubulanga Village, recalls with nostalgia: “I grew matooke for 30 years. But now my plantation is less than half what it used to be. The pests are too many, the prices are too low, and the rains are no longer reliable.” His story echoes across villages, evidence of a slow, steady decline in matooke production. This decline has unfolded over two to three decades, rather than as a sudden collapse. Agricultural researchers point to several reasons. Among them, banana bacterial wilt (BBW), banana weevils, and nematodes that have devastated plantations in major banana-growing areas. These pests cause premature ripening, rotting, and eventual uprooting of infected plants.

“When wilt enters your plantation, you can lose everything in one season,” says Mr Abner Botiri, an agriculture officer in Budaka. He further explains that erratic rainfall and prolonged dry spells also take a toll. Matooke thrives in consistent moisture, but under drought stress it yields smaller bunches. Repeated losses have led some farmers to abandon the crop entirely. Continuous cultivation without soil management has also depleted many banana-growing soils. Beyond agronomic challenges, the economics of matooke farming have shifted dramatically. Local market prices fluctuate widely depending on supply, while transport costs have risen sharply.

Mr John Gwanyi, a 71-year-old farmer, recalls: “In the 1980s and 1990s, matooke farmers could educate children through primary, secondary, and tertiary levels, and still cover basic needs. Today, a whole plantation might not pay for one term’s school fees.” Urbanisation has worsened the trend. Younger generations moving to towns now eat rice, spaghetti, and bread more frequently.

The once sacred matooke meal is no longer the undisputed centrepiece of Ugandan dining tables. Meanwhile, land fragmentation leaves families with smaller plots, unable to sustain large banana plantations. In some areas, higher-value or quicker-return crops like coffee, passion fruit, or maize dominate. As one agricultural economist notes: “A bunch of matooke takes nine months to mature, but maize can be ready in three months. For cash-strapped farmers, that difference matters.

Government interventions

Government and research institutions have made several attempts to address the situation. The National Agricultural Research Organisation (NARO) has introduced resistant banana varieties and promoted good agronomic practices. NGOs are training farmers in mulching, proper spacing, and integrated pest management. Still, the decline carries a cultural weight. In Buganda, for instance, matooke is central to marriage ceremonies, community gatherings, and daily life.

“When you serve matooke at a function, it shows respect,” explains Mr Badiru Kirya, a cultural leader in Obwa Ikumbania bwa Bugwere. Yet, Mr Kirya attributes part of the decline to newer banana varieties introduced by research agencies. “The old varieties planted by our grandparents could withstand weather changes better. These new varieties are weaker against climate volatility,” he says. He also notes that soil infertility and population pressure have accelerated the decline, as families squeeze more onto smaller pieces of land.

National standing

Uganda remains one of the world’s largest banana consumers, with per capita consumption estimated at 250–300 kg annually in some regions. Yet, national banana production has generally declined. According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) 2024 census, only 27.1 percent of households participate in banana cultivation. Dr Sadik Kassim, the NARO deputy director general in-charge of agricultural promotion, highlights several factors. “Soil fertility has gone low, while pests and disease build-up have grossly affected matooke gardens. Erratic rainfall and climate change further reduce yields.

Poor agricultural practices have made the decline worse,” he says. However, Dr Kassim dismisses the claim that new technologies are to blame. Similarly, Dr Rabooni Tumuhimbise, the director of research at Rwebitaba Zonal Agricultural Research and Development Institute, said: “As of now, I am not aware that Bukedi has registered a decline in banana production. This needs verification before conclusions.” But farmers and local leaders insist the reality is clear: matooke is disappearing from Bukedi. Mr Arthur Wako Mboizi, a seasoned politician and opinion leader, argues: “Bukedi has drastically registered a total decline in banana production due to various factors, including soil infertility, diseases, and erratic rainfall.”

Efforts are underway to add value. Under the Presidential Initiative on Banana, NARO and Kilimo Trust have developed matooke-based products such as flour, bread, and cakes. More than 13 million Ugandans consume bananas as their staple, and 75 percent of farmers grow them, contributing nearly $440 million annually to the economy. Yet, for Bukedi, the reality is sobering. The once proud producer of matooke is a shadow of its former self. As Mr Nanghejje, the Kibuku elder, put it: “We are losing more than a crop. We are losing a piece of who we are.”

Background

In 2024, national banana production was estimated at 6 million tonnes annually, 70 percent of which was consumed at household level and 30 percent sold.

The Banana Merchandise Trade Statistics Bulletin (2024) shows export earnings rose from $2.1 million in June 2023 to $2.4 million in June 2024. Still, yields remain below potential—currently 5–30 tonnes per hectare compared to an attainable 60–70 tonnes. Uganda’s banana losses to wilt disease are massive, with officials estimating a 71.4 percent loss of potential harvest annually, worth nearly $300 million.

Source: Monitor

Related posts:

Govt injects Shs47b into cassava growing in Bukedi

Govt injects Shs47b into cassava growing in Bukedi

Uganda’s natives are becoming more powerless; losing land everyday, says a New Research Report

Uganda’s natives are becoming more powerless; losing land everyday, says a New Research Report

Omoro farmers task Naro on crop varieties

Omoro farmers task Naro on crop varieties

Uganda losing agricultural advantage to neighbours – UN.

Uganda losing agricultural advantage to neighbours – UN.

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Cases against anti-EACOP activism are skyrocketing in Uganda. Witness Radio has documented close to 60 cases in the last eight months.

Published

4 months agoon

August 7, 2025

By the dedicated efforts of the Witness Radio team.

The Witness Radio team has documented nearly 60 cases of arrest, detention, and prosecution targeting activists protesting the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) since January 2025.

The $5 billion EACOP project, led by TotalEnergies and its partners, involves the construction of a 1,444km heated pipeline from Hoima in Uganda to Tanga in Tanzania. This pipeline, which will transport crude oil from the Tilenga and Kingfisher fields, has been a subject of controversy due to its potential environmental and social impacts.

As activism against the EACOP Project grows in Uganda, youth activists leading the cause face strong resistance from the government and its agents, who are pushing for the development of oil activities, including EACOP. Their bravery in the face of such adversity is truly inspiring.

The activists have continuously been suppressed and weakened with torture, unlawful arrests, and prolonged detentions accompanied by unscrupulous charges. The injustice they face is a call for empathy from all who hear their story.

The latest incident happened on Friday, August 1, 2025, when the police brutally arrested 12 environmental activists at Stanbic Bank Headquarters in Kampala. The urgency of the situation is apparent, as the activists were protesting against the bank’s financing of the EACOP project.

On March 26, 2025, EACOP Ltd., the company in charge of the construction and future operation of the EACOP project, announced new project financing from regional banks such as Stanbic Bank Uganda Limited, KCB Bank Uganda, African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), the Standard Bank of South Africa Limited, and the Islamic Corporation for the Development of the Private Sector (ICD). The announcement sparked widespread alarm and outcry, with activists urging the banks to immediately withdraw their support and halt the financing of the project.

These activists, individuals from Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) and environmental enthusiasts, strongly oppose the implementation of the EACOP project. They cite its harmful effects, including the displacement of thousands of people, damage to sensitive ecosystems, a threat to water resources, and exacerbating climate change mainly through carbon emissions. They argue that the short-term economic benefits do not justify these long-term consequences.

In doing their work, they have ended up in the hands of the authorities with numerous charges slapped against them. The latest remandees include Teopista Nakyambade, Shammy Nalwadda, Dorothy Asio, Shafik Kalyango, Habibu Nalungu, Noah Kafiiti, Ismael Zziwa, Ivan Wamboga, Akram Katende, Baker Tamale, Keisha Ali, and Mark Makobe.

On the same day of their arrest, the victims were arraigned before the Buganda Road Chief Magistrate Winnie Nankya, who charged them with common nuisance. She later remanded them to Luzira prison until August 18, 2025.

Section 160 of the Penal Code Act, Cap 120 states that a person convicted of common nuisance faces a one-year imprisonment.

In response, the Stanbic Bank manager for corporate communications, Mr. Kenneth Agutamba, confirmed that the bank is financing the EACOP project, justifying that it aligns with and balances environmental sustainability and economic development in the country.

Ever since this year started, Witness Radio has documented 56 cases of arrests and illegal detentions of EACOP activists, with most of them being charged with common nuisance. Below is a chronology of these incidents as they happened.

| Date | Incident | Charge |

| 26th Feb. 2025 | 11 activists were arrested while marching to the European Union offices deliver a petition concerning TotalEnergies’ involvement in harmful fossil fuels in Uganda. | Common nuisance |

| 19th Mar. 2025 | 4 activists were arrested while marching to the Parliament of Uganda to deliver a petition to the speaker, Anita Annet Among, in protest of the ongoing construction of the EACOP Project. | Common nuisance |

| 2nd April, 2025 | 9 activists were arrested while marching to Stanbic bank offices. | Common nuisance |

| 23rd of April, 2025 | A group of 11 activists were arrested as peacefully went to deliver a petition to KCB Uganda offices challenging its will to fund the EACOP project. | Criminal trespass. |

| 21 May 2025 | 9 activists arrested while protesting KCB financing of the EACOP | Common nuisance. |

| 1 Aug. 2025. | 12 activists arrested for protesting the Stanbic bank funding. | common nuisance |

According to Witness Radio’s special report, “Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP Protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems,” released last month, a case review revealed that while Uganda’s justice system is being used to suppress the activities of youth activists opposing the EACOP project, many of these cases have lacked merit and were ultimately dismissed.

The report found that none of the activists had been convicted, though they continue to face prolonged court processes marked by repeated adjournments. “Of a sample of 20 documented cases since 2022 involving the arrest of over 180 activists, 9 case files have either been dismissed by the courts or closed by the police due to lack of prosecution, another signal indicating the relevance and legitimacy of their work, while 11 cases remain ongoing,” the report noted.

Related posts:

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

Breaking: over 350,000 acres of land were grabbed during Witness Radio – Uganda’s seven months ban.

Breaking: over 350,000 acres of land were grabbed during Witness Radio – Uganda’s seven months ban.

EACOP: The number of activists arrested for opposing the project is already soaring in just a few months of 2025

EACOP: The number of activists arrested for opposing the project is already soaring in just a few months of 2025

Crackdown on EACOP protesters intensifies: 35 Activists arrested in just four months.

Crackdown on EACOP protesters intensifies: 35 Activists arrested in just four months.

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

Environmentalists reject TFFF, warning it will deepen forest destruction.

“Vacant Land” Narrative Fuels Dispossession and Ecological Crisis in Africa – New report.

Uganda’s Army is on the spot for forcibly grabbing land for families in Pangero Chiefdom in Nebbi district.

Seed Boot Camp: A struggle to conserve local and indigenous seeds from extinction.

REC25 & EXPO Ends with a call on Uganda to balance conservation and livelihood

“Vacant Land” Narrative Fuels Dispossession and Ecological Crisis in Africa – New report.

Report reveals ongoing Human Rights Abuses and environmental destruction by the Chinese oil company CNOOC

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

- PRESENDIANTIAL DIRECTIVE BANNING ALL LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago“Vacant Land” Narrative Fuels Dispossession and Ecological Crisis in Africa – New report.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days agoActivists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoUganda’s Army is on the spot for forcibly grabbing land for families in Pangero Chiefdom in Nebbi district.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoSeed Sovereignty: Most existing and emerging laws and policies on seeds are endangering seed saving and conservation on the African continent.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoEnvironmentalists reject TFFF, warning it will deepen forest destruction.

-

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks agoDiscover How Foreign Interests and Resource Extraction Continue to Drive Congo’s Crisis

-

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks agoAfrica’s Land Is Not Empty: New Report Debunks the Myth of “Unused Land” and Calls for a Just Future for the Continent’s Farmland

-

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks agoClimate wash: The World Bank’s Fresh Offensive on Land Rights