MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Published

3 weeks agoon

By Witness Radio team

Uganda has experienced persistent land evictions for decades. However, some actors are increasingly deliberating on how to ensure people have land tenure security. As the country heads into another general election on Thursday, the 15th of this month, land has once again emerged as one of the most emotionally charged and politically sensitive issues during the campaigns.

From the Kiryandongo land grabs involving multinational companies to the Amuru land wrangles, and from Bunyoro’s oil-rich fields to increasing evictions in the Buganda (Central) sub-region of Uganda, stories of land grabbing and displacement continue to dominate public debate and news headlines, especially during presidential campaigns. Every election season brings renewed promises from political actors to end land injustice.

According to the 2024 Police Annual Report, 397 land-related criminal cases were recorded, up from 271 in 2023, underscoring the urgent need for systemic solutions to address this escalating crisis.

Land grabbing in Uganda often leaves communities landless and powerless, which should evoke empathy and motivate the citizenry to seek justice and systemic change.

Mr. Ulama Dison Duke Ukerson will take decades to forget how his land, which he invested all his savings in, was forcibly seized by the Uganda Peoples’ Defense Forces (UPDF), a national army.

“The UPDF has taken over my land. They occupied it and are now using my six buildings. I had constructed them for my piggery and poultry farming project on my five acres of land,” he revealed in an interview with Witness Radio.

The chief is among hundreds of people in the Koch community living in distress after the alleged grabbing of clan land by the Uganda Army in March 2020, which seized approximately 100 acres of land used by the community for over 150 years without consultation or compensation, illustrating the widespread injustice faced by vulnerable communities.

“People are suffering, and no one has compensated us. We just woke up one day to see the army forcefully taking our land. I first heard about the soldiers’ presence from the chairman. By then, they had already broken into my manager’s house,” he added.

Although he is the traditional chief of the Pangero Clan, this did not stop those in power from grabbing his land. The land taken covers three villages: Aleikra, Kochi Central, and Panyabongo in Koch Parish, Nebbi District, belonging to the Pangero clan. Despite the years passing by, the Pangero Chiefdom remains in uncertainty and hardship.

Across Uganda, many communities face evictions, and presidential candidates’ acknowledgment of this nationwide concern can inspire Ugandans to use this opportunity to push for concrete actions and hold leaders accountable for real change.

Manifestos full of promises.

Major political parties contesting for power acknowledge the gravity of the land crisis and have placed solving the problem prominently in their manifestos. Other aspirants have promised not only to stop land grabbing but also to reinstate displaced people on their land.

The Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) promises legal reforms, including a review of the Constitution and the Land Act, simplified registration of customary land, stricter controls on notable land titles, faster resolution of land cases in courts, enforcement of women’s land rights, and harmonization of land and environmental laws.

The National Unity Platform (NUP) frames land grabbing as a human rights and governance crisis driven by elite capture, foreign investment, and intimidation. Its manifesto proposes restoring land to rightful owners, establishing a National Customary Land Registry, subsidizing Certificates of Customary Ownership, protecting Mailo land tenants, preventing politically connected land grabs, and introducing blockchain-based land registration.

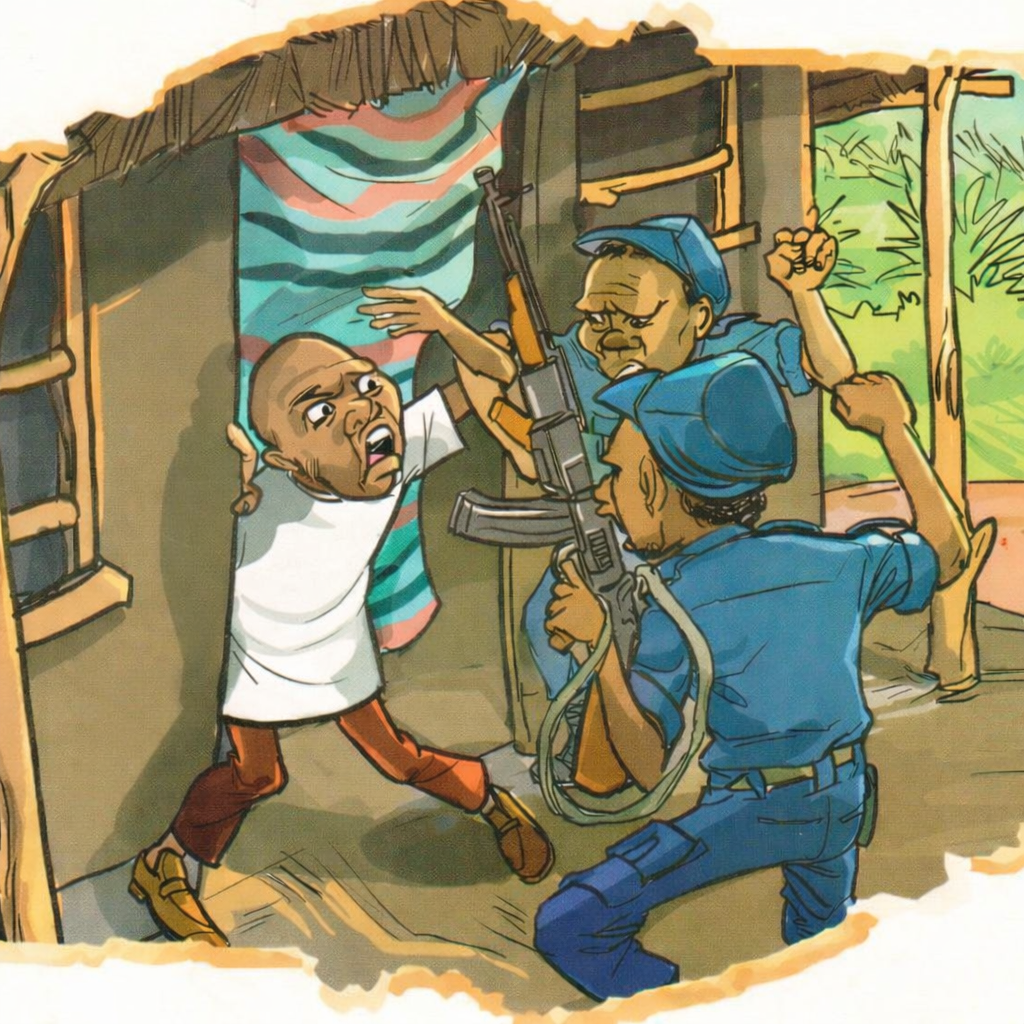

Under the current regime, land evictions continue to escalate. Many alleged land grabbers are power-connected. Other persistent challenges in the land sector include double titling, disregard for laws, court orders, and directives, and multiple offices issuing conflicting instructions that they lack the capacity or will to enforce. One of the most uncomfortable truths in Uganda’s land crisis is the involvement of security agencies in evictions. Police, private security companies, and military personnel are frequently deployed during land disputes, often siding with investors or landlords against vulnerable communities.

Although the Minister of Lands, Judith Nabakooba, has issued several directives barring security agencies other than the police from enforcing land evictions, these orders are not implemented.

Despite the challenge posed by this problem, the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) has also proposed measures in its manifesto, building on existing programs. These include mass land titling, expansion of the Land Fund, issuance of Certificates of Customary Ownership and occupancy certificates, investigations into multiple titling, action against illegal evictions, use of technology, and faster land transactions.

Will the next Government break the cycle?

Despite well-articulated promises, many believe that systemic enforcement failures-such as corruption, impunity, and lack of political will-are the main drivers of ongoing land grabbing, underscoring the need for accountability to motivate action.

Uganda does not lack land laws or policies; what it needs is more vigorous enforcement and protection for the vulnerable, which should motivate the audience to demand action and accountability.

“If you observe the proposals by NRM, which is in power, NUP, which is not in power, and FDC or any other political aspirant, they are all largely structural and administrative. They all point to behavioral change. NRM continues to promise solutions to problems; it already has the authority to solve,” Land rights expert, Mr. Jimmy Ochom told Witness Radio.

Mr. Ochom, who has worked in the land sector for over 10 years, argues that existing laws are sufficient if properly implemented.

“If we followed what the Constitution, the Land Act, and the National Land Policy provide, we would not be facing this crisis. The problem is implementation. That is the truth. That’s why I get frustrated when new land laws are proposed. We already have adequate legal frameworks,” he said.

According to Ochom, the missing link is accountability, particularly for those in power.

“Land grabbing in Uganda rarely involves ordinary citizens. It often includes politically connected individuals, senior security officers, influential business interests, and complicit land officials. It involves a lot of forces and money, which a poor person cannot afford,” he added.

Emerging technology.

Both NUP and NRM propose using blockchain and digital systems to secure land records. While these tools can enhance transparency, land rights advocates should remain cautious about over-reliance on technology alone, as political will and enforcement are crucial for real change, warns Ochom.

“Digitizing land records doesn’t fix corruption by itself. If the underlying titles are fraudulent and political and legal systems are weak, technology may make injustice faster, more credible, and harder to challenge.”

Breaking the land-grabbing cycle requires accountability across all sectors, not just better land laws, political promises, or election-time excitement. If land continues to be politicized and accountability avoided, the situation will remain unchanged; leaders will enjoy the benefits of office while citizens who voted for them continue to suffer evictions and dispossession.

“I am wondering where my people are going to live. Why should a sane government do this to its subjects?” the traditional clan chief questioned.

Related posts:

Church of Uganda’s call to end land grabbing is timely and re-enforces earlier calls to investigate quack investors and their agents fueling the problem.

Church of Uganda’s call to end land grabbing is timely and re-enforces earlier calls to investigate quack investors and their agents fueling the problem.

Land actors warn of looming violent conflicts due to escalating land grabbing in Sebei and Bugisu sub-regions.

Land actors warn of looming violent conflicts due to escalating land grabbing in Sebei and Bugisu sub-regions.

Archbishop Kazimba Condemns Land Grabbing, Urges Govt to Act

Archbishop Kazimba Condemns Land Grabbing, Urges Govt to Act

Land and environmental rights defenders, CSOs, scholars, and government to meet in Kampala to assess Uganda’s performance on the implementation of the UN Guiding principles on Business and Human Rights in Uganda.

Land and environmental rights defenders, CSOs, scholars, and government to meet in Kampala to assess Uganda’s performance on the implementation of the UN Guiding principles on Business and Human Rights in Uganda.

You may like

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

The Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network Joint Radio program boosts Farmers’ knowledge of seed and food sovereignty.

Published

12 hours agoon

February 4, 2026

By Witness Radio team

Across Africa, seed laws are increasingly structured to favor commercial seed systems, leaving smallholder farmers with limited control over the seeds they rely on for food production. While governments often justify these laws as necessary for quality control and increased productivity, farmers and civil society organizations argue that they deepen dependency, erode Indigenous knowledge, and undermine food sovereignty.

Smallholder farmers produce the majority of the world’s food. Recognizing practices such as saving, exchanging, and replanting seeds can empower farmers and reinforce their vital role in food security.

In response to this challenge, Witness Radio, in partnership with the Seed Savers Network (SSN) in Kenya, is joining hands to save African indigenous seeds by using media to build power and share knowledge and skills with smallholder farmers across Africa and beyond on seed sovereignty and farmer-led food systems.

Last Thursday, Witness Radio and the Seed Savers Network aired the first episode of the program live, featuring representatives of smallholder farmers and civil society organizations from across the African continent. The discussion, which was live on Witness Radio, focused on sharing Indigenous knowledge and practical approaches to saving and conserving African Indigenous seeds.

“It is a crucial time to speak about food sovereignty because, as Indigenous People, talking about food sovereignty is not just an agricultural issue, according to us. It’s a vital act of decolonization and a sign of cultural survival to us and also self-determination.” Said June Bartuin, the Executive Director for Indigenous Peoples’ for peace and climate justice, Kenya, during the first episode of the program.

Across Africa, several policies and laws restrict farmers’ rights to save, exchange, and sell their own seeds. In East Africa, the recently introduced EAC Seed and Plant Varieties Draft Bill 2025 has sparked protests from smallholder farmers and activists, who argue that some of its provisions threaten farmer-led seed systems and favor multinational seed companies.

In Ghana, the Plant Variety Protection Act of 2020 restricts farmers’ seed management practices, underscoring the urgent need for policy reforms that support farmer-led seed systems.

“We have this Plant Variety Protection Act of 2020, which has made it easier for seed companies and the commercial sector to control the seed system,” said Atim Robert Anaab, who works with Trax Ghana and the Beela Project in Northern Ghana, adding that, “The law requires seeds to be certified according to standards that most small-scale farmers simply cannot meet.”

Such laws have reshaped Africa’s food systems by pushing farmers toward commercial seeds that must be purchased every planting season. These seeds are often sold alongside chemical fertilizers and pesticides, significantly increasing production costs for smallholder farmers.

Priscilla Nakato, Chairperson of the Informal Alliance of Communities Affected by Irresponsible Land-Based Investments in Uganda, noted that these policies have also displaced traditional storage and seed preservation practices.

“In the past, every household had a granary, used not only to store food but also to preserve seeds for the next planting season. Many communities still hold this resilience, and reviving these practices can inspire hope for food sovereignty.”

Beyond economics, restrictive seed laws are accelerating the erosion of Indigenous knowledge and cultural practices. June Bartuin explained that women were traditionally the custodians of seeds, preserving them using low-cost methods such as smoke storage in traditional houses.

“This maize could be stored for two, three, even five years, and when planted, it germinated very well,” she added.

The collaboration between Witness Radio and the Seed Savers Network brings together grassroots organizing and community media to amplify farmers’ voices. The Seed Savers Network, a grassroots organization based in Kenya, works with more than 500,000 farmers and supports 121 community seed banks across the country.

According to Mercy Ambani, Resource Mobilization Officer at Seed Savers Network, the organization focuses on rebuilding farmers’ confidence, knowledge, and rights, making platforms such as Witness Radio ideal for reaching farmers directly.

“Our vision is to protect seed sovereignty, conserve biodiversity, and strengthen farmers’ rights through policy advocacy and practical action,” she said.

Through initiatives such as the Seed School, farmers, researchers, and activists are trained in seed selection, storage, preservation, and community seed bank management.

“In December 2024, Kenyan farmers achieved a landmark court ruling that struck down parts of the Seed and Plant Varieties Act, showing the power of collective action and legal advocacy to protect farmers’ rights.”

“This ruling showed that there is power in numbers,” said Ambani. “When farmers raise their voices together, change is possible.”

Regional knowledge exchange is also growing. Farmers from Uganda and Ghana who attended the Seed Savers Boot Camp have returned to their communities to establish household seed banks, kitchen gardens, and farmer field schools.

“My home has become a farmer’s field school. People are hungry for this knowledge,” said Nakato.

Without reforms that recognize and protect farmer-managed seed systems, farmers risk losing control over their seeds — and with them, control over food, culture, and livelihoods.

“If we lose our seeds, we lose our culture, our food, and our future,” Bartuin emphasized.

Wokulira Geoffrey Ssebaggala, Team Leader at Witness Radio, highlighted the importance of creating space for farmers to share knowledge and experiences.

“We are providing a platform where farmers and experts can exchange knowledge on sustainable farming practices. We believe this radio content will have a real impact on food and seed sovereignty across Africa.” Mr. Ssebaggala added.

The radio series will continue to provide practical knowledge, farmer voices, and policy analysis to support sustainable agriculture across Africa.

Related posts:

Happening shortly! Kenya’s upcoming court ruling on the Seed Law could have a significant impact on farmers’ rights, food sovereignty, and the country’s food system.

Happening shortly! Kenya’s upcoming court ruling on the Seed Law could have a significant impact on farmers’ rights, food sovereignty, and the country’s food system.

Seed Sovereignty: Most existing and emerging laws and policies on seeds are endangering seed saving and conservation on the African continent.

Seed Sovereignty: Most existing and emerging laws and policies on seeds are endangering seed saving and conservation on the African continent.

The EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025, is a potential threat to smallholder farmers, as it aims to disengage them from the agriculture business, according to experts.

The EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025, is a potential threat to smallholder farmers, as it aims to disengage them from the agriculture business, according to experts.

Seed Boot Camp: A struggle to conserve local and indigenous seeds from extinction.

Seed Boot Camp: A struggle to conserve local and indigenous seeds from extinction.

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Close to six years on, Pangero Chiefdom subjects still linger in pain after the government army’s forceful takeover of their ancestral land.

Published

1 day agoon

February 3, 2026

By Witness Radio Team

It was a bolt from the blue—an unimaginable shock that arrived without warning. Close to six years on, its consequences have hardened into everyday reality, and justice remains elusive. That shock was felt most acutely in Pangero Chiefdom, where a once-stable community is still grappling with the aftermath of an abrupt and forceful military land takeover, highlighting ongoing land injustice.

The Pangero Chiefdom of the Alur Kingdom is located in Koch Parish, Nebbi Sub-County, Nebbi District, in north-western Uganda, north of Lake Albert and near the Uganda–DR Congo border. For decades, families here depended on the land for farming, food, and cultural continuity, with traditions and livelihoods deeply tied to the soil.

The wounds from the land loss remain raw, and the community continues to demand the return of their land and justice for their suffering.

Over 100 families across Aleikra, Kochi Central, and Panyabongo villages have been directly impacted by the land grab, according to the Traditional Chief.

In Uganda, land is often taken from people with low incomes through a system lacking explicit legal protections, raising questions about the legitimacy and fairness of land seizures, especially when communities are evicted without free, prior, and informed consent.

“When forces such as the Army occupy community land, people are always afraid even to ask why they are settling or why they have settled on their land. It becomes difficult to question men in uniform,” said Mr. Ulama Dison Duke Ukerson, the Traditional Chief of Pangero Chiefdom, in an interview with Witness Radio Uganda.

In March 2020, hell broke loose in the chiefdom as residents woke up to find UPDF soldiers camping on their land. Many initially thought the soldiers were temporarily stopping over on their way elsewhere. However, after some time, it became clear that the force was not moving on but instead settling in the lush environment of Pangero.

When confronted, residents claim the soldiers explained that they were taking refuge, with Zombo District as their ultimate destination.

“They have stayed there for now, close to six years. Initially, they told us they would take refuge for a few days and later move to the Zombo District. Some left, but others remained. We initially thought they were staying for a few weeks. Since then, they have stayed on our land without paying anything,” said Gladys Budongo, an elder in the chiefdom, in an interview with Witness Radio.

Forty-one-year-old Doreen Kawambe, a resident of Aleikra Village, is among those who lost part of their land during the takeover. Doreen said she originally owned seven acres inherited from her father.

“When the UPDF came, they seized three acres of our land. The remaining land is difficult to access. My family was left with only four acres. We can no longer go to the forest for water, and the areas we used to cultivate are now guarded. Food has become a serious problem,” she said.

Before the takeover, Doreen’s land provided enough income to sustain her family. “From one acre, I could earn up to 800,000 shillings (about 224.94 USD) or more in a season. Now, with less land and limited access, survival is tough.” She explained.

Gladys Budongo, a 61-year-old widow, also lost her late husband’s five-acre family land, which is part of a larger ancestral estate that the family has occupied for decades.

Amid community resistance and ongoing efforts to reclaim their land, the Army conducted surveys and valuations in 2023 and 2024. However, elders like Gladys Budongo claim the process was irregular and imposed without community consent, highlighting the need for legal accountability.

“Koch Land Committee also pressured the community to accept the survey exercise. Although it was supposed to represent the local population, it was not democratically elected by consensus, as is traditional in Alur communities, and instead consisted of an imposed elite who pressured us to surrender our land,” she said.

According to elders interviewed by Witness Radio, during an announcement meeting on September 19, 2025, facilitated by officials from the UPDF Land Board, the national surveyor, and the Commander of Koch Army Barracks, community members were compelled to sign documents accepting meager compensation for land seized five years earlier.

“Residents whose land was surveyed were given two choices: either sell their land to the Army by accepting the compensation offered or refuse the UPDF’s offer,” the area chief said, adding that officials barred him from speaking or defending his chiefdom.

“Leaders in the area are rough when we oppose this land grab. Even in meetings, they don’t allow me to speak. On the few occasions I attended and got silenced,” he said.

Mr. Opio Okech, a community land defender, blamed the government and the Army for forcefully occupying people’s land.

“The forced decision to sell land to the government is similar to eviction because people have no say. The problem started when the government entered the land, stayed for a long time without proper notice, and then decided it would not leave and instead offered compensation. It looks, smells, and walks like a forceful eviction,” he said.

Despite promises of compensation, Gladys and others say they have not received any payment.

“They forced people to sign documents, but nobody has been paid yet. Some were threatened with arrest if they protested,” she said.

Koch Resident District Commissioner (RDC) Mr. Abak Robert, representing the Office of the President, denies allegations of land grabbing, stating the land was acquired on a willing buyer, willing seller basis, which raises questions about the transparency and legality of the process.

“I personally participated in monitoring the project-affected persons. People who accepted giving land to the UPDF were properly valued, accepted the figures, and signed willingly,” he said in an interview with Witness Radio.

When asked how this arrangement worked, given that compensation was considered only after the land had already been forcibly taken, he responded that the government would soon pay the affected people.

“Compensation is expected soon, and the community is agreeable to receiving monetary payment,” the RDC added, noting that the land currently occupied by the UPDF in Pangero Chiefdom spans more than 242.811 hectares.” He added.

However, affected residents insist that the survey and valuation process involved intimidation and coercion.

Capt. David Kamya, the 4th Division Public Information Officer based in Gulu District, declined to comment about the UPDF’s improper land acquisition upon being contacted by Witness Radio.

“How sure are you that the UPDF grabbed the land? I was told that if someone wants to talk about such matters, they must be on the ground. Come, and we meet and see this physically,” he said before hanging up.

The consequences of the land seizure extend beyond economics. According to the chiefdom elders, families struggle to sustain livelihoods, children go hungry, and elders feel powerless in the face of military authority.

“People are afraid to speak out. We are threatened when we ask for justice. It feels like the community has no voice. The loss of ancestral land is also cultural. Trees, rivers, and open spaces that connected generations have been taken over, disrupting a way of life that has lasted centuries,” she added.

Nearly six years after the UPDF’s arrival, the Pangero Kingdom remains a community in limbo.

“We want someone to stand for us to stop them from taking our land or even buying it as they promise. They refuse to hear the elders’ voices and do whatever they want. We want our land back,” said the traditional chief, whose houses now accommodate soldiers.

Related posts:

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Uganda’s plan to allow forceful takeover of private land stirs anger

Uganda’s plan to allow forceful takeover of private land stirs anger

Ugandan army to punish soldiers for torturing Journalist in Kampala

Ugandan army to punish soldiers for torturing Journalist in Kampala

Nine (9) years and still counting: Buvuma residents still await compensation for land grabbed by the Oil palm project.

Nine (9) years and still counting: Buvuma residents still await compensation for land grabbed by the Oil palm project.

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Indigenous communities in Eastern Nepal accuse the World Bank’s Linked Cable Car Project of rights violations.

Published

3 days agoon

February 2, 2026

Indigenous communities in Eastern Nepal accuse the World Bank’s Linked Cable Car Project of rights violations.

By Witness Radio Team

A $22 million cable car project cutting through sacred forests in eastern Nepal has become the centre of a growing dispute. Indigenous communities accuse developers and the World Bank Group of enabling forced development that violates community land rights and exacerbates human rights abuses.

The project, whose construction began in 2022, is developed by Pathibhara Devi Darshan Cable Car Pvt. Ltd., a subsidiary of Nepal’s powerful IME Group, and is being built on Mukkumlung Mountain, also known as Pathibhara, in Taplejung District. While the government has promoted the project as a tourism and accessibility initiative, the Indigenous Yakthung (Limbu) communities say construction has proceeded without their consent and at a high cultural and environmental cost.

According to the project’s Initial Environmental Examination (IEE), the cable car infrastructure would occupy 6.22 hectares (15.36 acres) of community and government forest land.

Community leaders opposing the project say it threatens local livelihoods and social structures, including more than 700 local porters, nearly 30 locally run small businesses, and approximately 1,700 households that depend on pilgrimage-related income. They also warn of irreversible damage to cultural heritage sites.

The cable car intends to transport pilgrims to the Pathibhara Devi temple, one of Nepal’s most revered Hindu shrines, which is currently accessible only via a steep, high-altitude trek. Project developers argue the cable car will boost tourism, generate employment, and allow elderly and disabled devotees easier access.

For the Yakthung people, Mukkumlung is not merely a pilgrimage site but a sacred ancestral land that embodies their spirituality, culture, and identity.

“This mountain is sacred ancestral land. It defines our spirituality, culture, and customary law,” said Advocate Shankar Limbu, vice-chair of the Lawyers’ Association for Human Rights of Nepalese Indigenous Peoples (LAHURNIP). “Clearing forests and altering the mountain’s ecology weakens its spiritual power and violates our collective rights.”

Local leaders say they were never consulted before construction began, highlighting a clear violation of their rights and raising concerns over FPIC breaches.

“The IFC’s own Performance Standards state that Indigenous Peoples have the right to give Free, Prior and Informed Consent to projects on their lands,” said Saru Singak of the Mukkumlung Conservation Joint Struggle Committee. “But no one ever asked us whether we wanted this project. It is destroying forests and sacred landscapes and disrespecting our religion and culture.”

Environmental groups report that construction has already felled over 10,000 trees, including

protected species like Himalayan yew, threatening local biodiversity.

As forest clearing accelerated, opposition from local communities intensified. In January 2025, Nepal Police and Armed Police Force personnel reportedly used force against protesters, leading to the detention of dozens and sustaining severe injuries. Activists allege continued intimidation and retaliation against those opposing the project.

The dispute has drawn international attention, especially as the World Bank Group faces mounting scrutiny over financing harmful investments. Between August 2022 and July 2024, the IFC provided advisory services to the IME Group for four cable car projects in Nepal, including the Pathibhara project.

Indigenous leaders argue that during this period, the IFC failed to ensure compliance with its Environmental and Social Performance Standards, particularly regarding environmental assessments and the respect for communities’ right to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent, raising questions about its oversight and accountability.

In August 2025, Yakthung communities, supported by lawyers and civil society organisations, filed a formal complaint against the World Bank Group, alleging breaches of safeguarding standards that led to human rights abuses and the destruction of cultural heritage. In December 2025, the World Bank Group’s independent watchdog, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO), formally registered the complaint and is currently assessing whether to proceed with mediation or a full compliance investigation.

For Indigenous rights advocates, the Pathibhara dispute reflects a broader pattern seen in World Bank–linked projects across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where development initiatives proceed without meaningful community participation and accountability mechanisms are activated only after harm occurs, yet rarely provide a remedy.

A decade ago, an 11-month investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), Evicted and Abandoned, found that an estimated 3.4 million people were physically or economically displaced by World Bank–funded projects, raising long-standing concerns over the institution’s ability to protect vulnerable communities.

IME Group operates across energy, manufacturing, infrastructure, and trade, and owns Global IME Bank, Nepal’s largest commercial bank. The IFC has provided more than $50 million to IME Group over the past decade.

Related posts:

Thirty-six (36) groups from all over the world have written to industrial agriculture investors, Agilis Partners Limited to stop human rights violations/abuses against thousands of indigenous/local communities, settle grievances, and return the grabbed land.

Thirty-six (36) groups from all over the world have written to industrial agriculture investors, Agilis Partners Limited to stop human rights violations/abuses against thousands of indigenous/local communities, settle grievances, and return the grabbed land.

A German Bank is under intense scrutiny for its irresponsible banking practices, which have been directly linked to displacement and human rights abuses.

A German Bank is under intense scrutiny for its irresponsible banking practices, which have been directly linked to displacement and human rights abuses.

Know Your Land rights and environmental protection laws: a case of a refreshed radio program transferring legal knowledge to local and indigenous communities to protect their land and the environment at Witness Radio.

Know Your Land rights and environmental protection laws: a case of a refreshed radio program transferring legal knowledge to local and indigenous communities to protect their land and the environment at Witness Radio.

Profiting from misery: A case of a multimillion-dollar tree project sold off before resolving land grab and human rights violation claims with local communities.

Profiting from misery: A case of a multimillion-dollar tree project sold off before resolving land grab and human rights violation claims with local communities.

The Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network Joint Radio program boosts Farmers’ knowledge of seed and food sovereignty.

Close to six years on, Pangero Chiefdom subjects still linger in pain after the government army’s forceful takeover of their ancestral land.

Indigenous communities in Eastern Nepal accuse the World Bank’s Linked Cable Car Project of rights violations.

Why govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Swedish pension fund drops TotalEnergies amid rising EACOP risks

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoWomen environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoUganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

-

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoEvicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoWitness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoWhy govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days agoIndigenous communities in Eastern Nepal accuse the World Bank’s Linked Cable Car Project of rights violations.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day agoClose to six years on, Pangero Chiefdom subjects still linger in pain after the government army’s forceful takeover of their ancestral land.