The African Union is putting the finishing touches to the

draft protocol on intellectual property rights to the agreement establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Once ratified, this text will form an integral part of the AfCFTA and will be applied across all 54-member countries. The protocol will apply to all categories of intellectual property, including plant varieties, genetic resources and traditional knowledge. Specifically, it will aim to promote “coherent” intellectual property rights policy and a harmonised system of intellectual property protection throughout the continent (article 2.2.).

Given that intellectual property rights privatise agricultural biodiversity – our collective heritage and the cornerstone of food sovereignty – the implications of this protocol on seeds and the rights of peasants and rural communities in Africa must be carefully analysed.

Around the world, free trade agreements are

forcing the privatisation of seeds, whether through patents or plant breeders’ rights. These rights enable seed companies to demand royalty payments from farmers for each generation of seeds they use, over a period of 20 to 25 years. According to seed companies such as Syngenta and Bayer, without these payments they will be unable to invest in research.

This same system is now rapidly gaining ground in Africa, potentially upsetting relationships between citizens within members states, and even between the member states themselves.

Article 8 of the draft protocol addresses this issue. It stipulates that state parties shall provide protection for new plant varieties through a legal system that includes farmers’ rights, plant breeders’ rights, and rules on access and benefit sharing “as appropriate”.

Furthermore, it adds that states shall comply with “additional obligations” set out in an annex to be developed once the protocol is adopted. Upon adoption, this annex, along with the annexes on traditional knowledge and genetic resources, will have the same legal value as the protocol (article 41 of the protocol).

Our analysis of these provisions seeks to address the following questions: What does this protocol mean for African countries? How will they implement it? What impact will it have on farmers and food sovereignty in Africa?

The meaning of the protocol

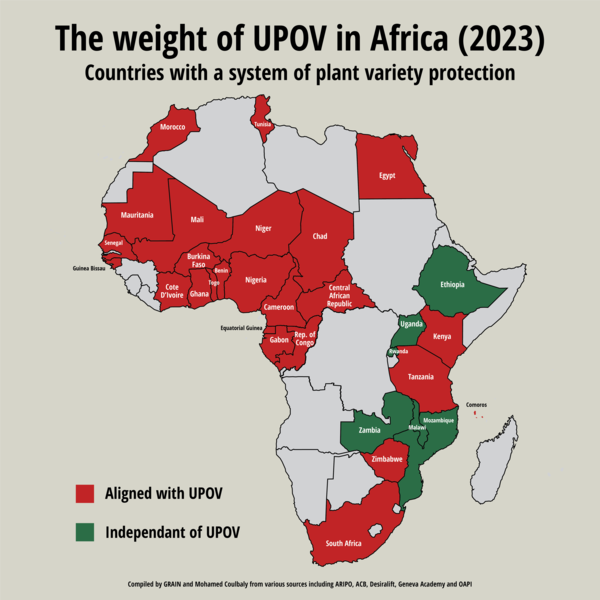

Spurred on by the World Trade Organisation (WTO), and under pressure from other bodies, half of all African countries have already introduced an intellectual property rights system on seeds. The vast majority follow the model of the 1991 convention of the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV). (See graph.)

This system is highly criticised for promoting genetic uniformity of crops and preventing peasants from reusing seeds. The question now is whether the AfCFTA protocol will challenge this dominant system. The final draft text suggests that the answer is ‘no’.

Despite progressive-sounding references to farmers’ rights and benefit sharing, the protocol sets out the same requirements as the WTO, i.e., states must set up a plant variety protection system. Given that half the African countries already adhere to the UPOV model, it is highly likely that the AfCFTA protocol will simply reinforce, or even accelerate, this trend.

The protocol’s approach, consisting of requiring both the protection of breeders’ rights and farmers’ rights, as well as rules on access to genetic resources, is a ploy in the sense that the use of “as appropriate” strips it of all relevance. Presented in this way, the provision becomes more of a guideline, with member states left to apply this article in their own territories as they see fit.

Naturally, it will be implemented in line with their existing obligations, whether these stem from the WTO, the African Intellectual Property Organisation (OAPI) or the African Regional Intellectual Property Organisation (ARIPO). This “fait accompli”, with half the states already bound to UPOV to varying degrees, makes it difficult, or even impossible, to deviate from the status quo.

UPOV in conflict with all other agreements

As UPOV does not recognise farmers’ rights, whether derived from the

International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture or the

UN Declaration, it enters into direct conflict with these agreements. UPOV

refuses to include rules on access to resources and benefit sharing, as set out in the Convention on Biological Diversity or, once again, the FAO Treaty. Since they are not “suitable” for UPOV, these additional elements will not materialise.

The conflict goes further still. In articles 18 and 20, the AfCFTA protocol requires states to oblige breeders to respect three conditions before they are granted a right to a new variety. These three conditions are: (i) to state the source of traditional knowledge or resources utilised in developing the new variety, (ii) to provide proof of free, prior and informed consent from the competent authorities under the relevant national regime, and (iii) to demonstrate proof of fair and equitable benefit sharing arising from the use of such resources or knowledge under the relevant national regime.

[1] Yet these conditions do not correspond to UPOV rules, so what is the likely outcome?

It is highly likely that the African countries that conform with UPOV will continue to do so, even if

they hardly

benefit from it

. It may be the case that those who wish to go further will do so, by applying additional conditions. However, we cannot see how governments will change the conditions for granting plant variety rights in UPOV member countries. In these countries, there is a risk that the protocol’s provisions will go unheeded.

It is hard to see how the draft protocol could achieve its objective of promoting coherence and harmonising intellectual property rules and principles in Africa if all AfCFTA member countries are given free rein to implement the protocol’s requirements as they see fit. Perhaps the annexes, which are still being negotiated, will shed light on this.

Conflicting farming models

The draft protocol to the AfCFTA agreement comes at a crucial time for Africa. The continent is divided in two on how it views the future of agriculture in Africa and the role of farmers. Some advocate and adhere to the idea of agribusiness taking a lead, with or without the involvement of small farmers. Others are seeking to strengthen family, peasant and autonomous farming and agroecology. These two rather opposing approaches are based on completely different seed systems and discussions about rights.

Across a number of countries, the industrial system promoted by UPOV is coming under fire. This can be seen in

Benin, where farmers’ organisations are taking a stand against the government’s proposal to join UPOV. This is also evident in

Kenya and

Ghana, where legal proceedings are underway to amend or declare unconstitutional UPOV-based plant variety laws. Furthermore, in

Southern Africa, a campaign to block alignment with UPOV, precisely because of the threats it poses to family farming in the sub-region, is slowing down progress on the ARIPO project. It can be seen in

Tunisia and

Mali, where civil society organisations are promoting a completely different approach to seed laws, based on the demands and criteria of the farming communities themselves. Lastly, it is apparent from the many

initiatives and

caravans run by local communities in alliance with others, lobbying local authorities and raising public awareness to call for an end to UPOV in favour of fundamental respect for farmers’ rights.

This conflict between production models and rights systems is reflected in the field of animal farming. The government of Burkina Faso

was recently granted an exclusive right to the term “poulet bicyclette” (“bicycle chicken”, a common term for native chicken). It is a registered trademark and applies to live chickens, chicken meat and veterinary products for chickens. This exclusive right is effective in all 17-member countries of OAPI for a period of 10 years. However, the term “bicycle chicken” has been used

across Western and Central Africa for a very long time to refer to local breeds, peasant breeds. It represents a collective heritage and is central to many agroecology projects. Benin has now banned the sale of frozen chickens, known as “morgue chickens”, across its territory in order to promote the farming of native chicken breeds, i.e., “their” bicycle chickens. Will the government of Burkina Faso exercise its veto or monopoly rights against this policy? Even the AfCFTA protocol supports this approach.

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day ago