Patrick Pouyanné of Total; Tanzania’s President Samia Suluhu Hassan, and President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda after signing agreements for the controversial pipeline. Photograph: Courtesy of Total – Uganda

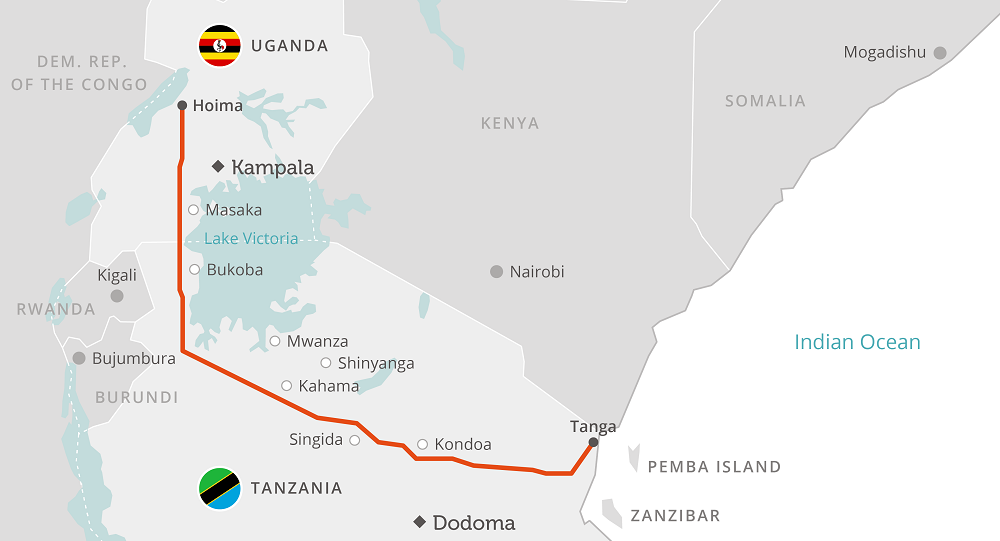

Activists say the ‘heart of Africa’ line shipping crude from Uganda to Tanzania is unnecessary and poses a huge environmental risk

Activists have accused French and Chinese oil firms of ignoring huge environmental risks after the signing of accords on the controversial construction of a £2.5bn oil pipeline.

Uganda, Tanzania and the oil companies Total and CNOOC signed three key agreements on Sunday that pave the way for construction to start on the planned east African crude oil pipeline (EACOP). But on Tuesday a letter signed by 38 civil society organisations across both east African countries said the parties had failed to address environmental concerns over the pipeline and had steamrollered over court and parliamentary processes.

Work is expected to begin this year on what would be the world’s longest electrically heated pipeline, which will move crude oil from fields near Lake Albert in western Uganda 900 miles to Tanzania’s Indian Ocean seaport of Tanga. Uganda’s crude oil is highly viscous, so it must be heated to be kept liquid enough to flow.

Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, and his Tanzanian counterpart, Samia Suluhu Hassan, witnessed the signing of agreements between shareholders, host governments, and on tariff and transport between EACOP and the Lake Albert oil shippers.

Uganda discovered reserves of crude near Lake Albert on its border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in 2006, and the landlocked country wants a pipeline to transport oil to international markets.

“These agreements open the way for the commencement of the Lake Albert development project,” Total said in a statement on Monday. “The main engineering, procurement and construction contracts will be awarded shortly, and construction will start. First oil export is planned in early 2025.”

The oil will come from two projects – the Tilenga project, operated by Total, and the Kingfisher project, operated by CNOOC, which together are expected to produce up to 230,000 barrels a day. Government geologists estimate total reserves at 6bn barrels.

However, Diana Nabiruma, of the Africa Institute for Energy Governance (AFIEGO), told the Guardian: “It is concerning that major agreements are being signed and the companies are being given the go-ahead to award contracts and start developing the Lake Albert oil project.

“The oil projects pose major environmental risks. Resources, some shared with countries such as the DRC, Tanzania and Kenya, including Lake Albert as well as Lake Victoria and rivers, are at risk of oil pollution,” she said

A globe at Uganda’s Murchison Falls national park. Activists fear the 900-mile pipeline poses risks to water resources and fisheries. Photograph: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP/Getty

“The resources support the fisheries, tourism and other economic activities. They are also important for food and water security. They therefore must be conserved.”

The #StopEACOP alliance campaign condemned the decision to build the pipeline, which it says will displace 12,000 families and would be a huge environmental risk at a time of climate emergency, when the world needs to move away from fossil fuels.

Vanessa Nakate, founder of the Rise Up climate movement in Uganda, said: “There is no reason for Total to engage in oil exploration and the construction of the east Africa crude oil pipeline because this means fuelling the destruction of the planet and worsening the already existing climate disasters in the most affected areas.

“There is no future in the fossil fuel industry and we cannot drink oil. We demand Total to rise up for the people and the planet,” she said.

Lucie Pinson, of Reclaim Finance, which works to decarbonise the financial system, added: “We call on banks to publicly commit to stay clear of the project and investors to vote against Total’s climate strategy and the renewal of the mandate of its CEO Patrick Pouyanné at the group’s AGM in May.”

Last week, more than 260 African and international organisations sent an open letter to 25 commercial banks urging them not to finance the construction of the EACOP.

David Pred, of Inclusive Development International, which supports communities to defend their rights against harmful corporate projects, said: “The oil companies are trying to dress up the investment decision signing ceremony, but fortunately this climate-destroying project is far from a done deal.

The country has yet to see anything of the oil bonanza that seemed near when deposits of crude were discovered in 2006. Photograph: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP/Getty

“Total is also taking into the highest consideration the sensitive environmental context and social stakes of these onshore projects. Our commitment is to implement these projects in an exemplary and fully transparent manner.”

CNOOC has been approached for comment.

But Nabiruma accused the two east African governments of racing to sign deals before their citizens had been told how any risks would be “avoided, minimised or mitigated”.

Robert Kasande, permanent secretary at Uganda’s ministry of energy and mineral development, said: “We are very mindful of the environment that we work in. It’s a very sensitive ecosystem. So we have put everything that we need to do in place.”

He said the project was being conducted in accordance with the Equator principles – a risk-management framework adopted by financial institutions for assessing and managing environmental and social risk in projects.

“This is a big project for us as a country,” Kasande said. “These resources that are going to be coming into the country are going to be a huge boost to this economy.”

Original Source: The Guardian.com

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago