In light of the growing number of cold and hot wars around the world, attention to climate issues has noticeably declined, at least in Germany. Meanwhile, supposed solutions, such as carbon emission trading and the Clean Development Mechanism, continue to be promoted. As Maria Neuhauss argues, this is a bluff with far-reaching consequences.

There was more bad news in January 2025: The European Earth observation program Copernicus and the World Meteorological Organization reported that the global average temperature in 2024 was 1.6 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. This marked the first time the average global temperature exceeded the 1.5-degree target established in the Paris Climate Agreement.

In light of the growing number of crises and conflict hotspots around the world, attention to climate issues has noticeably declined, at least in Germany. While 1.4 million people demonstrated for more climate protection in Germany in September 2019, according to Fridays for Future, it is now almost impossible to speak of a climate movement. The catalyst for the third German ‘movement cycle’ was undoubtedly the rebranding of Last Generation in December 2024. The group had been decimated by state repression and media agitation in the preceding months. The U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement at the beginning of this year made it clear that defenders of the fossil fuel status quo have gained momentum and intend to achieve their goals without compromise. However, as global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise and the material world follows its own rules, the problem of global warming will likely resurface in the collective consciousness in the foreseeable future. Whether through heat waves, extreme weather events, water shortages, or forest fires. The question is whether and what new answers and approaches a reinvigorated climate movement will develop if it does not limit itself to ‘solidarity prepping’ and actually wants to influence the course of events.

Central to this is not only resolute resistance against fossil inertia forces, but also testing the actions of liberal actors. Although they acknowledge the problem of climate change and claim to want to solve it, the measures they take are inadequate at best or, at worst, create new profit opportunities for the industries that must be phased out. This is far from a comprehensive solution to the ecological crisis, which encompasses more than just climate change. Emission trading and the associated offset mechanisms that are part of the international climate negotiations are one example that illustrates this well.

‘Climate math’ of flexible mechanisms

Emission trading is based on the idea that greenhouse gas emissions are still possible but must be justified with corresponding ‘pollution rights.’ The number of certificates is limited and should decrease over time to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Emission trading provides fundamental flexibility by allowing certificates to be bought and sold. Ultimately, this is intended to achieve the most cost-efficient climate protection possible because emission-reducing measures are expected to be implemented first where they can be done quickly and cheaply. This allows one to profit from selling unused emission allowances to other actors who initially shy away from such measures. These actors must buy the allowances until the increased prices resulting from the shortage make emission-reducing measures unavoidable. At least, that’s the theory.

Emission trading is closely linked to the concept of climate neutrality, which plays a central role in climate policy. Greenhouse gas emissions are offset by preventing emissions, using natural carbon sinks, or removing CO2 from the atmosphere. The trick to this ‘climate math’ is that, as long as emissions are compensated for, they do not count, even if greenhouse gases continue to be released into the air. These compensation measures are called ‘offsets.’

The idea that not all emissions must be reduced but can, in principle, be bought out of this obligation is based on the global inequalities that have developed historically and that fundamentally structured the first global climate agreement, the Kyoto Protocol of 1997. In line with the ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ approach, the protocol only required industrialized countries to reduce emissions because they were mainly responsible for the high concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. However, under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), industrialized countries could partially buy their way out of this responsibility by financing emissions-reduction measures in developing and emerging countries. The CDM has therefore been described as a modern “indulgence trade” (Altvater & Brunnengräber, 2008). This allowed industrialized countries to reconcile their energy production methods with the need for climate protection while outsourcing conflicts over the energy transition, such as land use, to the Global South (Bauriedl, 2016).

Social and environmental shortcomings of the CDM

From a climate protection perspective, however, it only makes sense to include emission reductions in developing and emerging countries in the emissions balance of industrialized countries if the investments actually help reduce emissions – that is, if the projects would not have been realized without investments from the Global North. Conversely, if projects under the CDM are not additional, such as if a dam would have been built without investments from the Global North, companies in industrialized countries can claim emission credits without actually helping to reduce emissions. This is because the emissions would have been avoided anyway. This would result in an overall increase in emissions.

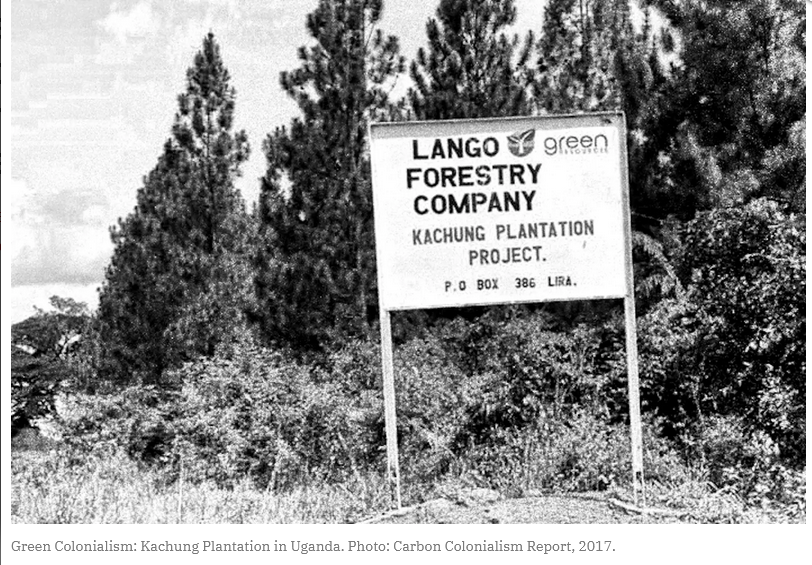

In fact, the additionality of many projects financed under the CDM has been questioned over the years (Öko-Institut, 2016). However, less attention has been paid to the fact that CDM projects have repeatedly led to the displacement of local people and land grabbing. For example, a reforestation project in the Kachung Central Forest Reserve in Uganda displaced many neighboring villagers who used to farm and graze their cattle there. Plagued by food insecurity, hunger, and poverty, the population was denied access to the land when CDM-approved plantations were established, further worsening their situation. The monoculture plantations also had negative ecological consequences (Carbon Market Watch, 2018). Thus, the CDM perpetuated colonial conditions on several levels. The mechanism ended with the expiration of the Kyoto Protocol in 2020. However, credits issued beforehand can still be used under the Paris Climate Agreement.

Price incentives instead of bans

A critical review of emission trading is also urgently needed. It is failing as a suitable means of climate protection on several levels. For example, in the case of the European Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), the continued generous allocation of free certificates, particularly to energy-intensive industries, protects those responsible for high CO₂ emissions from strict requirements. Additionally, the emission trading approach suffers from the fact that it is unclear whether, or to what extent, the price of emissions certificates influences investment decisions in favor of climate protection. According to various studies, the price would need to be between EUR 140 and 6,000 per ton of CO₂ to achieve the 1.5-degree target (IPCC, 2018).

However, local industry is already complaining about excessively high electricity prices (the average certificate price in 2024 was €65 per ton of CO₂), causing the government to worry about the location’s attractiveness. Given this, can we really expect politicians to force energy-intensive industries to do more to protect the climate with much higher certificate prices? Ultimately, this reveals a fundamental flaw in emission trading: its indirect effect. Instead of using targets and bans, the idea is to persuade companies to cut emissions through price incentives. However, this approach puts climate protection in the hands of actors who primarily follow the profit motive and do not necessarily translate the price signal into climate protection measures. This explains why companies enrich themselves from emission trading and the Clean Development Mechanism wherever possible (CE Delft, 2021).

For those who design and control emission trading systems, the aforementioned criticisms are merely one reason to continue supporting and refining the chosen method. This is also true for the EU, which, after a period during which emission trading was considered ineffective due to low prices, reinvigorated the system at the end of the 2010s. For instance, the EU introduced the market stability reserve. The goal is to maintain public confidence in the effectiveness of this instrument because it is the global climate protection tool. However, evaluations of its effectiveness are rare and provide little cause for optimism. According to an evaluation of various studies, the EU ETS achieves only 0 to 1.5% emission reductions per year (Green, 2021).

History and responsibility are being erased

This makes the ongoing negotiations at UN climate conferences concerning the implementation of global emission trading and a new Clean Development Mechanism all the more critical. In addition to the question of how financially weak countries will be compensated for climate-related damage and losses, the annual COPs primarily address Article 6 of the Paris Climate Agreement. Article 6 regulates international cooperation, i.e., the extent to which a country can count mitigation measures or emission avoidance elsewhere in its climate balance. Last year’s COP29 in Baku further advanced the operationalization of this article. Based on this, old CDM projects can now be transferred to the new Sustainable Development Mechanism under certain conditions. However, the first project to clear this hurdle reportedly reported emission reductions up to 26 times higher than expected based on scientific evaluation (Mulder, 2025).

Despite urgent warnings, world climate conferences seem determined to repeat past mistakes. The focus is on profit. As Tamra Gilbertson summed up in an interview with Chris Lang, the climate is the last priority. After all, trade processes will incur deductions in the future that will flow into the international adaptation fund. However, according to Gilbertson, this is also due to the fact that the climate conferences have failed to reach viable agreements on financing climate damage and adaptation measures in poorer countries thus far. Instead, emission trading is expected to deliver the necessary funds. “This is where common but differentiated responsibilities are eradicated. History and responsibility are erased, and capitalism in the form of carbon markets takes its place” (Lang, 2024).

While these processes are difficult for the public to understand, the escalating climate crisis requires critical attention more than ever. The problems associated with emission trading and the Clean Development Mechanism urgently need to be exposed as distractions from the real task at hand: rapidly phasing out fossil fuels.