SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

They should not be called public development banks

Published

5 years agoon

From 9-12 November 2020, 450 finance institutions from around the world will gather for the first international meeting of public development banks, dubbed the “Finance in Common” summit, hosted by the French government. The institutions, which range from the World Bank to the China Development Bank, collectively spend $2 trillion a year on so-called development projects – roads, power plants, agribusiness plantations and more. Much of this spending is financed by the public – us – which is why they called themselves “public development banks”. But our partners on the ground and our experience teach us they are not public and what they fund is not development.

For the most part, these institutions get their money from public coffers, fuelled by people’s labour and taxes. As state-owned institutions, they have the obligation to respect and protect human rights in their policies and operations. And they are supposed to be accountable to the public, through government oversight bodies. But that accountability hardly exists. From Proparco in France, to BIO in Belgium, to DFC in the US, few people have heard of these development banks much less know what they are up to.

In contrast to development cooperation bodies, which provide grants and loans to governments of the global south, development banks invest in the private sector for a financial return. They argue that companies drive growth and jobs, and, for this to happen, financiers have to take risk, for example through debt and private equity. A few million dollars from a development bank gives companies a form of guarantee that they can then use to raise more millions from private lenders or other development banks, often at a cheaper rate. This is how the development banks play such a critical role in enabling corporations operating in the global south to expand further into markets and territories – from polluting coal plants in Bangladesh, to controversial hydroelectric dams in Honduras, to hazardous soybean plantations in Paraguay – in ways they could not otherwise.

As civil society organisations working closely with partners and communities in the global south, we are most familiar with these institutions’ involvement in agriculture. What they contribute to can hardly be called development. We have witnessed how they invest primarily in agribusiness companies and an industrial model of agriculture that is a main driver of both pandemics and the climate crisis. Development banks have little track record for supporting locally-controlled food systems or peasant-led agroecological farming, which are the real solutions to these two problems.

Over the past five years, for instance, a number of groups have worked together to support communities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo badly affected by a Canadian oil palm plantation company that received more than $140 million in financing from numerous development banks, including approximately $88 million from the UK development bank CDC Group. The company, Feronia Inc, was majority-owned by the development banks until it went bankrupt this year and was handed over to a private equity fund based in the tax haven of Mauritius. Feronia, which never made a profit but paid its expat staff handsomely, would have collapsed years ago had it not been for the intervention of the development banks.

It was argued that the involvement of these institutions would provide leverage for the local communities living in and around the plantations to address their long-standing grievances that have existed ever since the lands were stolen from them at gunpoint over a 100 years ago by the then Anglo-Dutch giant Unilever and colonial Belgium’s King Leopold. They have suffered immensely over the past century, and any sincere commitment to “development” could only be possible if it began by addressing the theft of their lands and forests and led to land restitution and reparations. But the development banks have resisted any meaningful movement down this path. In fact, it’s been quite the opposite.

They have taken no action to address the historic conflicts over the nearly 100,000 hectares of land concessions or the allegations of corruption plaguing the project. Their environmental, social and governance (ESG) plans did nothing to alleviate poverty in the communities. And the involvement of the various banks did not reduce rampant human rights violations against villagers or workers. What’s worse, the banks have acted to undermine the community efforts to use the grievance mechanisms that they themselves established.

The reality is that no matter the ESG guidelines or codes of conduct against land grabbing, there is no way that development bank investments in industrial plantations can contribute to “sustainable development”. These plantations are colonial relics, designed purely to extract profits for their owners and to produce commodities for foreign buyers. They require stolen lands, exploited labour and armed violence to keep distraught villagers and workers from rising up. The creation of “jobs” and social projects, like poorly equipped schools and health clinics, that the development banks use to justify their presence is merely the theft and destruction of lands and resources that the villagers once had to sustain themselves.

Let us be clear: public development banks are disconnected from any sense of what “public” means and any argument about what “development” should look like. In food and farming, the backbone of our very existence, they finance corporate agribusiness. They were not set up to support any other model and have no real capacity to do so. As industrial agriculture is responsible for up to 37% of the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions, the case to dismiss development banks is clear. We need a very different approach to international finance that supports communities rather than companies, and food systems free of corporate control.

Signed by

Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa – Africa

WoMin African Alliance – Africa

Entraide & Fraternité – Belgium

FIAN Belgium – Belgium

CIDSE – Belgium

Friends of the Earth Europe – Belgium

Associação Brasileira de Reforma Agrária – Brazil

SOS Chapada dos Veadeiros – Brazil

Movimento Ciencia Cidadã – Brazil

CAPINA – Cooperação e Apoio a Projetos de Inspiração Alternativa – Brazil

Terra de Direitos – Brazil

Comissão Pastoral da Terra – Brazil

Amigos da Terra Brasil – Brazil

FAOR – Fórum da Amazônia Oriental – Brazil

FASE – Solidariedade e Educação – Brazil

IPDMS – Instituto de Pesquisa, Direitos e Movimentos Sociais – Brazil

Rede Jubileu Sul – Brazil

Via Campesina – Brazil

Emater – Brazil

Campaign in Defense of the Cerrado – Brazil

Réseau des acteurs du développement durable (RADD) – Cameroon

Synaparcam – Cameroon

REFEB – Côte d’Ivoire

DIOBASS Platform – Democratic Republic of Congo

Réseau d’information et d’appuis aux ONG en République démocratique du Congo (RIAO-RDC) – Democratic Republic of Congo

Acción Ecológica – Ecuador

Confédération paysanne – France

CCFD-Terre Solidaire – France

Les Amis de la Terre – France

Attac France – France

Survie – France

Muyissi Environnement – Gabon

FIAN Germany – Germany

APVVU – India

Indian Social Action Forum – India

Growthwatch – India

Karavali Karnataka Janabhivriddhi Vedike – India

Sahanivasa – India

Bina Desa – Indonesia

KRuHA – Indonesia

SNI – Indonesia Fisherfolk Union – Indonesia

Suluh Muda Inspirasi – Indonesia

GERAK LAWAN – Indonesia

Serikat Tani Merdeka (SETAM) – Indonesia

Front Perjuangan Pemuda Indonesia (FPPI) – Indonesia

Indonesia for Global Justice – Indonesia

Koalisi Rakyat Untuk Keadilan Perikanan (KIARA) – Indonesia

Solidaritas Perempuan – Indonesia

Global Legal Action Network – Ireland

Trócaire – Ireland

SONIA for a Just New World – Italy

Africa Japan Forum – Japan

Africa Rikai Project – Japan

Eriko Yano – Japan

Network between Village and Town – Japan

Japan International Volunteer Center (JVC) – Japan

Friends of the Earth Japan – Japan

Missionary Society of Saint Columban – Japan

WE21 Japan – Japan

Indigenous Strategy & Institution for Development – Kenya

SOS FAIM- Luxembourg

Collectif pour la défense des terres malgaches – TANY – Madagascar/France

Milieudefensie – Netherlands

Pakistan Kissan Rabita Committee – Pakistan

Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas – Philippines

Organización Boricuá de Agricultura Ecológica de Puerto Rico, CLOC-LVC – Puerto Rico

Kamara Organic Promoter – Rwanda

La Via Campesina South Asia – South Asia

Korea Women Peasants’ Association – South Korea

Bread for all – Switzerland

Generation Engage Network – Uganda

Corner House – United Kingdom

Global Justice Now – United Kingdom

Friends of the Earth United States – United States

The Oakland Institute – United States

Thousand Currents – United States

Grassroots International – United States

Family Farm Defenders – United States

National Family Farm Coalition – United States

Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID) – International

GRAIN – International

Biofuelwatch – International

World Rainforest Movement – International

Original source: Collective statement

Related posts:

You may like

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Seizing the Jubilee moment: Cancel the debt to unlock Africa’s clean energy future

Published

7 days agoon

July 12, 2025

Africa has the resources and the vision for a just energy transition, but it is trapped in a financial system structured to take more than it gives. In this blog, we outline how debt burdens and climate impacts are holding the continent back, and looks at the role of institutions that shape the global financial order, like the World Bank, African Development Bank and IMF. As these institutions and governments meet in Seville for FfD4, we urge them to heed people’s calls for reform: cancel the debt, redistribute the wealth, and fund the just transition. — By Rajneesh Bhuee and Lola Allen

With 60% of the world’s best solar energy resources and 70% of the cobalt essential for electric vehicle batteries, the African continent has everything it needs to power its development and become a global reference point for sustainable energy production. That potential, however, remains largely untapped; Africa receives just 2% of global renewable energy investment. As the UNCTAD Secretary-General Rebeca Grynspan warns, too many countries are forced to “default on their development to avoid defaulting on their debt.”

The cost of servicing unsustainable debts, layered with new loan-based climate and development finance, leaves governments with little fiscal space to invest in clean energy, health or education. In 2022 alone, African countries spent more than $100 billion on debt servicing, over twice what they spent on health or education. Add to this the $90 billion lost annually to illicit financial flows, and the reality is stark: more money leaves the continent through financial leakages (also including unfair trade and extractive investment) than comes in through productive, equitable and development-oriented finance.

These are not isolated problems. They reflect a financial system that has been built to serve global markets rather than people. Between 2020 and 2025, four African countries defaulted on their external debts, that is, they failed to make scheduled repayments to creditors like the International Monetary Fund or bondholders, triggering fiscal crises and, in several cases, IMF interventions tied to austerity measures. Pope Francis’ Jubilee Report (2025) and hundreds of civil society groups argue that these defaults reflect the deeper crisis of unsustainable debt. Meanwhile, 24 more African countries are now in or near debt distress. None have successfully restructured their debts under the G20 Common Framework, a mechanism launched in 2020 to facilitate debt relief among public and private creditors. The Framework has been widely criticised for being slow, opaque and ineffective. According to Eurodad, without urgent systemic reforms, up to 47 Global South countries, home to over 1.1 billion people, face insolvency risks within five years if they attempt to meet climate and development goals.

How debt undermines the just energy transition

Debt has become both a driver and a symptom of climate injustice. Countries that did the least to cause the climate crisis now pay the highest price, twice over. First, they suffer the impacts. Second, they must borrow to rebuild.

This is happening just as concessional finance disappears. The US has withdrawn from the African Development Fund’s concessional window (worth $550m), yet maintains influence over private-sector lending. It has also opted out of the UN Financing for Development Conference (FfD4), a historic opportunity to confront the injustice of our financial system. Meanwhile, European governments, though now celebrating themselves as defenders of multilateralism, played a key role in weakening the outcome of FfD4, slashing aid budgets, redirecting funds toward militarisation, and systematically blocking proposals for a UN-led sovereign debt workout mechanism. With rising insecurity and geopolitical tensions, these actions send a troubling signal: at a moment when global cooperation is urgently needed, many Global North countries are stepping back from efforts to fix the very system that is preventing climate justice and clean energy for much of the Global South.

A role for the AfDB?

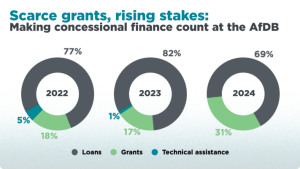

The African Development Bank (AfDB), under incoming president Sidi Ould Tah , has made progressive commitments of $10 billion to climate-resilient infrastructure and $4 billion to clean cooking. Between 2022 and 2024, one in five (20%) of its energy dollars were grants, far exceeding The World Bank ‘s 10% and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) ‘s 3.8%. The AfDB has also backed systemic reform: for example, calling for Special Drawing Rights (SDR) redistribution, launching an African Financial Stability Mechanism that could save up to $20 billion in debt servicing, and consistently advocating for fairer lending terms.

Yet, even progressive leadership struggles within a broken system. Recourse’s recent research shows that AfDB energy finance dropped 67% in 2024, from $992.7 million to just $329.6 million. Of this, a staggering 73% went to large-scale infrastructure like mega hydro dams and export-focused transmission lines, ‘false solutions’ that bypass the energy-poor and displace communities. Meanwhile, support for locally-appropriate, decentralised renewable energy systems such as mini-grids, solar appliances, and clean cookstoves plummeted by over 90%, from $694.5 million to just $61 million, with only five of 13 projects directly addressing energy access in 2024.

Africa received just 2.8% of global climate finance in 2021–22, and what is labelled as “climate finance” is often little more than a Trojan horse: resource-backed loans, debt-for-nature swaps, and blended finance instruments that shift risk to the public while offering little real benefit to local communities. These mechanisms, promoted as “innovative” or “green”, often entrench financial dependency and fail to deliver meaningful change for energy-poor or climate-vulnerable groups.

Meanwhile, initiatives that could build green industry and renewable capacity across Africa are falling short in both scale and speed. Flagship projects, such as the EU’s Global Gateway, have failed to drive green industrialisation in Africa, and carbon markets continue to delay real emissions reductions, subsidise fossil fuel interests, and entrench elite control over land and resources.

Mission 300: Ambition or another missed opportunity?

In this constrained context, the AfDB and World Bank launched Mission 300, an ambitious plan to connect 300 million Africans to electricity by 2030. Pragmatic goals like electrification are crucial, but the story beneath the surface of Mission 300 raises concern. Far from serving households, many projects under the initiative appear more aligned with export markets and large-scale energy users, echoing decades of infrastructure that bypasses those most in need.

Mission 300 can still be transformative, but only if it centres people, not profits. Energy access must begin with those who need it most: women and youth, especially in rural communities. Across Africa, many women cook over open fires, walk hours to gather fuel, and care for families in homes without light or clean air. This is not just an inconvenience, it is structural violence and policy failure.

Yet most energy finance still flows to centralised grids, mega-projects, and sometimes fossil gas (misleadingly called a “transition fuel”). These do little to address energy poverty. Locally appropriate decentralised renewable energy solutions, solar-powered appliances, clean cookstoves, and mini-grids can deliver faster, cheaper, and more equitable impact. Mission 300 must invest in such solutions, without adding to existing debt problems. It should support national policy design, for example, by ensuring that energy policy is responsive to women’s needs, making use of gender-disaggregated data and community consultation.

The Jubilee: A year for action

In a year already marked as a Jubilee moment, African leaders have demanded reform: including a sovereign debt workout mechanism and a UN Tax Convention to end illicit financial flows. Yet as AFRODAD has documented, these demands were blocked at the FfD4 negotiations by wealthy nations—notably the EU and UK—even as climate impacts grow and fiscal space shrinks.

This is not just about finance. It is about reclaiming sovereignty. The incoming AfDB president and all the multilateral development banks face a choice: continue financing extractive, large-scale projects that serve foreign interests, or invest in decentralised, gender-responsive, pro-people solutions that shift power and ownership.

Africa has the resources. What it needs is fiscal space, public-led finance, and global rules that prioritise people and planet over profit. The Jubilee call is clear: cancel the debt, redistribute the wealth, and fund the just transition.

Source: Recourse through LinkedIn Account Recourse.

Related posts:

Statement: The Energy Sector Strategy 2024–2028 Must Mark the End of the EBRD’s Support to Fossil Fuels

Statement: The Energy Sector Strategy 2024–2028 Must Mark the End of the EBRD’s Support to Fossil Fuels

African Development Bank decides not to fund Kenya coal project

African Development Bank decides not to fund Kenya coal project

Africa must unlock the power of its women to save climate change

Africa must unlock the power of its women to save climate change

PFZW scraps funding from Total and others for failure to transition into a cleaner energy mix.

PFZW scraps funding from Total and others for failure to transition into a cleaner energy mix.

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

Published

2 weeks agoon

July 8, 2025

Special report by the dedicated and thorough Witness Radio team, offering a comprehensive and in-depth overview of the situation.

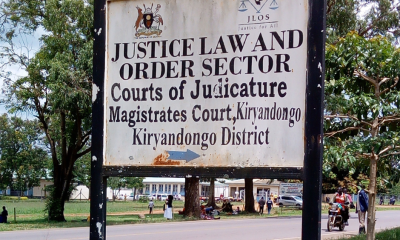

As Uganda moves forward with the controversial East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), a wave of arrests, intimidation, and court cases has targeted youth and environmental activists opposing the project. However, there is a noticeable and encouraging shift within Uganda’s justice systems, with a growing support for the protesters, potentially signaling a change in the legal landscape.

The EACOP project, stretching 1,443 kilometers from Uganda to Tanzania, has been hailed by the government as a development milestone. However, human rights groups and environmental watchdogs have consistently warned that the project poses serious risks to communities, biodiversity, and the climate. Concerns over land grabbing, inadequate compensation, and ecological degradation have mobilized a new generation of Ugandan activists.

Since 2022, as opposition to EACOP grew louder, Ugandan authorities have intensified a campaign of arrests and legal harassment. Police, military, and currently the Special Forces Command, a security unit tasked with protecting Uganda’s president, have been involved in brutal crackdowns on these activists.

Yuda Kaye, the mobilizer for students against EACOP, believes the criminalization is an attempt by the government to weaken their cause and silence them from speaking out about the project’s negative impacts.

“We are arrested just for raising the project concerns, which affect our future, the local communities, and the environment at large. Oftentimes, we are arrested without reason. They just round us up at once and brutally arrest us, Mr. Kaye reveals, in an interview with Witness Radio’s research team.

Activists have faced a litany of charges, including unlawful assembly, incitement to violence, public nuisance, and criminal trespass. Many of these charges have lacked substantive evidence and have been dismissed by the courts or had their files closed by the police after prolonged delays.

A case review conducted by Witness Radio Uganda reveals that Uganda’s justice system is being used to suppress the activities of youth activists opposing the project, rather than convicting them. However, despite the system being used to silence them, it has often found no merit in these cases.

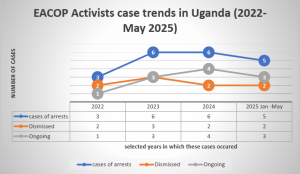

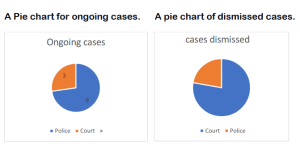

Of a sample of 20 documented cases since 2022 involving the arrest of over 180 activists, 9 case files against the activists have either been dismissed by courts or closed by the police due to a lack of prosecution, another signal indicating the relevance of their work, while 11 cases remain ongoing.

The chart below shows trends in arrests, dismissed cases, and ongoing cases involving EACOP activists in Uganda from 2022 to May 2025.

The review was conducted with support from the activists themselves and their lawyers. It involved a desk review and analysis of Witness Radio articles concerning the arrests of defenders and activists opposing the EACOP project.

Witness Radio’s analysis reveals a concerning trend as the majority of cases involving these activists are stalling at the police level rather than progressing to the courts of law. This suggests that the police have not only criminalized activism but are also playing a syndicate role in deliberately prolonging these cases under the excuse of ongoing investigations.

“While both the police and judiciary are being used to suppress dissent, the courts have at least demonstrated a degree of fairness, having dismissed at least 78% of cases that fall within their jurisdiction. In contrast, the police continue to hold 73% of activist cases in limbo, citing investigations as justification for indefinite delays.” The research team discovered.

Witness Radio’s analysis further shows that in most of these cases, the state has failed to produce witnesses or evidence to convict the activists, adding that the charges are often just tools of intimidation. Additionally, this is accompanied by more extended periods during which decisions are being made.

Despite the intense crackdown, it is evident that these activists are winning, as no proven record of sentencing has been observed. Instead, these cases are often marred by delays in court or at the police, and in the end, some have been dismissed. This implies that protest marches and petition deliveries serve a purpose; the state just needs to listen to their concerns and formulate possible solutions to address them,” said Tonny Katende, Witness Radio Uganda’s Research, Media and Documentation Officer.

According to Article 29(1)(d) of the Constitution of Uganda, every individual has the right to “assemble and demonstrate together with others peacefully and unarmed and to petition.” Additionally, Article 20 emphasizes that fundamental rights and freedoms “are inherent and not granted by the State.” Yet activists report that police regularly deny them the right to exercise their rights as guaranteed.

At a February 2025 press conference, EACOP activists strongly condemned the police’s continued unlawful arrests of demonstrators exercising their constitutional rights and case delays. This followed escalating crackdowns that added to the tally of over 100 activists arrested in 2024 alone.

“We strongly condemn these arrests. Detaining demonstrators does not address the concerns affecting grassroots communities impacted by oil and gas projects,” declared the group, led by Bob Barigye, who remains in prison on another charge still linked to his opposition to EACOP.

An interview with Mr. Yuda Kaye, a mobilizer from the Students Against EACOP Movement, confirmed that the ongoing dismissals only reaffirm the legitimacy of their resistance.

“These cases are dismissed because the government and its justice systems don’t have any grounds to convict us. This justifies the fact that the issues we’re discussing are real. We only seek accountability, but since the government has power, they criminalize us and silence us,” Mr. Kaye added.

According to Kaye, the intimidation is real, but so is their commitment. “We are called enemies of progress, but we’re only protecting our future and that of our country. We’ve often proposed alternatives, but the government doesn’t want them.” He re-echoes.

Despite this, activists say their rights are routinely violated. Witness Radio Uganda attempted to contact the police spokesperson, Mr. Kituuma Rusooke, but known numbers were unreachable, and messages sent to him went unanswered.

In a separate interview with Mr. James Eremye Mawanda, the Judiciary Spokesperson, he acknowledged the pattern of dismissals and delays.

“As the Judiciary, we listen to cases, and where there is no evidence to support the case, a decision is made. When a crime is allegedly committed and an individual is brought before the court, the courts upholding the rule of law shall administer justice,” he said.

According to Witness Radio’s analysis, 2025 has seen the most dismissals so far, with six cases concluding, reinforcing the view that criminalization is used more for intimidation than as a means of legal redress. “Whereas the arrests took place in separate years, most of the dismissals have happened in 2025,” the research team further highlighted.

Mr. Brighton Aryampa, the team lead of Youth for Green Communities, one of the organizations that provide legal representation for Stop-EACOP activists, highlighted that the criminalization of Ugandan activists undermines Uganda’s democratic principles of free expression and open discourse.

“The government, in bed with oil corporations Total Energies and CNOOC, is deliberating using legal action against Stop EACOP activists to suppress dissent, free speech, right to peaceful protest, and against public participation. This is tainting Uganda as a country that undermines the democratic principles of free expression and open discourse, as hundreds of Stop EACOP activists have been arrested, charged, and some tried by a competent court. However, no one has been found guilty of the fabricated offense usually slapped on them.” He said in an interview with Witness Radio.

Counsel Aryampa further advised that the practice of powerful companies and businesses blackmailing and corrupting the Ugandan government to develop harmful projects while ignoring all social warnings and human rights abuses must be stopped.

The pressure exerted by these activists, both locally and internationally, has slowed the EACOP project. It has also led to bankers and insurers withdrawing from financing or insuring the project. According to Stop EACOP campaigners, more than 40 international banks and 30 global insurance firms, including Chubb, have distanced themselves from the controversial pipeline project, citing human rights and climate concerns raised by these activists.

Meanwhile, as the activism grows, the number of arrests is rising. Within just the first six months of 2025, over 40 activists have been criminalized for their activism. Among them is KCB 11, a group of eleven activists that was arrested at the KCB offices in April 2025. The group has spent over two months on remand, despite their lawyers’ pleas for bail to be granted.

Related posts:

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

EACOP: The trial of 20 environmental activists failed to take off, and now they want the case dismissed for lack of prosecution.

EACOP: The trial of 20 environmental activists failed to take off, and now they want the case dismissed for lack of prosecution.

Milestone: Another case against the EACOP activists is dismissed due to the want of prosecution.

Milestone: Another case against the EACOP activists is dismissed due to the want of prosecution.

The latest: Another group of anti-EACOP activists has been arrested for protesting Stanbic Bank’s financing of the EACOP Project.

The latest: Another group of anti-EACOP activists has been arrested for protesting Stanbic Bank’s financing of the EACOP Project.

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

‘Left to suffer’: Kenyan villagers take on Bamburi Cement over assaults, dog attacks

Published

4 months agoon

March 22, 2025

- The victims are aged between 24 and 60, and one of them has since passed on.

- Many were severely injured and hospitalized following brutal attacks, unlawful detention, and physical assault by Bamburi’s security personnel.

Editor’s note: Read the petition here.

Their hopes for justice seemed to be slipping away after initially taking on a multinational corporation and failing to hold it accountable for the brutal injuries they suffered.

The death of one of their own cast a shadow of despair, making it seem unlikely that they would ever bring the corporation to justice for the crimes they alleged.

However, 11 victims of dog attacks, assaults, and other severe human rights violations are now challenging Bamburi Cement PLC’s role in these abuses in court.

They are represented by the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC), which on January 29, 2025, filed a legal claim before a constitutional court in Kenya, seeking to hold the multinational accountable for the harm suffered by the victims—residents of land parcels in Kwale that Bamburi claims ownership of. KHRC worked with the Kwale Mining Alliance (KMA) to bring this case.

The victims, aged between 24 and 60, include Mohamed Salim Mwakongoa, Ali Said, Abdalla Suleiman, Hamadi Jumadari, Abdalla Mohammed, and Omari Mbwana Bahakanda. Others are Shee Said Mbimbi, Omar Mohamed, Omar Ali Kalendi (deceased), Abdalla Jumadari, and Bakari Nuri Kassim.

Bamburi had hired a private security firm and deployed General Service Unit (GSU) officers to guard three adjoining land parcels, covering approximately 1,400 acres in Denyenye, Kwale. The GSU established a camp on the land, which has historically been accessed by residents who have long used established routes to reach the forest and the Indian Ocean.

For decades, these routes provided them with access to resources such as firewood, crops, and fish, which they relied on for their livelihoods. However, five years ago, when they attempted to collect firewood, harvest crops, and access the ocean through the land, Bamburi accused them of trespassing. The company’s private guards and GSU officers responded with force, setting dogs on them and assaulting them.

Many were severely injured and hospitalized following brutal attacks, unlawful detention, and physical assault by Bamburi’s security personnel. These incidents occurred despite the lack of clearly defined boundaries and the fact that the traditional access routes had never been contested.

According to the petition, GSU officers and private guards inflicted serious injuries by kicking, punching, and beating the victims with batons. Those who were arrested were neither taken to a police station nor charged with any offense. Despite their injuries, they were denied emergency medical care.

These actions were intended to intimidate residents, prevent them from accessing the beach, and suppress any historical claims to the land, the victims tell the court. Local police in Kwale failed to investigate the abuses, visit the crime scenes, or arrest any of the perpetrators, they add.

Now, the victims are seeking compensation for these violations. They have also asked the court to declare that their rights were violated through torture inflicted by Bamburi’s guards and GSU officers. Additionally, they want the court to rule that releasing guard dogs to attack them during arrests constituted an extreme and unlawful use of force.

Source: khrc.or.ke

Related posts:

Breaking: Over 600 attacks against defenders have been recorded in the year 2023 globally- BHRRC report.

Breaking: Over 600 attacks against defenders have been recorded in the year 2023 globally- BHRRC report.

Kaweeri Coffee land grabbing case re-trial resumes as evictees continue to suffer gross human rights violations.

Kaweeri Coffee land grabbing case re-trial resumes as evictees continue to suffer gross human rights violations.

Criminalization of planet, land, and environmental defenders in Uganda is on the increase as 2023 recorded the soaring number of attacks.

Criminalization of planet, land, and environmental defenders in Uganda is on the increase as 2023 recorded the soaring number of attacks.

Local land grabbers evict villagers at night; foreign investors cultivate the same lands the next day

Local land grabbers evict villagers at night; foreign investors cultivate the same lands the next day

A land rights defender and his wife have been arrested, charged, and sent to prison.

Land Grabbing Crisis Escalates in Uganda: Mayiga Urges Citizens to Secure Land Documents

Seizing the Jubilee moment: Cancel the debt to unlock Africa’s clean energy future

Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

A decade of displacement: How Uganda’s Oil refinery victims are dying before realizing justice as EACOP secures financial backing to further significant environmental harm.

Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

Govt launches Central Account for Busuulu to protect tenants from evictions

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

- PRESENDIANTIAL DIRECTIVE BANNING ALL LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA

- FROM LAND GRABBERS TO CARBON COWBOYS A NEW SCRAMBLE FOR COMMUNITY LANDS TAKES OFF

- African Faith Leaders Demand Reparations From The Gates Foundation.

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks agoActivism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

-

DEFENDING LAND AND ENVIRONMENTAL RIGHTS3 days ago

DEFENDING LAND AND ENVIRONMENTAL RIGHTS3 days agoA land rights defender and his wife have been arrested, charged, and sent to prison.

-

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS7 days ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS7 days agoSeizing the Jubilee moment: Cancel the debt to unlock Africa’s clean energy future

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days agoLand Grabbing Crisis Escalates in Uganda: Mayiga Urges Citizens to Secure Land Documents