MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Insights for African countries from the latest climate change projections

Published

4 years agoon

Flooding is projected to increase in eastern Africa

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – a body of the UN tasked with providing scientific information on climate change – has released a major new report, pulling together evidence from a wide range of current and ancient climate observations. It’s the most up-to-date understanding of climate change, bringing together the latest advances in climate science.

It is crucial that we have a good understanding of the findings as they give an indication of what our future could look like.

According to the report global warming is evident, with each of the last four decades being successively warmer than any decade that preceded it since 1850. Average precipitation on land has also increased since the mid-20th century. In addition, there is high confidence that mean sea level increased by between 0.15 and 0.25m between 1901 and 2018.

The major concern is that as warming continues, more extreme climate events, such as droughts, are projected to increase in both frequency and intensity. This warming is mainly driven by greenhouse gas emissions from human activities such as burning fossil fuels (coal, natural gas, and oil) and coal production.

Get news that’s free, independent and based on evidence.

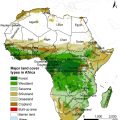

When it comes to African countries, the report projects an increase in average temperatures and hot extremes across the continent. The continent will likely experience drier conditions with an exception of the Sahara and eastern Africa.

Alarmingly, the rate of temperature increase across the continent exceeds the global average. In addition, as warming continues, the frequency and intensity of heavy rainfall events are projected to increase almost everywhere in Africa. Maritime heatwaves and sea level rises are also projected to increase along the continental shores.

Looking into the future, global warming could lead to an increase in hot extremes, including heatwaves. It could also lead to a decrease in cold extremes.

The projected dry and hot conditions will have a devastating impact on a continent where the economies of most countries, and the livelihoods of most people, are dependent on rain-fed agriculture. In fact, changes to the climate will affect almost all parts of our lives.

Regional impacts

In a scenario where global warming will reach at least 2°C by mid-21st century (as predicted by the report), southern Africa is highly likely to experience a reduction in mean precipitation (water vapour that falls, such as rain or drizzle or hail). This will adversely affect agriculture. Specifically, the region is likely to witness an increase in aridity, and droughts. We are already seeing this in Madagascar and South Africa.

This has serious implications for all sectors including agriculture, water and health. Drought would also likely reduce hydroelectric generation potential, adversely affecting energy dependent sectors. We are already seeing this at the Kariba dam which sits between Zimbabwe and Zambia.

In addition, there will be more tropical storms in the region. In southern Africa there’s been a southward shift in the occurrence of tropical cyclones. This is due to sea temperatures increasing as a result of global warming. The concern is that these events will be particularly destructive as seen in Madagascar and over Mozambique.

Read more: Rising sea temperatures are shaping tropical storms in southern Africa

In relation to eastern Africa, the report projected an increase in mean precipitation that favours agriculture. However, increases in the frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation and flooding may cause a counter effect in some areas, such as arid and semi-arid lands.

There has been some conflicting information regarding rainfall in eastern Africa. This follows observations that the general circulation models, used in preparation of IPCC reports, do not simulate the observed rainfall well over the region. Most models project increase in rainfall while observations report the opposite. This has been termed ‘the paradox of east Africa climate’. This observed shortening of rainfall season that is not captured by the models explains the paradox.

Besides rainfall, the recorded and projected temperature which is expected to increase will decrease the snow and glaciers in the region. A rise in temperatures will result in a rise in malaria cases especially in highland areas within the region.

Northern Africa is a climate change hotspot. The report anticipates with high confidence increase in temperatures in the region,causing extreme heatwaves. Projected drying will increase aridity that already begun to emerge in the region and worsen water scarcity.

Read more: A worsening water crisis in North Africa and the Middle East

Further, the situation will increase the risk of forest fires, a threat to ecosystems. As is currently seen in Algeria where, so far this year, more than 100 fires have been reported across 17 provinces, killing over 40 people.

The report also anticipated that there will be a reduction in mean wind speed over northern Africa. The wind speed is dependent on temperature and consequently atmospheric pressure changes. This will limit the region’s wind power potential, however – on a positive note – it will equally reduce dust storms that cause health impacts, such as causing and aggravating asthma, and bronchitis.

Similarly, west and central Africa are projected to record a reduction in mean precipitation and experience more agricultural and ecological droughts. All these cast a dark cloud on agriculture and water in the region.

Read more: Lagos is getting less rain, but more heavy storms. What it can do to prepare

Along the African coastlines, the relative sea-level rise is likely to contribute to an increase in the frequency and severity of coastal flooding in low-lying areas, like the recent cases in Lagos, Nigeria. This causes massive destruction to delicate coastal ecosystems and will displace communities that live in coastal towns. The sea level rise equally causes saltwater intrusion, limiting availability of fresh water.

Read more: Climate change is affecting agrarian migrant livelihoods in Ghana. This is how

Which way for Africa?

Despite the projection of decrease in mean precipitation over nearly all the regions of Africa, heavy precipitation and pluvial flooding is likely. The increase in wet extremes has far reaching effects on nearly all socioeconomic sectors, from agriculture, water, environment to infrastructure. These are some of the key sectors in socioeconomic development.

This – compounded by growing populations – gives a worrying picture of the challenges that lie ahead. This is likely to widen the existing development gap, calling for concerted effort to strengthen response mechanisms to future challenges posed by climate change.

Original Source: The conversation

Related posts:

Climate change has reduced agricultural productivity by 34 percent in Africa

Climate change has reduced agricultural productivity by 34 percent in Africa

Africa warming faster than rest of world: IPCC Sixth Assessment Report

Africa warming faster than rest of world: IPCC Sixth Assessment Report

Africa must unlock the power of its women to save climate change

Africa must unlock the power of its women to save climate change

African women unite on the frontlines of the Climate Crisis

African women unite on the frontlines of the Climate Crisis

You may like

-

Africa warming faster than rest of world: IPCC Sixth Assessment Report

-

WWF launches new impact platform that engages businesses and investors to deliver on sustainability ambitions

-

Tropical forests in Africa’s mountains store more carbon than previously thought—but are disappearing fast

-

Finnish carbon offsetting firm Compensate finds 91% of carbon offset projects fail its evaluation process. Of course the remaining 9% will also not help address the climate crisis

-

Water hyacinth threatens Lake Victoria’s ecosystem

-

Put people above profits – Climate Activists urge Total to defund EACOP

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

UPDF General on the spot over fresh evictions in Hoima

Published

1 day agoon

February 17, 2026

Over 1,000 residents in Kapapi Sub-County, Hoima District, are facing a second forced eviction from their ancestral land in three years, sparking widespread tension and anger among the community.

The latest evictions have been linked to a senior Uganda Peoples’ Defence Forces (UPDF) officer, Brigadier General Peter Nabasa, whom residents accuse of masterminding the displacement, allegedly in defiance of earlier government directives issued by the state minister for Lands, Dr. Sam Mayanja.

In October 2025, Minister Mayanja ordered that over 1,000 families who had been evicted from contested land in Kapapi Sub-County be resettled back onto their bibanja.

He also directed security commanders in the area to withdraw armed personnel and allow the affected communities to return. However, residents claim the situation has worsened, with renewed evictions pushing thousands into uncertainty once again.

The affected families, estimated to be over 1,000 and comprising over 4,000 people, include both cultivators and pastoralists. They were evicted from their homes in several villages, including Waaki North, Kapapi Central, Waaki South, Runga, Kiryatete, and Kiganja, all located in Kapapi and Kiganja sub-counties, Hoima District.

Residents insist the land has been their home for decades, passed down through generations, and accuse powerful individuals of using land titles and security enforcement to displace them.

“We were returned to our land in October last year on the orders of President Museveni and Minister Mayanja, but shortly after the elections, we were evicted again,” said Deusi Mugume, a resident of Runga.

“The Brigadier General came with armed security personnel and ordered us to vacate the land immediately. They even fired bullets in the air to disperse us, disrespecting the orders of both the Minister and the President.”

The residents were evicted from two titled pieces of land said to belong to businessmen and private individuals based in Hoima and Kampala. One of the contested titles measures approximately 2,545 acres (1,030 hectares) and is reportedly owned by seven individuals, including Ndahura William Gafayo, Aston Muhwezi, Alex Kyamanywa, Nathan Kiiza Byarugonjo, Bahuzya, Monica Rwashadika, and Wilber Kiiza. This land reportedly covers parts of Kapapi and Kiganja sub-counties.

Another title, measuring about three square miles, is said to belong to the family of the late Tito Byangire of Kigorobya, Hoima District. This land reportedly covers four villages, including Waaki South, Waaki North, Runga, Kapapi Central, and Kiryatete.

Brig Gen Nabasa claims he legally leased 700 acres of land from the Byangire family for 10 years starting in 2023.

“The residents were allowed to live there temporarily because elections were approaching, but they were supposed to leave immediately after the polls,” he said.

The residents, who are now living in temporary structures in Rwenyana, say their food and cash crops were destroyed after cattle were introduced onto the land following their eviction.

“We are going through many difficulties. We have no food, we are sleeping in makeshift shelters, children are not going to school, and we don’t know if we shall ever return to our land,” said Madinah Nyanjura and Nyarabiraho Cheya, both residents of Kapapi.

The Hoima Deputy Resident District Commissioner, Christopher Aine, blamed land brokers for misleading residents and bringing more people onto the contested land.

Minister Mayanja had previously directed the arrest of Brig Gen Peter Nabasa, Capt Rogers Karamagi, former Hoima Deputy Resident District Commissioner Michael Muramira Kyakashari, and William Ndahura Gafayo for allegedly illegally evicting residents from their bibanja land.

Mr Joshua Byangire, one of the administrators of the late Byangire estate, said the family has faced continued disruption and appealed to the government to buy off the land title.

“We have been disturbed on our family land. I request the government to buy off our land title. I don’t understand why soldiers have been deployed there, yet we are civilians and cannot access our property,” he said.

Original Source: monitor.co.ug

Related posts:

Breaking: The army general, police chief, presidential representative, and others are appearing before the Hoima Chief Magistrate court today.

Breaking: The army general, police chief, presidential representative, and others are appearing before the Hoima Chief Magistrate court today.

Court issues fresh criminal summonses against army general, police chief and presidential representative and others in a private criminal case.

Court issues fresh criminal summonses against army general, police chief and presidential representative and others in a private criminal case.

Over 500 Kapapi families in Hoima district remain stranded after the district security committee fails to resettle them back on their land as directed by the minister.

Over 500 Kapapi families in Hoima district remain stranded after the district security committee fails to resettle them back on their land as directed by the minister.

UPDF General, District Police Commander, and Presidential Representative defy Court summonses for the second time as DPP takes over the EACOP-PAP’s case.

UPDF General, District Police Commander, and Presidential Representative defy Court summonses for the second time as DPP takes over the EACOP-PAP’s case.

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Small-scale fishers and coastal communities are pushing to testify before a human rights commission investigating the causes of food inequality in South Africa.

Published

1 day agoon

February 17, 2026

Fisher women play a vital role in sustaining household food security, yet remain under‑recognised, excluded from permits, and denied equal income opportunities in the fishing sector.Photo Credit: The Green Connection.

By Witness Radio team.

South Africa produces enough food to feed its population, yet millions go to bed hungry every night.

According to Statistics South Africa’s General Household Survey 2024, released in 2025, about 14 million people experienced hunger, representing 22.2% of households reporting inadequate or severely inadequate access to food. The Northern Cape (34.3%), Eastern Cape (31.3%), and Mpumalanga (30.4%) recorded the highest levels of food insecurity.

One in four children in South Africa is stunted due to chronic malnutrition. In the Eastern Cape alone, 70 children under the age of five reportedly died from malnutrition-related complications between January and July 2025.

In response to the growing problem, the South African Human Rights Commission, a national institution established to support constitutional democracy, declared last year that it would hold a National Public Inquiry into the Constitutional Right to Food. This inquiry will examine how communities, corporations, laws, and policies shape food systems and seek to address the structural causes of hunger.

As a result, the investigation will try to describe a future in which food is once again understood as sustenance, dignity, and justice.

Thousands of small-scale fishers along South Africa’s 3,000 km coastline depend on marine resources for their livelihoods, highlighting their vital role in the nation’s food security and cultural fabric.

Many fishing families struggle to make ends meet, even though they harvest food from the ocean. The livelihoods and food security of about 28,000 small-scale fishermen are directly reliant on marine resources. Yet, existing policies-such as restrictive permits and limited market access-exclude them from full participation, perpetuating food insecurity.

For these communities, food systems are not abstract policy concepts. They shape daily survival, dignity, livelihoods, and cultural identity.

“As part of our submission, we emphasize that concrete policy changes-such as recognizing customary fishing rights and improving market access-will directly enhance the livelihoods and food security of small-scale fishers and coastal communities, making the case for urgent reform.” Says Buthelezi

The Green Connection, a registered non-profit organisation, works with coastal communities to promote environmental justice, human rights, and accountable governance.

In the submission, the Green Connection states that the inquiry is timely as it will examine the structural and economic dynamics that perpetuate hunger. “It will assess the concentration of power in the food value chain, affordability and access, land and tenure security, policy coordination, and the realization of the constitutional right to food. This includes its links to dignity, health, water, culture, and a healthy environment.” The submission reads.

The Green Connection further argues that the Commission’s examination of governance, participation, and accountability must include scrutiny of marine and ocean policy.

“Poor implementation of the Small-Scale Fisheries Policy, limited market access, inadequate infrastructure, and weak consultation processes continue to undermine the sector. Women – who make up less than 30% of participants – remain under-recognised. At the same time, young people leave coastal communities due to declining economic prospects,” says Khetha Buthelezi, Economics Officer at The Green Connection, adding that, “Food and the systems we put in place to produce it cannot be separated from human dignity, livelihoods, and cultural rights. These issues are not abstract policy debates. For small-scale fishing communities, food from the ocean is not merely a commodity – it is a foundation of identity, survival, and social cohesion.”

The organisation also raises concerns about the potential impacts of offshore oil and gas expansion under Operation Phakisa. It further adds that Seismic surveys, drilling, and increased shipping activity can threaten fish stocks and restrict access to traditional fishing grounds, thereby directly affecting food security and livelihoods.

“For small-scale fishers, these are not abstract environmental issues. It is about income stability, cultural survival, and the constitutional rights to food, livelihoods, and participation in decision-making, and protecting these rights and resources for future generations,” says Buthelezi

Several fishing communities consulted shared testimonies describing worsening conditions.

“While small‑scale fishers support around 28000 people in South Africa, many of us can no longer catch or sell enough fish to feed our own families. Walter Steenkamp says on behalf of Aukotowa Small‑Scale Fishers Co‑operative in Port Nolloth, Northern Cape.

Steenkamp adds that Decisions are often made without consulting them, which reflects an intended exclusion from decision-making. “We hope this inquiry will result in the recognition of our customary rights, the return of our fishing grounds, and for the government to listen to those of us who live from the sea, so that we can feed our families with dignity.”

According to Kristie Links from the Sal-Diaz Small-Scale Fisher Co-operative in Saldanha Bay, Western Cape, farmers are forced to use larger boats that they cannot afford. “We have no money for the bigger boats they want us to use, and the areas we are given have little or no fish.

Industrial boats continue to overfish, especially at night, while our communities struggle to put food on the table. This situation is destroying our livelihoods, our food security, and our right to be recognised as small-scale fishers,” Kristie adds.

The organisation argues that poor implementation of the Small-Scale Fisheries Policy, weak consultation processes, and inadequate infrastructure continue to undermine the sector.

“Our message to the SAHRC is clear. If South Africa is serious about tackling hunger and inequality, it must ensure food systems governance is transparent, inclusive, and accountable. Coastal communities are not asking for charity – they are demanding justice.” Buthelezi concludes

The deadline for written submissions has been extended to 27 February 2026, with public hearings scheduled for March during Human Rights Month.

Related posts:

About 41 million people food insecure in E. Africa amid COVID-19 pandemic: UN

About 41 million people food insecure in E. Africa amid COVID-19 pandemic: UN

63 million people food insecure in Horn of Africa: report

63 million people food insecure in Horn of Africa: report

“Vacant Land” Narrative Fuels Dispossession and Ecological Crisis in Africa – New report.

“Vacant Land” Narrative Fuels Dispossession and Ecological Crisis in Africa – New report.

Community land rights at stake amid looming large-scale investment interests

Community land rights at stake amid looming large-scale investment interests

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

The Kenyan government insists on maintaining provisions of the Seed Act that the court nullified: farmers and legal experts question the motive.

Published

2 days agoon

February 16, 2026

By Witness Radio team.

Mr. Francis Njiri, a small-scale farmer from Makongo and a member of the Seed Savers Network Kenya, questions the spirit behind the Kenyan government and the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service (KEPHIS) in appealing against the recent High Court ruling on seed rights, including saving and exchange.

The landmark judgment delivered in November 2025 declared key sections of the Seed and Plant Varieties Act unconstitutional, directly affirming farmers’ rights to save, share, and exchange seeds outside formal systems, which many smallholder farmers like Mr. Njiri see as a victory for traditional practices and their livelihoods.

15 smallholder farmers from the Seed Savers Network filed a constitutional petition in 2022, claiming that Kenya’s Seeds and Plant Varieties Act (SPVA) and the Seeds and Plant Varieties (Seeds) Regulations, 2016, have restrictive provisions that violate fundamental rights protected by Kenya’s Constitution, which the Kenya’s High Court in Machakos ruled in their favor.

According to court documents seen by Witness Radio, the Kenyan government and KEPHIS have appealedagainst the court ruling, claiming that the High Court judge misinterpreted key legal provisions, underscoring the ongoing legal battle over seed rights.

“Take notice that The Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service and The Attorney General, the above-named Appellants, appeal to the Court of Appeal against the whole of the above-mentioned decision,” documents seen by Witness Radio reveal.

“The Learned Judge erred in law and in fact by misinterpreting and conflating Sections 8(1) and 8A of the Seeds and Plant Varieties Act with Article 11(3)(b) of the Constitution, and by wrongly concluding that those provisions limit or undermine Section 27A, while in fact Sections 8(1), 8A and 27A operate harmoniously to give full effect to Article 11(3)(b) of the Constitution.

The Learned Judge erred in law and in fact by holding that Sections 8(1) and 10(4)(c), (d), (e), (f) and (g) of the Seeds and Plant Varieties Act, together with Regulations 6, 16 and 19 of the Seed and Plant Varieties (Seed) Regulations are unconstitutional based on discrimination under Article 27(2) of the Constitution, when no distinction had been demonstrated…” further reveals.

The government’s decision to appeal has alarmed farming communities and civil society, raising fears that their interests are being overlooked.

“I don’t think the government is working in the interests of farmers. We suspect these actions serve multinational corporations’ interests because farmers were not consulted in the first place.” Mr. Njiri says.

Mr. Njiri, who has practiced agroecological farming for years, is one of the petitioners in the case. Alongside other farmers from across the country, he challenged the constitutionality of provisions that restricted the use of farm-saved seeds. He argues that such laws disproportionately favored commercial seed companies while undermining indigenous seed systems that have sustained communities for generations.

According to him, the lack of consultation with smallholder farmers, who constitute the majority of Kenya’s agricultural producers, raises serious questions about whose interests are being prioritized.

For generations, farmers have saved, exchanged, and improved seeds-these practices are part of our heritage and vital for our survival. Decisions about seeds should involve those who depend on them most.

In the case that had been determined in favor of the local farmers, Advocate Wambugu Wanjohi says the Government of Kenya and KEPHIS were challenging mostly seed sovereignty, the right to save, share, and replant seeds, and the right to participate in seed policies.

“Now, the Seed and Plant Varieties Amendment Act aligned Kenya with UPOV of 1991, and seed exchange outside the normal certification process became illegal. And the consequence was that the government pushed indigenous seed systems underground.” He mentioned.

Wanjohi describes the High Court ruling as a constitutional milestone.

“This case was not simply about regulatory compliance. The Court approached it as a human rights matter. It examined whether criminalizing seed sharing unjustifiably limited constitutional rights such as the right to food, the protection of culture, equality, and fair administrative action,” he said.

“We argued on a constitutional basis. The farmers sought to have these sections declared unconstitutional because the Act and regulations unjustifiably limited the right to food and eroded cultural rights and equality.”

According to Wanjohi, the Court found that the impugned provisions disproportionately burdened smallholder farmers while privileging commercial seed interests.

“The Constitution does not permit legislation that effectively punishes the survival practices of small-scale farmers. The judgment reaffirmed that seed governance must align with constitutional protections,” he added.

Dr. David Kabanda, Director of the Center for Food and Adequate Living Rights in Uganda, views the ruling as significant beyond Kenya’s borders.

“Seed is not merely a commercial commodity; it is the foundation of food systems and community resilience. When laws shift control of seed away from farmers without meaningful participation, they raise fundamental legal and human rights questions,” Kabanda says.

He adds that the case introduces a constitutional perspective that could influence similar debates across East Africa, particularly in countries aligning seed laws with international intellectual property standards.

“Seed determines protection of our land, because in an ordinary African city, if you don’t have seed, then you cannot plant. Seed and food give land relevance in many communities. So, if someone takes our seed from you, especially in the current region where some countries, like Kenya, want to create what they call seed merchants and impose exorbitant fees on you to operate the seed trade or business, it is alienating people from the livelihood they should have. Because if any state or multinational takes away the seed, the propagating material, whether for food or agriculture, it is touching the nerve of your existence.” Kabanda added.

As the appeal process unfolds, farmers like Mr. Njiri say they remain committed to defending what they consider fundamental rights: the right to seed, the right to food, and the right to participate in decisions that directly affect their livelihoods.

“We will continue to stand firm. Seeds are our life. Without them, there is no farming, and without farming, there is no food. We will fight and fight and fight until we win. And we believe we shall win the entire battle. Because we wouldn’t let that freedom, which God gives, be taken away from us because someone wants to protect their interests or farmers’ interests,” he concluded.

With the government and KEPHIS appealing the High Court’s landmark decision, it is now more important than ever for judges, lawyers, and civil society across Africa to actively support farmers in defending their constitutional seed rights. “Strategic litigation has set a precedent on the continent, showing that courts can and must uphold food sovereignty and protect the rights of smallholder farmers.” Advocate Wanjohi added.

Related posts:

Kenyan farmers secure right to share local seeds in court ruling

Kenyan farmers secure right to share local seeds in court ruling

The EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025, is a potential threat to smallholder farmers, as it aims to disengage them from the agriculture business, according to experts.

The EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025, is a potential threat to smallholder farmers, as it aims to disengage them from the agriculture business, according to experts.

Seed Sovereignty: Most existing and emerging laws and policies on seeds are endangering seed saving and conservation on the African continent.

Seed Sovereignty: Most existing and emerging laws and policies on seeds are endangering seed saving and conservation on the African continent.

The Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network Joint Radio program boosts Farmers’ knowledge of seed and food sovereignty.

The Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network Joint Radio program boosts Farmers’ knowledge of seed and food sovereignty.

UPDF General on the spot over fresh evictions in Hoima

Small-scale fishers and coastal communities are pushing to testify before a human rights commission investigating the causes of food inequality in South Africa.

The Kenyan government insists on maintaining provisions of the Seed Act that the court nullified: farmers and legal experts question the motive.

FEATURE: What Lagos Can Learn From Kenya, Morocco, Uganda’s Forced Evictions

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Evicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks agoUS-DRC Strategic Partnership Agreement Faces Constitutional Challenge in Court

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoIndigenous communities’ complaint against World Bank-linked Nepal Cable Car Project declared eligible for investigation.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoDecades of land loss and chronic poverty: Salala Rubber Plantation prioritizes profit over the well-being of local Liberian communities.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoThe Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network Joint Radio program boosts Farmers’ knowledge of seed and food sovereignty.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoFEATURE: What Lagos Can Learn From Kenya, Morocco, Uganda’s Forced Evictions

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago13 years after the refugee host community was forcefully evicted to expand a refugee settlement, thousands remain unsettled.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days agoThe Kenyan government insists on maintaining provisions of the Seed Act that the court nullified: farmers and legal experts question the motive.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day agoSmall-scale fishers and coastal communities are pushing to testify before a human rights commission investigating the causes of food inequality in South Africa.