NGO WORK

African Civil Society Refuses To Engage With UNFSS Without Radical Change

Published

5 years agoon

Members of the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa

Dr. Agnes Kalibata

Special Envoy of the UN Secretary-General for the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit

Prerequisites for engaging with the UNFSS

Dear Dr. Kalibata

AFSA acknowledges your invitation of 17th September 2020 to be part of the champions group and represent African civil society. At first, we declined, for reasons set out below. However, after careful deliberation, we, the undersigned 36 network members of AFSA, came to a consensus that we would be prepared to engage with the United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS), scheduled to take place in September 2021 in New York, USA, dependant upon the UNFSS agreeing to the conditions set out below.

AFSA initially welcomed the UN Secretary-General’s announcement to convene the world Food Systems Summit in 2021 with profound hope and enormous optimism. The food systems transformation agenda is long overdue, and many social movements and civil society actors, in Africa and globally, have been fighting for systemic and structural transformation of food systems, stressing the urgent need for a radical shift from fossil fuel-based industrial agriculture and corporate monopolies of food and agriculture to food sovereignty and agroecology.

However, our genuine hope for a vibrant, inclusive, and democratic summit on food systems transformation has consistently been eroded. Below, we declare the reasons that pushed AFSA to officially refuse the invitation and set conditions for engaging with the UNFSS summit.

Industrial agriculture is a key driver of biodiversity loss and a significant contributor to carbon emissions. Further, as COVID-19 illustrates, there are complex interactions among deforestation, reduced biological diversity, ecosystem destruction, and human health and safety, in large part driven by globalised agricultural and food systems. Exposure to existing and emerging pathogens, as ecosystem destruction continues and essential protective barriers provided by nature are breached, are tremendous public health threats.

The inextricable connections between climate change, deforestation and industrial agriculture – a prime mechanism of agrarian extractivism and extractivist development – drive social and political instability and food insecurity on the continent, which further fuel the systemic, existential crises we face globally.

Development interventions to date have and continue to reinforce indebtedness, inequalities and social exclusion. They deepen dependency on destructive, short-sighted and short-lived fossil fuel and capital intensive projects, and global agricultural and forest value chains, which all contribute to creating conditions for extreme vulnerability to shocks, including but not limited to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Rapid and unplanned urbanisation, with the consequent shift in the labour force from largely food producing to non-food producing jobs, and a rising African middle class, is affecting rural land use and changing our food systems. The rapid erosion of Africa’s culture coincides with the degradation of our soils, which is becoming a major issue affecting the livelihoods of many, while the growing retail/supermarket sector is also destroying and displacing local food systems and local markets.

Yet Africa remains essentially a continent of smallholder food producers. Solutions will only work for Africa if they work for millions of farmers, pastoralists, fisherfolks, indigenous communities, custodians of nature, and women and youth in the food system. Hence, how Africa will feed itself in a situation of rapidly changing, catastrophic and chaotic climate change, and in a manner that heals nature and cools the planet, is one of our most urgent and pressing survival questions.

About 20% of Africans – more than 250 million people – go to bed hungry every night. At the same time, industrial ultra-processed foods and sweetened beverages have penetrated African markets – many of which are high in sugar, salt, saturated fats and preservatives, thus contributing to the spread of non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. This has also contributed to a major rise in excess weight and obesity, with the rate of overweight children under five having increased by nearly 24% since 2000. And affected populations are more vulnerable to COVID-19.

Fiscal policies and regulations, such as sugar taxes, labelling of unhealthy foods, and restricting marketing, often face strong opposition from large food companies that dominate markets. Thus, Africa faces a triple burden of hunger, malnutrition, and obesity and ill health from poor quality food. Clearly, the people of Africa are facing a multitude of intertwined crises linked to changes in our farming and food systems.

Even so, Africa has much to offer its citizens and to the world. With appropriate redirection of policies and investment, the wealth of our seed, agrobiodiversity, land, vibrant cultures and nature can contribute to solving the food crisis affecting so many of our people.

The answer lies in our collective ability to effect holistic and systemic transformation of our food systems. Such a fundamental transformation would tackle the climate crisis, lift millions out of chronic poverty, help our people defeat hunger, nurture a healthy life for all, revive vibrant cultural practices, address structural inequality, and rejuvenate the biosphere.

We are deeply concerned that the current rushed, corporate-controlled, unaccountable and opaque process for this UNFSS will not lead towards the transformation we envision of revitalised, sustainable and healthy food systems. A summit geared towards repeating the agri-business-as-usual model to solve the food and climate crisis cannot deliver on this visionary future.

The current multi-stakeholder approach and structure of the UNFSS give major influence over our food system to a few corporations and philanthro-capitalists, many of whom are part of the problems. We are profoundly concerned that the UNFSS will be used as a conduit to echo the business-as-usual, quick-technofix policy prescriptions of the agribusiness agendas.

The science is clear. Climate chaos, land-use change and erosion, and alarming biodiversity loss are the biggest existential threats to all life forms on Earth. The industrial food chain and corporate concentration around food and agriculture is the primary driver of many of the underpinning crises that humanity faces today – including health, hunger, malnutrition, deforestation, land degradation, loss of soil fertility, structural injustice and inequality.

Nothing short of a fundamental rethink of our food systems will reverse the trajectory of chaos and crises. Incremental change is no longer enough. “Agriculture at the Crossroads,” the 2009 report by the International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD), clearly indicated more than ten years ago that the future of the food supply lies in the hands of smallholder and peasant farmers. That report is still relevant today, with several of its authors having issued a follow-up earlier this year titled “Transformation of Our Food Systems: The Making of A Paradigm Shift”.

Agroecology is an alternative bottom-up paradigm that fundamentally addresses the nexus of environmental, economic, cultural and social regeneration in agriculture and overall food systems. AFSA, as part of the food sovereignty movement, stands in solidarity with peasant/family farmers, indigenous peoples, pastoralists, fishers and other citizens to exercise their fundamental human right to determine their own food and agricultural policies. AFSA stands in solidarity with thousands of farmers’ organisations and social movements worldwide to push for this holistic vision of a transition to agroecology and food sovereignty. We believe embracing agroecology is the right path to restore the damage done to our nature and cultures, cool the planet, feed the increasing population, fix the nutrition and health crisis, and build fair and just economies and thriving livelihoods. We demand that agroecology is put at the centre of the recommendations coming from the FSS.

The current UNFSS process gives little space to traditional ecological knowledge, the celebration of traditional diets and cuisine, and the social sciences, which are critical for the future of our food system. Indigenous and local community Africans have experience and knowledge relevant to the current and future food system. Any process or outcome that does not recognise this is an affront to millions of African food producers and consumers.

Therefore, AFSA must see the following conditions fulfilled before we engage with the summit:

– A transition to agroecology should be central to any outcomes of the UNFSS, based on the 13 principles of agroecology outlined in the High Level Panel of Experts for Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE) report on agroecology and how these can effectively be implemented globally in support of the Sustainable Development Goals.

– The formal FSS process should establish an additional track to focus on the transformation of corporate food systems to food sovereignty, as also demanded by the Civil Society and Indigenous Peoples’ Mechanism (CSM) of the Committee on World Food Security.

– The CSM should be given the mandate to lead proceedings of this 6th Action Track, in collaboration with relevant UN bodies and governments, and attention must be given to cross-cutting implications in the other Action Tracks.

– The traditional knowledge and practices of people, inclusive of Indigenous peoples, must be included in all processes and outcomes in a clear and demonstrable way.

– The AFSA strongly believes that the ideal and legitimate forum to host and facilitate debates as significant, complex, and crucial as rethinking global food systems should remain under the United Nation’s Committee for World Food Security (CFS).

– The FSS must commit to turning over any recommendations or outcomes to the CFS for implementation, and commit resources to strengthening the CFS and reversing its capture by corporate interests and governments.

Sincerely,

Original Source: afsafrica.org

Related posts:

UN Food Systems Summit: The Battle Over Global Food and Agriculture Governance

UN Food Systems Summit: The Battle Over Global Food and Agriculture Governance

The United Nations Food Systems Summit is a corporate food summit —not a “people’s” food summit

The United Nations Food Systems Summit is a corporate food summit —not a “people’s” food summit

Accessing information still a problem in Uganda: civil society

Accessing information still a problem in Uganda: civil society

Operations of civil society organizations will continue to be stifled until government understands their work – New Book.

Operations of civil society organizations will continue to be stifled until government understands their work – New Book.

You may like

-

UNFSS loses significance as critical issues affecting smallholder farmers are not mentioned – Criticized by Rights groups and experts

-

FAO launches solar powered irrigation systems in Kalungu

-

30 civil society organizations have written to the World Bank Group demanding to publicly disclose the Africa Energy Approach paper.

-

Court releases a tortured community land rights defender on bail

-

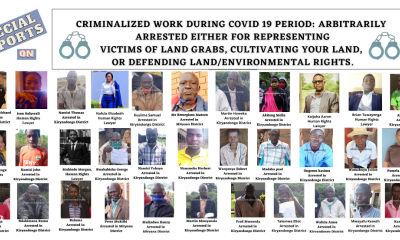

Close to 120 land rights defenders, lawyers, and PAPs leaders have been arbitrarily arrested during the COVID-19 lockdown…

-

EU to support COVID-19 vaccination strategies in Africa

NGO WORK

Violations against Kenya’s indigenous Ogiek condemned yet again by African Court

Published

3 weeks agoon

January 13, 2026

Minority Rights Group welcomes today’s decision by the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights in the case of Ogiek people v. Government of Kenya. The decision reiterates previous findings of more than a decade of unremedied violations against the indigenous Ogiek people, centred on forced evictions from their ancestral lands in the Mau forest.

The Court showed clear impatience concerning Kenya’s failure to implement two landmark rulings in favour of the indigenous Ogiek people: in a 2017 judgment, that their human rights had been violated by Kenya’s denial of access to their land, and in a 2022 judgment, which ordered Kenya to pay nearly 160 million Kenyan shillings (about 1.3 million USD) in compensation and to restitute their ancestral lands, enabling them to enjoy the human rights that have been denied them.

Despite tireless activism from the community and the historic nature of both judgments, Kenya has not implemented any part of either decision. The community remains socioeconomically marginalized as a result of their eviction and dispossession. Evictions have continued, notably in 2023 with 700 community members made homeless and their property destroyed, and in 2020 evicting about 600, destroying their homes in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Daniel Kobei, Executive Director of the Ogiek Peoples’ Development Program stated, ‘We have been at the African Court six times to fight for our rights to live on our lands as an indigenous people – rights which our government has denied us and continues to violate, compounding our plights and marginalization, despite clear orders from the African Court for our government to remedy the violations. This is the seventh time, and we were hopeful that the Court would be more strict to the government of Kenya in ensuring that a workable roadmap be followed in implementation of the two judgments.’

Kenya has repeatedly justified the eviction of Ogiek as necessary for conservation, although the forest has seen significant harm since evictions began. Many in the community see a connection between their eviction and Kenya’s participation in lucrative carbon credit schemes.

‘The Court’s decision underscores the importance of timely and full implementation of measures imposed on a state which has been found to be in breach of their internationally agreed obligations. Kenya must now repay its debt to the indigenous Ogiek by restituting their land and making reparations, among other remedies ordered by the Court’, said Samuel Ade Ndasi, African Union Advocacy and Litigation Officer at Minority Rights Group.

The decision states, ‘the court orders the respondent state to immediately take all necessary steps, be they legislative or administrative or otherwise, to remedy all the violations established in the judgment on merits.’ The court also reaffirmed that no state can invoke domestic laws to justifiy a breach of international obligations.

Both of the original judgments were historic precedents, breaking new ground on the issue of restitution and compensation for collective violations experienced by indigenous peoples and confirming the vital role of indigenous peoples in safeguarding ecosystems, that states must respect and protect their land rights, that lands appropriated from them in the name of conservation without free, prior and informed consent must be returned, and their right to be the ultimate decision makers about what happens on their lands. Today’s decision adds to this tally of precedents as it is the first decision of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights concerning the record of a state in implementing a binding decision.

The case

In October 2009, the Kenyan government, through the Kenya Forestry Service, issued a 30-day eviction notice to the Ogiek and other settlers of the Mau Forest, demanding that they leave the forest. Concerned that this was a perpetuation of the historical land injustices already suffered, and having failed to resolve these injustices through repeated national litigation and advocacy efforts, the Ogiek decided to lodge a case against their government before the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights with the assistance of Minority Rights Group, the Ogiek Peoples’ Development Program and the Centre for Minority Rights Development. The African Commission issued interim measures, which were flouted by the Government of Kenya and thereafter referred the case to the African Court based on the complementarity relationship between the African Commission and the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights and on the grounds that there was evidence of serious or massive human rights violations.

On 26 May 2017, after years of litigation, a failed attempt at amicable settlement and an oral hearing on the merits, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights rendered a merits judgment in favour of the Ogiek people. It held that the government had violated the Ogiek’s rights to communal ownership of their ancestral lands, to culture, development and use of natural resources, as well as to be free from discrimination and practise their religion or belief. On 23 June 2022, the Court rejected Kenya’s objections and set out the reparations owed for the violations established in the 2017 judgment.

Source: minorityrights.org

Related posts:

Trauma and Land Loss: New Study Focuses on Mental Health of Evicted Indigenous People

Trauma and Land Loss: New Study Focuses on Mental Health of Evicted Indigenous People

Justice Denied: East African Court of Justice Grants Tanzanian Government Impunity to Trample Human Rights of the Maasai

Justice Denied: East African Court of Justice Grants Tanzanian Government Impunity to Trample Human Rights of the Maasai

EACOP: East African Court of Justice will hear arguments on court’s jurisdiction

EACOP: East African Court of Justice will hear arguments on court’s jurisdiction

Tanzanian High Court Tramples Rights of Indigenous Maasai Pastoralists to Boost Tourism Revenues

Tanzanian High Court Tramples Rights of Indigenous Maasai Pastoralists to Boost Tourism Revenues

NGO WORK

Climate wash: The World Bank’s Fresh Offensive on Land Rights

Published

3 months agoon

November 13, 2025

Climate wash: The World Bank’s Fresh Offensive on Land Rights reveals how the Bank is appropriating climate commitments made at the Conference of the Parties (COP) to justify its multibillion-dollar initiative to “formalize” land tenure across the Global South. While the Bank claims that it is necessary “to access land for climate action,” Climatewash uncovers that its true aim is to open lands to agribusiness, mining of “transition minerals,” and false solutions like carbon credits – fueling dispossession and environmental destruction. Alongside plans to spend US$10 billion on land programs, the World Bank has also pledged to double its agribusiness investments to US$9 billion annually by 2030.

This report details how the Bank’s land programs and policy prescriptions to governments dismantle collective land tenure systems and promote individual titling and land markets as the norm, paving the way for private investment and corporate takeover. These reforms, often financed through loans taken by governments, force countries into debt while pushing a “structural transformation” that displaces smallholder farmers, undermines food sovereignty, and prioritizes industrial agriculture and extractive industries.

Drawing on a thorough analysis of World Bank programs from around the world, including case studies from Indonesia, Malawi, Madagascar, the Philippines, and Argentina, Climatewash documents how the Bank’s interventions are already displacing communities and entrenching land inequality. The report debunks the Bank’s climate action rhetoric. It details how the Bank’s efforts to consolidate land for industrial agriculture, mining, and carbon offsetting directly contradict the recommendations of the IPCC, which emphasizes the protection of lands from conversion and overexploitation and promotes practices such as agroecology as crucial climate solutions.

Read full report: Climatewash: The World Bank’s Fresh Offensive on Land Rights

Source: The Oakland Institute

Related posts:

30 civil society organizations have written to the World Bank Group demanding to publicly disclose the Africa Energy Approach paper.

30 civil society organizations have written to the World Bank Group demanding to publicly disclose the Africa Energy Approach paper.

World Bank’s new scheme to privatize land in the developing world exposed

World Bank’s new scheme to privatize land in the developing world exposed

World Bank is backing dozens of new coal projects, despite climate pledges

World Bank is backing dozens of new coal projects, despite climate pledges

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

NGO WORK

Africa’s Land Is Not Empty: New Report Debunks the Myth of “Unused Land” and Calls for a Just Future for the Continent’s Farmland

Published

3 months agoon

November 13, 2025

A new report challenges one of the most persistent and harmful myths shaping Africa’s development agenda — the idea that the continent holds vast expanses of “unused” or “underutilised” land waiting to be transformed into industrial farms or carbon markets.

Titled Land Availability and Land-Use Changes in Africa (2025), the study exposes how this colonial-era narrative continues to justify large-scale land acquisitions, displacements, and ecological destruction in the name of progress.

Drawing on extensive literature reviews, satellite data, and interviews with farmers in Zambia, Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, the report systematically dismantles five false assumptions that underpin the “land abundance” narrative:

-

That Africa has vast quantities of unused arable land available for cultivation

-

That modern technology can solve Africa’s food crisis

-

That smallholder farmers are unproductive and incapable of feeding the continent

-

That markets and higher yields automatically improve food access and nutrition

-

That industrial agriculture will generate millions of decent jobs

Each of these claims, the report finds, is deeply flawed. Much of the land labelled as “vacant” is, in reality, used for grazing, shifting cultivation, foraging, or sacred and ecological purposes. These multifunctional landscapes sustain millions of people and are far from empty.

The study also shows that Africa’s food systems are already dominated by small-scale farmers, who produce up to 80% of the continent’s food on 80% of its farmland. Rather than being inefficient, their agroecological practices are more resilient, locally adapted, and socially rooted than the industrial models promoted by external donors and corporations.

Meanwhile, the promise that industrial agriculture will lift millions out of poverty has not materialised. Mechanisation and land consolidation have displaced labour, while dependency on imported seeds and fertilisers has trapped farmers in cycles of debt and dependency.

A Continent Under Pressure

Beyond these myths, the report reveals a growing land squeeze as multiple global agendas compete for Africa’s territory: the expansion of mining for critical minerals, large-scale carbon-offset schemes, deforestation for timber and commodities, rapid urbanisation, and population growth.

Between 2010 and 2020, Africa lost more than 3.9 million hectares of forest annually — the highest deforestation rate in the world. Grasslands, vital carbon sinks and grazing ecosystems, are disappearing at similar speed.

Powerful actors — from African governments and Gulf states to Chinese investors, multinational agribusinesses, and climate-finance institutions — are driving this race for land through opaque deals that sideline local communities and ignore customary tenure rights.

A Call for a New Vision

The report calls for a radical shift away from high-tech, market-driven, land-intensive models toward people-centred, ecologically grounded alternatives. Its key policy recommendations include:

-

Promoting agroecology as a pathway for food sovereignty, ecological regeneration, and rural livelihoods.

-

Reducing pressure on land by improving agroecological productivity, cutting food waste, and prioritising equitable distribution.

-

Rejecting carbon market schemes that commodify land and displace communities.

-

Legally recognising customary land rights, particularly for women and Indigenous peoples.

-

Upholding the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) for all land-based investments.

This report makes it clear: Africa’s land is not “empty” — it is lived on, worked on, and cared for. The future of African land must not be dictated by global capital or outdated development theories, but shaped by the people who depend on it.

Download the Report

Read the full report Land Availability and Land-Use Changes in Africa (2025) to explore the evidence and policy recommendations in detail.

Related posts:

Financial Institutions from Africa have made a monumental commitment of $100 billion to Africa’s green industrialization, a decision of immense significance that has the potential to shape Africa’s future.

Financial Institutions from Africa have made a monumental commitment of $100 billion to Africa’s green industrialization, a decision of immense significance that has the potential to shape Africa’s future.

Africa adopts the Africa Climate Innovation Compact (ACIC) Declaration to drive the continent towards innovative climate solutions.

Africa adopts the Africa Climate Innovation Compact (ACIC) Declaration to drive the continent towards innovative climate solutions.

One in three people sleeps on an empty stomach – World Bank Report.

One in three people sleeps on an empty stomach – World Bank Report.

Transforming Africa’s livestock sector is key to food security-Report

Transforming Africa’s livestock sector is key to food security-Report

Why govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

Evicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Swedish pension fund drops TotalEnergies amid rising EACOP risks

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Land tenure security as an electoral issue: Museveni warns Kayunga land grabbers, reaffirms protection of sitting tenants.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoWomen environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoUganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

-

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoEvicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoWitness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days agoWhy govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry