SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Top 10 agribusiness giants: corporate concentration in food & farming in 2025

Published

5 months agoon

|

Ranking

|

Company (Headquarters)

|

Sales in 2023

(US$ millions)

|

% Global market share 19

|

|

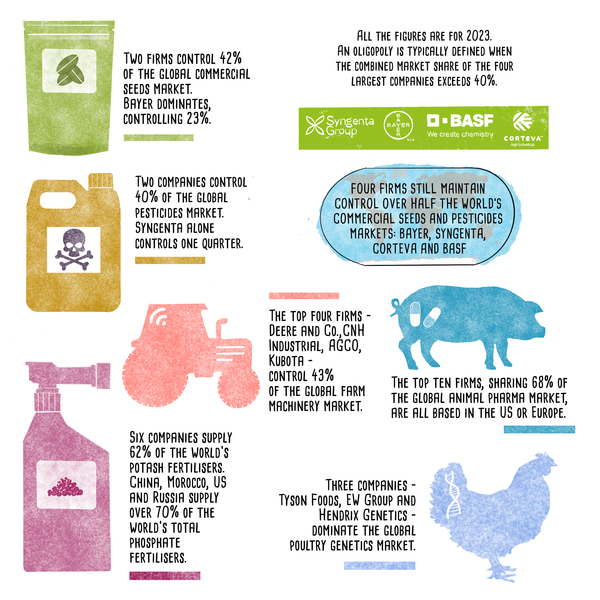

1

|

Bayer (Germany)20

|

11,613

|

23

|

|

2

|

Corteva (US)21

|

9,472

|

19

|

|

3

|

Syngenta (China/Switzerland)22

|

4,751

|

10

|

|

4

|

BASF (Germany)23

|

2,122

|

4

|

|

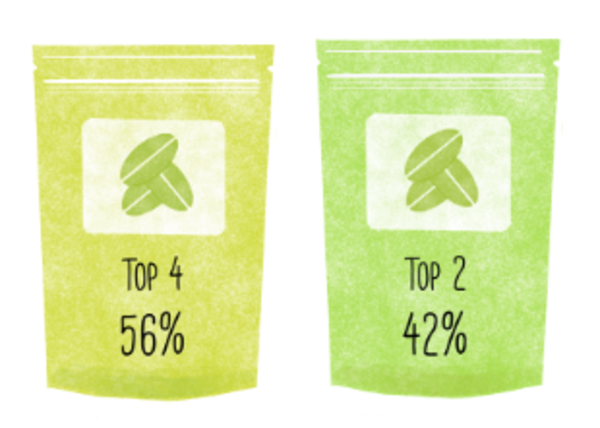

Total top 4

|

27,958

|

56

|

|

|

5

|

Vilmorin & Cie (Groupe Limagrain) (France)24

|

1,984

|

4

|

|

6

|

KWS (Germany)25

|

1,815

|

4

|

|

7

|

DLF Seeds (Denmark)26

|

838

|

2

|

|

8

|

Sakata Seeds (Japan)27

|

649

|

1

|

|

9

|

Kaneko Seeds (Japan)28

|

451

|

0.9

|

|

Total top 9

|

33,695

|

67

|

|

|

Total world market29

|

50,000

|

100%

|

|

Ranking

|

Company (Headquarters)

|

Sales in 2023

(US$ millions)

|

% Global market share

|

|

1

|

Syngenta (China/Switzerland)43

|

20,066

|

25

|

|

2

|

Bayer (Germany)44

|

11,860

|

15

|

|

3

|

BASF (Germany)45

|

8,793

|

11

|

|

4

|

Corteva (US)46

|

7,754

|

10

|

|

Total top 4

|

48,472

|

61

|

|

|

5

|

UPL (India)47

|

5,925

|

8

|

|

6

|

FMC (Germany)48

|

4,487

|

6

|

|

7

|

Sumitomo (Japan)49

|

3,824

|

5

|

|

8

|

Nufarm (Australia)50

|

2,056

|

3

|

|

9

|

Rainbow Agro (China)51

|

1,623

|

2

|

|

10

|

Jiangsu Yangnong Chemical Co., Ltd. (China)52

|

1,595

|

2

|

|

Total top 10

|

67,982

|

86

|

|

|

Total world market53

|

79,000

|

100

|

|

Ranking

|

Company (Headquarters)

|

Sales in 2023

(US$ millions)

|

% Global market share

|

|

1

|

Nutrien (Canada)72

|

15,673

|

8

|

|

2

|

The Mosaic Company (US)73

|

12,782

|

7

|

|

3

|

Yara (Norway)74

|

11,688

|

6

|

|

4

|

CF Industries Holdings, Inc, (US)75

|

6,631

|

3

|

|

Total top 4

|

46,774

|

24

|

|

|

5

|

ICL Group Ltd. (Israel)76

|

6,294

|

3

|

|

6

|

OCP (Morocco)77

|

5,967

|

3

|

|

7

|

PhosAgro (Russia)78

|

4,989

|

3

|

|

8

|

MCC EuroChem Joint Stock Company (EuroChem) (Switzerland/Russia)79

|

4,298

|

2

|

|

9

|

OCI (Netherlands)80

|

4,188

|

2

|

|

10

|

Uralkali (Russia)81

|

3,497

|

2

|

|

Total top 10

|

76,007

|

39

|

|

|

Total world market82

|

196,000

|

100

|

|

Ranking

|

Company (Headquarters)

|

Sales in 2023

(US$ millions)

|

% Global market share

|

|

1

|

Deere and Co. (US)89

|

26,790

|

15

|

|

2

|

CNH Industrial (UK/Netherlands)90

|

18,148

|

10

|

|

4

|

AGCO (US)91

|

14,412

|

8

|

|

3

|

Kubota (Japan)92

|

14,233

|

8

|

|

Total top 4

|

73,583

|

43

|

|

|

5

|

CLAAS (Germany)93

|

6,561

|

4

|

|

6

|

Mahindra and Mahindra (India)94

|

3,156

|

2

|

|

7

|

SDF Group (Italy)95

|

2,197

|

1

|

|

8

|

Kuhn Group (Switzerland)96

|

1,583

|

0.9

|

|

9

|

YTO Group (China)97

|

1,493

|

0.9

|

|

10

|

Iseki Group (Japan)98

|

1,057

|

0.6

|

|

Total top 10

|

89,629

|

52

|

|

|

Total world market99

|

173,000

|

100

|

|

Ranking

|

Company (Headquarters)

|

Sales in 2023

(US$ millions)

|

% Global market share

|

|

1

|

Zoetis (US)115

|

8,544

|

18

|

|

2

|

Merck & Co (MSD) (US)116

|

5,625

|

12

|

|

3

|

Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health (Germany)117

|

5,100

|

11

|

|

4

|

Elanco (US)118

|

4,417

|

9

|

|

Total top 4

|

23,686

|

49

|

|

|

5

|

Idexx Laboratories (US)119

|

3,474

|

7

|

|

6

|

Ceva Santé Animale (France)120

|

1,752

|

4

|

|

7

|

Virbac (France)121

|

1,348

|

3

|

|

8

|

Phibro Animal Health Corporation (US)122

|

978

|

2

|

|

9

|

Dechra (UK)123

|

917

|

2

|

|

10

|

Vetoquinol (France)124

|

572

|

1

|

|

Total top 10

|

32,727

|

68

|

|

|

Total world market125

|

48,000

|

100

|

The genetic material used in the industrial production of meat, dairy and aquaculture is supplied by a small number of relatively unknown companies that are mostly privately owned. As detailed financial data is not publicly available for most of these companies, it is difficult to determine companies’ market shares and even the value of the global market. However, it was possible to arrive at some estimates for chicken, which tops global meat production (narrowly exceeding pigs).126

The genetic material used in the industrial production of meat, dairy and aquaculture is supplied by a small number of relatively unknown companies that are mostly privately owned. As detailed financial data is not publicly available for most of these companies, it is difficult to determine companies’ market shares and even the value of the global market. However, it was possible to arrive at some estimates for chicken, which tops global meat production (narrowly exceeding pigs).126Related posts:

CORPORATE AGRIBUSINESS GIANTS SWIM IN WEALTH AS MORE POOR PEOPLE GO HUNGRY AMID THE BITING COVID PANDEMIC.

CORPORATE AGRIBUSINESS GIANTS SWIM IN WEALTH AS MORE POOR PEOPLE GO HUNGRY AMID THE BITING COVID PANDEMIC.

A corporate cartel fertilises food inflation

A corporate cartel fertilises food inflation

The United Nations Food Systems Summit is a corporate food summit —not a “people’s” food summit

The United Nations Food Systems Summit is a corporate food summit —not a “people’s” food summit

Food inflation: The math doesn’t add up without factoring in corporate power

Food inflation: The math doesn’t add up without factoring in corporate power

You may like

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

‘Food and fossil fuel production causing $5bn of environmental damage an hour’

Published

1 month agoon

December 22, 2025

UN GEO report says ending this harm key to global transformation required ‘before collapse becomes inevitable’.

Related posts:

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

New billion-dollar loans to fossil fuel companies from SEB, Nordea and Danske Bank.

New billion-dollar loans to fossil fuel companies from SEB, Nordea and Danske Bank.

Fossil fuel opponents lobby Africans for support

Fossil fuel opponents lobby Africans for support

Ecological land grab: food vs fuel vs forests

Ecological land grab: food vs fuel vs forests

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Britain, Netherlands withdraw $2.2 billion backing for Total-led Mozambique LNG

Published

2 months agoon

December 17, 2025

CONSTRUCTION HALTED IN 2021, BUT DUE TO RESTART

PROJECT CAN PROCEED WITHOUT UK, DUTCH FINANCING, TOTAL HAS SAID

CRITICISM FROM ENVIRONMENTAL, HUMAN RIGHTS GROUPS

Related posts:

Uganda, Total sign crude oil pipeline deal

Uganda, Total sign crude oil pipeline deal

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

NGOs file suit against Total over Uganda oil project

NGOs file suit against Total over Uganda oil project

Agribusiness Company with financial support from UK, US and Netherlands is dispossessing thousands.

Agribusiness Company with financial support from UK, US and Netherlands is dispossessing thousands.

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

The secretive cabal of US polluters that is rewriting the EU’s human rights and climate law

Published

2 months agoon

December 5, 2025

Leaked documents reveal how a secretive alliance of eleven large multinational enterprises has worked to tear down the EU’s flagship human rights and climate law, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). The mostly US-based coalition, which calls itself the Competitiveness Roundtable, has targeted all EU institutions, governments in Europe’s capitals, as well as the Trump administration and other non-EU governments to serve its own interests. With European lawmakers soon moving ahead to completely dilute the CSDDD at the expense of human rights and the climate, this research exposes the fragility of Europe’s democracy.

Key findings

- Leaked documents reveal how a secretive alliance of eleven companies, including Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Koch, Inc., has worked under the guise of a “Competitiveness Roundtable” to get the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) either scrapped or massively diluted.

- The companies, most of which are headquartered in the US and operate in the fossil fuel sector, aimed to “divide and conquer in the Council”, sideline “stubborn” European Commission departments, and push the European People’s Party (EPP) in the European Parliament “to side with the right-wing parties as much as possible”.

- Chevron and ExxonMobil were in charge of mobilising pressure against the CSDDD from non-EU countries. The Roundtable companies endeavoured to get the CSDDD high on the agenda of the US-EU trade negotiations and also worked on mobilising other countries against the CSDDD, in order to disguise the US influence.

- Roundtable companies paid the TEHA Group – a think tank – to write a research report and organise an event on EU competitiveness, which echoed the Roundtable’s position and cast doubt on the European Commission’s assessment of the economic impact of the CSDDD.

While Europeans were told that their governments were negotiating a landmark law to hold corporations accountable for human rights abuses and climate damage, a secretive alliance of US fossil fuel giants was working behind the scenes to destroy it. Collaborating under the innocent-sounding name ‘Competitiveness Roundtable’, eleven multinational enterprises have worked closely to eviscerate several EU sustainability laws, including the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). This Competitiveness Roundtable may be unknown, but its members are a who’s-who of polluting, mainly US, multinationals, including Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Dow. The group seems to have run rings around all branches of the EU and the Trump administration to get what they want: scrapping, or at least hugely diluting, the CSDDD.

Leaked documents obtained by SOMO reveal how, under the pretext of the now-near-magical concept of ‘competitiveness’, these companies plotted to hijack democratically adopted EU laws and strip them of all meaningful provisions, including those on climate transition plans, civil liability, and the scope of supply chains. EU officials appear not to have known who they were up against. But the documents obtained by SOMO show a high level of organisation and strategising with a clear facilitator: Teneo, a US public relations and consultancy company.

The documents indicate that many of the companies involved wanted to stay hidden from view. After all, if it were widely known that a secretive group of mostly American fossil fuel companies like Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Koch, Inc. was working as a coordinated organisation to dilute an EU climate and human rights law, that might raise questions and serious concern among the public and the policymakers they were targeting. Many of the companies in the Roundtable have never publicly spoken out against the CSDDD.

Big Oil’s ‘Competitiveness Roundtable’

The Competitiveness Roundtable is dominated by fossil fuel companies, including three Big Oil companies (ExxonMobil, Chevron, TotalEnergies) and three other companies with activities in the oil and gas sector (Koch, Inc., Honeywell, and Baker Hughes). Other members are Nyrstar (minerals and metals, a subsidiary of Trafigura Group); Dow, Inc. (chemicals); Enterprise Mobility (car rentals); and JPMorgan Chase (finance).

Teneo, the Roundtable’s coordinator, has a track record(opens in new window) of working with fossil fuel companies, including Chevron, Shell, and Trafigura, and was hired by the government of Azerbaijan to handle public relations(opens in new window) when it hosted the COP29 climate conference.

In February 2025, the European Commission published the Omnibus I proposal(opens in new window), which aims to “simplify” several EU sustainability laws, including the CSDDD. The documents obtained by SOMO reveal that the Roundtable companies, which have been meeting weekly since at least March 2025, worked on deep interventions within each of the three EU institutions to get the Omnibus I package to align exactly with their views. The EU institutions are expected to reach a final agreement on Omnibus I by the end of 2025.

The documents reveal that the Roundtable companies’ activities in the Parliament are far more significant than what is visible in the EU Transparency Register(opens in new window). Eight of the Roundtable’s lobbying meetings during the Strasbourg plenary sessions of May and June 2025, listed in the Transparency Register, show Teneo as the only attendee, thereby failing to disclose the names of other Roundtable companies that participated in these meetings. Another three meetings the Roundtable held were not found in the EU Transparency Register(opens in new window) at all.

“Divide and conquer” the Council

In the European Council, the Roundtable plotted to “divide and conquer” EU governments to get the climate article in the CSDDD deleted. In June 2025, during the final weeks of negotiations in the Council on the Omnibus I proposal, the Roundtable discussed lobbying EU government leaders to “intervene politically” to ensure its priorities were included in the Council’s negotiation mandate. Subsequently, German Chancellor Merz and French President Macron reportedly(opens in new window) personally intervened(opens in new window) in the Council’s political process, leading to a dramatic dilution(opens in new window) of the texts(opens in new window) negotiated in the months before the intervention. Several of the changes made to the texts strongly align with the Roundtable’s demands, including delaying and substantially weakening the climate obligations, scrapping EU civil liability provisions, and limiting the responsibility of companies to take responsibility for their supply chains (the ‘Tier 1’ restriction).

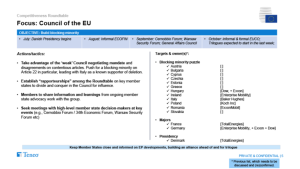

Competitiveness Roundtable meeting document, 11 July 2025.

Additionally, the documents reveal that the Roundtable is still aiming to drum up a “blocking minority” to overturn the Council’s negotiation mandate during the trilogue negotiations, which started in November 2025. By “tak[ing] advantage of the ‘weak’ Council negotiating mandate” and disagreements between EU Member States on “contentious articles”, the Competitiveness Roundtable companies hope to force the Danish Council presidency to give up on including any form of climate obligations in the CSDDD – despite EU Member States’ agreement on this in the June 2025 Council mandate(opens in new window) .

To implement the divide-and-conquer strategy, the Roundtable assigned specific companies to “establish rapporteurships” with different EU governments. TotalEnergies would target the French, Belgian, and Danish governments, and ExxonMobil would target Germany, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Romania.

Circumventing “stubborn” European Commission departments

The Roundtable also discussed working on “circumvent[ing]” two “stubborn” European Commission departments involved in the Omnibus political process, DG JUST and DG FISMA, which, in their view, were “unlikely to be willing to see our side of the story”. According to the documents, DG JUST opposed deleting the climate article and restricting the Directive’s scope to only very large enterprises. The Roundtable aimed to diminish the role of these departments by pressuring President Von der Leyen and Commissioners McGrath (DG JUST) and Albuquerque (DG FISMA) by “organising letters from Irish and German business groups” and using an event held by the European Roundtable for Industry to “target” Von der Leyen and McGrath.

Read full report: Somo.nl

Source: Somo

Related posts:

Victims of human rights violations in Uganda still waiting for redress

Victims of human rights violations in Uganda still waiting for redress

UN Human Rights Chief urges EU leaders to approve key business and human rights legislation

UN Human Rights Chief urges EU leaders to approve key business and human rights legislation

Business, UN, Govt & Civil Society urge EU to protect sustainability due diligence framework

Business, UN, Govt & Civil Society urge EU to protect sustainability due diligence framework

Development financiers fuel human rights abuses – New Report

Development financiers fuel human rights abuses – New Report

Indigenous communities in Eastern Nepal accuse the World Bank’s Linked Cable Car Project of rights violations.

Why govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

Evicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Swedish pension fund drops TotalEnergies amid rising EACOP risks

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoWomen environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoUganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

-

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoEvicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoWitness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days agoWhy govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK10 hours ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK10 hours agoIndigenous communities in Eastern Nepal accuse the World Bank’s Linked Cable Car Project of rights violations.