NGO WORK

Millions forced to choose between hunger or Covid-19

Published

5 years agoon

Related posts:

Impact of Covid-19 on small farmers

Impact of Covid-19 on small farmers

UN-Habitat policy statement on the prevention of evictions and relocations during the COVID-19 crisis

UN-Habitat policy statement on the prevention of evictions and relocations during the COVID-19 crisis

Government issues notice on land evictions amid COVID-19 lockdown

Government issues notice on land evictions amid COVID-19 lockdown

More people to go hungry as the COVID-19 pandemic hits harder

More people to go hungry as the COVID-19 pandemic hits harder

You may like

NGO WORK

US-DRC Strategic Partnership Agreement Faces Constitutional Challenge in Court

Published

10 hours agoon

February 6, 2026

Top photo: President Donald Trump participates in a trilateral signing ceremony of a peace and economic agreement with President Paul Kagame of the Republic of Rwanda and President Felix Tshisekedi of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Thursday, December 4, 2025, at the United States Peace Institute in Washington, D.C. (Official White House Photo by Daniel Torok)

- In a landmark legal action, Congolese lawyers and human rights defenders have filed a constitutional challenge against the US-DRC Strategic Partnership Agreement, signed on December 4, 2025, in Washington, DC.

- A recent report from the Oakland Institute exposed how the US-brokered “peace” deal between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is the latest US maneuver to control Congolese critical minerals.

- While US mining firms secure privileged access to vast reserves of copper, cobalt, lithium, and tantalum, promises of peace and security remain hollow as Rwanda and its proxy M23 armed group continue to occupy large swaths of mineral-rich territory in eastern DRC.

Oakland, CA – In a landmark legal action in January 2026, Congolese lawyers and human rights defenders filed a constitutional challenge against the US-DRC Strategic Partnership Agreement, signed on December 4, 2025, in Washington, DC.

Signed alongside the US-brokered “peace deal” between Rwanda and the DRC – known as the Washington Accord – the agreement grants the United States preferential access to Congolese mineral reserves and requires the DRC to amend its national laws and potentially its Constitution. The agreement further establishes a joint governance mechanism that gives Washington a direct role in overseeing the management of Congo’s mining sector.

The lawyers argue that the agreement violates the Congolese Constitution, which requires that any amendment to national laws and/or the Constitution be subject to democratic review and approval by Parliament or by popular referendum. In particular, the agreement contravenes Article 214 of the DRC’s Constitution, which governs the ratification of international agreements that alter domestic law. The petition also contends that the agreement violates Articles 9 and 217, which enshrine national sovereignty over natural resources, as well as Article 12, which guarantees equality before the law.

“By filing this case with the Constitutional Court, we are assuming our responsibility as Congolese citizens to protect the sovereignty of our country and safeguard our patrimony for future generations,” said Attorney Jean-Marie Kalonji, one of the plaintiffs.

In October 2025, the Oakland Institute released Shafted: The Scramble for Critical Minerals in the DRC, warning that US diplomatic initiatives, including the Rwanda-DRC peace deal — were being used to advance mineral extraction interests under the guise of bringing peace to the region.

“The Partnership Agreement makes it clear that these concerns were legitimate. The Congolese people have been sidelined, with an agreement focused on extraction and exploitation and a peace deal that shockingly overlooks the need for justice and for holding perpetrators accountable,” said Anuradha Mittal, Executive Director of the Oakland Institute. “While the US mining firms secure privileged access to Congo’s vast reserves of critical minerals, promises of peace and security remain hollow with Rwanda and M23 still occupying large swaths of land in mineral-rich eastern DRC,” Mittal continued.

In mid-January 2026, the DRC government took a major step towards implementing the agreement by providing Washington with a shortlist of state-owned assets — including manganese, copper, cobalt, gold and lithium projects – marked for potential US investment.

The lawyers and human rights defenders behind this case are calling for a nationwide mobilization to defend Congolese sovereignty and are urging the international community to support their legal action and uphold international law at a time when it faces an unprecedented threat.

“The Oakland Institute will continue to stand by its partners to support this mobilization and promote a Congolese-led path for peace, justice, and prosperity for the DRC instead of Trump’s hyperbole of peace and security accomplished through its mineral deal,” concluded Mittal.

Source: oaklandinstitute.org

Related posts:

Failed US-Brokered “Peace” Deal Was Never About Peace in DRC

Failed US-Brokered “Peace” Deal Was Never About Peace in DRC

Profit off Peace? Meet the Corporations Poised to Benefit from the DRC Peace Deal

Profit off Peace? Meet the Corporations Poised to Benefit from the DRC Peace Deal

Grain trader Cargill faces legal challenge in US over Brazilian soya supply chain

Grain trader Cargill faces legal challenge in US over Brazilian soya supply chain

Mps Are Likely To Defy Electorates On Age-Limit Constitutional Amendment – Survey

Mps Are Likely To Defy Electorates On Age-Limit Constitutional Amendment – Survey

NGO WORK

Violations against Kenya’s indigenous Ogiek condemned yet again by African Court

Published

3 weeks agoon

January 13, 2026

Minority Rights Group welcomes today’s decision by the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights in the case of Ogiek people v. Government of Kenya. The decision reiterates previous findings of more than a decade of unremedied violations against the indigenous Ogiek people, centred on forced evictions from their ancestral lands in the Mau forest.

The Court showed clear impatience concerning Kenya’s failure to implement two landmark rulings in favour of the indigenous Ogiek people: in a 2017 judgment, that their human rights had been violated by Kenya’s denial of access to their land, and in a 2022 judgment, which ordered Kenya to pay nearly 160 million Kenyan shillings (about 1.3 million USD) in compensation and to restitute their ancestral lands, enabling them to enjoy the human rights that have been denied them.

Despite tireless activism from the community and the historic nature of both judgments, Kenya has not implemented any part of either decision. The community remains socioeconomically marginalized as a result of their eviction and dispossession. Evictions have continued, notably in 2023 with 700 community members made homeless and their property destroyed, and in 2020 evicting about 600, destroying their homes in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Daniel Kobei, Executive Director of the Ogiek Peoples’ Development Program stated, ‘We have been at the African Court six times to fight for our rights to live on our lands as an indigenous people – rights which our government has denied us and continues to violate, compounding our plights and marginalization, despite clear orders from the African Court for our government to remedy the violations. This is the seventh time, and we were hopeful that the Court would be more strict to the government of Kenya in ensuring that a workable roadmap be followed in implementation of the two judgments.’

Kenya has repeatedly justified the eviction of Ogiek as necessary for conservation, although the forest has seen significant harm since evictions began. Many in the community see a connection between their eviction and Kenya’s participation in lucrative carbon credit schemes.

‘The Court’s decision underscores the importance of timely and full implementation of measures imposed on a state which has been found to be in breach of their internationally agreed obligations. Kenya must now repay its debt to the indigenous Ogiek by restituting their land and making reparations, among other remedies ordered by the Court’, said Samuel Ade Ndasi, African Union Advocacy and Litigation Officer at Minority Rights Group.

The decision states, ‘the court orders the respondent state to immediately take all necessary steps, be they legislative or administrative or otherwise, to remedy all the violations established in the judgment on merits.’ The court also reaffirmed that no state can invoke domestic laws to justifiy a breach of international obligations.

Both of the original judgments were historic precedents, breaking new ground on the issue of restitution and compensation for collective violations experienced by indigenous peoples and confirming the vital role of indigenous peoples in safeguarding ecosystems, that states must respect and protect their land rights, that lands appropriated from them in the name of conservation without free, prior and informed consent must be returned, and their right to be the ultimate decision makers about what happens on their lands. Today’s decision adds to this tally of precedents as it is the first decision of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights concerning the record of a state in implementing a binding decision.

The case

In October 2009, the Kenyan government, through the Kenya Forestry Service, issued a 30-day eviction notice to the Ogiek and other settlers of the Mau Forest, demanding that they leave the forest. Concerned that this was a perpetuation of the historical land injustices already suffered, and having failed to resolve these injustices through repeated national litigation and advocacy efforts, the Ogiek decided to lodge a case against their government before the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights with the assistance of Minority Rights Group, the Ogiek Peoples’ Development Program and the Centre for Minority Rights Development. The African Commission issued interim measures, which were flouted by the Government of Kenya and thereafter referred the case to the African Court based on the complementarity relationship between the African Commission and the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights and on the grounds that there was evidence of serious or massive human rights violations.

On 26 May 2017, after years of litigation, a failed attempt at amicable settlement and an oral hearing on the merits, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights rendered a merits judgment in favour of the Ogiek people. It held that the government had violated the Ogiek’s rights to communal ownership of their ancestral lands, to culture, development and use of natural resources, as well as to be free from discrimination and practise their religion or belief. On 23 June 2022, the Court rejected Kenya’s objections and set out the reparations owed for the violations established in the 2017 judgment.

Source: minorityrights.org

Related posts:

Trauma and Land Loss: New Study Focuses on Mental Health of Evicted Indigenous People

Trauma and Land Loss: New Study Focuses on Mental Health of Evicted Indigenous People

Justice Denied: East African Court of Justice Grants Tanzanian Government Impunity to Trample Human Rights of the Maasai

Justice Denied: East African Court of Justice Grants Tanzanian Government Impunity to Trample Human Rights of the Maasai

EACOP: East African Court of Justice will hear arguments on court’s jurisdiction

EACOP: East African Court of Justice will hear arguments on court’s jurisdiction

Tanzanian High Court Tramples Rights of Indigenous Maasai Pastoralists to Boost Tourism Revenues

Tanzanian High Court Tramples Rights of Indigenous Maasai Pastoralists to Boost Tourism Revenues

NGO WORK

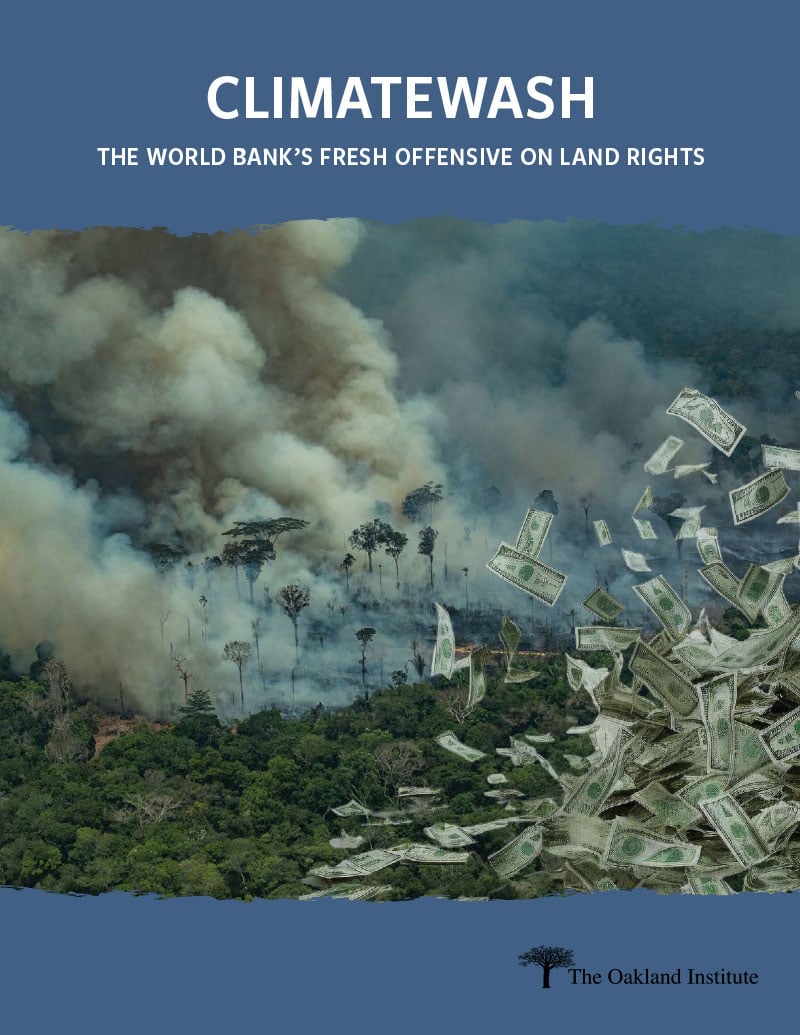

Climate wash: The World Bank’s Fresh Offensive on Land Rights

Published

3 months agoon

November 13, 2025

Climate wash: The World Bank’s Fresh Offensive on Land Rights reveals how the Bank is appropriating climate commitments made at the Conference of the Parties (COP) to justify its multibillion-dollar initiative to “formalize” land tenure across the Global South. While the Bank claims that it is necessary “to access land for climate action,” Climatewash uncovers that its true aim is to open lands to agribusiness, mining of “transition minerals,” and false solutions like carbon credits – fueling dispossession and environmental destruction. Alongside plans to spend US$10 billion on land programs, the World Bank has also pledged to double its agribusiness investments to US$9 billion annually by 2030.

This report details how the Bank’s land programs and policy prescriptions to governments dismantle collective land tenure systems and promote individual titling and land markets as the norm, paving the way for private investment and corporate takeover. These reforms, often financed through loans taken by governments, force countries into debt while pushing a “structural transformation” that displaces smallholder farmers, undermines food sovereignty, and prioritizes industrial agriculture and extractive industries.

Drawing on a thorough analysis of World Bank programs from around the world, including case studies from Indonesia, Malawi, Madagascar, the Philippines, and Argentina, Climatewash documents how the Bank’s interventions are already displacing communities and entrenching land inequality. The report debunks the Bank’s climate action rhetoric. It details how the Bank’s efforts to consolidate land for industrial agriculture, mining, and carbon offsetting directly contradict the recommendations of the IPCC, which emphasizes the protection of lands from conversion and overexploitation and promotes practices such as agroecology as crucial climate solutions.

Read full report: Climatewash: The World Bank’s Fresh Offensive on Land Rights

Source: The Oakland Institute

Related posts:

30 civil society organizations have written to the World Bank Group demanding to publicly disclose the Africa Energy Approach paper.

30 civil society organizations have written to the World Bank Group demanding to publicly disclose the Africa Energy Approach paper.

World Bank’s new scheme to privatize land in the developing world exposed

World Bank’s new scheme to privatize land in the developing world exposed

World Bank is backing dozens of new coal projects, despite climate pledges

World Bank is backing dozens of new coal projects, despite climate pledges

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

Decades of land loss and chronic poverty: Salala Rubber Plantation prioritizes profit over the well-being of local Liberian communities.

US-DRC Strategic Partnership Agreement Faces Constitutional Challenge in Court

Indigenous communities’ complaint against World Bank-linked Nepal Cable Car Project declared eligible for investigation.

The Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network Joint Radio program boosts Farmers’ knowledge of seed and food sovereignty.

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Swedish pension fund drops TotalEnergies amid rising EACOP risks

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoWomen environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoEvicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoWitness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days agoIndigenous communities in Eastern Nepal accuse the World Bank’s Linked Cable Car Project of rights violations.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK6 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK6 days agoWhy govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days agoClose to six years on, Pangero Chiefdom subjects still linger in pain after the government army’s forceful takeover of their ancestral land.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days agoThe Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network Joint Radio program boosts Farmers’ knowledge of seed and food sovereignty.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK24 hours ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK24 hours agoIndigenous communities’ complaint against World Bank-linked Nepal Cable Car Project declared eligible for investigation.