SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Manipulating Social Media to Undermine Democracy

Published

8 years agoon

Key Findings

- Online manipulation and disinformation tactics played an important role in elections in at least 18 countries over the past year, including the United States.

- Disinformation tactics contributed to a seventh consecutive year of overall decline in internet freedom, as did a rise in disruptions to mobile internet service and increases in physical and technical attacks on human rights defenders and independent media.

- A record number of governments have restricted mobile internet service for political or security reasons, often in areas populated by ethnic or religious minorities.

- For the third consecutive year, China was the world’s worst abuser of internet freedom, followed by Syria and Ethiopia.

Governments around the world have dramatically increased their efforts to manipulate information on social media over the past year. The Chinese and Russianregimes pioneered the use of surreptitious methods to distort online discussions and suppress dissent more than a decade ago, but the practice has since gone global. Such state-led interventions present a major threat to the notion of the internet as a liberating technology.

Online content manipulation contributed to a seventh consecutive year of overall decline in internet freedom, along with a rise in disruptions to mobile internet service and increases in physical and technical attacks on human rights defenders and independent media.

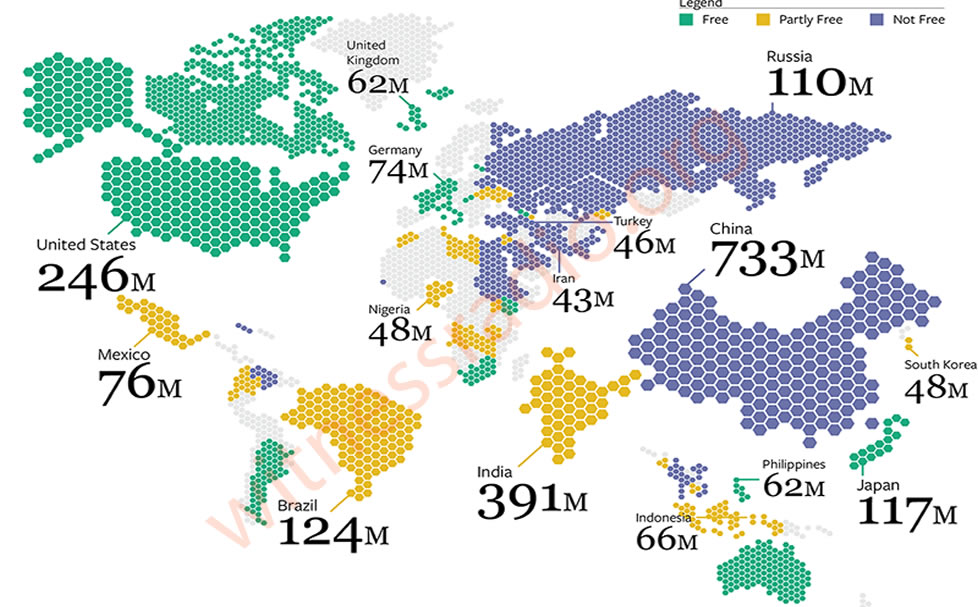

Nearly half of the 65 countries assessed in Freedom on the Net 2017 experienced declines during the coverage period, while just 13 made gains, most of them minor. Less than one-quarter of users reside in countries where the internet is designated Free, meaning there are no major obstacles to access, onerous restrictions on content, or serious violations of user rights in the form of unchecked surveillance or unjust repercussions for legitimate speech.

The use of “fake news,” automated “bot” accounts, and other manipulation methods gained particular attention in the United States. While the country’s online environment remained generally free, it was troubled by a proliferation of fabricated news articles, divisive partisan vitriol, and aggressive harassment of many journalists, both during and after the presidential election campaign.

Russia’s online efforts to influence the American election have been well documented, but the United States was hardly alone in this respect. Manipulation and disinformation tactics played an important role in elections in at least 17 other countries over the past year, damaging citizens’ ability to choose their leaders based on factual news and authentic debate. Although some governments sought to support their interests and expand their influence abroad—as with Russia’s disinformation campaigns in the United States and Europe—in most cases they used these methods inside their own borders to maintain their hold on power.

Venezuela, the Philippines, and Turkey were among 30 countries where governments were found to employ armies of “opinion shapers” to spread government views, drive particular agendas, and counter government critics on social media. The number of governments attempting to control online discussions in this manner has risen each year since Freedom House began systematically tracking the phenomenon in 2009. But over the last few years, the practice has become significantly more widespread and technically sophisticated, with bots, propaganda producers, and fake news outlets exploiting social media and search algorithms to ensure high visibility and seamless integration with trusted content.

Unlike more direct methods of censorship, such as website blocking or arrests for internet activity, online content manipulation is difficult to detect. It is also more difficult to combat, given its dispersed nature and the sheer number of people and bots employed for this purpose.

The effects of these rapidly spreading techniques on democracy and civic activism are potentially devastating. The fabrication of grassroots support for government policies on social media creates a closed loop in which the regime essentially endorses itself, leaving independent groups and ordinary citizens on the outside. And by bolstering the false perception that most citizens stand with them, authorities are able to justify crackdowns on the political opposition and advance antidemocratic changes to laws and institutions without a proper debate. Worryingly, state-sponsored manipulation on social media is often coupled with broader restrictions on the news media that prevent access to objective reporting and render societies more susceptible to disinformation.

Successfully countering content manipulation and restoring trust in social media—without undermining internet and media freedom—will take time, resources, and creativity. The first steps in this effort should include public education aimed at teaching citizens how to detect fake or misleading news and commentary. In addition, democratic societies must strengthen regulations to ensure that political advertising is at least as transparent online as it is offline. And tech companies should do their part by reexamining the algorithms behind news curation and more proactively disabling bots and fake accounts that are used for antidemocratic ends.

In the absence of a comprehensive campaign to deal with this threat, manipulation and disinformation techniques could enable modern authoritarian regimes to expand their power and influence while permanently eroding user confidence in online media and the internet as a whole.

Other key trends

Freedom on the Net 2017 identified five other trends that significantly contributed to the global decline in internet freedom over the past year:

State censors target mobile connectivity. An increasing number of governments have shut down mobile internet service for political or security reasons. Half of all internet shutdowns in the past year were specific to mobile connectivity, with most others affecting mobile and fixed-line service simultaneously. Many of the mobile shutdowns occurred in areas populated by minority ethnic or religious groups that have challenged the authority of the central government or sought greater rights, such as Tibetan areas in China and Oromo areas in Ethiopia. The actions cut off internet access for already marginalized people who depend on it for communication, commerce, and education.

More governments restrict live video. As live video streaming gained popularity over the last two years with the emergence of platforms like Facebook Live and Snapchat’s Live Stories, some governments have attempted to restrict it, particularly during political protests, by blocking live-streaming applications and arresting people who are trying to broadcast abuse. Considering that citizen journalists most often stream political protests on their mobile phones, governments in countries like Belarus have at times disrupted mobile connectivity specifically to prevent live-streamed images from reaching mass audiences. Officials often justified their restrictions by noting that live streaming can be misused to broadcast nudity or violence, but blanket bans on these tools prevent citizens from using them for any purpose.

Technical attacks against news outlets, opposition, and rights defenders on the rise. Cyberattacks became more common due in part to the increased availability of relevant technology, which is sold in a weakly regulated market, and in part to inadequate security practices among many of the targeted groups or individuals. The relatively low cost of cyberattack tools has enabled not only central governments, but also local government officials and law enforcement agencies to obtain and employ them against their perceived foes, including those who expose corruption and abuse. Independent blogs and news websites are increasingly being taken down through distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, activists’ social media accounts are being disabled or hijacked, and opposition politicians and human rights defenders are being subjected to surveillance through the illegal hacking of their phones and computers. In many cases, such as in Bahrain, Azerbaijan, Mexico, and China, independent forensic analysts have concluded that the government was behind these attacks.

New restrictions on virtual private networks (VPNs). Although VPNs are used for diverse functions—including by companies to enable employees to access corporate files remotely and securely—they are often employed in authoritarian countries as a means of bypassing internet censorship and accessing websites that are otherwise blocked. This has made VPNs a target for government censors, with 14 countries now restricting the connections in some form and with six countries introducing new restrictions over the past year. The Chinese government, for example, issued regulations that required registration of “approved VPNs,” which are presumably more compliant with government requests, and has moved to block some of the unregistered services.

Physical attacks against netizens and online journalists expand dramatically. The number of countries that featured physical reprisals for online speech increased by 50 percent over the past year—from 20 to 30 of the countries assessed. Online journalists and bloggers who wrote on sensitive topics and individuals who criticized or mocked prevailing religious beliefs were the most frequent targets. In eight countries, people were murdered for their online expression. In Jordan, for example, a Christian cartoonist was shot dead after publishing an online cartoon that lampooned Islamist militants’ vision of heaven, while in Myanmar, an investigative journalist was murdered after posting notes on Facebook that alleged corruption.

Several of the practices described above are clearly outside the bounds of the law, signaling a departure from the trend observed in previous years, when governments rushed to pass new laws that regulated internet activity and codified censorship tactics. For instance, spreading fake news and smearing individuals’ public image are often criminal offenses in countries where the government employs those tactics against its critics. Similarly, in a number of countries where the government is apparently behind cyberattacks affecting the human rights community, newly passed cybersecurity laws actually prohibit such activity. Even in cases of mobile shutdowns, most countries do not have specific laws authorizing the disruptions. It appears that in many countries, the internet regulations imposed in recent years apply only to civilians in practice, and government officials are able to disregard them with impunity.

Internet Freedom vs. Internet Penetration vs. GDP

Tracking the global decline

Freedom on the Net is a comprehensive study of internet freedom in 65 countries around the globe, covering 87 percent of the world’s internet users. It tracks improvements and declines in government policies and practices each year. The countries included in the study are selected to represent diverse geographical regions and regime types. This report, the seventh in its series, focuses on developments that occurred between June 2016 and May 2017, although some more recent events are included in individual country narratives. More than 70 researchers, nearly all based in the countries they analyze, contributed to the project by examining laws and practices relevant to the internet, testing the accessibility of select websites and services, and interviewing a wide range of sources.

Of the 65 countries assessed, 32 have been on an overall decline since June 2016. The biggest declines took place in Ukraine, Egypt, and Turkey. In Ukraine, the government blocked major Russian-owned platforms, including the country’s most widely used social network (VKontakte) and search engine (Yandex), on national security grounds. Meanwhile, violent reprisals for online activity escalated in the country, with one prominent online journalist killed in a car bombing. In Egypt, the authorities blocked over 100 websites, including that of the Qatar-based news network Al-Jazeera, the independent news site Mada Masr, and the blogging platform Medium. Social media users received lengthy prison sentences for a range of alleged offenses, including insulting the country’s president. And in Turkey, thousands of smartphone owners were arrested simply for having downloaded the encrypted communication app ByLock, which was available publicly through Apple and Google app stores, amid allegations that the app was used by those involved in the failed July 2016 coup attempt.

China was the worst abuser of internet freedom for the third consecutive year. The Chinese government’s crackdown intensified in advance of the Communist Party’s 19th National Congress in October 2017, which ushered in Xi Jinping’s second five-year term as general secretary. The year’s restrictions included official orders to delete all online references to a newly discovered species of beetle named after Xi, which the censors reportedly found offensive given the beetle’s predatory nature. Meanwhile, the authorities further eroded user privacy through a new cybersecurity law that strengthened internet companies’ obligation to register users under their real names and assist security agencies with investigations. Domestic companies are implementing the measures as part of a gradual move toward a unified “social credit” system—assigning people numerical scores based on their internet usage patterns, much like a financial credit score—that could ultimately make access to government and financial services dependent on one’s online behavior. The cybersecurity law also requires foreign companies to store data on Chinese users within China by 2018, and many—including Uber, Evernote, LinkedIn, Apple, and AirBnb—have started to comply.

Government critics received sentences of up to 11 years in prison for publishing articles on overseas websites. While such penalties are documented year after year, the July 2017 death of democracy advocate Liu Xiaobo from liver cancer while in custody was a stark reminder of the immense personal toll they may take on those incarcerated. Liu, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, had been in prison since a prodemocracy manifesto he coauthored was circulated online in 2009. News of his passing sparked a new wave of support—and censorship.

The internet freedom status of Venezuela and Armenia was downgraded. Venezuela went from Partly Free to Not Free amid a broader crackdown on political rights and civil liberties following President Nicolás Maduro’s May 2016 declaration of a “state of exception and economic emergency,” which was renewed in May 2017. The government blocked a handful of sites that provided live coverage of antigovernment protests, claiming the sites were “instigating war.” Armed gangs physically attacked citizen and online journalists who tried to document antigovernment protests, while the political opposition and independent outlets experienced an unprecedented wave of cyberattacks, effectively taking their sites offline for periods of time and disabling their accounts. In Armenia, which dropped from Free to Partly Free, the police attacked and obstructed journalists and netizens who were trying to live stream antigovernment protests. Thousands of people demonstrated in response to the police’s mishandling of a hostage situation, during which officials temporarily restricted access to Facebook.

The United States also experienced an internet freedom decline. While the online environment in the United States remained vibrant and diverse, the prevalence of disinformation and hyperpartisan content had a significant impact. Proliferation of “fake news”—particularly on social media—peaked in the run-up to the November 2016 presidential election, but it continues to be a concern. Journalists who challenge Donald Trump’s positions have faced egregious online harassment.

Among other noteworthy developments, after Trump assumed office as president in January 2017, U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents in March asked Twitter to reveal the owner of an account that objected to Trump’s immigration policy, and backed off only after the company fought the request in court. Even more worrying was a government request in July 2017 to compel internet hosting company DreamHost to hand over all the internet protocol addresses of users who visited disruptj20.org, a website that helped coordinate Trump inauguration protests; this request was narrowed only after a legal challenge from DreamHost. Meanwhile, the new chairman of the Federal Communications Commission announced a plan in April to roll back net neutrality protections adopted in 2015.

Only 13 countries earned an improvement in their internet freedom score. In most cases, the gains were limited and did not reflect a broad shift in policy. In Libya, for example, several news websites were unblocked, and unlike in previous years, no users were imprisoned for their online activity. In Bangladesh, there was no repetition of the government’s temporary 2015 blocking of popular apps like Facebook, WhatsApp, and Viber amid security concerns following the confirmation of death sentences against two Islamist leaders. And Uzbekistan, one of the most restrictive states assessed, improved slightly after the introduction of a new e-government platform designed to channel public grievances, which prompted greater citizen engagement.

Freedom on the Net 2017 Overall Scores

Scores: 0 = Most Free, 100 = Least Free

Major Developments

Bots and fake news add a new sophistication to manipulation online

Repressive regimes have long sought to control the flow of information within their territories, a task rendered more difficult by the advent of the internet. When punitive laws, online censorship, and other restrictive tactics prove inadequate and comprehensive crackdowns are untenable, more governments are mass producing their own content to distort the digital landscape in their favor. Freedom House first tracked the use of paid progovernment commentators in 2009, but more governments are now employing an array of sophisticated manipulation tactics, which often serve to reinforce one another. Authoritarians have effectively taken up the same tools that many grassroots democratic activists used to disrupt the state media narrative, and repurposed them to advance an antidemocratic agenda.

The Russian government’s attempted use of bots and fake news to sway elections in the United States and Western Europe has brought new attention to the issue of content manipulation. But in many countries, these tactics are used not by foreign powers, but by incumbent governments and political parties seeking to perpetuate their rule.

Progovernment commentators feign grassroots support

Progovernment commentators were found in 30 of the 65 countries surveyed in this study, up from 23 in the 2016 edition and a new high. In these countries, there are credible reports that the government employs staff or pays contractors to manipulate online discussions without making the sponsored nature of the content explicit. The evidence has been collected largely through investigative reporting, leaked government documents, and academic research. The manipulation has three principal aims: (1) feigning grassroots support for the government (also known as “astroturfing”), (2) smearing government opponents, and (3) moving online conversations away from controversial topics. The progovernment commentators tasked with achieving these goals come in many forms.

In the most repressive countries, members of the government bureaucracy or security forces are directly employed to manipulate political conversations. For example, Sudan ’s so-called cyber jihadists—a unit within the National Intelligence and Security Service—created fake accounts to infiltrate popular groups on Facebook and WhatsApp, fabricate support for government policies, and denounce critical journalists. A government propagandist in Vietnam has also acknowledged operating a team of hundreds of “public opinion shapers” to monitor and direct online discussions on everything from foreign policy to land rights.

In other cases, online manipulation is outsourced to the ruling party apparatus, political consultancies, and public relations firms. Investigative reporting has exposed the role of the Internet Research Agency, a Russian “troll farm” reportedly financed by a businessman with close ties to President Vladimir Putin. In the Philippines, news reports citing former members of a “keyboard army” said they could earn $10 per day operating fake social media accounts that supported Rodrigo Duterte or attacked his detractors in the run-up to his May 2016 election as president; many have remained active under his administration, amplifying the impression of widespread support for his brutal crackdown on the drug trade. In Turkey, numerous reports have referred to an organization of “AK Troller,” or “White Trolls,” named after the ruling Justice and Development Party, whose Turkish acronym AK also means “white” or “clean.” Some 6,000 people have allegedly been enlisted by the party to manipulate discussions, drive particular agendas, and counter government opponents on social media. Journalists and scholars who are critical of the government have faced orchestrated harassment on Twitter, often by dozens or even hundreds of users.

Over the years, governments have found new methods of crowdsourcing manipulation to achieve a greater impact and avoid direct responsibility. As a result, it can be hard to distinguish propaganda from actual grassroots nationalism, even for seasoned observers. For example, the government in China has long enlisted state employees to shape online discussions, but they are now just a small component of a larger ecosystem that incorporates volunteers from the ruling party’s youth apparatus as well as ordinary citizens known as “ziganwu.” In official documents, the Communist Youth League described “online civilization volunteers” as people using “keyboards as weapons” to “defend the online homeland” in the ongoing “internet war.”

In at least eight countries, politicians encourage or even incentivize followers to report “unpatriotic content,” harass “enemies of the state,” or flood social media with comments hailing government policies—often working hand-in-hand with paid commentators and propagandists. A senior police official in Thailand invited citizens to serve as the eyes and ears of the state after the 2014 military coup, awarding $15 to those who report users for opposing the military government. Separately, over 100,000 students have been trained as “cyber scouts” to monitor and report online behavior deemed to threaten national security, while supporters of the regime wage witch hunts on Facebook, identifying and reporting other users who break strict laws against criticizing the monarchy. In Ecuador, then president Rafael Correa launched a website that sent supporters a notification whenever a social media user criticized the government, allowing progovernment commentators to collectively target political dissidents.

Bots drown out activists with nonsense and hate speech

In addition to human commentators, both state and nonstate actors are increasingly creating automated accounts on social media to manipulate online discussions. In at least 20 countries, characteristic patterns of online activity suggested the coordinated use of such “bots” to influence political discourse. Thousands of fake names and profiles can be deployed with the click of a mouse, algorithmically programmed to focus on certain critical voices or keywords. They are capable of drowning out dissent and disrupting attempts to mobilize collective action online.

According to estimates by cloud services provider Imperva Incapsula, bots made up 51.2 percent of all web traffic in 2016. Many of them conduct automated tasks for commercial purposes. For example, bots now play a vital role in monitoring the health of websites, ordering products online, and pushing new content from desktop websites to mobile apps. These “good bots” are identifiable and operated by many of the largest technology companies, including Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft. Malicious bots, however, are unidentifiable by design and have made up the majority of bot activity since 2013. They can be used for hacking, spamming, stealing content, and impersonating humans in public discussions.

Studies have demonstrated the difficulty of detecting bots through any single criterion. On Twitter, bot accounts characteristically tweet frequently, retweet one another, and disseminate links to external content more often than human-operated accounts. Bots are also used in a transnational industry of artificial “likes” and followers. For example, a review of President Donald Trump’s Twitter followers by Newsweek in May determined that only 51 percent of his 30 million followers were real.

In some cases, malicious bots have been deployed in governments’ information wars against foreign adversaries and domestic opponents.

In Mexico, an estimated 75,000 automated accounts known colloquially as Peñabots have been employed to overwhelm political opposition on Twitter. When a new hashtag emerges to raise awareness about a protest or corruption scandal, government backers employ two methods to game the system in favor of President Enrique Peña Nieto. In one method, the bots promote alternative hashtags that push the originals off the top-10 list. In another method known as “hashtag poisoning,” the bots flood the antigovernment hashtags with irrelevant posts in order to bury any useful information. Hashtag poisoning can have real-world consequences: Unable to access maps of police activity and safe exit routes, many peaceful protesters in Mexico were unable to flee danger zones and instead faced excessive force by the police.

Bots can also be used to smear regime opponents and promote sectarianism. In Bahrain, for example, where much of the Shiite majority has demanded political reform from the repressive Sunni monarchy, a researcher found that just over half of all tweets on the hashtag #Bahrain in a given time period consisted of anti-Shiite hate speech. Tweets featuring nearly identical language accused a prominent Shiite cleric of inciting violence against state security forces. This bot army has been mobilized in online conversations about Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Iran, always denigrating Shiite Muslims.

Hijacked accounts spread disinformation

In at least nine countries, hackers with suspected links to the government or ruling party hijacked social media accounts and news sites in order to spread disinformation. In the Middle East, the alleged hacking of a Qatari state news site to post pro-Iranian statements attributed to high-level Qatari officials sparked an international incident. Although Qatar denied the veracity of the stories, a regional coalition led bySaudi Arabia responded with a blockade that included the obstruction of dozens of Qatari-linked news sites. Amid the hysteria, authorities in Egypt also blocked the websites of dozens of independent news outlets and human rights organizations.

While Qatar’s hacking allegations have yet to be independently confirmed, it would not be an isolated case. On the eve of Belarus’s “Freedom Day” demonstration, an opposition leader and protest organizer’s Facebook account was hacked in order to post fake comments discouraging people from attending the event. In Turkey, hackers have taken over the accounts of prominent journalists and activists so as to publish fake apologies in which the victims express regret for criticizing the government. Access Now reported that in Venezuela, Myanmar, and Bahrain, hackers spread disinformation through “DoubleSwitch” attacks. After gaining access to a verified account, changing the recovery email address, and altering the account handle, the hackers created a new account under the victim’s name and original handle, then disseminated content from both accounts.

These incidents underline the role of poor cybersecurity in online manipulation. Many hackers exploit weaknesses in SMS-based two-factor authentication for social media accounts, particularly if the victim resides in a country where state-sponsored hackers may collude with state-run telecommunications companies. International tech firms have made improvements in monitoring for state-sponsored attacks, although the repeated theft or leaking of customers’ personal data by cybercriminals can provide progovernment hackers with much of the confidential material they need to clear even the strongest identification hurdles.

Fake news proliferates in a new media environment

The “democratization” of content production and the centralization of online distribution channels like Twitter and Facebook has shaken up the media industry, and one unintended consequence has been the proliferation of fake news—intentionally false information that has been engineered to resemble legitimate news and garner maximum attention. Fake news has existed since the dawn of the printing press. However, its purveyors have recently developed sophisticated ways—such as gaming the algorithms of social media and search engines—to reach large audiences and mislead news consumers.

Social media are increasingly used as a primary source of news and information, but users’ inability to distinguish between genuine news and lucrative or politically motivated frauds seriously reduces their value and utility. Although there is little information publicly available regarding the algorithms of Facebook, Google, Twitter, and other information gatekeepers, they have tended to promote viral or provocative articles that generate clicks, regardless of the veracity of their content. Just as upstart media organizations like BuzzFeed tailored the titles of real articles to suit Facebook’s NewsFeed, enterprising Macedonian teenagers crafted click-bait headlines for fake articles in advance of the November 2016 U.S. elections, profiting immensely from Google Ads placed on their sites. Such illegitimate news content appeared on social media platforms alongside articles from legitimate outlets, with no obvious distinction between the two.

Freedom House documented prominent examples of fake news around elections or referendums in at least 16 of the 65 countries assessed. Government agents in Venezuela regularly used manipulated footage to disseminate lies about opposition protesters on social media, creating confusion and undermining the credibility of the opposition movement ahead of elections. In Kenya, users readily shared fake news articles and videos bearing the logos of generally trusted outlets such as CNN, the BBC, and NTV Kenya on social media and messaging apps in advance of the August 2017 election.

While fake news sites are not new, they are being used with increasing sophistication for political purposes. Progovernment actors in Iran have long created sites like persianbbc.ir to mimic the look of the authentic bbcpersian.com, filling them with conspiracy theories and anti-Western propaganda. More recently, Iranian hacker groups have established websites with names like BritishNews and AssadCrimes as part of more elaborate social-engineering schemes. The latter contained articles lifted from a Syrian opposition blog and was falsely registered under the name of a prominent opposition activist. Hackers created email addresses and social media profiles linking to the fake publications in order to communicate with government opponents and human rights defenders and map out their social networks. Once trust was established, the hackers targeted victims with so-called remote access trojan (RAT) programs and gained access to their devices.

Progovernment news and propaganda

The line between real news and propaganda is often difficult to discern, particularly in hyperpartisan environments where each side accuses the other of distorting facts. Societies with strong respect for media freedom and free speech allow citizens to consult a diverse range of news sources and develop an informed understanding of events. However, in over half of the countries included in the report, the online media landscape is warped by frequent bribes, politicized editorial directives, or ownership takeovers by government-affiliated entities and individuals—all of which Freedom House has observed for many years in such countries’ print and broadcast sectors. The result is often an environment in which all major news outlets toe the government line.

In Azerbaijan, media pluralism has been undermined by restrictions on foreign funding that leave media outlets dependent on the state-controlled domestic advertising market. In Hungary, <turkey< strong=””>, and Russia, the government or oligarchs with strong links to the ruling party have purchased numerous online outlets, dismissed critical journalists, and quickly altered the sites’ editorial stance.

Some of the most prominent purveyors of state propaganda are governments that claim to be combating disinformation. In Cuba, where laws criminalize the dissemination of “enemy propaganda” and “unauthorized news,” online media have long been dominated by state-run outlets and progovernment bloggers who defend the actions of the leadership and its foreign allies. The constitution prohibits private ownership of media outlets and allows freedom of speech and freedom of the press only if they “conform to the aims of a socialist society.”

But in few places was the hypocritical link between state propaganda and legal restrictions on the media stronger than in Russia. Bloggers who obtain more than 3,000 daily visitors must register their personal details with the Russian government and abide by the law regulating mass media. Search engines and news aggregators were banned from including stories from unregistered outlets under a new law that took effect in January 2017. Foreign social media platforms have been pressured to move their servers within the country’s borders to facilitate state control, while key local platforms have been purchased by Kremlin allies.

Diverse responses to manipulation

In a troubling trend, governments in at least 14 countries actually restricted internet freedom in a bid to address various forms of content manipulation. In Ukraine, one of the first countries to experience Russia’s modern information warfare, Russian agents have operated fake Ukrainian news sites and flooded social media with invented reports on Crimea’s desire to be part of Russia, Ukrainian citizens’ rejection of the European Union, and other stories that promote the Kremlin’s narrative. In response, Ukrainian authorities have blocked a number of Russia-based social media platforms and search engines, joining a list of countries including China and Iran that have ordered extended bans on prominent social media services. The affected sites—Odnoklassniki, VKontakte, Yandex, and Mail.ru—were widely used by Ukrainians.

Several democratic countries are debating the appropriate response to the fake news phenomenon and, more broadly, the responsibility of intermediaries such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter to remove fraudulent or illegal content. Germany’s Social Media Enforcement Law, passed in June 2017, obliges companies to take down content that is flagged as illegal in a process that lacks judicial oversight. The law is deeply problematic and may create incentives for social media companies to preemptively delete any controversial content, including legitimate speech, in order to avoid fines of up to €50 million. With similar moves proposed in Italy and the Philippines, the German law may set an unfortunate example for both democratic and repressive governments on how to use legal pressure to ensure that companies comply with local demands for censorship.

More broadly, it will take considerable time, resources, and creativity to successfully combat content manipulation and restore trust in social media in a manner that does not undermine internet and media freedom. Already, increased public awareness has resulted in pressure on internet companies to redouble their efforts to remove automated accounts and flag fake or misleading news posts. Some 30,000 fake accounts were removed from Facebook ahead of the 2017 French elections, while Google altered its search rankings to promote trusted news outlets over dubious ones. Twitter also announced that it will do more to detect and suspend accounts used for the primary purpose of manipulating trending topics.

But social media platforms and search engines are only part of the puzzle. Organizations such as First Draft News and Bellingcat provide professional and citizen journalists alike with the tools needed to verify user-generated content, monitor manipulation campaigns, and debunk fake news. More must be done to provide local, tailored solutions to the problem of manipulation in different countries. This is particularly the case in settings where many people get their news from messaging platforms like WhatsApp and Telegram, which makes false information even more difficult to detect.

State censors target mobile connectivity

Network shutdowns—defined by Freedom House as intentional restrictions on connectivity for fixed-line internet networks, mobile data networks, or both—have occurred in a growing number of countries in recent years. In the 2017 edition, 19 out of 65 countries tracked by Freedom on the Nethad at least one network shutdown during the coverage period, up from 13 countries in the 2016 edition and 7 countries in the 2015 edition. Over the past year, authorities have often invoked national security and public safety to shut down communication networks, but in reality the pretexts have ranged from armed conflict and social unrest to peaceful protests, elections, and online “rumors” that could supposedly cause internal strife.

Authorities are increasingly targeting mobile service as opposed to fixed-line networks. During this report’s coverage period, mobile-only disruptions were reported in nine out of of 19 countries with reported shutdowns, while incidents in most remaining countries affected mobile and fixed-line networks simultaneously. Shutdowns targeting fixed-line internet only were documented in just two countries, and they were attributed to authorities conducting tests of their ability to impose broader shutdowns in the future.

There are several reasons why governments may be singling out mobile connectivity. For one, mobile internet use has become the predominant mode of internet access around the world, with global traffic from mobile networks surpassing fixed-line internet traffic for the first time in late 2016. In many developing countries, the majority of internet users access the web from their mobile devices due to the increasing affordability of mobile data subscriptions and devices compared with fixed-line subscriptions. In addition, fixed-line and Wi-Fi connections are tied to specific locations or infrastructure, while mobile connections enable users to connect wherever they can get a signal, giving a mobile shutdown greater impact.

Mobile networks are also being targeted due to the ease with which people can use mobile devices to communicate and organize on the move and in real time, a feature that is appealing to peaceful protesters and violent terrorists alike. Targeted mobile shutdowns also leave fixed-line networks accessible for businesses and government institutions, which can help blunt the negative economic impact of the restrictions.

Mobile shutdowns cut off marginalized communities

In a troubling new trend, the authorities in at least 10 countries deliberately disrupted mobile connectivity in specific regions, often targeting persecuted ethnic and religious groups. In China, for example, Tibetan and Uighur communities have faced regular mobile shutdowns for years, most recently in a Tibetan area of Sichuan Province where officials sought to prevent the spread of news about a Tibetan monk’s self-immolation to protest government repression. In Ethiopia, the government shut down mobile networks for nearly two months as part of a state of emergency declared in October 2016 amid large-scale antigovernment demonstrations by the disenfranchised Oromo and Amhara populations.

For many of the communities affected by such localized shutdowns, mobile service is the only affordable or available option for internet connectivity due to underdeveloped fixed-line infrastructure in remote regions. Consequently, the shutdowns can effectively silence a specific community, not only minimizing their ability to call attention to their political and social grievances, but also diminishing their economic development and educational opportunities.

In addition to their growing frequency, the shutdowns initiated over the past year have been longer in duration, with at least three countries— Lebanon, Bahrain, and Pakistan—experiencing regional shutdowns that lasted more than one year. In Lebanon, 160,000 residents of the northeastern border town of Arsal, many of whom are Syrian refugees, have been completely cut off from mobile internet for over two years as a security measure amid frequent clashes between the military and extremist militants. Since June 2016, Bahraini authorities have required telecom companies to disable mobile and fixed-line connections during nightly curfews in the town of Duraz, where supporters of a prominent Shiite cleric were protesting persecution by the Sunni monarchy.

Service disruptions coincide with elections, special events

Mobile shutdowns have also been deployed to stifle opposition groups during contentious elections periods. During Zambia’s August 2016 presidential election, mobile broadband networks were reportedly disrupted for up to 72 hours in opposition-held regions following protests by opposition supporters who accused the electoral commission of fraud. Similarly in the Gambia, networks were shut down on the eve of a presidential election in December 2016, though in a surprise victory for democracy, the tactic failed to secure the reelection of authoritarian incumbent Yahya Jammeh, who had been in power for nearly 22 years.

Some governments restricted mobile communications during large events out of concern that they could be used to harm public security. In the past year, the authorities in at least three cities in the Philippines directed telecom providers to shut down mobile networks during public festivals and parades; Philippine officials had previously restricted mobile connectivity during the pope’s visit in 2015. Though the shutdown directives were all narrow in scope and duration and communicated to the public, the repeated events have helped normalize shutdowns as a legitimate government measure, despite their disproportionate nature and profound effect on freedom of expression.

App restrictions and price increases curb mobile access

Indirect methods of control over mobile connectivity typically receive less attention than network shutdowns, but they can have the same effect of disrupting essential communications. In keeping with a trend highlighted in Freedom on the Net 2016, popular mobile-specific apps were repeatedly singled out for restrictions during the past year. WhatsApp remained the most targeted communication tool, experiencing disruptions in 12 of the 65 countries assessed. In Turkey, for example, the authorities regularly throttled traffic for WhatsApp to render it virtually inaccessible during politically charged events, while officials in Zimbabwe blocked it for several hours during large antigovernment protests.

Artificial regulation of mobile data prices was also used to indirectly restrict access. After WhatsApp was unblocked in Zimbabwe, the government reportedly hiked the cost of mobile data plans by 500 percent to limit further civic organizing. When mobile networks are not shut down altogether in India‘s restive state of Jammu and Kashmir, the authorities often suspend pay-as-you-go mobile data plans, which most acutely affects low-income residents who cannot afford subscriptions.

Governments restrict live video, especially during protests

Internet users faced restrictions or attacks for streaming live video in at least nine countries. Live broadcasting tools and channels were subject to blocking, and several people were detained to halt real-time coverage of antigovernment demonstrations.

Streaming video in real time has become increasingly popular since the launch of a now-defunct mobile app, Meerkat, in early 2015. Many apps have since added live-streaming features, and deliver content to large global networks. The ability to stream live content directly from a mobile device without the need for elaborate equipment or a distribution strategy has made the technology more accessible. Dedicated news outlets and other content producers also continue to stream live content from their own websites, and some are now doing so in conjunction with apps and social media platforms. Often this allows them to bypass regulations specific to traditional broadcasters, and to reach new audiences.

People stream all sorts of things, from cultural events to everyday interactions. But live video is an important tool for documenting state abuse. In Armenia, digital journalist Davit Harutyunyan reported that police officers assaulted him and broke his equipment to stop him from sharing live footage of police attacking other journalists as they covered antigovernment demonstrations. Even in democracies such as the United States, live-streaming tools have become critical to social justice causes. In one case, live video broadcast on social media by the girlfriend of black motorist Philando Castile after he was fatally shot by police in Minnesota in July 2016 helped bring the incident to nationwide prominence.

Journalists have embraced live streaming, and it has developed into an accessible alternative to broadcast television channels, especially in countries whose traditional media outlets do not tell the full story. Before May 2017 elections in Iran, reformist figures who supported President Hassan Rouhani’s quest for a second term used Instagram Live to cover campaign events and nightly programs despite being sidelined by the state broadcaster IRIB, which has a virtual monopoly on traditional broadcast media. In a testament to the success of this strategy, the protocol that allows Instagram users to stream video was briefly blocked, and when it became accessible again, the hard-line candidate Ebrahim Raisi embraced the platform as well.

Government censors have had to adapt to the trend. In Bahrain, the information ministry banned news websites from streaming live video altogether in July 2016. Others, like Iran when it blocked Instagram, used more ad hoc methods to disrupt live streaming when it was already in progress. Venezuelan regulators ordered service providers to block three websites that broadcast live as tens of thousands of protesters marched against President Maduro in April 2017. In June, live coverage of anticorruption protests in Russia was interrupted when the electricity supply to the office of opposition leader Aleksey Navalny was intentionally cut off, leaving his YouTube channel Navalny Live without light and sound.

The public use of smartphones to document events in real time turned ordinary internet users into citizen journalists—and easy targets for law enforcement officials. At least two video bloggers were arrested and a third was fined for broadcasting antigovernment Freedom Day protests in Belarus; local colleagues observed that they lack the institutional support and legal protections of their professional counterparts. Yet a Belarusian animal rights worker was fined in a separate case because a court found that her live video from a rescue shelter violated a law governing mass media broadcasts.

Live streaming has earned notoriety for enabling users to broadcast nudity, drug use, or even violence. Some countries restricted real-time broadcasts to curb obscenity, but the effects extended to journalism and digital activism. Singaporean streaming app Bigo Live was shuttered for a month in Indonesia until it brokered a deal with the government to limit streaming activity that violates Indonesia’s broad bans on obscene or otherwise “negative” content. And in China, police in southern Guangdong Province shut down hundreds of live-streaming channels during a purge of pornography and other illegal content—a category that includes banned news and commentary.

Cyberattacks hit news outlets, opposition, and rights defenders

A wave of extraordinary cyberattacks caused significant disruptions and data breaches over the past year. Millions of unsecured “internet of things” devices like online baby monitors and coffee machines were hijacked and used to strike the Domain Name System provider Dyn with a DDoS attack, resulting in outages at some of the web’s most popular platforms. Showcasing increasingly bold political motivations, hackers also infiltrated the servers of the U.S. Democratic National Committee in 2016 and the campaign of French presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron in 2017.

While these intrusions made headlines, similar attacks have hit human rights defenders, opposition members, and media outlets around the world at a higher rate than ever before, often with the complicity of their own governments. Technical attacks against government critics were documented in 34 of the 65 countries assessed, up from 25 in the 2016 edition. Rather than protecting vulnerable users, numerous governments took additional steps to restrict encryption, which further exposed their citizens to cyberattacks.

Security vulnerabilities present government-affiliated entities with an opportunity to intimidate critics and censor dissent online while avoiding responsibility for their actions. It is often difficult to identify with certainty those responsible for anonymous cyberattacks, including when suspicions of government involvement are high. The likes of China, Ethiopia, Iran, and Syria consistently produce the most pervasive attacks by state-affiliated actors, but the dynamic and weakly regulated market for military-grade cyber tools has lowered the financial bar for engaging in such activity. Even local law enforcement agencies can now persecute their perceived foes with limited oversight. In fact, technical attacks currently represent the second most common form of internet control assessed by Freedom House, behind arrests of users for political or social content.

Activists and media outlets often have only minimal defenses against technical attacks, which can result in censorship, surveillance, content manipulation, and intimidation. Many attacks still go unreported, especially when there are no clear channels to document such incidents, or when the victims fear reprisals for speaking out.

Independent websites are temporarily disabled

Activists and media outlets in at least 18 countries reported service interruptions caused by cyberattacks—especially DDoS attacks, in which simultaneous requests from many computers overwhelm and disable a website or system. These types of attacks have become an easy and relatively inexpensive way to retaliate against those who report on sensitive topics.

Eurasia and Latin America were the regions that featured the most successful attacks. In Azerbaijan, the independent online news platform Abzas reported receiving a series of DDoS attacks that lasted for several days in January 2017. The website was inaccessible until it migrated to a more secure host. A forensic investigation tracked the IP addresses that launched the attack to several Azerbaijani government institutions. Venezuelan news and civil society organizations noted a surge in the number of reported attacks in early 2017. These included an attack against Acción Solidaria, an organization that supports people living with HIV/AIDS in the country. The disruption temporarily prevented the group from informing users about the distribution of medicines.

Hacking enables surveillance of reporters and dissidents

Victims reportedly had their devices or accounts hacked, with suspected political motives, in at least 17 countries. The threat of surveillance can have a chilling effect on the work of journalists, human rights defenders, and opposition political activists, who were specifically targeted in a number of cases during the past year.

Large-scale phishing campaigns such as “Nile Phish” in Egypt attempted to obtain sensitive information from human rights organizations through deceitful emails. In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), spyware developed by the Israeli firm NSO—which says it only markets the technology to law enforcement and intelligence agencies—was employed against human rights defender Ahmed Mansoor, echoing previous reports on government contracts with the Italian company Hacking Team to monitor rights activists.

NSO spyware was also used against prominent Mexican journalists, human rights lawyers, and activists, who received highly personalized and often intimidating messages. One of the many targets was a lawyer representing parents of 43 student protesters who disappeared in 2014. Days after he clicked on a link in a text message purportedly seeking his help, a recording of a call between him and one of the parents appeared online.

Encryption legislation opens a back door to abuse

Rather than taking measures to protect businesses, citizens, and vulnerable groups from these cybersecurity threats, many governments are moving in the opposite direction.

Restrictions on encryption continued to expand, perpetuating a trend that Freedom on the Net has tracked for a number of years. At least six countries—China, Hungary, Russia, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and Vietnam—recently passed or implemented laws that may require companies or individuals to break encryption, offering officials so-called backdoor access to confidential communications.

Encryption scrambles data so that it can only be read by the intended recipient, offering an essential layer of protection for activists and journalists who need to communicate securely. But even democratic governments often perceive it merely as a tool to shield terrorist and other criminal activity from law enforcement agencies.

European countries have been quick to legislate in the wake of terrorist attacks, introducing measures that could compromise security for everyone. Antiterrorism legislation passed in Hungary in July 2016 requires providers of encrypted services to grant authorities access to client communications. The United Kingdom’s Investigatory Powers Act, passed in November 2016, could be used to require companies to “remove electronic protection” from communications or data where technically feasible. “Real people often prefer ease of use … to perfect, unbreakable security,” Home Secretary Amber Rudd said in July 2017. But UN special rapporteur David Kaye has found that encryption and anonymity are essential for upholding free expression and the right to privacy.

Other governments have cited cybersecurity and counterterrorism priorities to justify measures that clearly grant state agencies the power to surveil activists and journalists in the context of harsh crackdowns on dissent. Recent amendments to Thailand’s computer crimes law that could compel service providers to “decode” computer data are particularly concerning. Privacy International has challenged Microsoft for trusting the country’s national root certificates by default, potentially enabling the military government to falsify website credentials, capture users’ log-in details, and downgrade encrypted connections. Similar concerns had been raised in the past over Chinese-issued root certificates and the potential for abuse. In repressive countries like these, private messages are often used to prosecute government critics. A Thai military court sentenced a political activist to more than 11 years in prison in January 2017 based partly on transcripts that supposedly documented a private Facebook Messenger exchange.

How requirements for intermediaries to decrypt all communications will work in practice remains unclear, especially in cases of end-to-end encryption, in which decryption keys are held on the users’ devices rather than on a company’s servers. A low level of technical literacy among policymakers has often translated into legislation that is problematic in terms of both human rights and implementation. In Kazakhstan, for example, moves to facilitate government monitoring of encrypted traffic through a “National Security Certificate” were shelved after authorities realized the law’s impracticalities.

New cybersecurity tools offer some hope for mitigation

Despite these often problematic regulations from governments, private companies are attempting to provide customers with improved security measures. Google has signaled its intention to roll out further protections against “man-in-the-middle” attacks on its Chrome web browser. Like Facebook, Microsoft, Twitter, and others, the company also alerts users who it suspects are victims of an attack by state-sponsored hackers.

While commercial protection can be expensive, some private initiatives have offered free protection for news outlets and human rights sites that cannot afford commercial fees. Examples include Project Shield (Google), Project Galileo (Cloudflare), and Deflect. In one case, Project Shield helped the Angolan independent news site Maka Angola to successfully fend off recurring DDoS attacks.

Such services can assist in combating some of the most pervasive attacks, but civil society organizations and independent media outlets still struggle to keep up with the overwhelming array of tactics used by their opponents in cyberspace, let alone build up the necessary awareness and capacity to proactively prevent and mitigate these threats.

VPNs face rise in both usage and restrictions

VPNs channel an internet user’s entire connection through a remote server, often in a different country, enabling access to content that is blocked domestically; some also encrypt or hide users’ activity from hackers or internet service providers (ISPs). Six countries—Belarus, China, Egypt,Russia, Turkey, and the UAE—stepped up efforts to control these tools in the past year, by either passing legislation that bans censorship circumvention or blocking websites or network traffic associated with VPNs. Such crackdowns often follow periods of aggressive censorship that prompt users to seek out ways to bypass the new information restrictions. The government in Egypt, which began blocking independent news websites for the first time in December 2015, censored at least five websites offering VPNs in 2017.

Campaigns against VPNs are unpopular and difficult to enforce. Many people depend on VPNs for different functions, including corporate employees accessing remote file servers and security-conscious internet users logging onto open Wi-Fi networks in public. In countries that block international news and information, local scientists, economists, and even government officials rely on VPNs to stay informed.

For this reason, no country has sought to ban VPNs completely. Instead, the most repressive states are moving toward a two-tier system that would authorize certain VPNs for approved uses and ban the rest. Even if VPN traffic proves impossible to regulate comprehensively, states can steer users toward domestic providers that are more likely to cooperate with local law enforcement and security agencies, and create laws to penalize anyone caught using a secure connection for the wrong reason.

Chinese authorities passed a series of regulations in the past year, first to license VPN providers, then requiring ISPs to block those that are unlicensed; in July 2017, Apple informed several VPN operators that their apps were no longer accessible through the company’s Chinese app store because they were not in compliance. In the UAE, internet users and businesses scrambled to understand the implications of new amendments to the cybercrime law, which prescribed heavy fines and possible prison terms for the misuse of VPNs to commit fraud or crime. Separately, Russia passed a law obliging ISPs to block websites offering VPNs that can be used to access banned content; Russian authorities raided the local offices and seized servers belonging to one foreign VPN provider, Private Internet Access, in 2016. VPNs have been periodically restricted in at least nine other countries, including Iran, where government authorities reportedly created their own VPN tools that allowed users to access banned content but subjected all of their activities to state monitoring.

Some VPNs are harder to monitor and block, offering stronger security protocols and strict policies against exposing user data. But repressive governments specifically target the more secure tools. Tor, a project that encrypts and anonymizes web traffic by routing it through a complex network of volunteer computers, was subject to new blocking orders amid tightening censorship in Belarus, Turkey, and Egypt. Blocking orders may pertain to the website where users download dedicated software required to access the Tor network, or to traffic from the computers that make up the network itself. Such measures may not eradicate Tor from any one country, but they do make it harder for the general population to access. Users who could not reach the website in the past year continued to share options for downloading the software by email—but those seeking access have to know whom to ask.

Physical attacks on netizens and online journalists spread globally

Physical attacks in reprisal for online activities were reported in 30 countries, up from 20 in the 2016 edition of Freedom on the Net. In eight countries, people were murdered for writing about sensitive subjects online. And in four of those countries—Brazil, Mexico, Pakistan, and Syria—such murders have occurred in each of the last three years. The most frequent targets seem to be online journalists and bloggers covering politics, corruption, and crime, as well as people who express religious views that may contrast with or challenge the views of the majority. Perpetrators in most cases remained unknown, but their actions often aligned with the interests of politically powerful individuals or entities.

Physical violence is a crude but effective censorship tactic, especially in countries where prominent websites provide a key outlet for independent investigative reporting, and where the traditional media are often affiliated with the government. Pavel Sheremet, an investigative journalist with the Ukrayinska Pravda website in Ukraine, was killed by a bomb planted in his vehicle in Kyiv in July 2016. A year later, the murder remained unsolved, and local journalists have exposed serious flaws in the investigation carried out by the Ukrainian authorities.

Journalists in some countries use informal social media channels to supplement or amplify their more formally published work, attracting reprisals. Soe Moe Tun, a print journalist with the Daily Eleven newspaper in Myanmar, was beaten to death less than a week after he republished digital images of his reporting notebooks on Facebook. The notes named individuals who allegedly colluded in illegal logging in the northwestern Sagaing region.

Assailants in several reported cases sought to remove online content. Gertrude Uwitware, a broadcast journalist in Uganda, was abducted for eight hours in April 2017 by unknown perpetrators. They ordered her to delete social media posts in which she had expressed support for an academic who was jailed the same month for calling authoritarian president Yoweri Museveni “a pair of buttocks” online.

Religious groups are also adapting to the internet, and opinions once shared within a restricted circle of acquaintances are more likely to attract the attention of extremists who monitor social media for opportunities to punish perceived insults or apostasy. In Pakistan, where a court recently sentenced an internet user to death for committing blasphemy on Facebook, a student in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province was killed on campus by a mob that accused him of posting blasphemous content online. In September 2016, Christian writer Nahed Hattar was shot dead outside a courthouse in Jordan, where he was on trial for insulting Islam on Facebook with a cartoon satirizing terrorists’ vision of heaven. Such attacks often succeed in silencing more than just the victim, encouraging wider self-censorship on sensitive issues like religion.

The state’s failure to punish perpetrators of reprisal attacks for online speech perpetuates a cycle of impunity. But the government’s harmful role was even more direct in seven countries where individuals detained as a result of their online activities reported that they were subjected to torture. They included Bahrain, where human rights activist Ebtisam al-Saegh said she was sexually assaulted by security agents after her May 2017 arrest for criticizing the state on Twitter.

Censored Topics by Country

Censorship was reflected if state authorities blocked or ordered the removal of content, or detained or fined users for posting content on the topics considered. The chart does not consider extralegal pressures such as violence, self-censorship, or cyber attacks, even where the state is believed to be responsible.

Related posts:

More African governments are trying to control what’s being said on social media and blogs

More African governments are trying to control what’s being said on social media and blogs

Uganda ‘feels’ Tanzania’s tightening grip on social media

Uganda ‘feels’ Tanzania’s tightening grip on social media

Ruling party leaders want social media platforms indefinitely closed.

Ruling party leaders want social media platforms indefinitely closed.

Court sets hearing date for social media shutdown lawsuit

Court sets hearing date for social media shutdown lawsuit

You may like

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

‘Food and fossil fuel production causing $5bn of environmental damage an hour’

Published

2 weeks agoon

December 22, 2025

UN GEO report says ending this harm key to global transformation required ‘before collapse becomes inevitable’.

Related posts:

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

New billion-dollar loans to fossil fuel companies from SEB, Nordea and Danske Bank.

New billion-dollar loans to fossil fuel companies from SEB, Nordea and Danske Bank.

Fossil fuel opponents lobby Africans for support

Fossil fuel opponents lobby Africans for support

Ecological land grab: food vs fuel vs forests

Ecological land grab: food vs fuel vs forests

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Britain, Netherlands withdraw $2.2 billion backing for Total-led Mozambique LNG

Published

3 weeks agoon

December 17, 2025

CONSTRUCTION HALTED IN 2021, BUT DUE TO RESTART

PROJECT CAN PROCEED WITHOUT UK, DUTCH FINANCING, TOTAL HAS SAID

CRITICISM FROM ENVIRONMENTAL, HUMAN RIGHTS GROUPS

Related posts:

Uganda, Total sign crude oil pipeline deal

Uganda, Total sign crude oil pipeline deal

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

NGOs file suit against Total over Uganda oil project

NGOs file suit against Total over Uganda oil project

Agribusiness Company with financial support from UK, US and Netherlands is dispossessing thousands.

Agribusiness Company with financial support from UK, US and Netherlands is dispossessing thousands.

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

The secretive cabal of US polluters that is rewriting the EU’s human rights and climate law

Published

1 month agoon

December 5, 2025

Leaked documents reveal how a secretive alliance of eleven large multinational enterprises has worked to tear down the EU’s flagship human rights and climate law, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). The mostly US-based coalition, which calls itself the Competitiveness Roundtable, has targeted all EU institutions, governments in Europe’s capitals, as well as the Trump administration and other non-EU governments to serve its own interests. With European lawmakers soon moving ahead to completely dilute the CSDDD at the expense of human rights and the climate, this research exposes the fragility of Europe’s democracy.

Key findings

- Leaked documents reveal how a secretive alliance of eleven companies, including Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Koch, Inc., has worked under the guise of a “Competitiveness Roundtable” to get the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) either scrapped or massively diluted.

- The companies, most of which are headquartered in the US and operate in the fossil fuel sector, aimed to “divide and conquer in the Council”, sideline “stubborn” European Commission departments, and push the European People’s Party (EPP) in the European Parliament “to side with the right-wing parties as much as possible”.

- Chevron and ExxonMobil were in charge of mobilising pressure against the CSDDD from non-EU countries. The Roundtable companies endeavoured to get the CSDDD high on the agenda of the US-EU trade negotiations and also worked on mobilising other countries against the CSDDD, in order to disguise the US influence.

- Roundtable companies paid the TEHA Group – a think tank – to write a research report and organise an event on EU competitiveness, which echoed the Roundtable’s position and cast doubt on the European Commission’s assessment of the economic impact of the CSDDD.

While Europeans were told that their governments were negotiating a landmark law to hold corporations accountable for human rights abuses and climate damage, a secretive alliance of US fossil fuel giants was working behind the scenes to destroy it. Collaborating under the innocent-sounding name ‘Competitiveness Roundtable’, eleven multinational enterprises have worked closely to eviscerate several EU sustainability laws, including the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). This Competitiveness Roundtable may be unknown, but its members are a who’s-who of polluting, mainly US, multinationals, including Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Dow. The group seems to have run rings around all branches of the EU and the Trump administration to get what they want: scrapping, or at least hugely diluting, the CSDDD.

Leaked documents obtained by SOMO reveal how, under the pretext of the now-near-magical concept of ‘competitiveness’, these companies plotted to hijack democratically adopted EU laws and strip them of all meaningful provisions, including those on climate transition plans, civil liability, and the scope of supply chains. EU officials appear not to have known who they were up against. But the documents obtained by SOMO show a high level of organisation and strategising with a clear facilitator: Teneo, a US public relations and consultancy company.

The documents indicate that many of the companies involved wanted to stay hidden from view. After all, if it were widely known that a secretive group of mostly American fossil fuel companies like Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Koch, Inc. was working as a coordinated organisation to dilute an EU climate and human rights law, that might raise questions and serious concern among the public and the policymakers they were targeting. Many of the companies in the Roundtable have never publicly spoken out against the CSDDD.

Big Oil’s ‘Competitiveness Roundtable’

The Competitiveness Roundtable is dominated by fossil fuel companies, including three Big Oil companies (ExxonMobil, Chevron, TotalEnergies) and three other companies with activities in the oil and gas sector (Koch, Inc., Honeywell, and Baker Hughes). Other members are Nyrstar (minerals and metals, a subsidiary of Trafigura Group); Dow, Inc. (chemicals); Enterprise Mobility (car rentals); and JPMorgan Chase (finance).

Teneo, the Roundtable’s coordinator, has a track record(opens in new window) of working with fossil fuel companies, including Chevron, Shell, and Trafigura, and was hired by the government of Azerbaijan to handle public relations(opens in new window) when it hosted the COP29 climate conference.

In February 2025, the European Commission published the Omnibus I proposal(opens in new window), which aims to “simplify” several EU sustainability laws, including the CSDDD. The documents obtained by SOMO reveal that the Roundtable companies, which have been meeting weekly since at least March 2025, worked on deep interventions within each of the three EU institutions to get the Omnibus I package to align exactly with their views. The EU institutions are expected to reach a final agreement on Omnibus I by the end of 2025.

The documents reveal that the Roundtable companies’ activities in the Parliament are far more significant than what is visible in the EU Transparency Register(opens in new window). Eight of the Roundtable’s lobbying meetings during the Strasbourg plenary sessions of May and June 2025, listed in the Transparency Register, show Teneo as the only attendee, thereby failing to disclose the names of other Roundtable companies that participated in these meetings. Another three meetings the Roundtable held were not found in the EU Transparency Register(opens in new window) at all.

“Divide and conquer” the Council

In the European Council, the Roundtable plotted to “divide and conquer” EU governments to get the climate article in the CSDDD deleted. In June 2025, during the final weeks of negotiations in the Council on the Omnibus I proposal, the Roundtable discussed lobbying EU government leaders to “intervene politically” to ensure its priorities were included in the Council’s negotiation mandate. Subsequently, German Chancellor Merz and French President Macron reportedly(opens in new window) personally intervened(opens in new window) in the Council’s political process, leading to a dramatic dilution(opens in new window) of the texts(opens in new window) negotiated in the months before the intervention. Several of the changes made to the texts strongly align with the Roundtable’s demands, including delaying and substantially weakening the climate obligations, scrapping EU civil liability provisions, and limiting the responsibility of companies to take responsibility for their supply chains (the ‘Tier 1’ restriction).

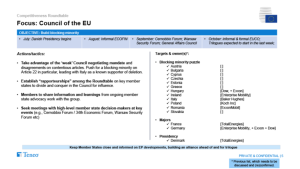

Competitiveness Roundtable meeting document, 11 July 2025.

Additionally, the documents reveal that the Roundtable is still aiming to drum up a “blocking minority” to overturn the Council’s negotiation mandate during the trilogue negotiations, which started in November 2025. By “tak[ing] advantage of the ‘weak’ Council negotiating mandate” and disagreements between EU Member States on “contentious articles”, the Competitiveness Roundtable companies hope to force the Danish Council presidency to give up on including any form of climate obligations in the CSDDD – despite EU Member States’ agreement on this in the June 2025 Council mandate(opens in new window) .

To implement the divide-and-conquer strategy, the Roundtable assigned specific companies to “establish rapporteurships” with different EU governments. TotalEnergies would target the French, Belgian, and Danish governments, and ExxonMobil would target Germany, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Romania.

Circumventing “stubborn” European Commission departments

The Roundtable also discussed working on “circumvent[ing]” two “stubborn” European Commission departments involved in the Omnibus political process, DG JUST and DG FISMA, which, in their view, were “unlikely to be willing to see our side of the story”. According to the documents, DG JUST opposed deleting the climate article and restricting the Directive’s scope to only very large enterprises. The Roundtable aimed to diminish the role of these departments by pressuring President Von der Leyen and Commissioners McGrath (DG JUST) and Albuquerque (DG FISMA) by “organising letters from Irish and German business groups” and using an event held by the European Roundtable for Industry to “target” Von der Leyen and McGrath.

Read full report: Somo.nl

Source: Somo

Related posts:

Victims of human rights violations in Uganda still waiting for redress

Victims of human rights violations in Uganda still waiting for redress

UN Human Rights Chief urges EU leaders to approve key business and human rights legislation

UN Human Rights Chief urges EU leaders to approve key business and human rights legislation

Business, UN, Govt & Civil Society urge EU to protect sustainability due diligence framework

Business, UN, Govt & Civil Society urge EU to protect sustainability due diligence framework

Development financiers fuel human rights abuses – New Report

Development financiers fuel human rights abuses – New Report

COP30 : a further step towards a Just Transition in Africa

‘Food and fossil fuel production causing $5bn of environmental damage an hour’

Four hundred fifty victim families of the Oil Palm project in Buvuma are to receive compensation by this Friday – Witness Radio

Britain, Netherlands withdraw $2.2 billion backing for Total-led Mozambique LNG

Four hundred fifty victim families of the Oil Palm project in Buvuma are to receive compensation by this Friday – Witness Radio

Women’s groups demand equality in land tenure security to boost food production.

Tension as Project-Affected Persons demand to meet Uganda’s President over Oil Palm growing on their grabbed land.

Land commission starts updating govt land countrywide.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center