SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Agribusiness and big finance’s dirty alliance is anything but “green”

Published

4 years agoon

Just prior to Amaggi’s green bond, Brazil’s biggest producer of soybeans, SLC Agrícola, issued its own USD 95 million green bond for what it calls “regenerative agriculture”. SLC’s farms cover 460,000 hectares of land, mainly in the Cerrado,where it has deforested at least 30,000 hectares of native vegetation and where it has been fined several times by Brazil’s federal environmental agency for its activities.4

But the big financial companies want the public to bear the risks for their ventures. Green finance may be promoted by private financial companies but it depends heavily on governments. Only governments can generate demand by implementing laws and policies that force companies to make “green” investments, often in the form of taxes on carbon that are passed on to consumers and that disproportionately penalise the poorest.

One of the fastest growing instruments of green finance, “sustainability-linked” bonds (SLB) and bank loans, takes these weaknesses to an extreme. These bonds and loans are issued without specifying which projects the proceeds are destined for or what the social and environmental benefits will be.

To make this happen, agribusiness companies are working aggressively with corporations from other sectors and corporate-dominated spaces like the Food and Land Use Coalition, the World Economic Forum and The Food Systems Summit to push for so-called “nature-based solutions” with an emphasis on land use and the agricultural sector.27

|

Company

|

Green finance mechanism

|

Notes

|

|

Green bond worth USD 94 million issued in 2020. It was raised in green agribusiness bonds (Agribusiness Receivables Certificates) to be applied in digital and low Carbon Farming Practices, Integrated Systems (Crop-Livestock) in its 460 thousand hectares of soy, maize and cotton monoculture plantations. The green bond was issued through Bradesco bbi, Itaú and Santander banks.

|

The second party opinion (SPO), Resultante, listed in its report several passages linking SLC Agricola with environmental crimes and land grabbing. Although it was approved, the issuance of the green bond was validated with the recommendation of not allocating the funds to those questionable areas.

|

|

|

Sustainability bond worth USD 750 million in 2021 to be applied to its 170 thousand hectares in a mix of environment projects such as renewable energy and land use, as well as in socio-economic activities as job creation. The bond was coordinated by BNP Paribas, Bradesco Securities, Inc., Citigroup Global Markets, Inc., Itaú BBA USA Securities, Inc., JP Morgan Chase & Co., Rabobank and Santander Investment.

|

Amaggi group is the largest exporter of soybean from Brazil and is a major buyer of soybean from known deforesters like SLC Agrícola and BrasilAgro, and has not yet agreedto a 2020 cut-off date for land clearing in the Cerrado region.

|

|

|

Green bond of EUR 75 million (USD 89 million). to be issued in Europe in 2021. Proceeds will be used for various activities including reducing greenhouse gas emissions and expanding its farming operations.

|

AgriNurture Inc. is a company based in the Philippines that received early backing from Cargill’s hedge fund Black River and the Far Eastern Agricultural Investment Company of Saudi Arabia. It has become one of the largest farming companies and agricultural exporters in the country through the development of large-scale farms and plantations, most recently for maize in Mindanao.

|

|

|

Olam has secured three “green” loan facilities since 2018 from different consortiums of banks: a sustainability-linked loan of USD 500 million in 2018, a USD 525 million sustainability-linked revolving credit facility in 2019 and a USD 525 million sustainability loan in 2020– all to be used for general spending but with an interest margin dependent on Olam’s ability to meet various targets. In 2019 it launched the world’s first “digital loan” of USD 350 million.

|

Olam is an Indian non-resident company based in Singapore. It is one of the world’s largest commodity traders and has invested heavily in farming operations and contract farming schemes, particularly in Africa and Latin America. It is part-owned by Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund Temasek and Japan’s Mitsubishi. It claims to have 2.4 million hectares under direct management, including a controversial 144,000 hectare oil palm plantation concession in Gabon.

|

|

|

Sustainability-linked loan with 20 banks, worth USD 2.3 billion in 2019. ING, BBVA and Rabobank acted as sustainability coordinators. ABN AMRO has acted as coordinator and facility agent.

|

It was the largest loan by an agricultural trader. The loan is linked to a general year-on-year improvement target of ESG performance, assessed by SPO Sustainalytics and increasing its traceability of Brazilian agri-commodities. In late 2020, the World Bank’s International Financing Corporation (IFC) began subsidising the traceability of the direct suppliers of soybean in Matopiba, in the Cerrado region (Brazil).

|

|

|

In July 2021, Samunnati issued a USD 4.6 million agricultural green bond via the market platform Symbiotics. The proceeds are to be “fully allocated towards climate smart agriculture.”

|

Samunnati is an Indian micro-credit lender for farmers and agribusiness. Its investors include the US pension fund TIAA and the US government’s International Development Finance Corporation.

|

|

|

A ten-year loan of USD 50 million to soybean suppliers in Cerrado to support a deforestation-free target. This is Santander Bank and The Nature Conservancy (“TNC”) financial mechanism that is not formally considered as green finance, but that links the expansion of soy to a “compliance with environmental law” in Brazil.

|

The Responsible Commodities Facility (RCF) and the Soft Commodities Forum Platform, bring together giant agribusiness traders (ABCD, Cofco, Viterra -ex Glencore Agriculture) to issue new “green” agribusiness debt instruments for the expansion of soybean plantations over pasture areas.

|

|

|

Cargill

|

Land Innovation Fund, created with Cargill’s USD 30 million to support the expansion of soybean over degraded pasture areas in Argentina and Paraguay’s Cerrado and Grand Chaco. The fund is incorporating the suppliers into a traceability chain for measuring soil carbon emissions. The Bank of Cargill is increasing its use of agribusiness bonds to fund soybean suppliers, with a rise of 30% in 2020 in Agribusiness Letters of Credit. The company is part of the Brazilian Initiative

for Green Finance to support the emission of green bonds in agriculture.

|

Cargill is perhaps the soybean trader most linked to deforestation and fires in their supply chain. In 2019, Nestlé stopped sourcing all of its purchases of Brazilian soy from Cargill with the trader not being able to trace soybeans from its suppliers. In 2020, Norwegian Grieg Seafood did not allow any funds from its Green Bond worth USD 103 million to be used to purchase feed supply from Cargill until the company had significantly reduced itsrisk of soybean-related deforestation in Brazil.

|

|

Onesustainable transition bond worth USD 500 million issued in 2019 through BNP Paribas, ING and Santander, to purchase deforestation-free cattle from direct suppliers in Amazonia.

Onesustainability-linked loan worth USD 30 million in 2021 as part of green financing to support Mafrig’s transition to a no-deforestation requirement across its entire chain.

|

The first labelled “transition bond” issued in the world, after the green bonds held by one of the world’s biggest beef producers were refused by investors. The bond was re-labelled to support high-emitting companies that do not fit green bonds requirements to clean up their supply chain. Only two other transition bonds of this kind were issued in 2020 due to the lack of reliability.

|

|

|

Green bond worth USD 5 million issued as a green agribusiness bond (Agribusiness Receivables Certificates) to support the expansion of regenerative and organic agriculture production in its 1200 hectares located in São Paulo, Brazil. It was structured by the financial consultancy Ecoagro.

|

The first certified agriculture green bond issued in the world, according to the new CBI principles for the agriculture sector. According to Rizoma’s founding partner, Pedro Paulo Diniz, regenerative agriculture has the potential to offset “more than 100% of human carbon emissions” and often “has more biodiversity than a native forest”.

|

|

|

Ventisqueros

|

Chilean salmon farmer Ventisqueros announced at the end of 2020 that it had landed a USD 120 million green loan from banks Rabobank and DNB. The proceeds will fund the expansion of production from the current 40,000 metric tonnes to 60,000 metric tonnes.

|

In 2019, there was a massive escape of salmon from one of Ventisqueros’ farms in Chiloé leading to a complaint from the National Fisheries and Aquaculture Service (Sernapesca) before the Superintendency of the Environment and in court. The company has also refused to comply with a sentence issued by the Council for Transparency ordering them to provide Oceana with data on their use of antibiotics in 2015, 2016 and 2017.

|

|

Mowi

|

Mowi completed a USD 165 million green bond in 2020, the first green bond issued by a seafood company. The proceeds will be used for green projects as defined by Mowi’s green bond framework.

|

Norway-based Mowi is the world’s largest aquaculture company and largest salmon producer. It is notorious for the aggressive tactics it deploys against critics and for the damage it has caused to the environment, particularly to wild salmon stocks.

|

|

Long-term loan for the recovery of degraded pasture areas by soybean planting via the Reverte programme, led by Syngenta in partnership with TNC and Itaú bank. Although not formally a “green loan”, the Itaú bank already reserved USD 86 million to “restore” 30 thousands hectares in Cerrado with soybean and other inputs provided by Syngenta.

|

The Reverte programme announced by Syngenta aims to “restore” 1 million hectares by 2025. In addition to using green finance to sell inputs and the obligation to use the traceability system, the Syngenta Group traded the seeds in exchange for the soybean harvest (barter operation) and operated the export of the company’s first cargo ship of soybeans from Brazil to China.

|

|

|

Three Green bonds totalling USD 639 million in 2020 and 2021 coordinated by Morgan Stanley to produce ethanol from maize and produce 100% renewable energy.

One sustainability-linked bond worth USD 26 million with Credit Suisse Bank and one sustainability-linked loan of USD 33 million in 2020 with Santander bank, conditioned to: reducing the carbon footprint; improving the traceability of suppliers, and disclosure and transparency in its annual reports.

|

This was the first green agribusiness bond for the bioenergy sector, called Agribusiness Receivable Certificates (CRA). The company produced 100% of ethanol for maize. The bioenergy sector, along with the forestry sector, is one of the biggest issuers of green and sustainability bonds.

|

|

|

Suzano S.A.

|

Four Green bonds since 2016 totalling USD 1.6 billion for pulp and paper industrial forestry. The offering was coordinated by J.P. Morgan, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, BNP, Crédit Agricole, MUFG, Santander, Rabobank, SMBC Nikko, Scotiabank and Mizuho.

Two sustainability-linked bonds (SLB) totalling USD 1.2 billion in 2020 and another USD1 billion SLB issued in June 2021, through BNP Paribas, BofA, J.P. Morgan, Mizuho, Rabo Securities and Scotiabank.

Onesustainability-linked loan worth USD 1.6 billion in January 2021 operated by BNP Paribas.

Both SL bonds and loans are linked to reducing the company’s direct emissions and water consumption across all its operations and purchases (scopes 1 and 2) and also have an “inclusion” target to have woman in leadership positions.

|

Suzano was the first issuer of green bonds and sustainability-linked bonds in Brazil and has 37% of its debts tied to green finance. Suzano S.A has more than 1 million hectares of industrial pine and eucalyptus monoculture plantations in Brazil and is historically linked to a series of human rights violations against local communities and the labour rights of its workers.

|

|

Sustainability bond worth USD 95 million issued in 2018 by the USAID initiative Tropical Landscapes Financing Facility (TLFF) through BNP Paribas in partnership with WWF. The bond was issued to fund 88 thousand hectares of rubber plantation for PT Royal Lestari Utama (RLU), an Indonesian joint venture between France’s Michelin and Indonesia’s Barito Pacific Group.

|

Asia’s first sustainability debt instrumentand part of the Memorandum of Understanding between UN Environment and BNP Paribas that was signed at the One Planet Summit in Paris in December 2017. The target is to reach USD 10 billion of innovative sustainable finance by 2025 for projects that support sustainable agriculture and forestry in ways that help solve the climate crisis.

|

Related posts:

The global farmland grab goes green

The global farmland grab goes green

World Bank branch indirectly backs coal megaproject despite green pledge

World Bank branch indirectly backs coal megaproject despite green pledge

International Finance Corporation Should Stop Bankrolling Destructive Agribusiness

International Finance Corporation Should Stop Bankrolling Destructive Agribusiness

EBRD launches new agribusiness strategy

EBRD launches new agribusiness strategy

You may like

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Global use of coal hit record high in 2024

Published

4 weeks agoon

November 3, 2025

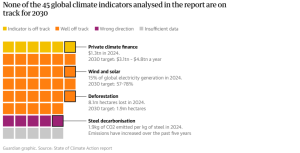

Bleak report finds greenhouse gas emissions are still rising despite ‘exponential’ growth of renewables.

Coal use hit a record high around the world last year despite efforts to switch to clean energy, imperilling the world’s attempts to rein in global heating.

The share of coal in electricity generation dropped as renewable energy surged ahead. But the general increase in power demand meant that more coal was used overall, according to the annual State of Climate Action report, published on Wednesday.

The report painted a grim picture of the world’s chances of avoiding increasingly severe impacts from the climate crisis. Countries are falling behind the targets they have set for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, which have continued to rise, albeit at a lower rate than before.

Clea Schumer, a research associate at the World Resources Institute thinktank, which led the report, said: “There’s no doubt that we are largely doing the right things. We are just not moving fast enough. One of the most concerning findings from our assessment is that for the fifth report in our series in a row, efforts to phase out coal are well off track.”

If the world is to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050, in order to limit global heating to 1.5C above preindustrial levels, as set out in the Paris climate agreement, then more sectors must use electricity instead of oil, gas or other fossil fuels.

But this will work only if the global electricity supply is shifted to a low-carbon footing. “The trouble is that a power system that relies on fossil fuels has huge cascading and knock-on effects,” said Schumer. “The message on this is crystal clear. We simply will not limit warming to 1.5C if coal use keeps breaking records.”

Though most governments are supposed to be aiming to “phase down” coal use after a commitment made in 2021, some are pushing ahead with the most polluting fuel. India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, celebrated surpassing 1bn tonnes of coal production this year, and in the US Donald Trump has declared his support for coal and other fossil fuels.

Trump’s efforts to halt renewable energy projects, and remove funding and incentives for switching to low-carbon power sources, have largely not made themselves felt yet in the form of higher greenhouse gas emissions. But the report suggested these efforts would have an effect in future, though others, including China and the EU, could blunt the impact by continuing to favour renewables.

The good news is that renewable energy generation has grown “exponentially”, according to the report, which found solar to be “the fastest-growing power source in history”. This is still not enough, however: the annual growth rates of solar and wind power need to double for the world to make the emissions cuts needed by the end of this decade.

Sophie Boehm, a senior research associate at the WRI’s systems change lab and a lead author of the report, said: “There’s no question that the United States’ recent attacks on clean energy make it more challenging for the world to keep the Paris agreement goal within reach. But the broader transition is much bigger than any one country, and momentum is building across markets and emerging economies, where clean energy has become the cheapest, most reliable path to economic growth and energy security.”

The world is moving too slowly on improving energy efficiency, in particular cutting the carbon generated by heating buildings. Industrial emissions are also a concern: the steel sector has been increasing its “carbon intensity” – the carbon produced with each unit of steel manufactured – despite efforts in some countries to move to low-carbon methods.

Electrifying road transport is moving faster – more than one in five new vehicles sold last year was electric. In China, the share was closer to half.

The report also sounded a warning on the state of the world’s “carbon sinks” – forests, peatlands, wetlands, oceans and other natural features that store carbon. While nations have repeatedly pledged to protect their forests, they continue to be cut down, albeit at a slower rate in some areas. In 2024, more than 8m hectares (20m acres) of forest were permanently lost. That is lower than the high of nearly 11m hectares reached in 2017, but worse than the 7.8m hectares lost in 2021. The world needs to move nine times faster to halt deforestation than governments are managing, the report found.

World leaders and high-ranking officials will meet in Brazil next month for the Cop30 UN climate summit, to discuss how to put the world on track to stay within 1.5C of global heating in line with the 2015 Paris climate agreement. Each government is supposed to submit a detailed national plan on emissions cuts, called a “nationally determined contribution”. But it is already clear that those plans will be inadequate, so the key question will be how countries respond.

Source: theguardian.com

Related posts:

African Development Bank decides not to fund Kenya coal project

African Development Bank decides not to fund Kenya coal project

World Bank branch indirectly backs coal megaproject despite green pledge

World Bank branch indirectly backs coal megaproject despite green pledge

Banks have given almost $7tn to fossil fuel firms since Paris deal, report reveals

Banks have given almost $7tn to fossil fuel firms since Paris deal, report reveals

30 civil society organizations have written to the World Bank Group demanding to publicly disclose the Africa Energy Approach paper.

30 civil society organizations have written to the World Bank Group demanding to publicly disclose the Africa Energy Approach paper.

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

The Environmental Crisis Is a Capitalist Crisis

Published

4 weeks agoon

November 3, 2025

One of humanity’s greatest challenges today is the environmental crisis, which threatens our very existence. Our latest dossier explores its class character, showing that the climate catastrophe is a product of capitalism’s relentless drive for accumulation.

The photographs in this dossier were taken by Sebastião Salgado, one of Brazil’s – and the world’s – greatest photographers. He passed away in May 2025, leaving behind an artistic legacy inseparable from his commitment to humanity and the preservation of the environment. Salgado travelled the globe portraying peoples, territories, and workers with dignity, capturing life’s beauty while bearing witness to an era marked by capitalism’s brutality against humanity and nature. His photographs, like this dossier, remind us that we cannot remain mere spectators of destruction: we must be agents of change.

We are grateful to the team that safeguards his legacy and, in a spirit of solidarity, authorised the use of his images to enrich and strengthen this dossier.

Capitalism Will Not Solve the Environmental Crisis

The environmental crisis is one of the greatest challenges we face today. At its root lie the capitalist mode of production and the logic of capital accumulation pursued by the ruling classes of the Global North and South. The devastation wrought by capitalism is plain for all to see, as climate change intensifies and accelerates year after year, threatening the very existence of humanity. As Fidel Castro warned in his speech at the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro, ‘An important biological species is in danger of disappearing due to the rapid and progressive liquidation of its natural living conditions: humanity’.1

Many international organisations and bodies have sought solutions to the environmental crisis, but always within the framework of capitalism. In November 2025, the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) will be held in Belém, Pará, in the Amazon region of Brazil. The Amazon is home to countless generations of Indigenous peoples who, through their interaction with nature, have allowed the planet’s most biodiverse ecosystem to flourish.

Today, the Amazon is the site of one of capitalism’s central contradictions: agribusiness destroys it by burning and clearing land to expand the agricultural frontier while the very same land is financialised by transnational corporations trading its territories as carbon reserves on stock exchanges. While the ruling classes insist on presenting the environmental crisis as a problem for all of humanity – without any class distinctions – we must not forget that the class contradictions inherent to capitalism are also reflected in the environmental question. In fact, those most affected by climate disasters are the urban and rural poor, who live under precarious conditions in hazard-prone areas.

One of the main tasks in the battle of ideas is therefore to politicise the debate around the environmental crisis by showing its class character – something that is urgently needed, as reflected by a recent survey that found that more than 30% of Brazil’s population is unaware of climate change, with this figure rising to over 50% among the lowest income groups.2

In light of this reality, this dossier seeks to popularise the debate on the environmental crisis from a Brazilian and Global South perspective in dialogue with working-class organisations. In this dossier, we analyse the causes of the environmental crisis and examine, and critique, proposals for a transition to a low-carbon economy. By seeking alternatives within capitalism, such proposals create new forms of accumulation without resolving the root problem. Finally, we present popular solutions to the crisis along with a set of demands that have emerged from the accumulated experience of Brazil’s popular movements.

Serra Pelada Goldmine, Pará, Brazil, 1986. © Sebastião Salgado

The Destruction of Life and the Logic of Capital

Climate change is the most visible and urgent aspect of the environmental crisis. Chemical pollution, loss of soil cover, ocean acidification, biome destruction, and the loss of biodiversity are also fundamental dimensions of the crisis. As Vijay Prashad rightly pointed out:

One million of the estimated eight million species of plants and animals on the planet are threatened with extinction. The main threat to the majority of species at risk of extinction is biodiversity loss caused by the capitalist agribusiness system of food production. Agricultural production – currently accounting for more than 30% of the world’s habitable land surface – is responsible for 86% of projected losses in terrestrial biodiversity because of land conversion, pollution, and soil degradation.3

The environmental crisis manifests in ways that underscore its inseparability from the class struggle. We see this in the floods that devastated southern Brazil in 2024; the heatwave and then floods that hit Pakistan in 2022, leaving millions homeless while elites remained protected; the 2018 floods in Kerala, India; the 2022 flooding and blackouts in Cuba caused by Hurricane Ian – a phenomenon intensified by rising ocean temperatures; and the increasingly extreme cycles of floods and droughts in the Horn of Africa. From 2019 to 2020, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia faced heavy rains followed by devastating floods. From 2020 to 2023, these countries faced one of the longest droughts in the past seventy years, only to be hit by new floods in 2023–2024. These instances show that the environmental crisis is deepening.4

The main factor driving climate change is the high level of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from fossil fuels as energy consumption from these fuels continues to rise year after year. If we take a closer look at global emission levels, the data once again speaks volumes: the richest 10% are responsible for nearly twenty times more emissions than the poorest 50%.5

Moreover, both historic and current GHG emissions are directly linked to inequality – not only between the Global North and South but also between the richest and poorest segments of the global population. According to the Global Carbon Project, the twenty-three most developed countries account for half of all CO2 emissions since 1850. The United States alone has emitted 24.6% of all carbon released into the atmosphere, followed by Germany (5.5%), the United Kingdom (4.4%), and Japan (3.9%). The other half of emissions is spread across more than 150 countries.6

Recent data shows that this reality has not changed: according to a 2022 study by Climate Watch, the World Resources Institute’s data platform, the ten largest emitters are still responsible for 76% of global CO2 emissions. In 2022 China was the largest emitter of CO2, followed by the United States, India, Russia, and Japan, which would make Asia the planet’s biggest emitter today.7

However, because the populations of countries such as China and India are much larger than those of the United States, European countries, Japan, or Australia, measured in per capita emissions the United States is by far the world’s largest CO2 emitter, with a per capita rate twice that of China and eight times higher than India’s.8

Globally, the fossil fuel industry is the largest emitter of CO2, with roughly one hundred companies responsible for 71% of global historical CO2 emissions, according to a Carbon Majors report published in 2017.9

Among them are giants such as ExxonMobil, Shell, BHP Billiton, and Gazprom. Another 2019 study by the Climate Accountability Institute found that just twenty companies have been responsible for one-third of all global CO2 emissions since 1965.10

Agribusiness is another structural driver of GHG emissions. In 2023 alone, 3.7 million hectares of forest were cleared worldwide, largely for cattle ranching and industrial crops. Over the past twenty years, the sector’s production chain – from fertilisers to processing and transport – has increased its emissions by 130%.11

Though the energy sector accounts for approximately three-quarters of GHG emissions on a global scale, it is worth taking a closer look at countries where raw materials dominate exports. Brazil is a striking example of this: according to the Plan for Ecological Transformation published by the Ministry of Finance, agribusiness is the country’s largest source of GHG emissions, directly accounting for 29% of the total. Deforestation-related emissions add another 38%, with livestock and agriculture responsible for about 96% of deforested land, according to the 2022 Annual Deforestation Report. Taken together, agribusiness is responsible for roughly 67% of Brazil’s total GHG emissions, compared to just 23% from energy generation.12

Predatory extractive practices also play a major role, especially in Global South countries, from mining to the purchase of natural and Indigenous reserve lands by foreign interests as carbon market assets.

Despite regional and national differences, what is clear is that climate change and the destruction of nature are direct consequences of the logic of capital accumulation advanced by the ruling classes.

Kuningan District, Jakarta, Indonesia, 1996. © Sebastião Salgado

Green Capitalism: Supposed Alternatives to the Environmental Crisis

Various socialist currents have raised ecological concerns since the early days of capitalism, from the nineteenth-century socialist and artist William Morris to the environmental and countercultural movements of the mid-twentieth century. Yet it was only in the 1970s, more than a century after the first industries appeared, that the environment became a matter of concern for nation-states and began to gain prominence on the international political agenda. The 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, held in Stockholm, Sweden, was a milestone in advancing the environmental question. As Andrei Cornetta notes:

In addition to population growth in a context of resource scarcity, [the conference] also discussed how to bring various forms of [water, air, and soil] pollution under control at a time when the global energy crisis was on the agenda, especially after the impact of the oil shock of 1973.13

Despite the urgency of the environmental question, no new forms of organising production or relating to nature were proposed at the conference: rather, all alternatives fit within the capitalist mode of production. Meanwhile, growing social and economic inequality between the imperialist core and the dependent periphery sharpened the debate, especially regarding whether to continue developing or to restructure the industrial model along ‘zero growth’ lines.14

In 1979, the First World Climate Conference in Geneva acknowledged the seriousness of ongoing climate change. It was not until 1992 that the Second United Nations Conference on Environment and Development took place in Rio de Janeiro, where a multilateral agenda to address the climate question was proposed. This agenda entered into force in 1994 and served as the precursor to the Conference of the Parties (COP), the decision-making body for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change which meets biennially to review and advance the convention.

Among the many outcomes of the COP process, two stand out. First, the Kyoto Protocol, adopted after COP 3 in 1997, which set binding quantitative targets for reducing GHG emissions for Annex I countries (those that had been industrialised the longest). Second, the Paris Agreement, adopted after COP 21 in 2015, which required signatory countries to set their own emission reduction targets, known as Intended Nationally Determined Contributions.15

However, the targets were never met and both the Kyoto and Paris agreements ended up as failures.

In response to the urgency of climate change, some states have promoted a transition to a low-carbon economy aimed at reducing the amount of harmful GHG emissions – without, of course, touching the profits of major corporations and the capitalist core. From this approach emerged so-called ‘green capitalism’ alternatives, including carbon markets, offset schemes, and energy transition policies.

The Kyoto Protocol emission targets, initially intended to curb air pollution, soon became the basis for a new form of capital accumulation via so-called carbon credits16

that are traded on stock exchanges and function as a kind of ‘license to pollute’.17

This system involves not only financial capital but also significant technological and scientific developments that measure and calculate carbon emissions. They also project potential reductions by modelling what emissions would have been in the absence of offset activities. These offset schemes include reducing emissions caused by deforestation and forest degradation as well as promoting forest conservation, sustainable management, and an increase in forest carbon stocks. However, in practice, once companies exceed their GHG emission limits, they can buy carbon credits on the stock exchange to offset their emissions. Thus, the biophysical process by which plants absorb carbon from the air and convert it to oxygen through photosynthesis – a natural function of plant life and part of the commons – is turned into a commodity.

The main contradiction of green capitalism is that the same agribusiness, oil, and mining transnational corporations that shape the environmental agenda in international bodies and national governments are also those that most aggressively exploit the commons. The agribusiness sector, which drives deforestation and burning in the Cerrado and Amazon biomes18

in order to expand the agricultural frontier, also touts the digitalisation of its production chains, which certify that its products are deforestation-free and decarbonised. Similarly, oil corporations are involved in energy transition policies, and mining companies promote carbon market schemes.

In Brazil, agribusiness – the main source of the country’s GHG emissions – has made sustainability a central theme of its ideological campaign. Far from a genuine commitment to sustainability, this serves as a way to expand into other sectors, increase political influence, and boost profits.19

The agribusiness model – based on large-scale monocultures and the extensive use of pesticides – is among the most damaging to the environment. Yet while companies pursue new avenues of profit through the financialisation of nature and a discourse of sustainability, their production model has not changed; on the contrary, it continues to drive deforestation, burning, and the poisoning of soil, water, and air.

By playing an active role in advancing false solutions to the environmental crisis, the very sectors that most damage the environment have found new ways to profit from the financialisation of nature. These sectors are present not only in government ministries across many countries, but also in international climate bodies and conferences such as the COP. The environmental agenda has long been captured by transnational corporations, and the alternatives they propose never challenge the profit rates of big capital. Brazilian agribusiness, with its rhetoric of sustainability, is among the key players in these international bodies. Brazilian companies such as Suzano Papel e Celulose,20

the food multinational JBS, and the mining corporation Vale all play a major role in ‘sustainability’ projects and the carbon market. For them, offset schemes have become a lucrative form of capital accumulation.

Take, for example, the Maísa project in the Brazilian state of Pará, run by the leading carbon market certifier Verra. The project was meant to preserve a 26,000-hectare stretch of the Amazon rainforest that included the Sipasa Farm, yet the designated protection area later became a mining site, and in early 2024 sixteen farm workers were rescued from conditions comparable to slavery. The fallacy – and failure – of such projects is clear: they serve transnational giants like iFood, Uber, Spotify, Audi, and Google, which pour millions of dollars into offset schemes to cover the emissions generated by their own activities.21

In addition to commodifying one of nature’s commons, projects like Maísa harm biodiversity and undermine the way of life of Indigenous communities who, through the labour of countless generations, have helped shape these forests and their biodiversity. By promoting solutions that fail to confront the destructive logic of capitalist accumulation, such schemes destroy ways of life that have coexisted in harmony with nature for millennia.

The 2019 report by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services paints an alarming picture of ecological collapse brought on by such projects:

One million of the roughly eight million plants and animal species are threatened with extinction; human activity has driven at least 680 vertebrate species to extinction since 1500, while global populations of vertebrate species have fallen by 68% over the last fifty years; the abundance of wild insects has fallen by 50%; and by 2016, more than 9% of all domesticated mammal breeds used in food and agriculture had gone extinct, with another thousand breeds now facing extinction.22

One thing is clear: there are no capitalist solutions to a crisis created by capitalism. If we are to save the Earth and humanity, the answers must come from beyond capitalism.

Cuiabá Farm, Xingó Backlands, Sergipe, Brazil, 1996. © Sebastião Salgado

Popular Perspectives on the Environmental Question

At the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro, Fidel Castro underscored the urgency of the environmental crisis from an emancipatory perspective and condemned the unjust economic and social order between dependent countries in the periphery and those at the capitalist core:

It must be said that consumer societies are primarily responsible for the atrocious destruction of the environment… With only 20% of the world’s population, they consume two-thirds of the metals and three-quarters of the energy produced worldwide. They have poisoned the seas and rivers, polluted the air, weakened and perforated the ozone layer, and saturated the atmosphere with gases that alter the climate with catastrophic effects from which we are already beginning to suffer… It is impossible to blame this on the countries of the Third World – yesterday’s colonies, today’s exploited and plundered nations by an unjust world economic order… If we are to save humanity from this self-destruction, we must achieve a fairer distribution of the wealth and technology available on the planet – less luxury and less waste in a few countries so that there may be less poverty and less hunger across much of the Earth.23

What is at stake is nothing less than the survival of human life on Earth. The environmental crisis is a product of the crisis of capital, which not only fails to resolve problems such as hunger and inequality but deepens them while relentlessly seeking new ways to generate profit for the ruling classes. The environmental struggle must therefore be waged as a direct confrontation with, and ultimate overcoming of, the capitalist mode of production. Unless we challenge the logic of capital – based on the exploitation of working-class labour and the plunder of the Global South – we will not be able to confront the environmental crisis.

The struggle for climate justice must combat not only inequality between the Global North and South but also environmental racism, as it is the poorest, and disproportionately Black and Brown, populations in the Global South that are the most exposed to the effects of the environmental crisis. In Brazil, for example, a study found traces of glyphosate – one of the most widely used pesticides in agribusiness – in breast milk across several regions. Meanwhile, the environmental crimes committed by the mining transnationals Samarco, Vale, and BHP Billiton in the cities of Mariana (2015) and Brumadinho (2019), in Minas Gerais state, not only killed nearly 300 people but also devastated the biodiversity of the Doce River, which runs through Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo, disrupting the way of life of numerous comunidades ribeirinhas<24 (river communities).25

Brazil’s Black population, which is concentrated in urban peripheries, is also disproportionately affected by the environmental crisis, such as in the form of frequent floods and landslides. Women, too, are more acutely impacted than the general population; in rural areas, for example, it often falls on them to handle the pesticides that the agribusiness production model imposes on peasant families. Environmental and climate justice movements must therefore build close connections with antiracist and feminist struggles. The environmental crisis cannot be solved without confronting all forms of social inequality, from racism to patriarchy.

Among the many fronts of struggle, peasant movements linked to La Vía Campesina stand out. Their agenda calls for:

- Popular Agrarian Reform and the Defence of Peasant and Indigenous Territories. Popular Agrarian Reform is the struggle to democratise access to land, directly confront latifundios (large, landed estates), and combat the concentration of land in the hands of the few. This demand goes beyond land redistribution: it challenges the agribusiness model that commodifies nature and deepens the environmental crisis. The struggle for land is tied to the protection of Indigenous and quilombola lands, recognising land concentration as a colonial legacy that must be overcome. By defending peasant and Indigenous territories, La Vía Campesina seeks to ensure that land fulfils its social function as a space for life, work, and cultural reproduction rather than being reduced to a financial asset.

- Food Sovereignty. Food sovereignty is the right of peoples to decide what to produce, as well as for whom and how to produce it, and to guarantee access to healthy and culturally appropriate food. It stands in opposition to the logic of agribusiness, which prioritises export commodities over feeding the people. To achieve food sovereignty, it is essential to support regional food cultures, strengthen short supply chains, and prevent food production from being controlled by large corporations. In order to achieve food sovereignty, public policies must be enacted that strengthen peasant agriculture and ensure that food is treated as a right, not a business; such policies include mandating the institutional purchase of agroecological products and support of those markets.

- Agroecology. Agroecology calls for a radical change in the technological model of agriculture, replacing the predatory system of agribusiness with diversified forms of production that are in harmony with nature. This includes the use of bio-inputs, agroforestry, and sustainable soil management, which create biodiverse environments that are resilient to climate change. Beyond its technical dimension, agroecology is a political practice that builds new relationships between human beings and nature based on cooperation, peasant autonomy, and the recovery of traditional knowledge.

- Care for the Commons. Water, minerals, seeds, land, and biodiversity are not mere ‘natural resources’ or ‘raw materials’ to be exploited: they are commons that are essential to life. Protecting the commons is central to building a popular project for the countryside in which nature is not commodified but rather cared for as collective heritage, ensuring their care for current and future generations.

A central component of Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) is to plant trees and produce healthy food. This is an integral part of building popular agrarian reform, since overcoming the environmental crisis will only be possible through a new model of rural production based on agroecology and new social relations that overcome patriarchy, racism, and LGBTphobia while fostering cooperation and solidarity. As MST leader João Pedro Stédile said about the particular challenges that Brazil faces with respect to the environmental crisis (though his words apply to the Global South more broadly):

We need zero deforestation. There is no need to cut down a single tree to meet the people’s needs. We must ban the export of timber and gold and impose strict controls over mining activities and their environmental impacts. The country needs a publicly funded national reforestation plan to recover millions of hectares throughout the territory. To tackle pollution, mitigate rising temperatures, and confront the problem of individual transportation powered by fossil fuels, we must provide a plan for free, high-quality mass public transport, reforest major cities, and expand the use of solar energy in as many productive activities as possible. In the countryside, agrarian reform must advance with a national agroecology programme that produces healthy food free of agrotoxins for all the people.26

Another perspective that has emerged from social struggles in Latin America, especially in Ecuador and Bolivia, is buen vivir (good living), whose principles were incorporated into the new constitutions of both countries under presidents Rafael Correa and Evo Morales, respectively. Drawing on Indigenous traditions, buen vivir challenges capitalist notions of progress and development and is based on five principles: 1) a holistic vision, or Pacha;27

2) embracing multipolarity; 3) the search for balance; 4) the complementarity of diversity; and 5) decolonisation.28

Ecosocialism, for its part, is a political and theoretical current that combines socialism with radical ecology, criticising both capitalism and traditional socialism for ignoring the planet’s ecological limits. It aims to build an egalitarian and sustainable society in which the economy is reorganised to meet human needs without destroying the environment. For Michael Löwy, one of ecosocialism’s leading theorists, the central dilemma facing the working classes in the twenty-first century is the environmental crisis, which must be addressed from a socialist perspective that conceives of a new mode of production attuned to ecological challenges.

The environmental crisis will not be resolved by the ruling classes. This is the task of the rural and urban working classes. We must create another way of producing and reproducing life that is based on healthy relations between human beings and the environment and built through popular organisation. This path forward must expose the true culprits of the crisis and advance proposals that prioritise all forms of life over profit.

Pico da Neblina, Yanomami Indigenous Territory, Amazonas, Brazil, 2014. © Sebastião Salgado

A Minimum Agenda to Confront the Environmental Crisis

Brazil’s popular movements understand the need to wage struggles on multiple fronts. Despite the limits of the COPs and the negotiations held there, popular movements recognise that it is essential to pressure their governments to secure a minimum agenda that holds the social classes and countries most responsible for pollution accountable and combats the climate catastrophe driven by capitalism. In this spirit, working alongside the MST, we created an agenda to confront the environmental crisis:

I. Compliance with and Advancement of International Agreements

- Building on the agreements of the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, which established the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’, compel Global North countries – which bear historical responsibility for the climate crisis – to rapidly cut their carbon emissions and prevent global temperatures from rising above the critical 1.5°C threshold.

- Ensure that Global North countries provide climate compensation to Global South countries for the losses and damages caused by their carbon emissions and provide substantial funding for public infrastructure to replace reliance on carbon-based energy.

- Fulfil the Paris Agreement pledge that Global North countries provide $100 billion annually to meet the needs of Global South countries, particularly for policies that mitigate the real and disastrous impacts of climate change that they are already experiencing (especially low-lying nations and small island states). These resources must come in the form of grants directly transferred to subnational projects for forest protection and restoration. Since loans are not transfers of resources, they should not be considered to fit within the scope of the Paris Agreement, though this has often been the case. These funds should serve as instruments of climate justice, not as pretexts for financial sector profit obtained through private or multilateral development banks.

- Transfer technology and financing to Global South countries to phase out carbon-based energy systems and build alternatives based on sovereign national strategies.

- Hold Global North countries accountable for polluting water, soil, and air with toxic and hazardous waste – including nuclear waste – such as by making them bear the costs of cleanup and by prohibiting technologies and modes of production that generate such waste.

II. A Planned and Just Energy Transition with Social Participation

An energy transition programme is needed to adapt carbon-based energy systems in order to mitigate their environmental impact. It must be carefully planned, carried out with broad social participation, and supported by financing channels for Global South countries that respond to their specific needs. In addition, it must diversify the energy grid, improve energy efficiency, and guarantee the raw material supply needed for any future energy transition. This programme must:

- End direct and indirect government subsidies for the fossil fuel industry.

- Aggressively increase taxes on emissions and polluting products.

- Prohibit the financial sector’s participation in the fossil fuel industry in order to prevent any transition from being driven by financial speculation.

- Receive state investments in order to combat the climate catastrophe, protect and support affected populations, and restore the environment, as well as guarantee that such investments will not be restricted or undermined by local or international austerity policies. It is the responsibility of states to safeguard the rights of populations affected by these projects.

III. Protection of and Support for Peasant Agriculture and Food Sovereignty

- Implement comprehensive agrarian reforms that decentralise and democratise access to land, making it feasible for peasants to return to the countryside, and replace destructive agribusiness practices with agroecological production.

- Build and support mechanisms that spread and aid with the implementation of agroecology by providing technical assistance and financing for peasant farmers.

- Eliminate synthetic agrotoxins by 2035 and reduce synthetic fertilisers by half within the same period.

- Support the widespread use of bio-inputs for agroecological farming by creating bio-factories (community facilities that produce and reproduce natural inputs such as biofertilisers and biopesticides). Provide the necessary equipment for their use and guarantee free technical assistance for farmers.29

- Protect peasants’ rights to biodiverse seeds. Guarantee the intellectual property rights of Indigenous and traditional communities by combatting biopiracy and the appropriation of our knowledge and practices.

- Restructure livestock farming so that herd sizes and practices correspond to land capacity and food demand – not to the demands of the market.

- Ban all unproven agricultural technologies and eliminate all public subsidies for harmful practices and products.

- Adopt public policies that regulate and protect agricultural markets and the right to healthy, culturally appropriate food.

- Prioritise agroecological products in government food-purchasing programmes.

- Establish legislation to protect agroecological production zones, creating areas free from poisons, GMOs, and aerial spraying.

- Require governments to conduct studies that assess the need to rethink agricultural and livestock activities in response to global warming. This includes creating new agroclimatic maps and developing policies that protect biodiversity and ecosystem services.30

These studies must also involve, in a meaningful way, the communities rooted in each territory and draw on their culture and expertise.

- Ensure that technological products and processes used in rural areas are reassessed every five years, drawing on the participation of civil society representatives.

IV. Effective Policies for Reforestation and Combatting Deforestation

- Take all necessary measures to prevent the Amazon from reaching its point of no return, such as by protecting 80% of its territory by 2026.

- Halt all illegal deforestation by 2026.

- Achieve zero legal deforestation by 2027.

- Halt the expansion of the agricultural frontier by sanctioning companies and individuals responsible for land grabbing, displacing forest-dwelling peoples, and producing goods that drive deforestation, degradation, and pollution.

- Prohibit funds from the Paris Agreement from being channelled to agribusiness, mining, or false solutions like replanting and offset schemes in protected areas.

- Repeal legal instruments that promote the destruction of the Amazon.

- Rehabilitate, recover, and restore deforested and degraded areas.

- Ensure that all Indigenous, Afro-descendant, quilombola, and traditional communities in the Amazon are given titles to their ancestral lands as well as full legal and physical protection of their collective ownership of these lands.

- Guarantee respect for the territorial rights of isolated Indigenous peoples and implement a gender perspective in the distribution of land titles.

- Strengthen alternatives for an agroecological transition as well as community-based agroforestry production and ecotourism.

- Guarantee the meaningful participation of forest-dwelling peoples in every stage of the energy production chain – including planning, management, and governance – as part of building a just, popular, and comprehensive energy transition.

- Ban subsidies, investments, and financial credits for projects that destroy forests.

- Classify ecocide as a crime in national legislation and ensure the punishment of all environmental crimes.

- Prosecute corporations and companies responsible for environmental disasters in their countries of origin and require them to repair the damage done to nature and affected peoples.

- Promote financing for projects that protect the Amazon and other forests of the Global South, ensuring that all debt-for-climate or debt-for-nature swaps are: a) comprehensive, transparent, direct, and carried out with the participation of the peoples of the Amazon in ways that are self-determined, self-organised, and self-managed; b) embedded in current financing mechanisms with guaranteed participation, oversight, and social accountability to prevent abuse, waste, and corruption; and c) designed to ensure that nature is not commodified.

- Establish a carbon tax on major polluting industries and agribusinesses, directing the revenue toward protecting the Amazon and other forests of the Global South.

- Ban forest offsets and other forms of financial speculation and false market solutions in these territories.

- Require governments to implement large-scale reforestation projects, the countryside, and cities and to support the production and distribution of seedlings and the restoration of degraded areas.

V. Proper Planning and Management of Water Resources

- Use water efficiently, prioritising human and animal consumption and agroecological production over corporate interests.

- Manage aquatic systems to include the creation of protected areas that safeguard the health of river basins.

- Subsidise agroforestry, with an emphasis on food production in family farming units connected to food supply systems.

VI. Restrictions on Mining

- Immediately halt and combat illegal mining.

- Reduce mercury use in mining each year until it is fully eliminated.

- Ban mining in Indigenous, ancestral, and communal territories.

- Establish plans to restore areas degraded by mining.

- Implement remediation plans for ecosystems and communities affected by mercury and other mining impacts.

- Create monitoring systems and penalties for activities that compromise surface and groundwater quality.

Read full dossier : thetricontinental.org

Related posts:

Almost 2,000 land and environmental defenders were killed between 2012 and 2022 for simply standing up to protect our planet and us all from the accelerating climate crisis.

Almost 2,000 land and environmental defenders were killed between 2012 and 2022 for simply standing up to protect our planet and us all from the accelerating climate crisis.

African women unite on the frontlines of the Climate Crisis

African women unite on the frontlines of the Climate Crisis

UN warns over looming food crisis in Uganda

UN warns over looming food crisis in Uganda

The Deadly Toll of Land and Environmental Activism

The Deadly Toll of Land and Environmental Activism

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

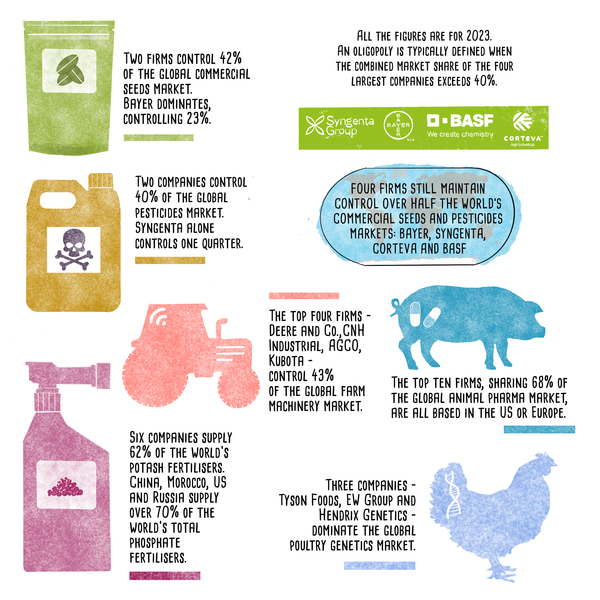

Top 10 agribusiness giants: corporate concentration in food & farming in 2025

Published

3 months agoon

August 28, 2025

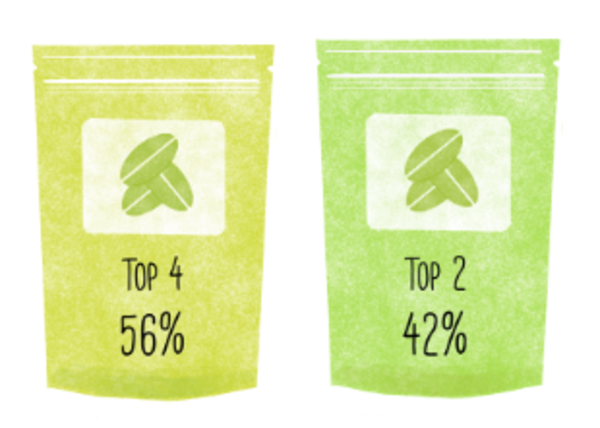

|

Ranking

|

Company (Headquarters)

|

Sales in 2023

(US$ millions)

|

% Global market share 19

|

|

1

|

Bayer (Germany)20

|

11,613

|

23

|

|

2

|

Corteva (US)21

|

9,472

|

19

|

|

3

|

Syngenta (China/Switzerland)22

|

4,751

|

10

|

|

4

|

BASF (Germany)23

|

2,122

|

4

|

|

Total top 4

|

27,958

|

56

|

|

|

5

|

Vilmorin & Cie (Groupe Limagrain) (France)24

|

1,984

|

4

|

|

6

|

KWS (Germany)25

|

1,815

|

4

|

|

7

|

DLF Seeds (Denmark)26

|

838

|

2

|

|

8

|

Sakata Seeds (Japan)27

|

649

|

1

|

|

9

|

Kaneko Seeds (Japan)28

|

451

|

0.9

|

|

Total top 9

|

33,695

|

67

|

|

|

Total world market29

|

50,000

|

100%

|

|

Ranking

|

Company (Headquarters)

|

Sales in 2023

(US$ millions)

|

% Global market share

|

|

1

|

Syngenta (China/Switzerland)43

|

20,066

|

25

|

|

2

|

Bayer (Germany)44

|

11,860

|

15

|

|

3

|

BASF (Germany)45

|

8,793

|

11

|

|

4

|

Corteva (US)46

|

7,754

|

10

|

|

Total top 4

|

48,472

|

61

|

|

|

5

|

UPL (India)47

|

5,925

|

8

|

|

6

|

FMC (Germany)48

|

4,487

|

6

|

|

7

|

Sumitomo (Japan)49

|

3,824

|

5

|

|

8

|

Nufarm (Australia)50

|

2,056

|

3

|

|

9

|

Rainbow Agro (China)51

|

1,623

|

2

|

|

10

|

Jiangsu Yangnong Chemical Co., Ltd. (China)52

|

1,595

|

2

|

|

Total top 10

|

67,982

|

86

|

|

|

Total world market53

|

79,000

|

100

|

|

Ranking

|

Company (Headquarters)

|

Sales in 2023

(US$ millions)

|

% Global market share

|

|

1

|

Nutrien (Canada)72

|

15,673

|

8

|

|

2

|

The Mosaic Company (US)73

|

12,782

|

7

|

|

3

|

Yara (Norway)74

|

11,688

|

6

|

|

4

|

CF Industries Holdings, Inc, (US)75

|

6,631

|

3

|

|

Total top 4

|

46,774

|

24

|

|

|

5

|

ICL Group Ltd. (Israel)76

|

6,294

|

3

|

|

6

|

OCP (Morocco)77

|

5,967

|

3

|

|

7

|

PhosAgro (Russia)78

|

4,989

|

3

|

|

8

|

MCC EuroChem Joint Stock Company (EuroChem) (Switzerland/Russia)79

|

4,298

|

2

|

|

9

|

OCI (Netherlands)80

|

4,188

|

2

|

|

10

|

Uralkali (Russia)81

|

3,497

|

2

|

|

Total top 10

|

76,007

|

39

|

|

|

Total world market82

|

196,000

|

100

|

|

Ranking

|

Company (Headquarters)

|

Sales in 2023

(US$ millions)

|

% Global market share

|

|

1

|

Deere and Co. (US)89

|

26,790

|

15

|

|

2

|

CNH Industrial (UK/Netherlands)90

|

18,148

|

10

|

|

4

|

AGCO (US)91

|

14,412

|

8

|

|

3

|

Kubota (Japan)92

|

14,233

|

8

|

|

Total top 4

|

73,583

|

43

|

|

|

5

|

CLAAS (Germany)93

|

6,561

|

4

|

|

6

|

Mahindra and Mahindra (India)94

|

3,156

|

2

|

|

7

|

SDF Group (Italy)95

|

2,197

|

1

|

|

8

|

Kuhn Group (Switzerland)96

|

1,583

|

0.9

|

|

9

|

YTO Group (China)97

|

1,493

|

0.9

|

|

10

|

Iseki Group (Japan)98

|

1,057

|

0.6

|

|

Total top 10

|

89,629

|

52

|

|

|

Total world market99

|

173,000

|

100

|

|

Ranking

|

Company (Headquarters)

|

Sales in 2023

(US$ millions)

|

% Global market share

|

|

1

|

Zoetis (US)115

|

8,544

|

18

|

|

2

|

Merck & Co (MSD) (US)116

|

5,625

|

12

|

|

3

|

Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health (Germany)117

|

5,100

|

11

|

|

4

|

Elanco (US)118

|

4,417

|

9

|

|

Total top 4

|

23,686

|

49

|

|

|

5

|

Idexx Laboratories (US)119

|

3,474

|

7

|

|

6

|

Ceva Santé Animale (France)120

|

1,752

|

4

|

|

7

|

Virbac (France)121

|

1,348

|

3

|

|

8

|

Phibro Animal Health Corporation (US)122

|

978

|

2

|

|

9

|

Dechra (UK)123

|

917

|

2

|

|

10

|

Vetoquinol (France)124

|

572

|

1

|

|

Total top 10

|

32,727

|

68

|

|

|

Total world market125

|

48,000

|

100

|

The genetic material used in the industrial production of meat, dairy and aquaculture is supplied by a small number of relatively unknown companies that are mostly privately owned. As detailed financial data is not publicly available for most of these companies, it is difficult to determine companies’ market shares and even the value of the global market. However, it was possible to arrive at some estimates for chicken, which tops global meat production (narrowly exceeding pigs).126

The genetic material used in the industrial production of meat, dairy and aquaculture is supplied by a small number of relatively unknown companies that are mostly privately owned. As detailed financial data is not publicly available for most of these companies, it is difficult to determine companies’ market shares and even the value of the global market. However, it was possible to arrive at some estimates for chicken, which tops global meat production (narrowly exceeding pigs).126Related posts:

CORPORATE AGRIBUSINESS GIANTS SWIM IN WEALTH AS MORE POOR PEOPLE GO HUNGRY AMID THE BITING COVID PANDEMIC.

CORPORATE AGRIBUSINESS GIANTS SWIM IN WEALTH AS MORE POOR PEOPLE GO HUNGRY AMID THE BITING COVID PANDEMIC.

A corporate cartel fertilises food inflation

A corporate cartel fertilises food inflation

The United Nations Food Systems Summit is a corporate food summit —not a “people’s” food summit

The United Nations Food Systems Summit is a corporate food summit —not a “people’s” food summit

Food inflation: The math doesn’t add up without factoring in corporate power

Food inflation: The math doesn’t add up without factoring in corporate power

EALA members renew push for unified sub-regional Agroecology Law during Mukono meeting.

East African lawmakers and CSO leaders are meeting in Uganda to draw up plans to promote Agroecology as an alternative to climate change mitigation.

Kenyan farmers secure right to share local seeds in court ruling

Land for over 1000 families claimed to be a forest reserve and grabbed by NFA is now used for cattle keeping under heavy Army guardship – Witness Radio.

Happening shortly! Kenya’s upcoming court ruling on the Seed Law could have a significant impact on farmers’ rights, food sovereignty, and the country’s food system.

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

“Vacant Land” Narrative Fuels Dispossession and Ecological Crisis in Africa – New report.

Report reveals ongoing Human Rights Abuses and environmental destruction by the Chinese oil company CNOOC

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

- PRESENDIANTIAL DIRECTIVE BANNING ALL LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoHappening shortly! Kenya’s upcoming court ruling on the Seed Law could have a significant impact on farmers’ rights, food sovereignty, and the country’s food system.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoActivists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days agoEast African lawmakers and CSO leaders are meeting in Uganda to draw up plans to promote Agroecology as an alternative to climate change mitigation.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days agoKenyan farmers secure right to share local seeds in court ruling

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoEnvironmentalists reject TFFF, warning it will deepen forest destruction.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days agoEALA members renew push for unified sub-regional Agroecology Law during Mukono meeting.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days agoLand for over 1000 families claimed to be a forest reserve and grabbed by NFA is now used for cattle keeping under heavy Army guardship – Witness Radio.

-

STATEMENTS6 days ago

STATEMENTS6 days agoJoint Statement Response by Advisers of PAPs to the DRS Follow-Up Report on the Uganda KIIDP-2 Case