SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

International Finance Corporation Should Stop Bankrolling Destructive Agribusiness

Published

3 years agoon

In late June, the World Bank’s private sector arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), approved a US$200M loan to agribusiness giant Louis Dreyfus Company (LDC). Under the guise of “sustainable development,” the loan will be used to purchase soy and corn—mostly destined for factory farms—grown on industrial mega-farms in Brazil’s heavily threatened Cerrado.

A biodiversity hotspot that is home to 5 percent of the world’s animals and plants and 216 Indigenous territories, the Cerrado has already lost half its native vegetation to cattle ranches and mechanized soy and corn mega-farms. LDC is just one of many agribusinesses, including Cargill, Bunge, JBS, and Marfrig, whose beef and animal feed operations are threatening to drive this ecosystem towards total destruction by 2030.

While IFC claims that its loan to LDC will “address higher demand and escalating food prices in an environmentally sustainable and socially inclusive way,” in reality, this investment will drive further environmental destruction and disenfranchisement of local and indigenous communities while enriching one of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful industrial agribusinesses. In 2020, LDC generated US$49 billion in revenue and has US$3.5 billion in public and private financing available. With limited public investment in sustainable agriculture, one must ask why taxpayer funds are being used to support this well-resourced mega-corporation that has contributed to Cerrado ecosystem destruction over the past decade.

Since late May, Friends of the Earth, members of the Stop Financing Factory Farming (SFFF) Campaign and 230+ civil society organizations (CSOs) from around the world have fought to block the investment. In numerous letters to the IFC and its government shareholders, groups documented how this investment is at odds with the bank’s own environmental policies and its commitment to align lending with the Paris Agreement and United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Supporting industrial animal feed production does not advance the UN Sustainable Development Goals

The IFC justified its US$200 million loan by claiming that the funds would help to reduce deforestation through “support [for] a portfolio of eligible soy and corn farmers in Brazil that are committed to zero deforestation and conversion of native vegetation.” But these “eligible farmers” are multi-thousand-acre industrial operations located in the states of Goiás, Mato Grosso, and Minas Gerais, which are already largely deforested. Even if incentives set up under the loan could prevent future land conversions, deforestation is only one of the many environmental and social impacts that should be addressed by public financing for a company like LDC.

Completely ignored in IFC’s loan analysis are the additional negative impacts of industrial farms’ use of pesticides and fertilizers on climate and air, soil and water resources. Also ignored were harmful social impacts of these operations, including pesticide-related illness and death, including among children, as well as the potential for land-grabbing, local community conflicts and the displacement of smallholder farmers.

Failure to address these serious issues undermines the IFC’s stated commitment to help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. A 2019 German government report documents how large-scale soy operations in the Cerrado and elsewhere “are associated with social injustice and…environmental degradation that hinders the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).” According to this report, agribusiness operations in the region threaten at least 8 of the 17 SDGs, including: 1: No Poverty, 2: Zero Hunger, 3: Good Health and Well-Being, 12: Responsible Consumption and Production and 13: Climate Action.

A coherent strategy to make LDC’s soy and corn operations more “sustainable” would have required a shift in agricultural practices that reduce fossil fuel, pesticide and synthetic fertilizer use, as CSOs explained. A more “inclusive” and food security-centered strategy would ensure at least some support for smallholder, lower-carbon, regenerative crop systems and increased land access for traditional communities.

Diverting resources to feed animals instead of humans also threatens to aggravate the current global hunger crisis. As the crisis intensifies, the world’s 800 million+ hungry people would be better served by public development banks using taxpayer funds to support the production of diversified, truly sustainable and nutritious food rather than feed for factory farms that churn out cheap meat and dairy products for consumption in higher-income countries.

Paris Agreement misalignment: LDC is a major laggard on climate

The IFC’s support for a company that has failed to set sufficient GHG reduction targets is at odds with the bank’s commitment to aligning its investments with the Paris Agreement.

Unlike some of its peers, LDC has yet to set Paris-aligned reduction targets for its GHG emissions. The company has committed to only meager 1 percent reductions in its Scope 1 and 2 emissions (those generated by the operations or activities the company controls). Even more important, LDC has yet to calculate its Scope 3 emissions (those generated by operations or activities a company does not control, including soy production), which likely make up more than 90 percent of the company total. At a minimum, the IFC and other public development banks should require any company benefiting from its preferential financing to set Paris-aligned GHG reduction targets.

Now that the LDC loan has been approved, IFC must be held accountable for its impacts

Together with global allies and partners on the ground in Brazil, the Stop Financing Factory Farming Campaign will continue to track LDC’s activities and demand accountability from the IFC for the harmful impacts of its lending. In a letter responding to the loan approval, more than 100 organizations have asked that the IFC disclose the names and locations of the industrial operations its funds will support so that groups on the ground can monitor the impacts of its investment. We have also asked that the IFC urge LDC to cut ties with suppliers known to be involved in illegal deforestation, land grabbing and/or other human rights violations.

The campaign will also continue to urge the IFC and its government shareholders to shift lending away from industrial livestock and monoculture feed production and toward smallholder, lower-carbon regenerative mixed crop systems. Such a shift would square with the World Bank’s own guidance concerning development banks’ role in encouraging capital investments that “incentivize more sustainable practices—properly valuing ecosystem services and mobilizing resources, knowledge and technology for smallholders, indigenous peoples and other producers to support a more equitable way of producing and consuming food.”

Source: FoodTank

Related posts:

Agribusiness and big finance’s dirty alliance is anything but “green”

Agribusiness and big finance’s dirty alliance is anything but “green”

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

UN seeks increased public finance to protect forests.

UN seeks increased public finance to protect forests.

Masindi High Court to rule on an interim application seeking to stop a multi-million agribusiness company from an illegal and forceful eviction.

Masindi High Court to rule on an interim application seeking to stop a multi-million agribusiness company from an illegal and forceful eviction.

You may like

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

Published

1 day agoon

July 8, 2025

Special report by the dedicated and thorough Witness Radio team, offering a comprehensive and in-depth overview of the situation.

As Uganda moves forward with the controversial East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), a wave of arrests, intimidation, and court cases has targeted youth and environmental activists opposing the project. However, there is a noticeable and encouraging shift within Uganda’s justice systems, with a growing support for the protesters, potentially signaling a change in the legal landscape.

The EACOP project, stretching 1,443 kilometers from Uganda to Tanzania, has been hailed by the government as a development milestone. However, human rights groups and environmental watchdogs have consistently warned that the project poses serious risks to communities, biodiversity, and the climate. Concerns over land grabbing, inadequate compensation, and ecological degradation have mobilized a new generation of Ugandan activists.

Since 2022, as opposition to EACOP grew louder, Ugandan authorities have intensified a campaign of arrests and legal harassment. Police, military, and currently the Special Forces Command, a security unit tasked with protecting Uganda’s president, have been involved in brutal crackdowns on these activists.

Yuda Kaye, the mobilizer for students against EACOP, believes the criminalization is an attempt by the government to weaken their cause and silence them from speaking out about the project’s negative impacts.

“We are arrested just for raising the project concerns, which affect our future, the local communities, and the environment at large. Oftentimes, we are arrested without reason. They just round us up at once and brutally arrest us, Mr. Kaye reveals, in an interview with Witness Radio’s research team.

Activists have faced a litany of charges, including unlawful assembly, incitement to violence, public nuisance, and criminal trespass. Many of these charges have lacked substantive evidence and have been dismissed by the courts or had their files closed by the police after prolonged delays.

A case review conducted by Witness Radio Uganda reveals that Uganda’s justice system is being used to suppress the activities of youth activists opposing the project, rather than convicting them. However, despite the system being used to silence them, it has often found no merit in these cases.

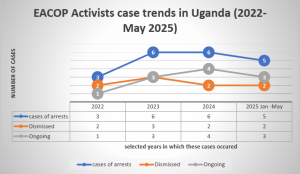

Of a sample of 20 documented cases since 2022 involving the arrest of over 180 activists, 9 case files against the activists have either been dismissed by courts or closed by the police due to a lack of prosecution, another signal indicating the relevance of their work, while 11 cases remain ongoing.

The chart below shows trends in arrests, dismissed cases, and ongoing cases involving EACOP activists in Uganda from 2022 to May 2025.

The review was conducted with support from the activists themselves and their lawyers. It involved a desk review and analysis of Witness Radio articles concerning the arrests of defenders and activists opposing the EACOP project.

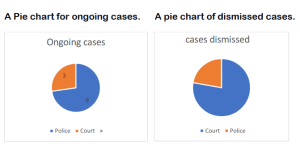

Witness Radio’s analysis reveals a concerning trend as the majority of cases involving these activists are stalling at the police level rather than progressing to the courts of law. This suggests that the police have not only criminalized activism but are also playing a syndicate role in deliberately prolonging these cases under the excuse of ongoing investigations.

“While both the police and judiciary are being used to suppress dissent, the courts have at least demonstrated a degree of fairness, having dismissed at least 78% of cases that fall within their jurisdiction. In contrast, the police continue to hold 73% of activist cases in limbo, citing investigations as justification for indefinite delays.” The research team discovered.

Witness Radio’s analysis further shows that in most of these cases, the state has failed to produce witnesses or evidence to convict the activists, adding that the charges are often just tools of intimidation. Additionally, this is accompanied by more extended periods during which decisions are being made.

Despite the intense crackdown, it is evident that these activists are winning, as no proven record of sentencing has been observed. Instead, these cases are often marred by delays in court or at the police, and in the end, some have been dismissed. This implies that protest marches and petition deliveries serve a purpose; the state just needs to listen to their concerns and formulate possible solutions to address them,” said Tonny Katende, Witness Radio Uganda’s Research, Media and Documentation Officer.

According to Article 29(1)(d) of the Constitution of Uganda, every individual has the right to “assemble and demonstrate together with others peacefully and unarmed and to petition.” Additionally, Article 20 emphasizes that fundamental rights and freedoms “are inherent and not granted by the State.” Yet activists report that police regularly deny them the right to exercise their rights as guaranteed.

At a February 2025 press conference, EACOP activists strongly condemned the police’s continued unlawful arrests of demonstrators exercising their constitutional rights and case delays. This followed escalating crackdowns that added to the tally of over 100 activists arrested in 2024 alone.

“We strongly condemn these arrests. Detaining demonstrators does not address the concerns affecting grassroots communities impacted by oil and gas projects,” declared the group, led by Bob Barigye, who remains in prison on another charge still linked to his opposition to EACOP.

An interview with Mr. Yuda Kaye, a mobilizer from the Students Against EACOP Movement, confirmed that the ongoing dismissals only reaffirm the legitimacy of their resistance.

“These cases are dismissed because the government and its justice systems don’t have any grounds to convict us. This justifies the fact that the issues we’re discussing are real. We only seek accountability, but since the government has power, they criminalize us and silence us,” Mr. Kaye added.

According to Kaye, the intimidation is real, but so is their commitment. “We are called enemies of progress, but we’re only protecting our future and that of our country. We’ve often proposed alternatives, but the government doesn’t want them.” He re-echoes.

Despite this, activists say their rights are routinely violated. Witness Radio Uganda attempted to contact the police spokesperson, Mr. Kituuma Rusooke, but known numbers were unreachable, and messages sent to him went unanswered.

In a separate interview with Mr. James Eremye Mawanda, the Judiciary Spokesperson, he acknowledged the pattern of dismissals and delays.

“As the Judiciary, we listen to cases, and where there is no evidence to support the case, a decision is made. When a crime is allegedly committed and an individual is brought before the court, the courts upholding the rule of law shall administer justice,” he said.

According to Witness Radio’s analysis, 2025 has seen the most dismissals so far, with six cases concluding, reinforcing the view that criminalization is used more for intimidation than as a means of legal redress. “Whereas the arrests took place in separate years, most of the dismissals have happened in 2025,” the research team further highlighted.

Mr. Brighton Aryampa, the team lead of Youth for Green Communities, one of the organizations that provide legal representation for Stop-EACOP activists, highlighted that the criminalization of Ugandan activists undermines Uganda’s democratic principles of free expression and open discourse.

“The government, in bed with oil corporations Total Energies and CNOOC, is deliberating using legal action against Stop EACOP activists to suppress dissent, free speech, right to peaceful protest, and against public participation. This is tainting Uganda as a country that undermines the democratic principles of free expression and open discourse, as hundreds of Stop EACOP activists have been arrested, charged, and some tried by a competent court. However, no one has been found guilty of the fabricated offense usually slapped on them.” He said in an interview with Witness Radio.

Counsel Aryampa further advised that the practice of powerful companies and businesses blackmailing and corrupting the Ugandan government to develop harmful projects while ignoring all social warnings and human rights abuses must be stopped.

The pressure exerted by these activists, both locally and internationally, has slowed the EACOP project. It has also led to bankers and insurers withdrawing from financing or insuring the project. According to Stop EACOP campaigners, more than 40 international banks and 30 global insurance firms, including Chubb, have distanced themselves from the controversial pipeline project, citing human rights and climate concerns raised by these activists.

Meanwhile, as the activism grows, the number of arrests is rising. Within just the first six months of 2025, over 40 activists have been criminalized for their activism. Among them is KCB 11, a group of eleven activists that was arrested at the KCB offices in April 2025. The group has spent over two months on remand, despite their lawyers’ pleas for bail to be granted.

Related posts:

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

EACOP activism under Siege: Activists are reportedly criminalized for opposing oil pipeline project in Uganda.

EACOP: The trial of 20 environmental activists failed to take off, and now they want the case dismissed for lack of prosecution.

EACOP: The trial of 20 environmental activists failed to take off, and now they want the case dismissed for lack of prosecution.

Milestone: Another case against the EACOP activists is dismissed due to the want of prosecution.

Milestone: Another case against the EACOP activists is dismissed due to the want of prosecution.

The latest: Another group of anti-EACOP activists has been arrested for protesting Stanbic Bank’s financing of the EACOP Project.

The latest: Another group of anti-EACOP activists has been arrested for protesting Stanbic Bank’s financing of the EACOP Project.

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

‘Left to suffer’: Kenyan villagers take on Bamburi Cement over assaults, dog attacks

Published

4 months agoon

March 22, 2025

- The victims are aged between 24 and 60, and one of them has since passed on.

- Many were severely injured and hospitalized following brutal attacks, unlawful detention, and physical assault by Bamburi’s security personnel.

Editor’s note: Read the petition here.

Their hopes for justice seemed to be slipping away after initially taking on a multinational corporation and failing to hold it accountable for the brutal injuries they suffered.

The death of one of their own cast a shadow of despair, making it seem unlikely that they would ever bring the corporation to justice for the crimes they alleged.

However, 11 victims of dog attacks, assaults, and other severe human rights violations are now challenging Bamburi Cement PLC’s role in these abuses in court.

They are represented by the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC), which on January 29, 2025, filed a legal claim before a constitutional court in Kenya, seeking to hold the multinational accountable for the harm suffered by the victims—residents of land parcels in Kwale that Bamburi claims ownership of. KHRC worked with the Kwale Mining Alliance (KMA) to bring this case.

The victims, aged between 24 and 60, include Mohamed Salim Mwakongoa, Ali Said, Abdalla Suleiman, Hamadi Jumadari, Abdalla Mohammed, and Omari Mbwana Bahakanda. Others are Shee Said Mbimbi, Omar Mohamed, Omar Ali Kalendi (deceased), Abdalla Jumadari, and Bakari Nuri Kassim.

Bamburi had hired a private security firm and deployed General Service Unit (GSU) officers to guard three adjoining land parcels, covering approximately 1,400 acres in Denyenye, Kwale. The GSU established a camp on the land, which has historically been accessed by residents who have long used established routes to reach the forest and the Indian Ocean.

For decades, these routes provided them with access to resources such as firewood, crops, and fish, which they relied on for their livelihoods. However, five years ago, when they attempted to collect firewood, harvest crops, and access the ocean through the land, Bamburi accused them of trespassing. The company’s private guards and GSU officers responded with force, setting dogs on them and assaulting them.

Many were severely injured and hospitalized following brutal attacks, unlawful detention, and physical assault by Bamburi’s security personnel. These incidents occurred despite the lack of clearly defined boundaries and the fact that the traditional access routes had never been contested.

According to the petition, GSU officers and private guards inflicted serious injuries by kicking, punching, and beating the victims with batons. Those who were arrested were neither taken to a police station nor charged with any offense. Despite their injuries, they were denied emergency medical care.

These actions were intended to intimidate residents, prevent them from accessing the beach, and suppress any historical claims to the land, the victims tell the court. Local police in Kwale failed to investigate the abuses, visit the crime scenes, or arrest any of the perpetrators, they add.

Now, the victims are seeking compensation for these violations. They have also asked the court to declare that their rights were violated through torture inflicted by Bamburi’s guards and GSU officers. Additionally, they want the court to rule that releasing guard dogs to attack them during arrests constituted an extreme and unlawful use of force.

Source: khrc.or.ke

Related posts:

Breaking: Over 600 attacks against defenders have been recorded in the year 2023 globally- BHRRC report.

Breaking: Over 600 attacks against defenders have been recorded in the year 2023 globally- BHRRC report.

Kaweeri Coffee land grabbing case re-trial resumes as evictees continue to suffer gross human rights violations.

Kaweeri Coffee land grabbing case re-trial resumes as evictees continue to suffer gross human rights violations.

Criminalization of planet, land, and environmental defenders in Uganda is on the increase as 2023 recorded the soaring number of attacks.

Criminalization of planet, land, and environmental defenders in Uganda is on the increase as 2023 recorded the soaring number of attacks.

Local land grabbers evict villagers at night; foreign investors cultivate the same lands the next day

Local land grabbers evict villagers at night; foreign investors cultivate the same lands the next day

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

River ‘dies’ after massive acidic waste spill at Chinese-owned copper mine

Published

4 months agoon

March 22, 2025A catastrophic acid spill from a Chinese-owned copper mine in Zambia has contaminated a major river, sparking fears of long-term environmental damage and potential harm to millions of people.

The spill, which occurred on February 18, has sent shockwaves through the southern African nation.

Investigators from the Engineering Institution of Zambia revealed that the incident stemmed from the collapse of a tailings dam at the mine.

This dam, designed to contain acidic waste, released an estimated 50 million litres of toxic material into a stream feeding the Kafue River, Zambia’s most important waterway.

The waste is a dangerous cocktail of concentrated acid, dissolved solids, and heavy metals.

The Kafue River, stretching over 930 miles (1,500 kilometres) through the heart of Zambia, supports a vast ecosystem and provides water for millions. The contamination has already been detected at least 60 miles downstream from the spill site, raising serious concerns about the long-term impact on both human populations and wildlife.

Environmental activist Chilekwa Mumba, working in Zambia’s Copperbelt Province, described the incident as “an environmental disaster really of catastrophic consequences”.

The spill underscores the risks associated with mining, particularly in a region where China holds significant influence over the copper industry.

Zambia ranks among the world’s top 10 copper producers, a metal crucial for manufacturing smartphones and other technologies.

Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema has appealed for expert assistance to address the crisis. The full extent of the environmental damage is still being assessed.

A river died overnight

An Associated Press reporter visited parts of the Kafue River, where dead fish could be seen washing up on the banks about 60 miles downstream from the mine run by Sino-Metals Leach Zambia, which is majority owned by the state-run China Nonferrous Metals Industry Group.

The Ministry of Water Development and Sanitation said the “devastating consequences” also included the destruction of crops along the river’s banks. Authorities are concerned that ground water will be contaminated as the mining waste seeps into the earth or is carried to other areas.

“Prior to February 18 this was a vibrant and alive river,” said Sean Cornelius, who lives near the Kafue and said fish died and birdlife near him disappeared almost immediately.

“Now everything is dead, it’s like a totally dead river. Unbelievable. Overnight, this river died.”

About 60 per cent of Zambia’s 20 million people live in the Kafue River basin and depend on it in some way as a source of fishing, irrigation for agriculture and water for industry. The river supplies drinking water to about five million people, including in the capital, Lusaka.

The acid leak at the mine caused a complete shutdown of the water supply to the nearby city of Kitwe, home to an estimated 700,000 people.

Attempts to roll back the damage

The Zambian government has deployed the air force to drop hundreds of tons of lime into the river in an attempt to counteract the acid and roll back the damage. Speed boats have also been used to ride up and down the river, applying lime.

Government spokesperson Cornelius Mweetwa said the situation was very serious and Sino-Metals Leach Zambia would bear the costs of the cleanup operation.

Zhang Peiwen, the chairman of Sino-Metals Leach Zambia, met with government ministers this week and apologized for the acid spill, according to a transcript of his speech at the meeting released by his company.

“This disaster has rung a big alarm for Sino-Metals Leach and the mining industry,” he said.

It “will go all out to restore the affected environment as quickly as possible”, he said.

Discontent with Chinese presence

The environmental impact of China’s large mining interests in mineral-rich parts of Africa, which include Zambia’s neighbors Congo and Zimbabwe, has often been criticised, even as the minerals are crucial to the countries’ economies.

Chinese-owned copper mines have been accused of ignoring safety, labour and other regulations in Zambia as they strive to control its supply of the critical mineral, leading to some discontent with their presence.

Zambia is also burdened with more than $4 billion in debt to China and had to restructure some of its loans from China and other nations after defaulting on repayments in 2020.

A smaller acid waste leak from another Chinese-owned mine in Zambia’s copper belt was discovered days after the Sino-Metals accident, and authorities have accused the smaller mine of attempting to hide it.

Local police said a mine worker died at that second mine after falling into acid and alleged that the mine continued to operate after being instructed to stop its operations by authorities. Two Chinese mine managers have been arrested, police said.

Both mines have now halted their operations after orders from Zambian authorities, while many Zambians are angry.

“It really just brings out the negligence that some investors actually have when it comes to environmental protection,” said Mweene Himwinga, an environmental engineer who attended the meeting involving Mr Zhang, government ministers, and others.

“They don’t seem to have any concern at all, any regard at all. And I think it’s really worrying because at the end of the day, we as Zambian people, (it’s) the only land we have.”

Source: www.independent.co.uk

Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

A decade of displacement: How Uganda’s Oil refinery victims are dying before realizing justice as EACOP secures financial backing to further significant environmental harm.

Carbon Markets Are Not the Solution: The Failed Relaunch of Emission Trading and the Clean Development Mechanism

A decade of displacement: How Uganda’s Oil refinery victims are dying before realizing justice as EACOP secures financial backing to further significant environmental harm.

Govt launches Central Account for Busuulu to protect tenants from evictions

Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

Despite harsh repression, opposition to the EACOP pipeline in Uganda remains strong

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

- PRESENDIANTIAL DIRECTIVE BANNING ALL LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA

- FROM LAND GRABBERS TO CARBON COWBOYS A NEW SCRAMBLE FOR COMMUNITY LANDS TAKES OFF

- African Faith Leaders Demand Reparations From The Gates Foundation.

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS1 day ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS1 day agoActivism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

-

NGO WORK1 week ago

NGO WORK1 week agoCommunities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania