SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

A Century of Agro-Colonialism in the DR Congo

Published

4 years agoon

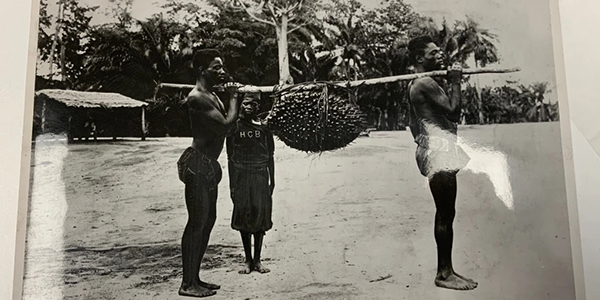

Plantation workers holding a bunch palm oil fruit. The photo was taken in the Belgian colony of Congo, probably in the 1930s or 1940s.

Many oil palm plantations’ concessions in West and Central Africa were built on lands stolen from communities during colonial occupations. This is the case in the DRC, where food company Unilever began its palm oil empire. Today, these plantations are still sites of on-going poverty and violence. It is time to end the colonial model of concessions and return the land to its original owners.

Many of the oil palm plantations now owned by multinational corporations in West and Central Africa were built on lands stolen from local communities during colonial occupations. This is the case in what is known today as the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where the Anglo-Dutch multinational food company Unilever began building its palm oil empire. Today, these plantations are sites of on-going poverty, conflict and violence. There can be no solution to these problems until lands are returned to the communities and justice is realised for the harms that have endured.

In 1911, King Leopold of Belgium granted the British industrialist Lord Leverhulme vast concessions over lands that are within what is now the DRC. These forested areas, twice the area of Belgium, were full of oil palm groves, that the local inhabitants had cared for and developed over generations, converting what was once a savannah into one of the world’s most important tropical forests.

Leverhulme wanted a cheap source of vegetable oil for his company’s leading brand of detergent, Sunlight– and he wasn’t the only one turning to the people of the Congo for it. Palm oil, long an important part of food systems in Central Africa, was of growing interest to European traders, especially Portuguese traders who by then were regularly visiting communities along the Congo River to purchase palm nuts. The competition was increasing local prices for the nuts, much to the displeasure of Leverhulme. (1)

The concessions did not give Leverhulme’s company, Huileries du Congo Belge (HCB), rights over the territories of local communities living within the concession, and there was supposed to be a process to demarcate the lands within the concessions. But Leverhulme was impatient and he pushed the Belgian authorities to grant him a monopoly over the purchase of nuts in the area– under infamous “tripartite agreements” between Leverhulme, the Belgian colonial authority and local communities, who in reality had no say over the matter. From then on, locals were treated as thieves if they dared to supply nuts harvested from their own palm groves to anyone other than Leverhulme’s company– even though the open market price was generally three to four times higher than that paid by Leverhulme.

In 1924, Portuguese traders active in the area of Basoko, in today’s Tshopo province, sent a letter to the Belgium colonial authority decrying the agreements:

“This contract concluded on 5th July last prohibits anyone purchasing in whatsoever fashion products deriving from the [oil] palm, be it nuts, kernels or oil, in the concession granted to this company [HCB], and what is still more detrimental to our interests, this measure also covers products harvested on land occupied by the natives…. The natives have strictly defined rights over the fields and plantations, and over the products harvested there. How then could it be acceptable for them to be forced to surrender their palm produce to just one company? Does this obligation not deprive them of the benefit of competition? What authorised representatives of the natives could ever have concluded, in their own name, a contract which brings them only disadvantages?” (2)

Leverhulme and the Belgian colonialists justified this scandalous monopoly on the grounds that Leverhulme’s company was making significant investments in the area by building palm oil mills and providing the locals with jobs, schools, medical clinics and churches. They also concocted, without any scientific basis, an argument that the palm groves were “natural” and not, as was widely known to locals and foreigners who spent time in the area, that the palm groves were the result of generations of care and work by local communities. If the palm groves were “natural'”, the State (i.e. the Belgian colonial authority) could thus claim dominion over them and more easily justify handing control over them to Leverhulme’s company.

Neither argument held any weight. The schools that the company established were of poor quality and largely unattended by local children, who were busy labouring for the company anyways. The company’s medical services were equally inaccessible to local villagers, and as one colonial administrator admitted: “Even in the most favourable circumstances, it is still doubtful whether the benefits of medicine offset all the ills that exploitation of the palm groves causes the population … The compulsory labour is generally too onerous … The time devoted to collecting and transporting the fruit is often excessive, and the contribution made by the women and the children often puts impossible demands upon their physical strength.” The annual mortality rate around the Leverhulme’s Huileries du Congo Belge operations was said to be at a “murderous” 10 per cent. (3)

Moreover, the employment provided by the company was in reality forced labour. In a letter from 1925, a district commissioner from Basoko wrote to the provincial governor about the labour situation at Leverhulme’s operations:

“Recruitment of workers for the HCB has been for many years so unpopular with the natives that the moral pressure exerted by the territorial administrators barely prevails … The whole of Aruwini district is rich, and a worker gathering natural produce of the forest (palm nuts especially) may readily earn a living and create resources not available to him through labour in industry or trade … The only way to effect an easy transition between [forced] labour and free waged labour would be to pay the worker a wage that is at least equal to what he can earn without leaving his village or changing his habits. The only firm established in the district [the HCB] offers its workers a wage that in no way compensates them for their sacrifices.” (4)

When it came to the palm groves, it was clear to anyone who had spent a minimum of time in the area that these groves were created from the labour and care of the local communities. The Belgian agronomist and missionary Hyacinthe Vanderyst, who spent years studying the palm groves in the Congo, published an article in the Belgian periodical Congo in 1925, in which he wrote:

“All of my own observations, researches and studies confirm in the most positive and absolute fashion the argument espoused by the natives… Conversely no one has so far openly attempted to prove that the palm groves are natural formations. This is no more than an assertion, wholly lacking supporting arguments … The natives declare themselves to be the owners of the palm groves, and perhaps secondary forests, and this on several grounds: on the grounds that they were the original occupants of the country in terms of stable settlements, hunting, fishing and the harvesting of natural products; on the grounds that they were farmers who cleared and exploited the savannahs, which were thereby turned into forests, and later into palm groves; on the grounds that they were creators of palm groves thanks to their direct and deliberate intervention, which had involved introducing the oil palm into the country… For what reasons does the State deny these grounds, or refuse to take them into account?”

Vanderyst then warned his Belgian audience, “The question of the palm groves, if it is not resolved according to native customs, will remain open forever, because of its great material significance.” (5)

Leverhulme and the Belgian colonial authorities ignored his advice. A few years later, the two sides moved forward with plans to demarcate more clearly HCB’s lands, and enclose the local populations in their villages. Here is how one HCB managing director described the arrangement in a letter to the governor of Equateur Province in 1928:

“They [the natives] will be forbidden to move their villages and their cultivated fields outside the boundaries assigned to them, and they will be forbidden to gather fruit from palms on our land without rendering themselves liable to persecution … They should remain confined to their reservations. … We shall not allow them to take palm fruit from palms growing on our own concessions, in order simply to sell them to other traders; and if they engage in acts of violence against our workers or against our European agents– as they have threatened to do– we shall invoke the protection from the state guaranteed us by article 18 of our Convention.” (6)

The ‘Pende rebellion’ of 1931 – in reference to the Pende People living in the southwest of what is today DR Congo – was one of the biggest rebellions during the Belgian colonial occupation. It started in the Kwango district, in particular in the territories of Kikwit and Kandale, areas dominated by HCB’s palm oil operations, and one other company called Compagnie de Kasaí. One of the major reasons, if not the main reason, for the rebellion was the brutal policy of the colonial administration in the area, which, due to a lack of workforce for the oil palm activities, sent soldiers to the villages to violently recruit workers. The mortality among those recruited was extremely high: for every 20 workers recruited to collect oil palm fruit in and around Lusanga – the center of HCB’s oil palm operations in the region – hardly 10 returned to their villages. The economic crisis of the early 1930s further reduced the wages of workers and led the colonisers to increase taxes, which worsened the overall situation. An estimated 500 villagers were killed in clashes with the colonial army during the rebellion, and hundreds more perished in camps where they were imprisoned under brutal conditions. (7)

From colonial occupation to finance capitalism

Leverhulme’s company, which would later morph into the Anglo-Dutch multinational food giant, Unilever, eventually converted large chunks of its concessions into industrial oil palm plantations and stopped sourcing palm nuts from the remaining local palm groves. Over hundreds of thousands of hectares in various parts of the Congo, HCB implemented a racist and violent occupation of community lands according to the plan that its managing director described in 1928. For the affected communities, little changed as far as labour conditions, access to land and forests or the quality of medical, education and infrastructure services that the company was supposed to provide in exchange for this imposed occupation of the communities’ lands.

Unfortunately, Unilever’s plantations and concessions survived the end of Belgian colonial rule over the Congo in 1960. The empty promises of “development” under the colonial occupation were followed by the same empty promises under the Mobutu’s dictatorship during the late 1960’s (when the new DRC government took a minority ownership in the company and renamed it Plantations et Huileries du Congo- PHC). They were again repeated when the Canadian company Feronia Inc bought PHC from Unilever in 2009 with over US$150 million in backing from European and US “development” banks, and then again most recently when the operations were handed over to a private equity firm based in the tax haven of Mauritius– backed this time by university endowments, philanthropic giants and pension funds. (8)

In each of these iterations, the company’s owners and investors relied on a set of manufactured land documents to justify their occupation of over 100,000 hectares of lands. When the consortium of European development banks took over PHC between 2014-2016, they were aware that PHC’s flimsy land documents had expired, and they pushed the company to manufacture a new set, fragmenting the concessions into hundreds of parcels, without consulting the local communities and without even passing through the appropriate governmental decision-making bodies. The development banks, like the owners that had come before them and that would come after, rolled out the usual justifications for this theft of community lands– schools, roads, housing health clinics and good jobs. But today the communities and workers within the PHC concessions remain desperately dispossessed and therefore poor and the company’s new private equity owners are once again promising that they will soon start adhering to the country’s labour laws, that they will soon start paying minimum wages, and that they will soon provide functioning schools and medical clinics.

The communities are sick and tired of these false promises, and want to take back their lands to produce their own palm oil and other products, as they used to do generations back. But violence keeps the company in control. PHC has outlawed artisanal oil palm mills within its concessions and villagers caught with palm nuts are routinely beaten, jailed, tortured and even murdered by PHC security guards and police, who accuse them of “stealing” nuts from the company’s disputed concessions. (9) Workers trying to improve their situation face similar violence. In early January this year, police called in by PHC opened fire on workers protesting unpaid wages at its offices in Boteka, badly injuring two villagers. (10)

The company’s response to community demands for their lands is always that if it leaves there will be no employment for the locals– as if no economy existed before Leverhulme entered the picture. PHC’s former Canadian owners, Feronia Inc, even argued that it could not give the still forested parts of its concessions back to the locals because of the risk of deforestation!

This charade of “development” should have been quashed long ago. The lands that PHC and its predecessors have stolen and occupied for over a century are, as the Belgian recognised, “rich”– and the local people know, better than any, how to care for and utilise these lands and forests for their own benefit. It is time to put an end to the colonial model of concessions and plantations, and its endless promise of “development”. The rightful interests of the communities can only be served by an immediate return of their lands. Meanwhile, those foreign agencies claiming to be concerned with “development” should shift their focus to holding Unilever and the other foreign profiteers to account for this past century of labour violations, land grabbing and other abuses and preventing companies and investors from their countries from committing more abuses.

GRAIN www.grain.org

(1) The information in this article about Leverhulme’s colonial exploitation in the Congo is derived from Jules Marchal’s incredible book, Lord Leverhulme’s Ghosts, Verso Books, 2008.

(2) Marchal, p.54

(3) Marchal, p.60 and p. 89.

(4) Marchal, p.71

(5) Marchal, p.58

(6) Marchal, p. 109

(7) Wostyn, W. 2008. De Opstand in de Districten Lac Léopold II en Sankuru (1931-1932). Een vergelijkende analyse met de Pende opstand (1931).

(8) See, RIAO-RDC, FIAN Belgium, Entraide et Fraternité, CCFD-Terre Solidaire, FIAN Germany, urgewald, Milieudefensie, The Corner House, Global Justice Now!, World Rainforest Movement, and GRAIN, “Development Finance as Agro-Colonialism: European Development Bank funding of Feronia-PHC oil palm plantations in the DR Congo,” January 2021; Oakland Institute, “Meet the Investors Behind the PHC Oil Palm Plantations in DRC,” February 2022.

(9) Numerous reports and articles detailing these abuses can be found on the website farmlandgrab.org. See here.

(10) RIAO-RDC, “Policiers et militaires tirent à balles réelles sur des ouvriers de PHC en grève à la plantation de Boteka,” January 2022.

Original Source: World Rainforest Movement

Related posts:

DR Congo oil palm company bankrolled by development banks unleashes wave of violence against villagers after peaceful protests

DR Congo oil palm company bankrolled by development banks unleashes wave of violence against villagers after peaceful protests

The enduring legacy of a little-known World Bank project to secure African plantations for European billionaires

The enduring legacy of a little-known World Bank project to secure African plantations for European billionaires

Sexual exploitation and violence against women at the root of the industrial plantation model

Sexual exploitation and violence against women at the root of the industrial plantation model

Colonization and Monoculture Plantations: Histories of Large-Scale ‘Grabbings’

Colonization and Monoculture Plantations: Histories of Large-Scale ‘Grabbings’

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

‘Food and fossil fuel production causing $5bn of environmental damage an hour’

Published

1 month agoon

December 22, 2025

UN GEO report says ending this harm key to global transformation required ‘before collapse becomes inevitable’.

Related posts:

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

New billion-dollar loans to fossil fuel companies from SEB, Nordea and Danske Bank.

New billion-dollar loans to fossil fuel companies from SEB, Nordea and Danske Bank.

Fossil fuel opponents lobby Africans for support

Fossil fuel opponents lobby Africans for support

Ecological land grab: food vs fuel vs forests

Ecological land grab: food vs fuel vs forests

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Britain, Netherlands withdraw $2.2 billion backing for Total-led Mozambique LNG

Published

2 months agoon

December 17, 2025

CONSTRUCTION HALTED IN 2021, BUT DUE TO RESTART

PROJECT CAN PROCEED WITHOUT UK, DUTCH FINANCING, TOTAL HAS SAID

CRITICISM FROM ENVIRONMENTAL, HUMAN RIGHTS GROUPS

Related posts:

Uganda, Total sign crude oil pipeline deal

Uganda, Total sign crude oil pipeline deal

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

NGOs file suit against Total over Uganda oil project

NGOs file suit against Total over Uganda oil project

Agribusiness Company with financial support from UK, US and Netherlands is dispossessing thousands.

Agribusiness Company with financial support from UK, US and Netherlands is dispossessing thousands.

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

The secretive cabal of US polluters that is rewriting the EU’s human rights and climate law

Published

2 months agoon

December 5, 2025

Leaked documents reveal how a secretive alliance of eleven large multinational enterprises has worked to tear down the EU’s flagship human rights and climate law, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). The mostly US-based coalition, which calls itself the Competitiveness Roundtable, has targeted all EU institutions, governments in Europe’s capitals, as well as the Trump administration and other non-EU governments to serve its own interests. With European lawmakers soon moving ahead to completely dilute the CSDDD at the expense of human rights and the climate, this research exposes the fragility of Europe’s democracy.

Key findings

- Leaked documents reveal how a secretive alliance of eleven companies, including Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Koch, Inc., has worked under the guise of a “Competitiveness Roundtable” to get the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) either scrapped or massively diluted.

- The companies, most of which are headquartered in the US and operate in the fossil fuel sector, aimed to “divide and conquer in the Council”, sideline “stubborn” European Commission departments, and push the European People’s Party (EPP) in the European Parliament “to side with the right-wing parties as much as possible”.

- Chevron and ExxonMobil were in charge of mobilising pressure against the CSDDD from non-EU countries. The Roundtable companies endeavoured to get the CSDDD high on the agenda of the US-EU trade negotiations and also worked on mobilising other countries against the CSDDD, in order to disguise the US influence.

- Roundtable companies paid the TEHA Group – a think tank – to write a research report and organise an event on EU competitiveness, which echoed the Roundtable’s position and cast doubt on the European Commission’s assessment of the economic impact of the CSDDD.

While Europeans were told that their governments were negotiating a landmark law to hold corporations accountable for human rights abuses and climate damage, a secretive alliance of US fossil fuel giants was working behind the scenes to destroy it. Collaborating under the innocent-sounding name ‘Competitiveness Roundtable’, eleven multinational enterprises have worked closely to eviscerate several EU sustainability laws, including the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). This Competitiveness Roundtable may be unknown, but its members are a who’s-who of polluting, mainly US, multinationals, including Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Dow. The group seems to have run rings around all branches of the EU and the Trump administration to get what they want: scrapping, or at least hugely diluting, the CSDDD.

Leaked documents obtained by SOMO reveal how, under the pretext of the now-near-magical concept of ‘competitiveness’, these companies plotted to hijack democratically adopted EU laws and strip them of all meaningful provisions, including those on climate transition plans, civil liability, and the scope of supply chains. EU officials appear not to have known who they were up against. But the documents obtained by SOMO show a high level of organisation and strategising with a clear facilitator: Teneo, a US public relations and consultancy company.

The documents indicate that many of the companies involved wanted to stay hidden from view. After all, if it were widely known that a secretive group of mostly American fossil fuel companies like Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Koch, Inc. was working as a coordinated organisation to dilute an EU climate and human rights law, that might raise questions and serious concern among the public and the policymakers they were targeting. Many of the companies in the Roundtable have never publicly spoken out against the CSDDD.

Big Oil’s ‘Competitiveness Roundtable’

The Competitiveness Roundtable is dominated by fossil fuel companies, including three Big Oil companies (ExxonMobil, Chevron, TotalEnergies) and three other companies with activities in the oil and gas sector (Koch, Inc., Honeywell, and Baker Hughes). Other members are Nyrstar (minerals and metals, a subsidiary of Trafigura Group); Dow, Inc. (chemicals); Enterprise Mobility (car rentals); and JPMorgan Chase (finance).

Teneo, the Roundtable’s coordinator, has a track record(opens in new window) of working with fossil fuel companies, including Chevron, Shell, and Trafigura, and was hired by the government of Azerbaijan to handle public relations(opens in new window) when it hosted the COP29 climate conference.

In February 2025, the European Commission published the Omnibus I proposal(opens in new window), which aims to “simplify” several EU sustainability laws, including the CSDDD. The documents obtained by SOMO reveal that the Roundtable companies, which have been meeting weekly since at least March 2025, worked on deep interventions within each of the three EU institutions to get the Omnibus I package to align exactly with their views. The EU institutions are expected to reach a final agreement on Omnibus I by the end of 2025.

The documents reveal that the Roundtable companies’ activities in the Parliament are far more significant than what is visible in the EU Transparency Register(opens in new window). Eight of the Roundtable’s lobbying meetings during the Strasbourg plenary sessions of May and June 2025, listed in the Transparency Register, show Teneo as the only attendee, thereby failing to disclose the names of other Roundtable companies that participated in these meetings. Another three meetings the Roundtable held were not found in the EU Transparency Register(opens in new window) at all.

“Divide and conquer” the Council

In the European Council, the Roundtable plotted to “divide and conquer” EU governments to get the climate article in the CSDDD deleted. In June 2025, during the final weeks of negotiations in the Council on the Omnibus I proposal, the Roundtable discussed lobbying EU government leaders to “intervene politically” to ensure its priorities were included in the Council’s negotiation mandate. Subsequently, German Chancellor Merz and French President Macron reportedly(opens in new window) personally intervened(opens in new window) in the Council’s political process, leading to a dramatic dilution(opens in new window) of the texts(opens in new window) negotiated in the months before the intervention. Several of the changes made to the texts strongly align with the Roundtable’s demands, including delaying and substantially weakening the climate obligations, scrapping EU civil liability provisions, and limiting the responsibility of companies to take responsibility for their supply chains (the ‘Tier 1’ restriction).

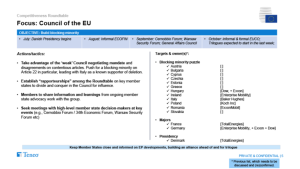

Competitiveness Roundtable meeting document, 11 July 2025.

Additionally, the documents reveal that the Roundtable is still aiming to drum up a “blocking minority” to overturn the Council’s negotiation mandate during the trilogue negotiations, which started in November 2025. By “tak[ing] advantage of the ‘weak’ Council negotiating mandate” and disagreements between EU Member States on “contentious articles”, the Competitiveness Roundtable companies hope to force the Danish Council presidency to give up on including any form of climate obligations in the CSDDD – despite EU Member States’ agreement on this in the June 2025 Council mandate(opens in new window) .

To implement the divide-and-conquer strategy, the Roundtable assigned specific companies to “establish rapporteurships” with different EU governments. TotalEnergies would target the French, Belgian, and Danish governments, and ExxonMobil would target Germany, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Romania.

Circumventing “stubborn” European Commission departments

The Roundtable also discussed working on “circumvent[ing]” two “stubborn” European Commission departments involved in the Omnibus political process, DG JUST and DG FISMA, which, in their view, were “unlikely to be willing to see our side of the story”. According to the documents, DG JUST opposed deleting the climate article and restricting the Directive’s scope to only very large enterprises. The Roundtable aimed to diminish the role of these departments by pressuring President Von der Leyen and Commissioners McGrath (DG JUST) and Albuquerque (DG FISMA) by “organising letters from Irish and German business groups” and using an event held by the European Roundtable for Industry to “target” Von der Leyen and McGrath.

Read full report: Somo.nl

Source: Somo

Related posts:

Victims of human rights violations in Uganda still waiting for redress

Victims of human rights violations in Uganda still waiting for redress

UN Human Rights Chief urges EU leaders to approve key business and human rights legislation

UN Human Rights Chief urges EU leaders to approve key business and human rights legislation

Business, UN, Govt & Civil Society urge EU to protect sustainability due diligence framework

Business, UN, Govt & Civil Society urge EU to protect sustainability due diligence framework

Development financiers fuel human rights abuses – New Report

Development financiers fuel human rights abuses – New Report

Indigenous communities in Eastern Nepal accuse the World Bank’s Linked Cable Car Project of rights violations.

Why govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

Evicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Swedish pension fund drops TotalEnergies amid rising EACOP risks

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoWomen environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoUganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

-

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoEvicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoWitness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days agoWhy govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK15 minutes ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK15 minutes agoIndigenous communities in Eastern Nepal accuse the World Bank’s Linked Cable Car Project of rights violations.