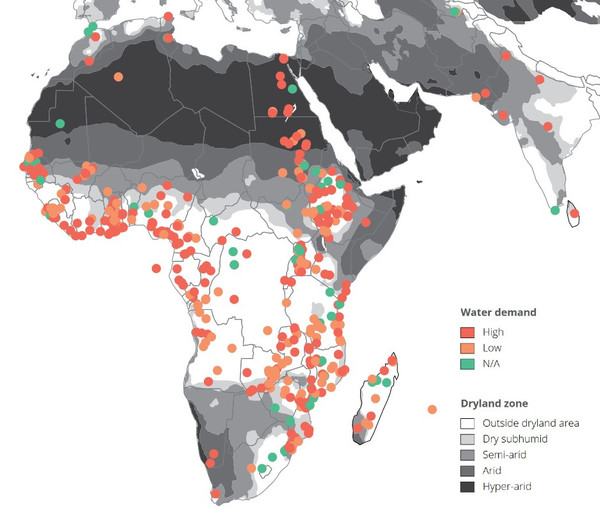

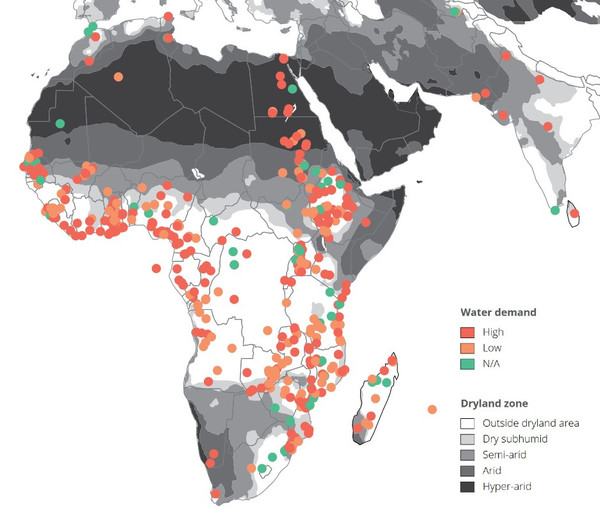

Since the early 2010s corporations have acquired over 7 million hectares of land for large-scale, industrial farms in sub-Saharan Africa, with most of these projects focused on producing water-intensive crops in already water-stressed regions. While the media spotlight is often on climate change-induced droughts, little is being said about the corporate-driven water scarcity these projects are inflicting upon people across Africa. Driven by the goal of expanding export production of water-intensive crops, governments are auctioning Africa’s water resources to the highest bidder. The new rush for land on the continent to grow trees for carbon credits is making this worse.

Water plundering

Only in the last 8 years, companies have signed land deals for over 5 million hectares for water-hungry plants in Africa. Take, for example, the New York-based company African Agriculture Holdings. It planned to use massive amounts of water from the Senegal River– the main water source for Dakar and several other major cities in Senegal, to produce alfalfa for export to South Korea and the Gulf states on 25,000 ha of land within a protected wetland. The company also planned to grow alfalfa on up to 500,000 hectares in neighbouring Mauritania, one of the most water stressed countries on the planet, and to plant a million water-hungry acacia trees in Niger to generate carbon credits. While it now appears that the company is heading for financial ruin, its CEO has already announced a new venture to grow maize on over 600,000 hectares in central Africa.

Development banks, like the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the World Bank, are working with African governments to bankroll a massive rollout of new irrigation projects across the continent to facilitate more of these agribusiness investments. In Tanzania, for instance, the government and the AfDB have budgeted hundreds of millions of dollars of public funds for large-scale irrigation projects with the private sector, with a stated goal of irrigating 8.5 million hectares by 2030– which is more than today’s total irrigated land area in all of sub-Saharan Africa.

In Kenya, President Ruto has pledged nearly US$500 million for irrigation projects nationwide, including the Rwabura irrigation project in Kiambu county, the Iriari project in Embu as well as the Kanyuambora irrigation project. The Kanyuambora, like the others, will draw water from the Thuci river and irrigate 400 hectares, which will be used to farm crops such as horticultural produce.

One company that intends to profit big from this expansion of irrigation in Tanzania, Kenya and other countries in eastern and southern Africa is South Africa-based Westfalia. The company, which is particularly active in avocado production, controls 1,200 hectares in South Africa and 1,400 in Mozambique. With support from South Africa’s government-owned Industrial Development Corporation and the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation, Westfalia is promoting the expansion of the avocado industry in countries such as Mexico, Peru, Chile and Colombia, where avocados have already fuelled a severe water crisis. Replicating this model in other African countries promises to create a similar situation.

Africa’s experience to date with large-scale irrigation projects is dismal. Most of the projects implemented over the past decades failed or are in poor condition. And many of the so-called success cases have caused more harm than good. Consider the irrigation project in Lake Naivasha, Kenya, which triggered a boom in foreign investment in flower farms in the 1980s and 1990s that serve the European and Chinese markets. Only six farms now consume over half of the water volume used for irrigation in the lake’s basin. The impact of the flower farms range from pesticide pollution, to biodiversity loss, and hampering access to safe and clean water for local people. In return there have been few benefits, with workers toiling in gruelling and hazardous conditions for meagre wages and the companies avoiding taxes.

In Morocco fruit exports-primarily destined for European and UK markets-are driven by water hungry crops such as berries, watermelon, citrus and avocados. Between 2016 and 2021 these exports more than doubled. The biggest beneficiaries of this boom are corporations as Les Domaines Export, belonging to the country’s elite, alongside foreign companies like Surexport and Hortifrut, all backed by financial players, including pension funds and development banks. Today, Morocco has more irrigated land area than any other country in Africa, aside from Egypt.

A pastoralist from Moroto one of the most dry areas in Uganda looking after his herd. Pastoralists in this region move long distances to look for pasture and water for their herds.By Nobert Petro Kalule.

A pastoralist from Moroto one of the most dry areas in Uganda looking after his herd. Pastoralists in this region move long distances to look for pasture and water for their herds.By Nobert Petro Kalule.

Export oriented industrial agriculture consumes 85% of the country’s water resources, intensifying the severe water stress gripping the kingdom, even as the country endures six consecutive years of drought. To cope with the crisis, the government announced the end of fruit subsidies. Yet, the measure will have little impact on large farms, since they have the financial capacity to continue with their operations, whereas small farmers will be the most affected. Other plans include investing in desalination plants. But the high energy and environmental costs make it far from a sustainable long-term solution.

On the opposite end of the continent, South Africa – one of Africa’s richest economy – has long struggled with a persistent water crisis. This is largely due to the fact that 65 percent of the country’s water resources are allocated to industrial agriculture.

Africa’s water custodians

The impact of industrial agriculture’s thirst for water is felt most acutely by African women. Already tasked with managing households, caring for families and farming for food, women and young girls are also responsible for collecting all the water needed for both their homes and farms.

As such, they bear the heavy burden of trekking long distances – sometimes multiple times a day – to collect water. It is estimated that African women collectively spend about 40 billion hours annually fetching water. As more of their water sources are diverted for use on export-oriented industrial farms, it will make it even harder for them to access the water they need for their households.

Paradoxically, those most affected by the water issues affecting the continent may also be the ones with the solutions. Rural women possess invaluable knowledge about local water sources, their usage, storage and conservation. They know, for example, ways of recycling water for washing, irrigation and livestock, like the women pastoralists of the Anuak people in Ethiopia’s Gambela region, know how and when to move their animals from wetter areas to drier ones in the rainy season, allowing local rivers to replenish and maintain its fertility.

In Kenya, Martha Waiganjo, a farmer from the dry lands of Gilgil, is one of many smallholder farmers working with the Seed Saver’s Network (SSN) to take advantage of rain water harvesting and conservation techniques as part of their agroecological practices. Through rain water harvesting, farmers like her are able to collect, store and conserve run off rain water for later use.

The run off water is stored in manually dug up dams that are lined with an anti-seepage layer of plastic commonly known as a dam liner. For Martha, her dam allows her to store close to 40,000 litres of water for her sustenance throughout the year. “[…] Water harvesting has been of great improvement on our farms, we don’t need the rain to plant. We use the water for irrigation and domestic use. The most important thing in water harvesting is that when the area is dry we use the water not only for farming but for the needs of the whole community. It is also of great importance to livestock farming.”[1]

In 2021, the UN estimated that nearly 160 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa (14% of the population) were affected by water scarcity and stress, and, with the effects of climate change now kicking in, the numbers are expected to be even higher in 2025 and beyond.

The fixation of governments, development banks and corporations on large-scale irrigation projects for industrial agriculture in Africa has to end. Water needs to instead be in the hands of the small-scale food producers who feed the continent and who are best able to develop solutions to the challenges posed by climate change.

Cover photo: Kenya 2011. Colin Crowley/Save the Children/ Creative Commons/Flickr

Original Source: Grain

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK6 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK6 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago