MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Why Atiak Sugar Project is not firing on all cylinders.

Published

4 years agoon

Ms Amina Hershi, the chief executive officer of Horyal Investment Ltd, displays some of the bags of sugar produced at Atyak Sugar Factory in Amuru District recently.

Atiak Sugar Limited is battling an acute shortage of sugarcane to supply the multi-billion sugar factory located in Atiak Sub-county, Amuru District. The vast bulk of its sugarcane plantations in both Amuru and Lamwo districts were ravaged by suspected arson attacks from alleged aggrieved members of two separate outgrowers societies.

The Atiak Sugar Project is still being spoken of in the present tense. It is essentially a public-private-community partnership between the National Agriculture Advisory Services (Naads), participating farmer cooperatives and respective local governments of Amuru, Lamwo and Horyal Investment Holdings Ltd.

The first bags of sugar from Horyal Investment Ltd’s multi-billion investment in the post-conflict north hit the streets of Gulu City once President Museveni commissioned the factory on October 22, 2020. The factory was initially meant to provide a ready market for the sugarcane outgrowers in the region where sugar production has already begun.

Under the partnership, the community under Atiak Outgrowers and Gem-pachilo Cooperative Societies are to plant cane on the land and weed the plantations. Once the cane is ready, the plantation—apportioned to the outgrowers by Naads—would be harvested and sold to the factory.

At its inception, the project targeted to cover 13,841 acres at the main plantation at Atiak in Amuru District. An expansion of 15,000 acres was, however, later made in Ayu-alali, Palabek Kal Sub-county, Lamwo District, in 2020. A further expansion of 31,159 acres is planned and is being established in Palabek-ogili, Lamwo District, bringing the total acreage to 60,000.

In September 2020, before its commissioning, Ms Amina Hershi, the chief executive officer of Horyal Investment Ltd, told a delegation of government officials that 3,000 acres of sugarcane were ready for supply to the factory to begin its maiden production. This section of the plantation belonged to Gem Pachilo and Atiak Outgrowers Cooperative Societies, she revealed, adding, “…we also now produce 6 MWh of electricity to the national grid, which is generated through biogas from the bi-products of the cane.”

At this point, the plant was, according to Ms Hershi, only waiting for calibration by the International Organisation for Standardisation to ensure the quality, safety, and efficiency of products, services, and systems.

Two years later, however, Saturday Monitor has learnt that simultaneous incidents of fire outbreaks that ravaged hundreds of hectares of the plantation appear to cast a dark shadow on the potential of the factory.

Outgrowers and the factory’s management accounts have indicated that since 2017, wildfires have gutted hundreds of hectares of the sugar plantation in the dry season. The burnt portions were usually canes that were nearing harvest or ready for harvest. We also understand that the portions burnt by the fire were always those owned by the outgrowers. These were not insured against fire, damages, or any other risks.

Late last month, the proprietors of the factory said sugar production had been suspended after cane supply to the factory hit rock bottom. According to the company, the suspension comes in the aftermath of wildfires that have in previous months destroyed the sugarcane plantation.

Mr Mahmood Abdi Ahmed, the company’s director for plantation and agriculture, told Saturday Monitor that production had drastically slowed down. He, however, hastened to add that operations haven’t been suspended as a result of the acute shortage of canes.

“The biggest challenge we have had is the gaps in our structural planning relating to the sugarcane production, and this failure is blamed on all of us the stakeholders,” Mr Mahmood said in an interview, adding, “The land (customary) ownership setup in the Acholi area has served a really big disadvantage to sugarcane growing because you don’t see people growing sugarcane on subsistence basis as we see in other regions producing sugar.”

According to him, in areas such as Busoga and Bunyoro sub-regions, “you find people growing sugarcane everywhere because the land is not communally owned and individuals decide on their own whether to grow sugarcane. But the communal ownership disfavours this, and this is one challenge we did not foresee.”

He also said the lack of associated amenities such as roads and urban trading centres where interested labour (workers) can reside has exacerbated things.

“The road infrastructure in communities here is still poor to boost sugarcane production,” he said, adding, “Even if communities grew these canes, the road networks are still underdeveloped to ease transportation of the canes.”

The company also lacks the infrastructure and human resources to deploy in sugarcane production. For example, Atiak Town Council or Elegu Town Council— the nearest trading centre—is 25km away from the factory, making transportation of the labour force over the distance a huge daily burden.

A fortnight ago, Ms Hersi told the media that the factory was temporarily suspending operations. According to her, the factory’s biggest problem was the lack of canes to supply the plant to produce sugar. She was, however, quick to add that the plantation would resume production once canes in Ayu-alali plantation in Palabek-kal Sub-county, Lamwo District, mature between July and August.

Sabotage galore

Ms Joyce Laker, the chairperson of Atiak Outgrowers Cooperative Society, however recently revealed that they were disappointed that Naads refused to pay their members.

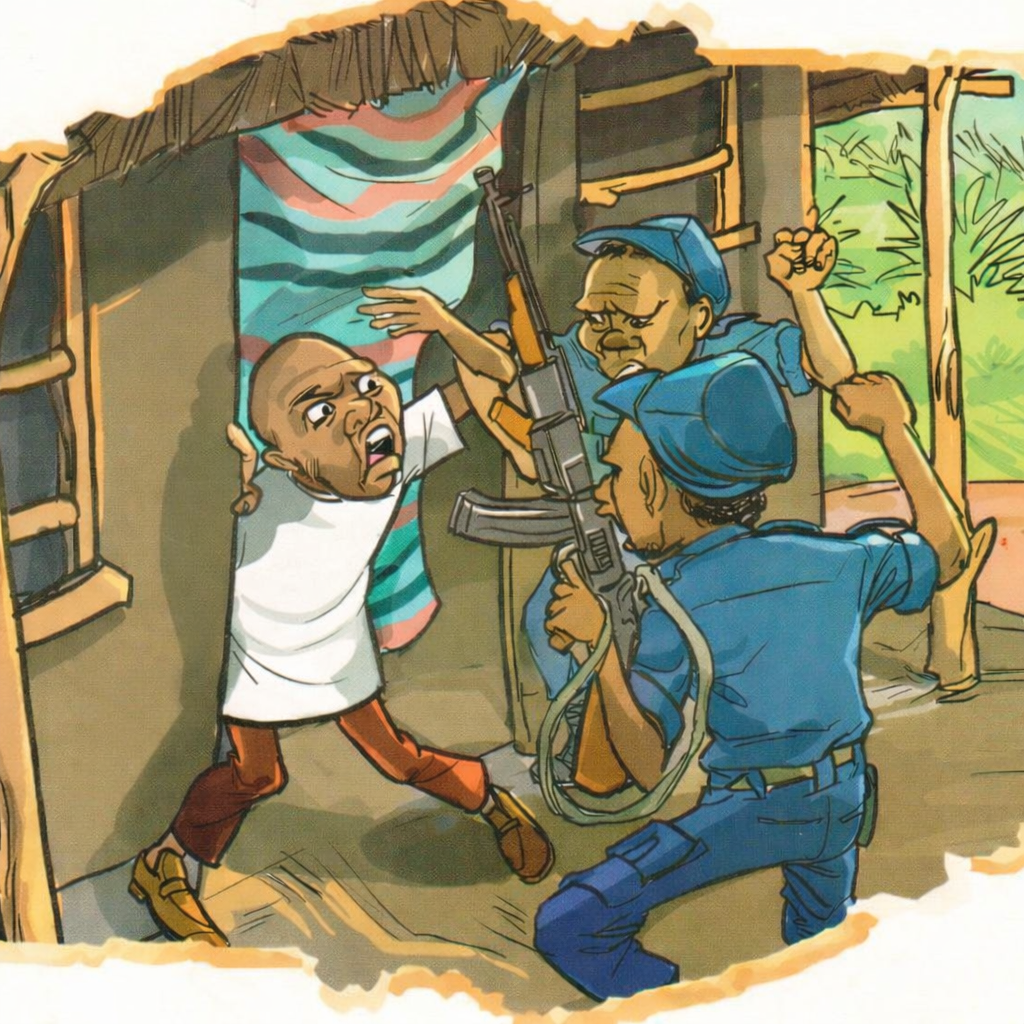

During a public gathering at the factory, Ms Laker described the wildfires that swept across the plantations as deliberate sabotage. She also called for the government’s intervention after revealing that discontented cooperative members have openly threatened to continue burning down the sugar plantation until their grievances are settled.

“I will say it without shame…,” she stated. “…there are issues which the government has to come in and settle because at one point, in a meeting, some people said if these issues are not resolved, the sugarcane will continue getting burnt down.”

The longstanding dispute between the sugarcane outgrowers and the management of the sugar factory did not only delay the commencement of sugar production. Saturday Monitor also understands that the dispute has reportedly caused persistent and deliberate burning of the canes.

Ms Laker said the finger of blame can also be pointed elsewhere.

She referred specifically to the 2017 incident when Naads cut down more than 160 acres of sugarcane plantations belonging to Atiak Outgrowers and Gem-pachilo cooperative societies.

Saturday Monitor has established that the outgrowers are yet to be paid. We have also established that there are several instances of tension between the outgrowers, Horyal Investment Ltd and Naads over royalties and accumulated payments for canes cut and served to the factory.

Before President Museveni launched the factory in October 2020, the farm could not initialise sugar production for nearly eight months. This was due to the failure of the government to compensate two cooperatives for the sugarcane supplied to the factory.

Ms Grace Kwiyocwiny, the State Minister for Northern Uganda, told Saturday Monitor that roundtable talks between the leadership of the factory and the cooperative members are in the offing.

“We should protect all the little developments that are coming up in our region because all developments are supported by communities,” she said, adding, “I want to … come and meet with the leaders of the community because of the sugar [cane] that is continuously burning down.”

Earlier in March, when this newspaper visited the facility, the factory remained closed to production due to supply chain issues (shortage of cane). A perfect storm—including the pandemic, suspected arson attacks and insufficient production of canes by plantations in both Amuru and Lamwo districts—has contrived to create supply chain problems.

No respite from the east

In January 2021, Horyal Investment Ltd started sourcing its cane from the Busoga Sub-region. Sugarcane farmers in Busoga Sub-region, under the Greater Busoga Sugarcane Farmers’ Union (GBSGU), last month signed a memorandum of understanding with Atiak Sugar Factory to supply cane for six months. Under the arrangement, the government shall intervene by subsidising the transport costs and also avail fueled trucks to ferry the cane.

Inside sources have, however, told Saturday Monitor that the arrangement looks to have fallen flat on its face. The cost the investor incurred in transporting a truckload of canes is six times higher than what it paid for canes alone. A source who did not want to be named said while a truckload of canes fetched approximately Shs200,000, it costs between Shs800,000 to Shs1m to transport the consignment.

“They failed to sustain that arrangement because it was very expensive and the company realised it was sinking in losses to that effect; although the costs were being shared between the investor and Naads,” our source revealed.

Mr Michael Lakony, the Amuru District chairperson, fears that the suspension of the sugar production will destroy livelihoods in the sub-region.

“Hundreds of workers, including young men and women from the district here have been rendered jobless,” he told us in an interview, adding, “If the company wants to gain from the factory, it should get serious other than politicking.”

Mr Lakony added that because the government was allegedly not serious about streamlining the impasse and ensuring that Horyal Investments Ltd respects its terms in dealing with the outgrowers, the investor could continue grappling with suspicious fires.

“The plantations keep getting burnt because it is owned by no one and that means nobody cares, and if nobody cares, no one takes interest in taking care of it, including the neighbours because benefits in terms of payments to the out-growers are not being met,” he said.

Mechanisation drive

To address the challenge of labour deficiency and lack of funds to establish low-cost housing facilities in the factory to accommodate workers, Mr Mahmood said they are moving towards mechanising production.

“We don’t have the financing to build accommodation facilities to house thousands of workers who we would need to work on the plantation daily,” he told Saturday Monitor, adding, “Instead, we are strategising to focus on mechanising our production using the limited resources at our disposal now.”

He further revealed that they have procured a new fleet of sugarcane planters, weeders and harvesters due to arrive at the back-end of this year.

“The machines, we believe, are more efficient and can do much more work compared to human labour and that will solve the puzzle,” he noted.

Although Mr Mahmood did not disclose the source of the funding, in a separate interview, Mr Lakony—the Amuru LC5 chairperson—said the company had been granted a Shs108 billion bailout by the government for mechanising production.

“We had a meeting with the management as a district and also shareholders and the latest update is that the government has allocated Shs108 billion to the company through UDC [Uganda Development Corporation],” Mr Lakony said, adding, “The plan is to leave rudimental and turn to mechanised production. Instead of using human labour, they want to use machines.”

A fraction of the same funds will also be used to establish an irrigation system on River Unyama that cuts through the sugar plantation to help in irrigating the canes during the dry season when immature and young canes dry and die out, Mr Lakony added.

Saturday Monitor understands the Shs108 billion is the same funding thrown out by Parliament’s Budget Committee last November. This was after the investor made a supplementary budget request to finance production. The request tabled by junior Trade minister David Bahati, and backed by the UDC’s top brass, failed to convince the lawmakers, who in turn sent them away.

The MPs declined to endorse Ms Hersi’s request to the government, reasoning that there was a need for proof that her investment was making a substantial contribution to the economy. The MPs instead demanded a forensic audit into how she has spent more than Shs120 billion received from the government. Similar financial requests were made by the Atiak Sugar leadership to the 10th Parliament, but most of them were rejected, although it later emerged that they were, nevertheless, granted.

Some of the fire incidents at Atiak Sugar project

In 2016, a fire caused an estimated loss of Shs150m after it gutted 150 acres of sugarcane plantation at the factory.

In December 2018, another mysterious fire destroyed an estimated 250 acres of sugarcane at the facility.

An estimated 600 acres of sugarcane at the plantation was then burnt down in February 2019.

And in January 2021, a fire that lasted for nearly a week destroyed nearly 60 percent of the plantation after the police fire brigade fought it with little success.

Eventually, more than 600 acres of sugarcane estimated at Shs3 billion were reported to have been destroyed in the fire.

In fact, that fire in January of 2021 was the worst to ever hit the plantation. The police attributed the rapid spread of the fire to narrow fire lines that do not allow fire trucks to move in fast.

Enter January of 2022, a similar fire burnt down an estimated 3,500 acres of the sugarcane plantation.

According to Mr David Ongom Mudong, the Aswa River Region police spokesperson, the fire razed down 14 huts belonging to a Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF) detachment. The soldiers, who were supposed to stand as sentinels at the plantation, watched helplessly as 250 acres were burnt down.

Background

About the factory

Atiak Sugar Factory, located at Gem Village in Pachilo Parish in Atiak Sub-county in Amuru District, is jointly owned by the Uganda and Horyal Investment Holdings Company Ltd. The latter belongs to Ms Hersi.

The factory—located 17kms north of Atiak off the Gulu-Nimule Road—is the first major investment in the region.

Lawmakers have, however, continued to question why the government’s stakes in it have remained significantly low compared to that of Horyal Investments despite the huge capital portfolio injected in the past years into the venture.

Last September, Parliament’s Committee on Trade questioned why the government—the lowest shareholder in Atiak Sugar Limited—continues to invest the most money in the factory.

The government’s shareholding in the plant has remained static at 40 percent despite an injection of more than Shs120 billion.

In May 2018, when the government injected Shs20 billion, its shareholding stood at 10 percent. In the same year, it injected another Shs45 billion—raising its shares to 32 percent.

The committee also questioned the circumstances under which Naads contracted the company to clear, plant, and harvest sugar cane valued at Shs54 billion instead of working directly with the outgrowers.

Source: Daily Monitor

You may like

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Indigenous communities’ complaint against World Bank-linked Nepal Cable Car Project declared eligible for investigation.

Published

7 hours agoon

February 5, 2026

By Witness Radio team

Indigenous Yakthung (Limbu) communities in eastern Nepal have fought hard for recognition after the World Bank Group’s accountability mechanism acknowledged a complaint about rights violations, underscoring their ongoing struggle to protect their land and culture.

The Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO), the independent watchdog of the World Bank Group, accepted the complaint for further assessment and formally registered the case in December 2025. The decision clears the way for a potential mediation process or a full compliance investigation into whether the project breached the IFC’s environmental and social safeguard standards.

In August 2025, Indigenous Yakthung leaders, supported by lawyers and civil society organizations, filed a complaint against the IFC’s advisory support to IME Group for the $22 million Pathivara (Mukkumlung) cable car project in Taplejung District. This filing marks a critical step in holding the project accountable for alleged rights violations and environmental harm.

The cable car is being constructed on Mukkumlung Mountain, a sacred ancestral landscape central to the Yakthung people’s spirituality and Identity, risking irreversible damage to their cultural heritage and Identity.

According to the complainants, construction has already resulted in the felling of more than 10,000 trees in and around the Kanchenjunga Conservation Area, threatening habitats of endangered species such as red pandas, snow leopards, and Himalayan musk deer, underscoring the project’s severe environmental consequences.

“The reason the Complainants and their advisors seek to engage with the CAO is because of the social and environmental harms caused by one of the cable car projects in particular, the Pathivara project. This cable car project has severe impacts on one of the most sacred sites of the Limbu (Yakthung) Indigenous Peoples, including their forests, flora, fauna, heritage (tangible and intangible), and Mukkumlung mountain. The Pathivara project has been imposed on the local Indigenous communities without their Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), and has proceeded to destroy their lands, forests, sacred sites, and livelihoods. When the people protest, they have been met with extreme violence and repression by security forces.” The community complaint submitted to the Ombudsman in August 2025 read.

Between August 2022 and July 2024, the IFC provided advisory services to IME Group related to four cable car projects in Nepal, including the Pathivara project. The complainants allege that the IFC failed to ensure that its Environmental and Social Performance Standards, particularly those protecting Indigenous Peoples, were applied.

“The cable car project is tantamount to cultural genocide of the Limbu nation in violation of our rights guaranteed in Nepal’s constitution, the Treaty of 1774 with the Gorkha kingdom, and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,” said Advocate Shankar Limbu, Vice-Chair of LAHURNIP.

Community members say they were unaware of IFC’s involvement until July 2024, nearly two years after construction began, due to the delayed public disclosure of the advisory support.

Accordingly, the complaints stated that the project did not meet the IFC Performance Standards, including failures to assess and manage project impacts, conduct land acquisition, and address involuntary resettlement, among others.

“The IFC’s inability to ensure its client integrated the Performance Standards into the implementation of its plan for delivering cable car projects around Nepal has led to severe breaches of the protections that were supposed to safeguard vulnerable and marginalized communities. Today, Indigenous Limbu communities are being beaten, shot at, arrested, and terrorized for trying to defend their land and way of life,” the community complaints read.

Although the IFC exited the advisory role in 2024, it continues to invest in Global IME Bank, Nepal’s largest commercial bank and a core company within the IME Group. Over the past decade, the IFC has provided more than $50 million in financing to the conglomerate, along with a $500 million trade finance guarantee, which critics say gives the institution ongoing leverage and responsibility.

In its eligibility determination, the CAO found that the complaint met the required criteria, including a plausible link between IFC-supported activities and the alleged environmental and human rights harms. The case has now entered a 90-day assessment phase, during which the CAO will consult with the affected communities, the IFC, and the company involved.

At the end of the assessment, the parties may choose to engage in dispute resolution through mediation or proceed to a full compliance investigation examining whether the IFC failed to follow its own safeguard policies.

The advocates representing the communities welcomed the CAO’s decision.

“We welcome the fact that the CAO has found this complaint eligible, and look forward to working with investigators to uncover how things went so badly wrong. The IFC is currently reviewing its Performance Standards and must learn lessons on consultation, safeguarding cultural heritage and biodiversity, respecting Indigenous Peoples’ rights, and protecting them against retaliation,” Kate Geary, Programme Director at Recourse, one of the organizations that supported the communities in the complaint, reveals.

Further, their appeal is for the CAO to handle the case with utmost urgency. “The CAO investigation into the complaint against the cable car project should move swiftly to remedy ongoing impacts of the project, including retaliations against the local communities,” added Advocate Shankar Limbu.

Indigenous leaders are demanding an immediate halt to construction, the withdrawal of security forces from the area, the release of all IFC-related project documents, and an independent investigation into alleged human rights abuses, urging urgent action to protect their rights and environment.

Related posts:

CSOs call for meaningful changes in the World Bank’s Dispute Resolution Service to foster access to justice for project-affected communities.

CSOs call for meaningful changes in the World Bank’s Dispute Resolution Service to foster access to justice for project-affected communities.

The World Bank Must Be Held Accountable for Harm Inflicted on Tanzanian Communities by Tourism Project

The World Bank Must Be Held Accountable for Harm Inflicted on Tanzanian Communities by Tourism Project

Witness Radio – Uganda and partners welcome a public acknowledgment of the complaint lodged before the World Bank’s Inspection Panel.

Witness Radio – Uganda and partners welcome a public acknowledgment of the complaint lodged before the World Bank’s Inspection Panel.

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

The Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network Joint Radio program boosts Farmers’ knowledge of seed and food sovereignty.

Published

2 days agoon

February 4, 2026

By Witness Radio team

Across Africa, seed laws are increasingly structured to favor commercial seed systems, leaving smallholder farmers with limited control over the seeds they rely on for food production. While governments often justify these laws as necessary for quality control and increased productivity, farmers and civil society organizations argue that they deepen dependency, erode Indigenous knowledge, and undermine food sovereignty.

Smallholder farmers produce the majority of the world’s food. Recognizing practices such as saving, exchanging, and replanting seeds can empower farmers and reinforce their vital role in food security.

In response to this challenge, Witness Radio, in partnership with the Seed Savers Network (SSN) in Kenya, is joining hands to save African indigenous seeds by using media to build power and share knowledge and skills with smallholder farmers across Africa and beyond on seed sovereignty and farmer-led food systems.

Last Thursday, Witness Radio and the Seed Savers Network aired the first episode of the program live, featuring representatives of smallholder farmers and civil society organizations from across the African continent. The discussion, which was live on Witness Radio, focused on sharing Indigenous knowledge and practical approaches to saving and conserving African Indigenous seeds.

“It is a crucial time to speak about food sovereignty because, as Indigenous People, talking about food sovereignty is not just an agricultural issue, according to us. It’s a vital act of decolonization and a sign of cultural survival to us and also self-determination.” Said June Bartuin, the Executive Director for Indigenous Peoples’ for peace and climate justice, Kenya, during the first episode of the program.

Across Africa, several policies and laws restrict farmers’ rights to save, exchange, and sell their own seeds. In East Africa, the recently introduced EAC Seed and Plant Varieties Draft Bill 2025 has sparked protests from smallholder farmers and activists, who argue that some of its provisions threaten farmer-led seed systems and favor multinational seed companies.

In Ghana, the Plant Variety Protection Act of 2020 restricts farmers’ seed management practices, underscoring the urgent need for policy reforms that support farmer-led seed systems.

“We have this Plant Variety Protection Act of 2020, which has made it easier for seed companies and the commercial sector to control the seed system,” said Atim Robert Anaab, who works with Trax Ghana and the Beela Project in Northern Ghana, adding that, “The law requires seeds to be certified according to standards that most small-scale farmers simply cannot meet.”

Such laws have reshaped Africa’s food systems by pushing farmers toward commercial seeds that must be purchased every planting season. These seeds are often sold alongside chemical fertilizers and pesticides, significantly increasing production costs for smallholder farmers.

Priscilla Nakato, Chairperson of the Informal Alliance of Communities Affected by Irresponsible Land-Based Investments in Uganda, noted that these policies have also displaced traditional storage and seed preservation practices.

“In the past, every household had a granary, used not only to store food but also to preserve seeds for the next planting season. Many communities still hold this resilience, and reviving these practices can inspire hope for food sovereignty.”

Beyond economics, restrictive seed laws are accelerating the erosion of Indigenous knowledge and cultural practices. June Bartuin explained that women were traditionally the custodians of seeds, preserving them using low-cost methods such as smoke storage in traditional houses.

“This maize could be stored for two, three, even five years, and when planted, it germinated very well,” she added.

The collaboration between Witness Radio and the Seed Savers Network brings together grassroots organizing and community media to amplify farmers’ voices. The Seed Savers Network, a grassroots organization based in Kenya, works with more than 500,000 farmers and supports 121 community seed banks across the country.

According to Mercy Ambani, Resource Mobilization Officer at Seed Savers Network, the organization focuses on rebuilding farmers’ confidence, knowledge, and rights, making platforms such as Witness Radio ideal for reaching farmers directly.

“Our vision is to protect seed sovereignty, conserve biodiversity, and strengthen farmers’ rights through policy advocacy and practical action,” she said.

Through initiatives such as the Seed School, farmers, researchers, and activists are trained in seed selection, storage, preservation, and community seed bank management.

“In December 2024, Kenyan farmers achieved a landmark court ruling that struck down parts of the Seed and Plant Varieties Act, showing the power of collective action and legal advocacy to protect farmers’ rights.”

“This ruling showed that there is power in numbers,” said Ambani. “When farmers raise their voices together, change is possible.”

Regional knowledge exchange is also growing. Farmers from Uganda and Ghana who attended the Seed Savers Boot Camp have returned to their communities to establish household seed banks, kitchen gardens, and farmer field schools.

“My home has become a farmer’s field school. People are hungry for this knowledge,” said Nakato.

Without reforms that recognize and protect farmer-managed seed systems, farmers risk losing control over their seeds — and with them, control over food, culture, and livelihoods.

“If we lose our seeds, we lose our culture, our food, and our future,” Bartuin emphasized.

Wokulira Geoffrey Ssebaggala, Team Leader at Witness Radio, highlighted the importance of creating space for farmers to share knowledge and experiences.

“We are providing a platform where farmers and experts can exchange knowledge on sustainable farming practices. We believe this radio content will have a real impact on food and seed sovereignty across Africa.” Mr. Ssebaggala added.

The radio series will continue to provide practical knowledge, farmer voices, and policy analysis to support sustainable agriculture across Africa.

Related posts:

Happening shortly! Kenya’s upcoming court ruling on the Seed Law could have a significant impact on farmers’ rights, food sovereignty, and the country’s food system.

Happening shortly! Kenya’s upcoming court ruling on the Seed Law could have a significant impact on farmers’ rights, food sovereignty, and the country’s food system.

Seed Sovereignty: Most existing and emerging laws and policies on seeds are endangering seed saving and conservation on the African continent.

Seed Sovereignty: Most existing and emerging laws and policies on seeds are endangering seed saving and conservation on the African continent.

The EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025, is a potential threat to smallholder farmers, as it aims to disengage them from the agriculture business, according to experts.

The EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025, is a potential threat to smallholder farmers, as it aims to disengage them from the agriculture business, according to experts.

Seed Boot Camp: A struggle to conserve local and indigenous seeds from extinction.

Seed Boot Camp: A struggle to conserve local and indigenous seeds from extinction.

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Close to six years on, Pangero Chiefdom subjects still linger in pain after the government army’s forceful takeover of their ancestral land.

Published

2 days agoon

February 3, 2026

By Witness Radio Team

It was a bolt from the blue—an unimaginable shock that arrived without warning. Close to six years on, its consequences have hardened into everyday reality, and justice remains elusive. That shock was felt most acutely in Pangero Chiefdom, where a once-stable community is still grappling with the aftermath of an abrupt and forceful military land takeover, highlighting ongoing land injustice.

The Pangero Chiefdom of the Alur Kingdom is located in Koch Parish, Nebbi Sub-County, Nebbi District, in north-western Uganda, north of Lake Albert and near the Uganda–DR Congo border. For decades, families here depended on the land for farming, food, and cultural continuity, with traditions and livelihoods deeply tied to the soil.

The wounds from the land loss remain raw, and the community continues to demand the return of their land and justice for their suffering.

Over 100 families across Aleikra, Kochi Central, and Panyabongo villages have been directly impacted by the land grab, according to the Traditional Chief.

In Uganda, land is often taken from people with low incomes through a system lacking explicit legal protections, raising questions about the legitimacy and fairness of land seizures, especially when communities are evicted without free, prior, and informed consent.

“When forces such as the Army occupy community land, people are always afraid even to ask why they are settling or why they have settled on their land. It becomes difficult to question men in uniform,” said Mr. Ulama Dison Duke Ukerson, the Traditional Chief of Pangero Chiefdom, in an interview with Witness Radio Uganda.

In March 2020, hell broke loose in the chiefdom as residents woke up to find UPDF soldiers camping on their land. Many initially thought the soldiers were temporarily stopping over on their way elsewhere. However, after some time, it became clear that the force was not moving on but instead settling in the lush environment of Pangero.

When confronted, residents claim the soldiers explained that they were taking refuge, with Zombo District as their ultimate destination.

“They have stayed there for now, close to six years. Initially, they told us they would take refuge for a few days and later move to the Zombo District. Some left, but others remained. We initially thought they were staying for a few weeks. Since then, they have stayed on our land without paying anything,” said Gladys Budongo, an elder in the chiefdom, in an interview with Witness Radio.

Forty-one-year-old Doreen Kawambe, a resident of Aleikra Village, is among those who lost part of their land during the takeover. Doreen said she originally owned seven acres inherited from her father.

“When the UPDF came, they seized three acres of our land. The remaining land is difficult to access. My family was left with only four acres. We can no longer go to the forest for water, and the areas we used to cultivate are now guarded. Food has become a serious problem,” she said.

Before the takeover, Doreen’s land provided enough income to sustain her family. “From one acre, I could earn up to 800,000 shillings (about 224.94 USD) or more in a season. Now, with less land and limited access, survival is tough.” She explained.

Gladys Budongo, a 61-year-old widow, also lost her late husband’s five-acre family land, which is part of a larger ancestral estate that the family has occupied for decades.

Amid community resistance and ongoing efforts to reclaim their land, the Army conducted surveys and valuations in 2023 and 2024. However, elders like Gladys Budongo claim the process was irregular and imposed without community consent, highlighting the need for legal accountability.

“Koch Land Committee also pressured the community to accept the survey exercise. Although it was supposed to represent the local population, it was not democratically elected by consensus, as is traditional in Alur communities, and instead consisted of an imposed elite who pressured us to surrender our land,” she said.

According to elders interviewed by Witness Radio, during an announcement meeting on September 19, 2025, facilitated by officials from the UPDF Land Board, the national surveyor, and the Commander of Koch Army Barracks, community members were compelled to sign documents accepting meager compensation for land seized five years earlier.

“Residents whose land was surveyed were given two choices: either sell their land to the Army by accepting the compensation offered or refuse the UPDF’s offer,” the area chief said, adding that officials barred him from speaking or defending his chiefdom.

“Leaders in the area are rough when we oppose this land grab. Even in meetings, they don’t allow me to speak. On the few occasions I attended and got silenced,” he said.

Mr. Opio Okech, a community land defender, blamed the government and the Army for forcefully occupying people’s land.

“The forced decision to sell land to the government is similar to eviction because people have no say. The problem started when the government entered the land, stayed for a long time without proper notice, and then decided it would not leave and instead offered compensation. It looks, smells, and walks like a forceful eviction,” he said.

Despite promises of compensation, Gladys and others say they have not received any payment.

“They forced people to sign documents, but nobody has been paid yet. Some were threatened with arrest if they protested,” she said.

Koch Resident District Commissioner (RDC) Mr. Abak Robert, representing the Office of the President, denies allegations of land grabbing, stating the land was acquired on a willing buyer, willing seller basis, which raises questions about the transparency and legality of the process.

“I personally participated in monitoring the project-affected persons. People who accepted giving land to the UPDF were properly valued, accepted the figures, and signed willingly,” he said in an interview with Witness Radio.

When asked how this arrangement worked, given that compensation was considered only after the land had already been forcibly taken, he responded that the government would soon pay the affected people.

“Compensation is expected soon, and the community is agreeable to receiving monetary payment,” the RDC added, noting that the land currently occupied by the UPDF in Pangero Chiefdom spans more than 242.811 hectares.” He added.

However, affected residents insist that the survey and valuation process involved intimidation and coercion.

Capt. David Kamya, the 4th Division Public Information Officer based in Gulu District, declined to comment about the UPDF’s improper land acquisition upon being contacted by Witness Radio.

“How sure are you that the UPDF grabbed the land? I was told that if someone wants to talk about such matters, they must be on the ground. Come, and we meet and see this physically,” he said before hanging up.

The consequences of the land seizure extend beyond economics. According to the chiefdom elders, families struggle to sustain livelihoods, children go hungry, and elders feel powerless in the face of military authority.

“People are afraid to speak out. We are threatened when we ask for justice. It feels like the community has no voice. The loss of ancestral land is also cultural. Trees, rivers, and open spaces that connected generations have been taken over, disrupting a way of life that has lasted centuries,” she added.

Nearly six years after the UPDF’s arrival, the Pangero Kingdom remains a community in limbo.

“We want someone to stand for us to stop them from taking our land or even buying it as they promise. They refuse to hear the elders’ voices and do whatever they want. We want our land back,” said the traditional chief, whose houses now accommodate soldiers.

Related posts:

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Uganda’s plan to allow forceful takeover of private land stirs anger

Uganda’s plan to allow forceful takeover of private land stirs anger

Ugandan army to punish soldiers for torturing Journalist in Kampala

Ugandan army to punish soldiers for torturing Journalist in Kampala

Nine (9) years and still counting: Buvuma residents still await compensation for land grabbed by the Oil palm project.

Nine (9) years and still counting: Buvuma residents still await compensation for land grabbed by the Oil palm project.

Indigenous communities’ complaint against World Bank-linked Nepal Cable Car Project declared eligible for investigation.

The Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network Joint Radio program boosts Farmers’ knowledge of seed and food sovereignty.

Close to six years on, Pangero Chiefdom subjects still linger in pain after the government army’s forceful takeover of their ancestral land.

Indigenous communities in Eastern Nepal accuse the World Bank’s Linked Cable Car Project of rights violations.

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Swedish pension fund drops TotalEnergies amid rising EACOP risks

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoWomen environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

-

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoEvicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoWitness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days agoIndigenous communities in Eastern Nepal accuse the World Bank’s Linked Cable Car Project of rights violations.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK6 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK6 days agoWhy govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days agoClose to six years on, Pangero Chiefdom subjects still linger in pain after the government army’s forceful takeover of their ancestral land.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days agoThe Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network Joint Radio program boosts Farmers’ knowledge of seed and food sovereignty.