NGO WORK

WTO negotiations: In the face of the food crisis, public stocks are legitimate and necessary

Published

3 years agoon

WTO negotiations:

In the face of the food crisis, public stocks are legitimate and necessary

The EU must stop attacking the food sovereignty of the countries of the Global South

From 12 to 15 June, the WTO ministerial meeting will be held in Geneva. In the context of multiple simultaneous crises (covid-19, climate crisis, war in Ukraine, debt…) that lead to numerous food crises, ECVC considers that the negotiation position of the European Union is unacceptable.

A large number of Southern countries defend their right to maintain public policies of public food stockholdings, market regulation and support to their local agriculture[1]. States have a responsibility to ensure the stability of food supply for their population. These policies are legitimate and necessary, they are the basis for food sovereignty.

However, the European Union, together with the United States and other agro-exporting countries, is constantly using the WTO to attack the food sovereignty of the South. The EU claims that these public policies create trade distortions. But should the countries of the South let their populations starve to death in order to comply with free trade rules set up by and for the interests of multinational companies from rich countries?

At a time when the price of cereals on international markets is reaching record highs, it is clear that the strategy of making countries’ food security dependent on international trade is a failure. However, the EU continues to press through the WTO to increase market access for third countries and to denounce their public support for agriculture. It is even threatening countries in serious difficulty, such as India and Egypt, with litigation before the Dispute Settlement Body if they do not abandon their policies in favour of public food stockholdings. For Morgan Ody, a peasant farmer member of ECVC’s Coordination Committee, “these positions are outrageous and in no way represent the demands of European farmers or of society as a whole”.

According to ECVC, instead of criticizing the countries of the South, the European Union should take inspiration from them to deeply reform the Common Agricultural Policy, encourage public stockholdings in all member countries and regulate the agricultural markets in order to ensure stable and fair prices for both producers and consumers. In Europe too, in the face of the difficulties linked to the climatic and geopolitical crises, we need strong public policies supporting relocalised and agroecological production, based on a large number of peasant farmers.

WTO out of agriculture!

Food Sovereignty Now!

[1] As discussed at a seminar on food security organised by the WTO on 26 April.

The press release is also available in pdf here

Original Source: European Coordination Via Campesina

Related posts:

How the EU-Mercosur trade deal is worsening the international climate crisis

How the EU-Mercosur trade deal is worsening the international climate crisis

UN Food Systems Summit: The Battle Over Global Food and Agriculture Governance

UN Food Systems Summit: The Battle Over Global Food and Agriculture Governance

UN warns over looming food crisis in Uganda

UN warns over looming food crisis in Uganda

New IFAD fund launched to help prevent rural food crisis in wake of COVID-19

New IFAD fund launched to help prevent rural food crisis in wake of COVID-19

You may like

NGO WORK

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

Published

2 weeks agoon

July 2, 2025

Villagers living in the shadow of Ruaha National Park (RUNAPA) are under siege from a rogue –World Bank-funded paramilitary ranger force. Accountability Now – Tanzanian Communities Shattered by World Bank-funded Tourism Project, a new Oakland Institute report, shines a spotlight on the human toll of the Bank’s ongoing failure to correct the dire crisis it has created.

As previously exposed by the Institute, the Resilient Natural Resource Management for Tourism and Growth (REGROW) project enabled the violent expansion of RUNAPA in Tanzania, resulting in grave human rights abuses, devastation of livelihoods, and planned widespread evictions. These damning findings were confirmed by the Bank’s own Inspection Panel in its September 2024 investigation report. Accountability Now details the severely delayed and deficient action taken by the Bank in response to the blatant violation of its safeguards, which has allowed the cycle of violence and suffering to persist.

“This report is not only a scathing indictment of the Bank’s irresponsible financing and mishandling of the case, but also of the institution’s absence of accountability given its failure to correct its wrongs at every step. The Bank’s management admitted its responsibility for enabling this crisis – and yet, it has turned its back on villagers as human rights abuses and crippling livelihood restrictions continue unabated,” said Anuradha Mittal, Executive Director of the Oakland Institute.

The report documents how the Bank’s funding allowed the government to double the size of RUNAPA by over one million hectares through Government Notice 754 in October 2023 without the consent of those living on this land. This placed over 84,000 people from at least 28 villages at the risk of imminent eviction and resulted in over US$70 million of economic losses for farmers and pastoralists – suffering compounded by killings and violence at the hands of rangers funded by the Bank.

Between 2017-2024, the Tanzania National Parks Authority (TANAPA) rangers were equipped and emboldened by the World Bank, enabling the agency to carry out a brutal campaign against local residents. Communities have endured extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, torture, and sustained economic hardship – made possible by the Bank’s lack of oversight.

The World Bank-financed REGROW project was officially cancelled on November 6, 2024. On April 1, 2025, the Bank’s Board of Directors approved an Action Plan (MAP) to address the findings of the Inspection Panel’s investigation into the project. Instead of remedying the harms identified by the Panel and responding to the demands of the impacted communities, the MAP chose to narrowly focus on alternative livelihoods and accepted the government’s dubious promise that villages consumed by the park would not be resettled and residents could continue grazing, fishing, and farming.

Barely a month later, on April 26, 2025, 27-year-old fisherman Hamprey Mhaki disappeared after being shot by rangers in the Ihefu Basin. On May 7, rangers opened fire on herders in Iyala village, killing 20-year-old Kulwa Igembe, and seizing over 1,000 cattle in another devastating economic blow to herders.

The World Bank made a commitment to work with the Tanzanian government to “support communities in and around RUNAPA in an effort to balance conservation and development, including reducing incidences of conflict and violence in the Park and providing alternative livelihoods.” The latest killings, cattle seizures, and farming restrictions, expose the hollowness of the Bank’s commitment. Several villages have been instructed to relocate – directly contradicting the government’s prior assurances. Though it claims to be supervising the implementation of the MAP, the Bank’s management has entrusted the very government responsible for the violence to investigate it.

“If the core promise to allow daily life to resume for the villagers is not honored, their very survival is at risk. Impacted communities expected the Bank to supervise the MAP. They are appalled by the Bank’s response that the perpetrators of violence will provide them with justice. Given the Tanzanian government’s horrific record of human rights abuses, this is akin to letting the fox guard the henhouse,” Mittal concluded.

The time to deliver redress is long overdue. One impacted villager said, “We are crying for our lands…let us be free. We don’t want to leave and the World Bank should stop the government from taking our lands. Our suffering is directly because of the Bank. Let us be free.”

Source: oaklandinstitute.org

Related posts:

The World Bank Must Be Held Accountable for Harm Inflicted on Tanzanian Communities by Tourism Project

The World Bank Must Be Held Accountable for Harm Inflicted on Tanzanian Communities by Tourism Project

World Bank Project Cancelled in a Landmark Victory for Tanzanian Villagers

World Bank Project Cancelled in a Landmark Victory for Tanzanian Villagers

NGO WORK

World Bank-Funded TANAPA Rangers Murder Two Villagers in Ruaha National Park

Published

2 months agoon

May 22, 2025In the last two weeks, TANAPA rangers have killed two villagers within the disputed boundaries of the Ruaha National Park in Tanzania. These murders shatter promises made just a month ago by the Tanzanian government and the World Bank to end ranger violence and allow livelihood activities to continue within the park.

On April 26, 2025, six fishermen were confronted by rangers outside of Mwanjurwa, near Ikanutwa and Nyeregete villages in the Ihefu Basin. As they tried to escape, rangers shot 27-year-old Hamprey Mhaki in the back. It is believed that Mr. Mhaki succumbed to his gunshot wound, as the search party only found a large amount of blood where he was last seen. He remains missing – while his pregnant wife and grieving family search for answers and demand justice.

In another incident, on May 7, 2025, a group of herders and their cattle in the Udunguzi sub-village of Iyala village were attacked by a TANAPA helicopter that opened fire with live ammunition. Eyewitnesses report that Kulwa Igembe, a 20-year-old Sukuma herder, was shot in the chest by one of the rangers on the ground. He died at the scene. Mr. Igembe is survived by his widow and young daughter.

According to Tanzanian media, four TANAPA rangers are being held by the Mbeya Regional Police Force for their involvement in Mr. Igembe’s killing. His body remains at the Mochwari Mission hospital, as his family has refused to proceed with burial until authorities conduct a full and transparent investigation. Furthermore, local sources state that over 1,000 cattle belonging to several herders were seized and impounded at the Madundasi ranger post following the attack. About 500 cattle have been reclaimed after herders paid TSh100,000 per head [US$37] in fines – delivering a substantial financial blow.

The Bank’s REGROW project, now cancelled, built the enforcement capacity of the rangers who committed these murders. In the 2024 investigation by its Inspection Panel, the Bank conceded that by “enhancing TANAPA’s capacity to enforce the law,” the project “increased the possibility of violent confrontations” between rangers and villagers. The Panel found the Bank to have failed to adequately supervise TANAPA and ignored rangers use of “excessive force,” in violation of international standards. Already over the course of the REGROW project, at least 11 individuals were killed by police or rangers, five disappeared, and dozens suffered physical and psychological harm, including torture and sexual violence.

“The murders of Mr. Igembe and Mr. Mhaki make it painfully clear that the Tanzanian government has no intent to end atrocities against local communities for tourist revenue. These brutal actions not only constitute abject crimes but are also a blatant violation of the commitments the government made to the World Bank,” said Anuradha Mittal, Executive Director of the Oakland Institute. “The Bank created a monster in TANAPA and must be held accountable along with the rogue ranger force,” Mittal added.

In its April 2, 2025 press release, the World Bank stated that “The Government of Tanzania has committed to implementing the MAP [Management Action Plan], and the World Bank will support and supervise its implementation.” The Action Plan is based on the premise that the government will honor its now broken promise that there will be no resettlement and villagers can continue their livelihood activities, like grazing and fishing. Iyala village, where Mr. Igembe was killed, is one of the five villages consumed by the October 2023 expansion of Ruaha National Park.

The Bank also committed to addressing violence by TANAPA rangers through a grievance mechanism and trainings on “relevant good international practice in protected area management.” Unfortunately, the Oakland Institute’s warning to the Bank’s officials, that given the extent of TANAPA’s human rights abuses, these measures would fail in preventing future harms, has come true.

“The violence hasn’t stopped. Villagers are being killed, their cattle stolen, their lives destroyed. Local communities are desperate for the world to listen. The Oakland Institute joins them in demanding that the World Bank take responsibility and act now. Every day of silence costs lives. The victims and their families deserve justice, truth, and the chance to live without fear,” concluded Mittal.

Source:The Oakland Institute

Related posts:

The World Bank Must Be Held Accountable for Harm Inflicted on Tanzanian Communities by Tourism Project

The World Bank Must Be Held Accountable for Harm Inflicted on Tanzanian Communities by Tourism Project

Campaign Victory: World Bank Suspends Funding for REGROW, a Conservation Project Responsible for Evictions & Human Rights Abuses in Tanzania

Campaign Victory: World Bank Suspends Funding for REGROW, a Conservation Project Responsible for Evictions & Human Rights Abuses in Tanzania

URGENT ALERT: Tanzanian Government on a Rampage Against Indigenous People

URGENT ALERT: Tanzanian Government on a Rampage Against Indigenous People

NGO WORK

Defending rights and realising just economies: Human rights defenders and business (2015-2024)

Published

2 months agoon

May 22, 2025

Over the past decade, human rights defenders (HRDs) have courageously organised to stop corporate abuse and prevent business activities from causing harm – exposing human rights and environmental violations, demanding accountability, and advocating for rights-respecting economic practices. From Indigenous Peoples protecting forests from mining activities to journalists exposing health and environmental harms related to logging to workers advocating for better conditions in the garment sector, HRDs are at the forefront of creating a more equitable, sustainable and abundant world where rights are protected, people and nature thrive, and just economies can flourish.

Every one of us has the right to take action to protect our rights and environments and contribute to creating a more just and equitable world, and yet those who do often face great risk. Businesses have the responsibility to respect human rights, including the right of all people to defend human rights. When companies fail to listen to HRDs, they lose important allies – people and groups fighting for transparency and accountability, and against corruption, which are all essential elements of an open and stable business operating environment. With authoritarianism on the rise, the imperative of realising a just global energy transition, and deepening inequality around the world, the role of business has rarely been so important – especially as HRDs pressing for rights-respecting corporate practice face increasing challenges.

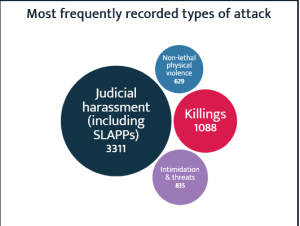

From January 2015 to December 2024, the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (the Resource Centre) recorded more than 6,400 attacks across 147 countries against people who voiced concerns about business-related risks or harms. This is close to two attacks on average every day over the past ten years. In 2024 alone, we tracked 660 attacks.

Civic space – the environment that enables all of us to organise, participate, and communicate freely in our societies – has also continued to deteriorate over the past decade. According to Civicus, only 3.6% of the world’s population currently lives in countries with open civic space, where citizens and civil society organisations are able to organise, participate and communicate without restrictions. In every region, governments have abused their power to limit the civic freedoms of people advocating for responsible business practice by detaining journalists, passing restrictive legislation (such as foreign funding bills and critical infrastructure laws), criminalising and prosecuting HRDs, and using violent force at protests, among other actions.

This is harmful for business. Civic space restrictions create an ‘information black box,’ leaving companies and investors with gaps in knowledge about potential or actual negative human rights impacts, which can lead to legal, financial, reputational and other risks. Democracy and full enjoyment of civic freedoms are central to addressing the key challenges humanity faces and to sustainable economic growth – some economists have found that democratisation causes an increase in GDP per capita of between 20% and 25%. In addition, under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) and subsequent guidance, business actors also have a responsibility to respect human rights, which includes engaging in robust human rights due diligence that identifies and mitigates risks to civic freedoms and HRDs.

In our current context of continued erosion of democracy, deregulation, backlash against environmental, social and governance (ESG) concerns, increased conflict, and the weaponsation of both law and technology against human rights defence, HRDs remind us to transcend polarisation and persist in realising a more just and abundant future for us all. Key wins over the past decade include a legally binding instrument to protect environmental defenders, regulations to curb strategic lawsuits against public participation, and important victories advancing corporate accountability following advocacy and judicial efforts. Representatives from Indigenous communities have shared a powerful vision for a rights-respecting energy transition – an essential framework for the future. They are innovating, at times together with progressive businesses, to bring about transformative new business models designed to deliver shared prosperity in alignment with Indigenous Peoples’ self-determined priorities.

Between January 2015 and December 2024, the Resource Centre documented more than 6,400 cases of attacks globally against HRDs challenging corporate harm. These attacks were against Indigenous Peoples, youth leaders, elders, women defenders, journalists, environmental defenders, communities, non-profit organisations and others, negatively affecting tens of thousands of people.

This is just the tip of the iceberg. Our research is based on publicly available information, and given the severity of civic space restrictions in some countries and security concerns, many attacks go unreported. In addition, governments are largely failing in their duty to monitor attacks. In countries and regions where few attacks are documented, this does not mean that violence against defenders is nonexistent, but rather that the information is not accessible. Learn more about our research methodology.

Restrictions on civic space helped to facilitate these attacks. Other drivers included weak rule of law and unaccountable governance, economic models focused on profit maximisation through unsustainable resource extraction, racism and discrimination, and lack of consultation with potentially affected stakeholders.

“I routinely hear from Indigenous defenders working in isolated, remote or rural areas that businesses and governments do not consult with them properly – and that their right to give or withhold their free, prior and informed consent for activities negatively affecting their lives or their territories is either manipulated or ignored. Some attacks are committed by agents acting for businesses, others by government authorities and businesses acting together.”

– Mary Lawlor, UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders

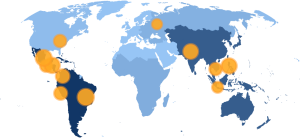

Latin America and the Caribbean and Asia and the Pacific have consistently been the most dangerous regions for HRDs raising concerns about corporate harm, accounting for close to three in four (71%) attacks in the past decade. Africa follows with 583 instances of attacks – close to a third of these occurred in Uganda.

In Latin America, the majority of attacks are concentrated in six countries that account for 35% of all attacks globally – Brazil (473), Mexico (455), Honduras (418), Colombia (331), Peru (299) and Guatemala (256). Despite comprising only 0.1% of the world’s population, 6.5% of attacks took place in Honduras. In Asia, the highest number of attacks occurred in the Philippines (411), India (385), Cambodia (279) and Indonesia (216).

Another trend is an increase in attacks in the United Kingdom, where 91% of attacks have been judicial harassment (arrests, criminal charges and SLAPPs). Attacks in the UK notably increased from seven in 2022 to 21 in 2023 – the same year the UK Government’s Public Order Act, which significantly increased the police’s power to respond to protests, came into force, undermining freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association. Attacks further increased in 2024 to 34. Almost all of these attacks were against people raising concerns about the fossil fuel sector.

Attacks target individuals, organisations and communities, causing physical harm, draining resources and obstructing human rights work. They can also have a chilling effect on civic space and weaken the social fabric vital for resista nce, community cohesion, and an inclusive and peaceful society. In addition to harming physical security, attacks can also negatively affect HRDs’ mental, emotional and economic well-being.

nce, community cohesion, and an inclusive and peaceful society. In addition to harming physical security, attacks can also negatively affect HRDs’ mental, emotional and economic well-being.

Since 2015, the Resource Centre has tracked 5,323 non-lethal attacks on HRDs challenging corporate harm.Through our research and collective work with the ALLIED Coalition, we have also identified numerous cases of escalations and cyclical attacks against HRDs where threats and judicial harassment precede physical violence.

Escalation of attacks: Tumandok Peoples’ opposition to dam project

Co-authored with ALLIED and ANGOC

The Tumandok People are an Indigenous group whose ancestral lands in the Philippines have been targeted for numerous private and public development projects, driving ongoing conflict for the community. Community members have actively opposed the Jalaur River Multipurpose Project (JRMP) II infrastructure project, which includes the construction of a dam that would displace Indigenous villages and proceed without their FPIC. Daewoo Engineering & Construction Co. Ltd was awarded the construction contract and the project is supported by Export-Import Bank of Korea.

Numerous attacks have been carried out against community members who voiced opposition to this project. This cyclical violence against the Tumandok is reflected in data from the Asian NGO Coalition for Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ANGOC), ALLIED and other sources.

We invited Export-Import Bank of Korea and Daewoo E&C to respond. Export-Import Bank’s full response to the killing of HRDs in December 2020 is available here. Daewoo E&C did not respond.

Killings and disappearances

Over the past decade, we documented close to 1,100 killings of HRDs who bravely spoke out against corporate harm. In 2024 alone, we recorded the murders of 52 people.

We commemorate the lives, courage and vital work of these HRDs and their communities. While governments have a duty to investigate these murders, the majority of attacks – both lethal and non-lethal – go uninvestigated and unpunished, fostering a culture of impunity that only emboldens further violence.

Indigenous defenders are particularly at risk. Close to a third (31%) of those killed were Indigenous defenders. Most of the killings of Indigenous defenders occurred in Latin America, as well as the Philippines.

We also tracked 116 abductions and disappearances, which leave families and communities bereft, in the dark as to the safety and whereabouts of their loved one. Most took place in Mexico and the Philippines.

Disappearence of two defenders in Mexico

Co-authored with Global Rights Advocacy

The mining sector is the most dangerous sector for HRDs in Mexico. Over the past decade, a quarter of attacks were against HRDs raising concerns about mining; 40% of those attacks were killings. In the coastal mountains of Michoacán, there is powerful resistance by Indigenous Peoples to mining, amidst a generalised atmosphere of violence. Indigenous Peoples are defending their territories against private interests and organised crime, facing criminalisation, persecution, aggression and killings.

Read full report: Business & Human Rights Resource Centre

Related posts:

Attacks fueled by governments’ double standards fail to deter human rights defenders

Attacks fueled by governments’ double standards fail to deter human rights defenders

Human rights defenders & business in 2022: People challenging corporate power to protect our planet.

Human rights defenders & business in 2022: People challenging corporate power to protect our planet.

Human rights defenders show remarkable courage in the face of attacks and killings – new report

Human rights defenders show remarkable courage in the face of attacks and killings – new report

#COP27: HUMAN RIGHTS ADVOCATES URGE PARTIES TO INCREASE RECOGNITION AND PROTECTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND LAND DEFENDERS.

#COP27: HUMAN RIGHTS ADVOCATES URGE PARTIES TO INCREASE RECOGNITION AND PROTECTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND LAND DEFENDERS.

Land Grabbing Crisis Escalates in Uganda: Mayiga Urges Citizens to Secure Land Documents

Seizing the Jubilee moment: Cancel the debt to unlock Africa’s clean energy future

Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

A decade of displacement: How Uganda’s Oil refinery victims are dying before realizing justice as EACOP secures financial backing to further significant environmental harm.

Activism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

Govt launches Central Account for Busuulu to protect tenants from evictions

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

- PRESENDIANTIAL DIRECTIVE BANNING ALL LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA

- FROM LAND GRABBERS TO CARBON COWBOYS A NEW SCRAMBLE FOR COMMUNITY LANDS TAKES OFF

- African Faith Leaders Demand Reparations From The Gates Foundation.

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS1 week ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS1 week agoActivism on Trial: Despite the increasing repressive measures, Uganda’s EACOP protesters are achieving unexpected victories in the country’s justice systems.

-

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks agoCommunities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

-

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS4 days ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS4 days agoSeizing the Jubilee moment: Cancel the debt to unlock Africa’s clean energy future

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days agoLand Grabbing Crisis Escalates in Uganda: Mayiga Urges Citizens to Secure Land Documents