MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Transgenic rice once again proposed as solution to bacterial blight outbreaks, this time in Africa

Published

2 years agoon

Scientists with an international rice initiative have been raising the alarm about a strain of bacterial blight causing outbreaks in rice fields in East Africa, and they say the patented transgenic varieties they have developed are the solution.

The scientists are with the Healthy Crops Project, a non-profit consortium funded by the Gates Foundation that brings together US and German universities, the French national research institute (IRD), the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and others. In a scientific article published in June 2023, the team claims to have identified an outbreak of a Chinese variant of bacterial blight in Tanzania, which was previously unknown on the continent, and then to have employed gene-editing techniques to confer broad resistance to bacterial blight in rice grown in Africa.

The scientists plan to first introduce their transgenic rice in Kenya, where recent regulations allow for the introduction of gene-edited crops. They have already crossed their resistant line with a variety called Komboka, which was developed by IRRI and the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation. While team leader Wolf Frommer told GRAIN they have “no interest in making profits from small scale producers”, he acknowledged that there is a patent on their gene-edited rice lines. He also said outbreaks of the Chinese bacterial blight strain have now spread to Kenya and Madagascar.

This is not the first time that IRRI and its partners have proposed GM rice as a solution to bacterial blight. Twenty years ago, farmer and consumer groups in Asia protested against the introduction of a rice known as “BB rice”— IRRI’s first transgenic rice to be field tested at its research centre in the Philippines. The Healthy Crops gene-edited rice varieties would be the first transgenic lines to be commercialised in Africa, if the project moves forward.

Groups in Asia that were opposed to IRRI’s “BB rice” argued that bacterial blight outbreaks are a product of IRRI’s green revolution model. The disease only began to be a major problem when IRRI’s semi-dwarf varieties were planted over large areas, replacing diverse local varieties with vast, uniform monocultures. The uniformity and reliance on huge amounts of chemical fertilisers created the ideal breeding grounds for bacterial blight and other diseases. IRRI’s response, beyond the promotion of chemical pesticides, was to try and integrate resistant genes from farmer varieties into its varieties, but this single gene resistance (or even multiple gene resistance) was inevitably overcome by the disease, leading to an endless race to try and identify and integrate new genes, and an escalation in pesticide use. Those opposing BB rice argued that the GMO rice would also not provide durable resistance, and that the only effective solution was to bring back diversity in the fields by restoring farmer seed systems and by moving away from chemical fertilisers and pesticides to practices that keep disease pressures down. IRRI never did manage to gain approval for the release of “BB rice” in Asia.

The situation is similar in Tanzania and Kenya. For decades now, farmers have resisted constant efforts by IRRI and other agencies to get them to abandon their farmer varieties and switch to the so-called high-yielding varieties (HYVs), including the Komboka variety of rice that the Healthy Crops team is now gene-editing. Farmer seeds still account for the vast majority of rice grown in Tanzania, one of the only countries in Africa that is self-sufficient in rice. This push for HYVs has been especially heavy in the “epicentre” of the recent bacterial blight outbreak identified by the Healthy Crops team: the Dakawa irrigation scheme in Tanzania’s fertile Morogoro Region.

It is noteworthy that the outbreak appears to have first affected fields planted to a variety called Saro 5, which has been promoted by numerous donors including the World Bank, USAID, AGRA and the Gates Foundation, despite its requirement for high levels of chemical fertilisers. For several years, the Norwegian fertiliser company Yara heavily promoted Saro 5, in combination with its fertilisers, under the Southern Agriculture Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT) programme. Saro 5 seeds were given out to farmers for free and were multiplied at the Chollima Rice Institute in Dakawa and distributed to farmers in other parts of the country. These different agencies and companies have thus spread a variety of rice highly susceptible to a new strain of bacterial blight across many farms in Tanzania, creating the conditions for the disease to amplify and spread.

Several rice farmers in Dakawa contacted by Tanzania’s national farmers’ organisation MVIWATA confirmed that the disease is present in their fields. They said that the government has been promoting Saro 5 to deal with the disease, but that this has failed dramatically, since Saro 5 is highly susceptible. “Saro 5 is the type of seed that is mostly affected,” says Saumini Hamisi, a rice farmer at Dakawa.

The farmers also said that the national research agency and the extension agents in the area have been telling farmers to use various pesticides against the disease, which has done nothing to help either.

Some speculate that this new strain of bacterial blight came to Dakawa via the Chinese province of Yunnan, since this strain of the disease is only found there. They say that infected material was likely brought over by the Chongqing Zhongyi Seed Company, which took over the Chinese Agro-technology Demonstration Centre built in Dakawa in 2009 with cooperation funds from China. Like the other foreign funded programmes at Dakawa, the Chinese initiative aimed to displace local varieties, in this case with Chongqing Zhongyi’s patented hybrid varieties. The Chinese seed company has not commented on these speculations, and did not respond to GRAIN’s inquiries either. The possibility raises serious concerns, given that Chinese seed companies are engaged in hybrid rice programmes in many other countries across Africa and the world.

But whether or not the Chinese seed company is the source, the disease is now spreading without it, as the Chinese project shut down last year. The question now is how to deal with the outbreak.

In Tanzania and other rice growing regions of the world, farmers have long managed bacterial blight and other diseases. Farmers in the Philippines with the farmer-scientist network MASIPAG, for instance, do regularly select for disease resistance within their farmer varieties of rice, but their main focus is not on breeding for resistance but in using farming practices that negate the factors that favour pest or disease population build-up and outbreaks. According to MASIPAG scientist and founding member, Dr. Chito Medina, this includes planting at least three different rice varieties on each farm “so that the differential resistance of each variety prevents the development and outbreak of any biotype or any continuous increase of population of any biotype or kind of pest or pathogen” (a technique that is also used to control rice diseases in Yunnan). They also deploy certain water management techniques and avoid the use of chemical fertilisers, especially nitrogen fertilisers, which increases the reproductive rate of insects and pathogens, including bacterial blight. Medina says that, because of this approach, “there have been no reports among MASIPAG farmers of any outbreaks or recurrent pest or disease problems for a long time”, despite the presence of many strains of bacterial blight across the country.

The local varieties favoured by farmers in East Africa may be susceptible to the bacterial blight strains now circulating in the region. But this does not have to lead to major crop losses. Rather than use the outbreak as another excuse to destroy farmer seed systems, efforts must focus on helping farmers to build up resistance within their local varieties through selection and seed sharing, and to utilise farming practices that can control the disease. It is bad enough that a foreign-funded programme brought a disease outbreak; it will be much worse if this paves the way for another foreign-funded programme to displace local varieties with patented, transgenic rice seeds.

Original Source: Grain.org

Related posts:

African Faith Communities Tell Gates Foundation, “Big Farming is No Solution for Africa

African Faith Communities Tell Gates Foundation, “Big Farming is No Solution for Africa

Uganda receives fertiliser for maize, rice farming

Uganda receives fertiliser for maize, rice farming

Cassava diseases threaten success of proposed ethanol plant

Cassava diseases threaten success of proposed ethanol plant

Food sovereignty is Africa’s only solution to climate chaos

Food sovereignty is Africa’s only solution to climate chaos

You may like

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

“Vacant Land” Narrative Fuels Dispossession and Ecological Crisis in Africa – New report.

Published

18 hours agoon

November 13, 2025

By Witness Radio team.

Over the years, the African continent has been damaged by the notion that it has vast and vacant land that is unused or underutilised, waiting to be transformed into industrial farms or profitable carbon markets. This myth, typical of the colonial era ideologies, has justified land grabs, mass displacements, and environmental destruction in the name of development and modernisation.

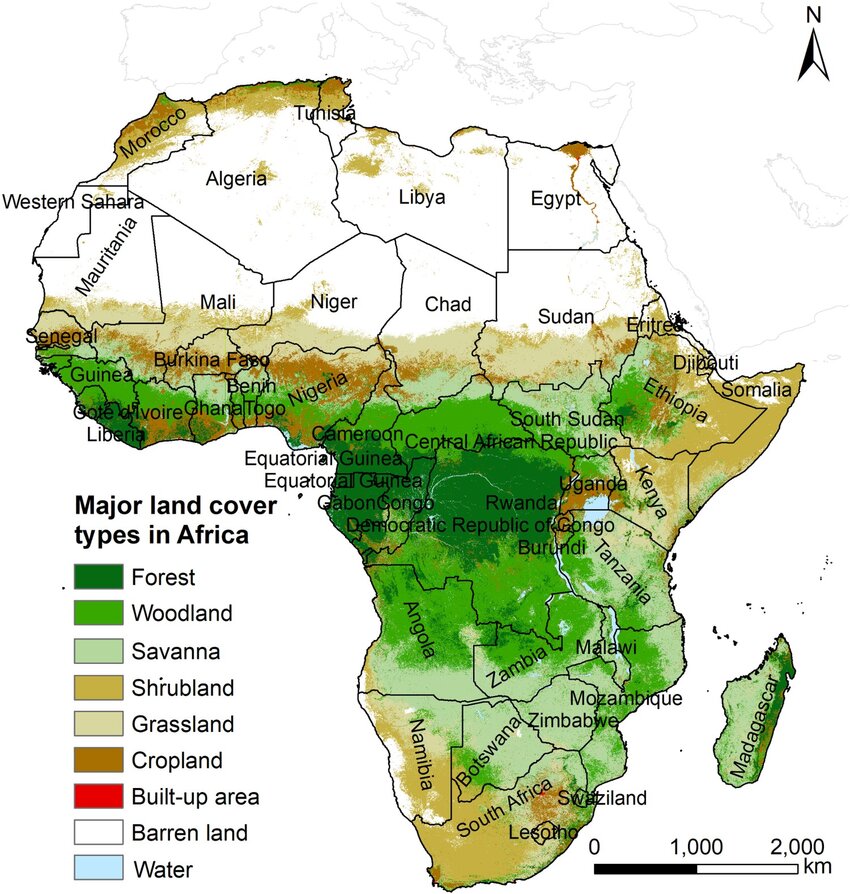

A new report by the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA) titled “Land Availability and Land-Use Changes in Africa (2025)” dismisses this narrative as misleading. Drawing on satellite data, field research, and interviews with farmers across Africa, including Zambia, Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, the study reveals that far from being empty, Africa’s landscapes are multifunctional systems that sustain millions of lives.

“Much of the land labelled as “underutilised” is, in fact, used for grazing, shifting cultivation, gathering wild foods, spiritual practices, or is part of ecologically significant systems such as forests, wetlands, or savannahs. These uses are often invisible in formal land registries or economic metrics but are essential for local livelihoods and biodiversity. Moreover, the land often carries layered customary claims and is far from being available for simple expropriation,” says the report.

“Africa has seen three waves of dispossession, and we are in the midst of the third. The first was the alienation of land through conquest and annexation in the colonial period. In some parts of the continent, there have been reversals as part of national liberation struggles and the early independence era. But state developmentalism through the post-colonial period also brought about a second wave of state-driven land dispossession.” This historical context is crucial to understanding the current state of land rights and development in Africa. Said Ruth Hall, a professor at the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAS), at the University of the Western Cape in Cape Town, South Africa, during the official launch of the report.

The report further underestimates the assumption that smallholder farmers are unproductive and should be replaced with mechanised large-scale farming, leading to a loss of food sovereignty.

“The claim that small-scale farmers are incapable of feeding Africa is not supported by evidence. Africa has an estimated 33 million smallholder farmers, who manage 80% of the continent’s farmland and produce up to 80% of its food. Rather than being inefficient, small-scale agro-ecological farming offers numerous advantages: it is more labour-intensive, resilient to shocks, adaptable to local environments, and embedded in cultural and social life. Dismissing this sector in favour of large-scale, mechanised monocultures undermines food sovereignty, biodiversity, and rural employment.” Reads the Report.

The idea that industrial agriculture will lift millions out of poverty has not materialised. Instead, large-scale agribusiness projects have often concentrated land and wealth in the hands of elites and foreign investors. Job creation has been minimal, as modern farms rely heavily on machinery rather than human labour. Moreover, export-oriented agriculture prioritises global markets over local food security, leaving communities vulnerable to price fluctuations and shortages.

“The promise that agro-industrial expansion will create millions of decent jobs is historically and economically questionable. Agro-industrial models tend to displace labour through mechanisation and concentrate benefits in the hands of large companies. Most industrial agriculture jobs are seasonal, poorly paid, and insecure. In contrast, smallholder farming remains the primary source of employment across Africa, particularly for young people and women. The idea that technology-intensive farming will be a panacea for unemployment ignores the structural realities of African economies and the failures of previous industrialisation efforts.”

Additionally, the assumption that increasing yields and expanding markets will automatically improve food access overlooks the structural causes of food insecurity. People’s ability, particularly that of the poor and marginalised, to access nutritious food depends on land rights, income distribution, gender equity, and the functioning of political systems. In many countries, high agricultural productivity coexists with hunger and malnutrition because food systems are oriented towards export and profit rather than equitable distribution and local nourishment. It highlights the urgent need for equitable food distribution, making the audience more empathetic and aware of the issue.

Furthermore, technological fixes such as improved seeds, synthetic fertilizers, and irrigation are being promoted as solutions to Africa’s food insecurity, but evidence suggests otherwise. The Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) spent over a decade pushing such technologies with little success; hunger actually increased in its target countries.

These high-input models overlook local ecological realities and structural inequalities, while increasing dependence on costly external inputs. As a result, smallholders often fall into debt and lose control over their own seeds and farming systems. It underscores the importance of understanding and respecting local ecological realities, making the audience feel more connected and responsible.

Africa is already experiencing an increased and accelerating squeeze on land due to competing demands including rapid population growth and urbanisation, Expansion of mining operations, especially for critical minerals like cobalt, lithium, and rare-earth elements, which are central to the global green transition, The proliferation of carbon-offset projects, often requiring vast tracts of land for afforestation or reforestation schemes that displace existing land users, Rising global demand for timber, which is increasing deforestation and land competition as well as Agricultural expansion for commodity crops, including large-scale plantations of palm oil, sugarcane, tobacco, and rubber.

“In East Africa, we see mass evictions, like the Maasai of Burunguru, forced from their ancestral territories in the name of conservation and tourism. In Central Africa, forests are cleared for mining of transitional minerals, destroying ecosystems and livelihoods. Women, a backbone of Africa’s food production, remain the most affected, and least consulted in decisions over land and resources and things that affect them.” Said Mariam Bassi Olsen from Friends of the Earth Nigeria, and a representative of the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa.

The report urges a shift away from Africa’s high-tech, market-driven, land-intensive development model toward a just, sustainable, and locally grounded vision by promoting agroecology for food sovereignty, ecological renewal, and rural livelihoods, while reducing the need for land expansion through improved productivity, equitable food distribution, and reduced waste.

Additionally, a call is made for responsible urban planning, sustainable timber management, and reduced mineral demand through circular economies, as well as the legal recognition of customary land rights, especially for women and Indigenous peoples, and adherence to the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) for all land investments.

Related posts:

AGRA’s Silent Takeover: The Hidden Impact on Africa’s Agricultural Policies.

AGRA’s Silent Takeover: The Hidden Impact on Africa’s Agricultural Policies.

63 million people food insecure in Horn of Africa: report

63 million people food insecure in Horn of Africa: report

African Food Systems Summit 2024: Do not use it to promote failed agricultural models – African Faith Leaders.

African Food Systems Summit 2024: Do not use it to promote failed agricultural models – African Faith Leaders.

Carbon offset projects exacerbate land grabbing and undermine small farmers’ independence – GRAIN report

Carbon offset projects exacerbate land grabbing and undermine small farmers’ independence – GRAIN report

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Uganda’s Army is on the spot for forcibly grabbing land for families in Pangero Chiefdom in Nebbi district.

Published

21 hours agoon

November 13, 2025

By the Witness Radio team.

Despite the challenges, the community in Koch Parish, Nebbi Sub-County, in Nebbi District, near the Congolese border, has shown remarkable resilience. The Army seized approximately 100 acres of land, including private buildings, that members of the local Koch community had used for over 150 years to establish an Army barracks. Their resilience in the face of such a significant loss is genuinely inspiring.

The UPDF, as described on its website, is a nonpartisan force, national in character, patriotic, professional, disciplined, productive, and subordinate to the civilian authority as established under the constitution. Furthermore, it states that its primary interest is to protect Uganda and Africa at large, providing a safe and secure environment in which all Ugandan citizens can live and prosper.

However, according to a whistleblower, when the UPDF seized their land, no military chiefs offered prior communication, consultation, compensation, or resettlement. Instead, Uganda’s national Army only occupied people’s land forcefully, and not even the section commanders offered an official explanation.

“Citizens just woke up to a massive Army deployment in their fields,” wrote a whistleblower in an exchange with Witness Radio.

The occupied area in Koch Parish is not just a piece of land, but a home to the members of the Pangero chiefdom. This community belongs to the Alur kingdom, which spans north-western Congo and western Uganda, north of Lake Albert.

The reality and daily life of the Pangero community, which typically lives in a closely connected and communal manner, have been significantly impacted by the loss of both private and communal land. Not only is the cultural identity associated with land and community life at risk, but access to cultural sites, such as the graves of ancestors, is now denied.

Members of the local community who resisted the unlawful seizure of their land were reported to have been harassed and defamed. Despite these challenges, they continue to fight for their rights, making negotiations with the UPDF significantly more challenging.

Beyond the human suffering, the takeover also raises serious legal questions under Ugandan land law. Under Ugandan law, this action by the UPDF constitutes an illegal act. In principle, the government and, by extension, the Army are entitled to take over land if it is in the public interest, and are subject to fairly compensating the landowners.

However, this is subject to the condition that their intention is clearly communicated in advance and that negotiations take place with the previous residents, resulting in a mutual agreement on the necessary and appropriate compensation.

When faced with community resistance, the Army was compelled to conduct a survey and valuation of the land occupied by the UPDF in 2023 and 2024. However, land defenders in the area claim that the process was marred by irregularities in some cases, against the will and in the absence of many landowners.

“The community was also pressured by the Koch Land Committee responsible for the review. Despite that it was supposed to represent the local population, it was not democratically elected by consensus, as is tradition in Alur communities, and was comprised of an imposed elite.” A local defender told Witness Radio

At an announcement meeting facilitated by officials from the UPDF Land Board, their national surveyor, and the Commander of Koch Army Barracks on September 19, 2025, community members were compelled to sign documents for meager compensation for land that had been seized five years prior.

“Residents whose land was surveyed before were given two choices: To sell their land to the Army by accepting the offered compensation, or to refuse the UPDF’s offer. In the latter case, however, it would be necessary to contact the Army headquarters in Mbuya, which is far away, to assert one’s claims or submit a petition.” Says another defender. Despite signing for this money, as of the writing of this article, the community claims it had never received it, almost two months later.

Mr Opio Okech, who attended the meeting himself, disapproves that this equates to a forced decision to sell, as the further necessary measures seem almost impossible for those affected without legal knowledge or external support.

“The problem here from the government was to enter upon the land, stay for long without adequate awareness creation, then decide we are going nowhere. Come for compensation. This looks, smells, and walks like a forceful eviction, “he mentions.

The effects of forced land acquisition by the UPDF in Koch Parish pose a high risk of home and landlessness, rises in youth criminality, and recurring poverty, primarily affecting women and children. Furthermore, the dispersal of the traditional community of the Pangero chiefdom is most likely to result in a severe loss of cultural heritage.

The Ugandan government has a duty here to look after the needs of this traditional community beyond compensation. This could include providing alternative land on which the traditional communal way of life could continue.

Witness Radio had not received a response from Army spokesperson Mr. Felix Kulayigye regarding the land grab, despite several attempts. However, since the initial takeover in 2020, another land grab by the same agency is looming in the same Kochi community for the expansion of the Army barracks.

According to sources, the UPDF intends to acquire more than 1,000 acres in total, nearly half of Koch Parish, leaving residents in fear and uncertainty.

“People are now panicking because they have heard speculations that more land is being

targeted for expansion. They are concerned about the impunity of the national Army, since the land that was grabbed five years ago has not been paid for, and now there are reports that more than 1,000 acres of community land are being targeted.” Mr. Okello further revealed.

The fate of the Pangero chiefdom is not an isolated case. Across Uganda, communal lands belonging to traditional clans and kingdoms continue to face similar threats from investors and state actors. Although Ugandan law recognizes customary ownership, enforcement often remains weak, and those affected rarely have access to the information or resources needed to defend their rights.

Related posts:

Church of Uganda’s call to end land grabbing is timely and re-enforces earlier calls to investigate quack investors and their agents fueling the problem.

Church of Uganda’s call to end land grabbing is timely and re-enforces earlier calls to investigate quack investors and their agents fueling the problem.

Ugandan army to punish soldiers for torturing Journalist in Kampala

Ugandan army to punish soldiers for torturing Journalist in Kampala

Mubende district police are aiding land grabbing and committing crimes against locals they are obliged to protect.

Mubende district police are aiding land grabbing and committing crimes against locals they are obliged to protect.

Uganda: World Bank financing is violently forcing thousands of local families off their land for large-scale cereal growing.

Uganda: World Bank financing is violently forcing thousands of local families off their land for large-scale cereal growing.

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Seed Sovereignty: Most existing and emerging laws and policies on seeds are endangering seed saving and conservation on the African continent.

Published

3 days agoon

November 11, 2025

By the Witness Radio team

In Africa, farmers and civil society organizations are urgently warning about the adverse effects of existing policies on agrobiodiversity. These policies aim to erode centuries-old traditions of seed saving and exchange, effectively undermining seed sovereignty and intensifying dependency on commercial seed companies.

The struggle over seed sovereignty, particularly the rights of smallholder farmers, has become one of the most pressing issues for the continent’s agricultural future. As governments introduce new seed laws, such as the proposed East African Seed and Plant Varieties Act Bill of 2024, the preservation of cultural seeds and the rights of smallholder farmers are at stake.

The Communications and Advocacy Officer at Kenya’s Seed Savers Network, Tabitha Munyeri, notes that this has heightened monoculture, thereby significantly reducing the focus on indigenous plant varieties.

“There’s a lot of loss of agrobiodiversity with people focussing on a few foods, a few crops, leaving out so many other essential crops that have sustained humankind for generations and it is also important because it is coming at a time where we are having a lot of also conversations around different seed laws that are coming up for example within the EAC we see that there is the seed and plant varieties bill of 2024 and we are looking at it as a huge setback and there is need for us to create awareness around even the policies that exist.”

She further argues that there is a need to raise awareness and sensitise farmers to the existing policies so that they can understand their effects on agrobiodiversity.

“Even for Kenya we have been having punitive seed laws for the longest time but now we are happy that courts of law are reviewing the law, but we still think that there is need to create a lot of advocacy around the seed laws and what they really mean to farmers because some of them do not understand, some of them are not even interested but once they get to know what it means and the impacts that the laws have on them then they are also able to become more vocal and more involved in the process.” She says.

Farmers in Africa have been the custodians of agricultural biodiversity, developing and maintaining numerous varieties of crops that are suited to local soils and climates. However, over the last few decades, the focus on farming has drastically declined to a handful of “high-yield” crops and imported hybrid varieties, leaving out the diverse indigenous seeds that have sustained communities through droughts, pests, and diseases.

Munyeri warns that this decline in agrobiodiversity is accelerating, driven not merely by market pressures, but by restrictive laws that criminalise and discourage traditional seed-saving practices.

In Kenya, where smallholder farmers supply more than 80 percent of the country’s food, seed systems have long depended on the informal exchange of seeds within communities. Small-hold farmers have relied on these systems to share, adapt, and innovate with seeds suited to their local conditions. However, existing laws have tended to favour the formal sector, requiring seed certification, variety registration, and compliance with intellectual property protections that most small-scale farmers cannot afford.

The 2024 Seed and Plant Varieties Act Bill, currently under discussion in several East African countries, has sparked significant controversy. It seeks to modernize agriculture and align national systems with international standards. However, smallholder farmers and critics contend that it allows corporate control over genetic resources, limiting farmers’ autonomy and threatening biodiversity. Under such a framework, only registered seed varieties can be legally traded or exchanged, effectively outlawing the informal seed networks that have sustained rural communities for centuries.

If smallholder farmers lose their rights to exchange and cultivate indigenous varieties, they may also lose control over their food systems. Dependence on improved seeds necessitates purchasing new stock each planting season, eroding self-reliance and increasing vulnerability to market fluctuations.

This awareness gap is what the Seed Savers Network hopes to address. Through training programs and advocacy initiatives, including its recently concluded regional boot camp, the organization equips participants from across Africa with knowledge about seed laws, biodiversity, and policy engagement.

Related posts:

Seed Boot Camp: A struggle to conserve local and indigenous seeds from extinction.

Seed Boot Camp: A struggle to conserve local and indigenous seeds from extinction.

The EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025, is a potential threat to smallholder farmers, as it aims to disengage them from the agriculture business, according to experts.

The EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025, is a potential threat to smallholder farmers, as it aims to disengage them from the agriculture business, according to experts.

CSOs and Smallholder farmers are urgently convening to scrutinize the EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025.

CSOs and Smallholder farmers are urgently convening to scrutinize the EAC Seed & Plant Varieties Bill, 2025.

African governments are giving in to corporate pressure and undermining local seed systems – report

African governments are giving in to corporate pressure and undermining local seed systems – report

“Vacant Land” Narrative Fuels Dispossession and Ecological Crisis in Africa – New report.

Uganda’s Army is on the spot for forcibly grabbing land for families in Pangero Chiefdom in Nebbi district.

Climate wash: The World Bank’s Fresh Offensive on Land Rights

Africa’s Land Is Not Empty: New Report Debunks the Myth of “Unused Land” and Calls for a Just Future for the Continent’s Farmland

StopEACOP Coalition warns TotalEnergies and CNOOC investors of escalating ‘financial and reputational’ Risks

New! The Eyes on a Just Energy Transition in Africa Program is now live on Witness Radio.

Failed US-Brokered “Peace” Deal Was Never About Peace in DRC

Know Your Land rights and environmental protection laws: a case of a refreshed radio program transferring legal knowledge to local and indigenous communities to protect their land and the environment at Witness Radio.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

- PRESENDIANTIAL DIRECTIVE BANNING ALL LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoReport reveals ongoing Human Rights Abuses and environmental destruction by the Chinese oil company CNOOC

-

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks agoThe Environmental Crisis Is a Capitalist Crisis

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoLands ministry rejects call to save over 300 Masaka residents facing eviction

-

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks agoGlobal use of coal hit record high in 2024

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days agoSeed Sovereignty: Most existing and emerging laws and policies on seeds are endangering seed saving and conservation on the African continent.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK18 hours ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK18 hours ago“Vacant Land” Narrative Fuels Dispossession and Ecological Crisis in Africa – New report.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK21 hours ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK21 hours agoUganda’s Army is on the spot for forcibly grabbing land for families in Pangero Chiefdom in Nebbi district.

-

NGO WORK2 days ago

NGO WORK2 days agoDiscover How Foreign Interests and Resource Extraction Continue to Drive Congo’s Crisis