Opinion: Why we cannot celebrate the World Bank’s 80-year anniversary

The mothers and daughters of the global south cannot celebrate the World Bank’s 80-year legacy of harm.

This July, the World Bank Group celebrates its 80th anniversary. But for us — women rights defenders from Asia, Africa, and Latin America — there is nothing to celebrate.

While the World Bank is proudly presenting its successes in fighting poverty and building a greener future, the stories of communities in our countries paint a very different picture. From recent controversial projects to old ones where communities never found justice, the World Bank has a 80-year legacy of harm and impoverishment.

The negative impact of development projects can be long lasting. In 1985, the World Bank funded the Kedung Ombo Dam in Indonesia. Over 27,000 people were forcibly and violently evicted, with the military threatening those trying to resist. Forty years later, the harm inflicted remains unaddressed. Resettled women don’t have close access to water sources, health facilities, and a market. Pregnant women have failed to get checkups, while children have often dropped out of school and are being forced into early marriages.

Yet, despite acknowledging the harm it caused, the World Bank keeps replicating old mistakes.

In 2022, a community in Cameroon filed a complaint raising serious concerns about the World Bank-funded Nachtigal hydroelectric project, one of the largest dams in Central Africa. Imposed without people’s participation, the project is destroying livelihoods, taking lands, causingdeforestation, and destroying sacred sites. Our Cameroonian sisters are particularly affected: They have lost access to the forests where they used to pick medicinal herbs and other key natural resources. The complaint process has come to an end, but the hopes for justice are extremely limited. The investigations conducted by the bank’s accountability mechanisms are known to be extremely lengthy — and only rarely lead to some remedy.

Civil society has been calling on the World Bank Group to strengthen its safeguards and accountability mechanisms, which are currently falling short of a human rights-based approach. But for every step forward, there has been a step back. Moreover, safeguards have often been used as a pretext to protect the institution from the international human rights legal system and to avoid applying more stringent standards.

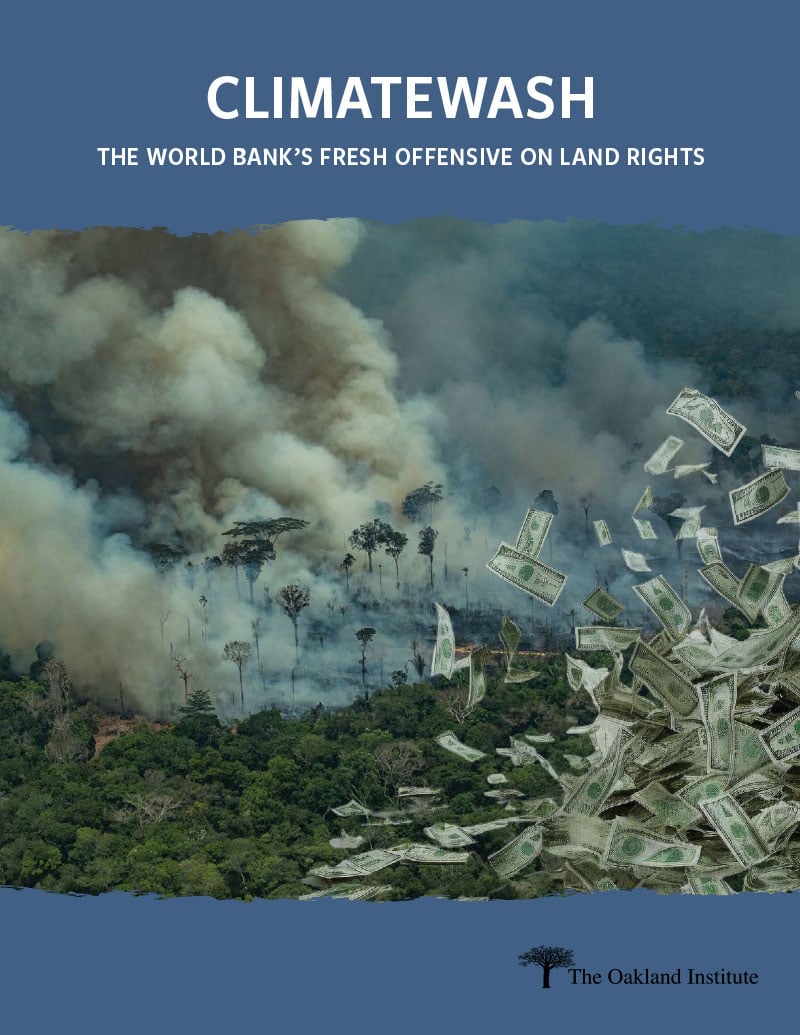

Under its new president, Ajay Banga, the World Bank has been undertaking a series of reforms, to become bigger and bolder in its response to climate change. But the bank’s actions appear to indicate more of the same. Beyond the catchy slogans, the World Bank is still replicating a top-down and neocolonial development model that ends up exacerbating the exact problems the bank claims to solve. For example, in Indonesia the World Bank Group — despite its pledges to address climate change — is funding the expansion of the Java 9 and 10 plants, considered the largest and dirtiest coal plants in Southeast Asia.

In its 80 years of existence, it is our view, as shared with other civil society groups, that the World Bank has fueled the spiraling debt crisis, growing inequality, and climate change, with a disproportionate impact on women and children. Some stories — like the scandal of the child sex abuse case in Kenyan schools funded by the World Bank — have hit the headlines. Others, unfortunately, have remained largely unreported.

Last year, the International Finance Corporation — the World Bank’s private arm — approved a $180 million loan to Allkem, for its Sal de Vida lithium mining project in Argentina’s Salar del Hombre Muerto. On paper, this investment falls under the bank’s green portfolio, because lithium is needed for the electric car batteries. In reality, this project has a catastrophic environmental impact, dried up one of the most important rivers in the area,, and violates the rights of the local Indigenous communities.

“If bank President Banga wants the institution to grow bigger, it should learn from the past as it looks forward.”

Before the project was approved, local communities and civil society organizations had sounded the alarm bell. They had prepared briefings on the project’s impacts and engaged with IFC to raise their concerns. But despite being recognized as “beneficiaries,” local communities say they are routinely ignored or silenced. The bank approved the loan without the community’s consent and did not take any action when local activists were threatened and criminalized.

As women defenders and caregivers, for generations we have been protecting our ecosystems sacrificed in the name of development and cared for our communities harmed under the pretext of economic growth. For generations, we have stood in solidarity with our sisters and brothers across the world who have been demanding a different type of development.

The World Bank cannot get it right by putting blinders on the past. The evicted Indonesian communities will not get their flooded land back. The women in Cameroon will not be able to access their precious medicinal herbs, as their forests have been cleared. And the Indigenous people in the Salar del Hombre Muerto lost their meadow near the river Trapiche, which dried up because of the huge volumes of fresh water used to extract lithium.

But the World Bank is still on time to withdraw from controversial new projects, to provide remedy to the harmed communities, to speed up the investigation processes, and to seek meaningful consent before building something. Eighty years are enough. If bank President Banga wants the institution to grow bigger, it should learn from the past as it looks forward.

Source: Devex