MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Restoring Our Land: Tackling Degradation for Climate Resilience, Food Security, and Sustainable Development at COP16

Published

1 year agoon

United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification

Land degradation is not just an environmental problem. It increases risks to human health and the spread of new diseases. It is a driver of forced migration and conflicts over scarce resources. It is a leading contributor to climate change, biodiversity loss, poverty, and food insecurity. In other words, it is at the core of sustainable development.

Restoring degraded land and soil, and investing in drought resilience, are some of the most cost-effective actions countries can take to reduce the high human, social and economic impacts of drought—simultaneously increasing food, water and energy security while reducing displacement and conflict drivers. Thirty years ago, with the adoption of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), countries agreed to walk together down this path.

What Drives Land Degradation and Desertification?

Land degradation is the long-term decline in the quality of land that leads to the reduction or loss of the biological or economic productivity of land. In the drylands, land degradation is known as desertification. According to the Global Land Outlook, drylands cover more than 45% of the Earth’s land surface, provide 44% of the world’s agriculture, support 50% of the world’s livestock, and are home to one in three people worldwide. Experts estimate that, if not reversed, land degradation will drive 700 million people out of their homes by 2050 because they will no longer be able to feed themselves or have access to sufficient water.

The dominant drivers of land degradation include agriculture and related land-use changes, unsustainable management or over-exploitation of resources, natural vegetation clearance, nutrient depletion, overgrazing, inappropriate irrigation, excessive use of agrochemicals, urban sprawl, pollution, mining and quarrying, among others.

Deforestation is one of the most significant causes of land degradation. Tree roots help bind soil particles, thus maintaining their quality. When trees are cut down, the soil particles tend to disperse, negatively impacting the quality of the soil.

Another driver of land degradation is a lack of land tenure security. When people own their land, they are more likely to make the long-term investments needed to sustainably manage land, such as practicing crop diversity and agroforestry. Even though land constitutes the main asset from which the rural poor derive their livelihoods, millions of farmers, especially women, do not own their land. In many countries, the laws or customs hinder women’s ownership of land. In more than 100 countries, women are dispossessed from their land when they lose their husbands. This is a key issue to global land restoration since women are more likely to invest in diverse food systems, which boost soil health, while men focus primarily on cash crops and monoculture.

What is the UN Convention to Combat Desertification?

In 1991, African environment ministers decided to prioritize their proposal for the negotiation of a new convention to combat desertification as one of the concrete recommendations to be adopted at the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED or Earth Summit) to be held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in June 1992. They hoped a convention would help them gain access to additional funding to combat desertification, land degradation, and drought.

Leading into the final days In Rio, delegates had reached agreement on much of the desertification chapter of Agenda 21, the UNCED outcome, including the definition of desertification: “Land degradation in arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas resulting from various factors, including climate variations and human activities.” However, there was still opposition to a convention. Many developing countries resisted the idea of a special convention for Africa, since they also faced land degradation. Industrialized countries maintained that desertification was a local problem and did not warrant a treaty. It wasn’t until the final hours of the Earth Summit that a deal was finally struck and the call for a convention was included in Chapter 12 of Agenda 21.

Negotiations on the Convention began in May 1993 and were completed in five meetings over fifteen months. At the first session in Nairobi, Kenya, the International Negotiating Committee held a one-week seminar to inform negotiators of the substantive issues related to desertification and drought, demonstrating that land degradation affected people around the world. This led to a serious discussion on how to create a global convention that still gave priority to Africa. When Committee Chair Bo Kjellén suggested including a special annex for Africa under the Convention, other regions insisted on annexes for their regions.

At the second meeting in Geneva, Switzerland, in September 1993, governments agreed to negotiate four annexes simultaneously, while giving special attention to Africa. In the end, the Convention includes regional implementation annexes for Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia, and the Northern Mediterranean. A fifth annex, for Central and Eastern Europe, was adopted in 2000.

Differences over financial resources nearly caused the negotiations to collapse. Developing countries called for a special fund as the centerpiece of the new convention. Industrialized countries rejected binding obligations to increase financial assistance to affected countries, insisting that existing resources could be used more effectively. The deadlock was broken only after the United States proposed establishing a “Global Mechanism” to improve monitoring and assessment of existing aid flows and increase donor coordination. Many developing countries were not happy, but believed they had to accept the Global Mechanism on the final night because if there was no agreement on finance, there would be no convention. On 17 June 1994, delegates adopted the UNCCD, four regional implementation annexes, and a resolution calling for urgent action for Africa.

The Convention recognizes the physical, biological, and socio-economic aspects of desertification and the importance of redirecting technology transfer so that it is demand-driven. The core of the convention is the development of national, subregional and regional action programmes by national governments in cooperation with donors, local populations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). In fact, the Convention was the first to call for the effective participation of local populations and organizations in the preparation of national action programmes. This innovation led the first “sustainable development” convention to also be referred to as a “bottom-up” convention.

The UNCCD was opened for signature in October 1994 and entered into force on 26 December 1996. Today, there are 197 parties, representing universal ratification.

Promoting Land Degradation Neutrality

In 2008, a group of scientists was asked by the UNCCD Executive Secretary to examine if the Convention could use the offsetting principle already practiced by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), and applied to deforestation at one site by planting trees elsewhere. The idea was to use this offsetting principle to lead to zero-net land degradation and expand the reach of the Convention to address land degradation globally, not just in the drylands.

The Secretariat and like-minded countries then advocated for endorsement of this concept of land degradation neutrality (LDN) by the UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) in June 2012 and its inclusion as one of the targets under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This would enable LDN to gain traction and effectively link land degradation as a driver of poverty, climate change and biodiversity loss, and demonstrate the relevance of productive land to global sustainability. The Rio+20 outcome, The Future We Want, highlights the need for urgent action to reverse land degradation and achieve a land-degradation neutral world.

After Rio+20, the UNCCD pushed forward with LDN on a variety of fronts. First, in 2013, the 11th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP) established a working group to develop a science-based definition of LDN (Decision 8/COP.11). In late 2014, the Secretariat set up the LDN pilot project, through which 14 affected countries worked to translate LDN into national targets.

Meanwhile, in New York, the UNCCD and its supporters successfully lobbied for including a target on LDN in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). When the 17 SDGs and 169 targets were adopted by the UN General Assembly in September 2015, they included target 15.3: “By 2030, combat desertification, restore degraded land and soil, including land affected by desertification, drought and floods, and strive to achieve a land degradation-neutral world.” For the first time, the UNCCD had successfully placed an item at the forefront of the international agenda.

The following month, UNCCD COP12 convened in Ankara, Turkey, and endorsed the science-based definition of LDN submitted by the working group:

“Land degradation neutrality is a state whereby the amount and quality of land resources necessary to support ecosystem functions and services and enhance food security remain stable or increase within specified temporary and spatial scales and ecosystems” (decision 3/COP.12).

And, in what some viewed as a ‘game changing’ accomplishment, COP12 agreed that striving to achieve SDG target 15.3 is a “strong vehicle for driving implementation of the UNCCD,” and invited countries to set voluntary targets to achieve LDN. The Global Mechanism and the UNCCD Secretariat established the LDN Target Setting Programme to assist countries in setting national baselines and creating voluntary national LDN targets and associated measures. Since then, 131 countries committed to setting LDN targets and more than 100 have already set their targets.

In 2017, the Convention’s Science-Policy Interface (SPI) published the Scientific Conceptual Framework for Land Degradation Neutrality, which provides a scientific foundation for understanding, implementing and monitoring LDN. It was designed as a bridge between the vision and the practical implementation of LDN by defining LDN in operational terms. The SPI developed three indicators, which created a clear pathway for monitoring LDN—both for the Convention and SDG 15.3:

- trends in land cover;

- trends in land productivity or functioning of the land; and

- trends in carbon stocks above and below ground.

But there were concerns. Some countries and members of civil society at COP12 were worried about the focus on LDN as a central UNCCD target. Some likened it to opening a door to land grabs and greenwashing. So while the UNCCD COP called for the restoration of 1.5 billion hectares of land by 2030 to achieve a land-degradation neutral world, it was also essential to acknowledge land rights and inclusive land governance arrangements at the national and sub-national levels. The land tenure decision at COP14 did just that.

Already countries have pledged to restore 1 billion hectares of land, but there is still more work to be done to make these pledges a reality.

2018-2030 Strategic Framework

In 2017, COP13 in Ordos, China, adopted the UNCCD 2018−2030 Strategic Framework, which has three main components: a vision, strategic objectives and an implementation framework.

The vision commits parties to “A future that avoids, minimizes, and reverses desertification/land degradation and mitigates the effects of drought in affected areas at all levels and strive to achieve a land degradation neutral world consistent with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, within the scope of the Convention.”

The Framework’s five strategic objectives are designed to guide the actions of all UNCCD stakeholders and parties until 2030:

- To improve the condition of affected ecosystems, combat desertification/land degradation, promote sustainable land management and contribute to land degradation neutrality

- To improve the living conditions of affected populations

- To mitigate, adapt to, and manage the effects of drought in order to enhance resilience of vulnerable populations and ecosystems

- To generate global environmental benefits through effective implementation of the UNCCD

- To mobilize substantial and additional financial and nonfinancial resources to support the implementation of the Convention by building effective partnerships at global and national level

The implementation framework defines the roles and responsibilities of parties, UNCCD institutions, partners and stakeholders in meeting the strategic objectives.

In Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, in 2022, COP15 launched a midterm evaluation of the Strategic Plan. The results of this evaluation, overseen by an intergovernmental working group, will be discussed at COP16, which is expected to adopt a decision on enhancing the implementation of the Strategic Framework for its final five years and restoring the necessary hectares of land to achieve a land degradation neutral world.

What’s Next?

UNCCD COP16 convenes in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, from 2-13 December 2024, under the theme “Our Land. Our Future.” The COP will commemorate the 30th anniversary of the UNCCD and a special segment will bring together leaders and high-level officials to commit to accelerate action to combat land degradation and desertification and improve drought resilience.

In addition to the midterm evaluation of the Strategic Plan and adopting the UNCCD’s biennial budget, COP16 is expected to negotiate and adopt decisions aimed at:

- accelerating restoration of degraded land between now and 2030;

- boosting drought preparedness, response and resilience;

- ensuring land continues to provide climate and biodiversity solutions;

- boosting resilience to sand and dust storms;

- scaling up nature-positive food production by protecting and restoring grasslands and rangelands;

- enhancing ongoing efforts to address desertification/land degradation and drought as one of the drivers that causes migration;

- strengthening women’s right to land tenure to advance land restoration; and

- promoting youth engagement, including decent land-based jobs for youth.

COP16 is also expected to catalyze new initiatives on land restoration and drought resilience that build on the G20 Global Land Initiative.

For the first time, the COP will include an Action Agenda, which will highlight voluntary commitments and actions and include thematic days:

- Land Day on 4 December will focus on the importance of healthy land for combating climate change, creating jobs and alleviating poverty, with an emphasis on nature-based solutions, land restoration, and private sector engagement.

- Agri-food System Day on 5 December will highlight sustainable farming practices for resilient crops and healthy soils while protecting ecosystems.

- Governance Day on 6 December will address inclusive land governance.

- People’s Day on 7 December will focus on the role of youth, women and civil society in decision-making.

- Science, Technology and Innovation Day on 9 December aims to accelerate scientific solutions for land health and resilience.

- Resilience Day on 10 December will focus on policies and technologies to build societal and planetary resilience in the face of climate change.

- Finance Day on 11 December will engage financial stakeholders to showcase innovative funding mechanisms and partnerships for land and drought resilience initiatives.

COP16 will also build upon the COPs of the CBD in October 2024 and the UNFCCC in November 2024, improving synergies between the three “Rio Conventions” and promoting the implementation of the SDGs.

As UNCCD Executive Secretary Ibrahim Thiaw said in his foreword to the second edition of the Global Land Outlook report, “Governments and stakeholders cannot stop the climate crisis today, biodiversity loss tomorrow, and land degradation the day after.” The international community needs to tackle all these issues together. Achieving climate, biodiversity and sustainable development goals is impossible without healthy land.

In 1994 the adoption of the UNCCD started the world down the path to reversing land degradation, desertification and drought. COP16 is expected to reaffirm this global commitment for present and future generations.

Pamela Chasek, Ph.D., is the Co-founder and Executive Editor of the Earth Negotiations Bulletin.

Original Source: Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB)

Related posts:

Protect family farming land to guarantee global food sovereignty and Climate change adaptation and mitigation – Global conference on Family Farming.

Protect family farming land to guarantee global food sovereignty and Climate change adaptation and mitigation – Global conference on Family Farming.

‘Her land, her rights’ a remedy for climate crisis

‘Her land, her rights’ a remedy for climate crisis

African Women forge bold actions for climate justice at the 2024 Women’s Climate Assembly in Senegal.

African Women forge bold actions for climate justice at the 2024 Women’s Climate Assembly in Senegal.

63 million people food insecure in Horn of Africa: report

63 million people food insecure in Horn of Africa: report

You may like

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Four hundred fifty victim families of the Oil Palm project in Buvuma are to receive compensation by this Friday – Witness Radio

Published

21 hours agoon

December 17, 2025

By Witness Radio team.

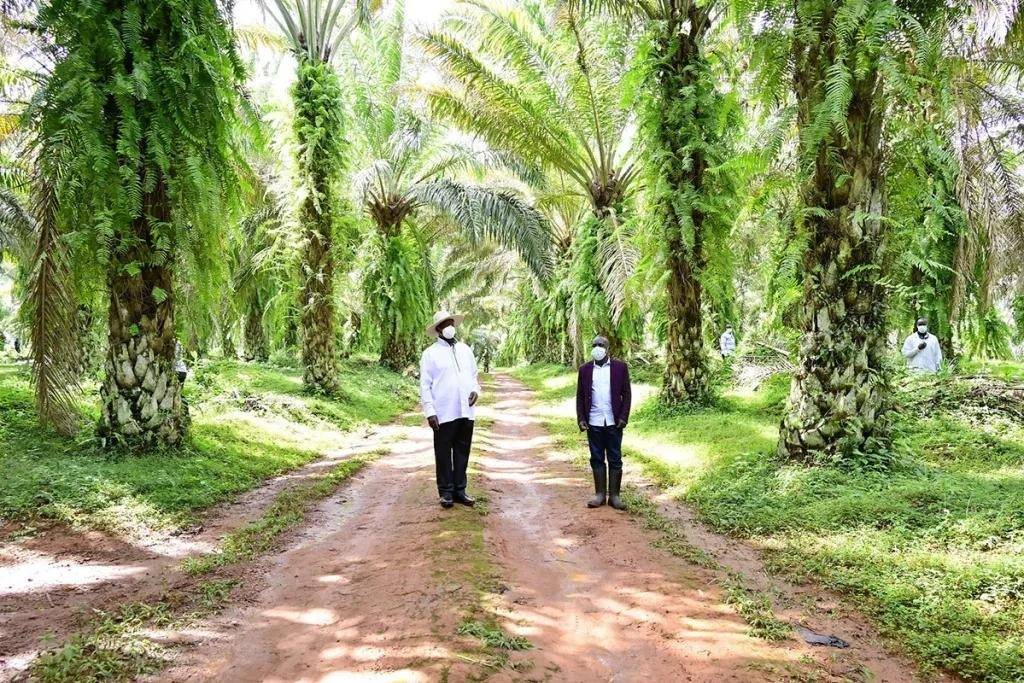

Entebbe, Uganda-President Yoweri Museveni has directed the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF) to compensate the oil palm Project immediately Affected Persons (PAPs) in Buvuma District, following a physical meeting with residents who had camped in Entebbe for nearly two weeks protesting delayed and selective compensation. The 450 victim families are part of over 1400 families that have lost their land to the oil palm project in Buvuma district.

The affected residents, numbering approximately 450, had sought the President’s intervention after being repeatedly excluded from the ongoing compensation process under the National Oil Palm Project (NOPP), despite earlier presidential directives on their compensation.

During the meetings on Friday and Saturday, community representatives told the President about prolonged delays, lack of transparency, and exclusion from compensation lists.

“We told the President about the back-and-forth his ministries have been sending us through, the lack of participation, and how we have been wrongly portrayed as people who do not own land when we do. Because he knows us, we reminded him of the directive he issued when he visited our area, which his ministries later claimed they were not aware of,” Witness Radio source highlighted.

President Museveni reportedly expressed surprise over the continued delays.

“I thought they had paid you. Why is it taking so long?” the President was quoted as saying during the meeting.

The President immediately directed MAAIF to work closely with the Office of the President to ensure that compensation is processed and paid without further delay.

According to the source, who attended the meeting, the President personally followed up on the matter.

“I have been directly talking to the President, and he told me that he is sending representatives from his office. He said he advised them to work with MAAIF to make sure we are compensated, and he wanted this to be done soon,” the source added.

While more than 200 residents had camped in Entebbe, the President advised them to select 20 representatives to ensure their voices are heard and that they feel included in the process.

“The President advised us to reduce to 20 people to represent the whole community since we knew what everyone wanted,” it added.

Following the President’s order, a joint meeting between representatives of the affected residents, MAAIF, and officials from the President’s Office was held yesterday in Entebbe.

It was resolved that compensation should be completed before Friday.

During the meeting and after reviewing relevant supporting documents, residents revealed that it was agreed that the government would compensate their group of approximately 450 affected persons with 16 billion Uganda shillings, which is intended to cover land loss, destroyed crops, and displacement caused by the oil palm project, clarifying how the funds will address their specific losses.

This directive comes close to two weeks after residents from Nairambi, Busamizi, Buvuma Town Council, and Buwooya Sub-counties camped in Entebbe, accusing government ministries of ignoring an earlier presidential order issued during the President’s June 18, 2025, visit to Buvuma District.

During that visit, the President had directed that all affected households be compensated and that 28 billion shillings be allocated, with 14 billion to be released immediately. However, six months later, many residents remained uncompensated, prompting renewed protests.

The compensation dispute dates back to 2018, when more than 100 residents sued the government and Bidco in Mukono High Court over forced evictions, delayed compensation, and lack of disclosure. The case was later transferred to Lugazi High Court.

During his June visit, the President advised the complainants to pursue an out-of-court settlement, promising faster compensation. This pledge, residents say, had not been honored until the latest intervention.

Even after the Ministry of Agriculture announced earlier this month that it would compensate oil palm-affected residents in Buvuma and Sango Bay, the group said it had not been consulted, prompting them to demand a meeting with the president.

As of publication, the affected residents say they are awaiting implementation of the President’s directive, hoping that the latest orders will finally bring an end to years of uncertainty and hardship.

“By Friday, we hope everything will have been processed because we submitted all the necessary supporting documents, and a team from the Office of the President is supervising the process,” it added.

According to a press statement from the Ministry, more than 11 villages are expected to benefit from the compensation exercise, indicating that many affected people are yet to be compensated. The statement revealed:

Based on the Government Valuers’ report, full payments have been made to 301 PAPs in five villages, and the Ministry plans to pay 1,405 PAPs across 11 villages.

When asked about the other communities that are not part of the initial 450 beneficiaries who ran to the president, the Ministry of Agriculture spokesperson, Ms. Connie Acayo, stated that the Ministry would follow due process, including clear criteria and verification steps, to ensure that all affected persons are identified and fairly compensated.

“Those people told us they do not want to hear about compensation procedures, valuation, or other processes associated with compensation; they only want the money. That is, maybe, why they went to the President. However, our Ministry is transparent, and we must follow established procedures when implementing such activities,” Connie told Witness Radio.

Related posts:

Uganda: Buvuma residents land cleared for oil palm growing before compensation

Uganda: Buvuma residents land cleared for oil palm growing before compensation

Tension as Project-Affected Persons demand to meet Uganda’s President over Oil Palm growing on their grabbed land.

Tension as Project-Affected Persons demand to meet Uganda’s President over Oil Palm growing on their grabbed land.

Palm Oil project investor in Landgrab: Witness Radio petitions Buganda Land Board to save its tenants from being forcefully displaced palm oil plantation.

Palm Oil project investor in Landgrab: Witness Radio petitions Buganda Land Board to save its tenants from being forcefully displaced palm oil plantation.

Oil palm growing: New twist as Buvuma residents disown group over compensation

Oil palm growing: New twist as Buvuma residents disown group over compensation

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Hidden iceberg: A new report identifies large scale industrial agriculture, livestock, and mining sectors as leading sources of attacks against land and environmental defenders worldwide.

Published

3 days agoon

December 15, 2025By Witness Radio team

A new global analysis report highlights a concerning rise in attacks against land and environmental defenders, aiming to inspire urgent policy and advocacy responses to this escalating violence.

The 2025 Hidden Iceberg Report reveals that nearly 2,500 non-lethal attacks against land and environmental defenders were documented across 75 countries in just two years. These attacks range from threats and surveillance to arbitrary arrests and online harassment.

The report findings by the Alliance for Land, Indigenous and Environmental Defenders (ALLIED), a global network of civil society actors that supports and protects Indigenous, Land, and Environmental Defenders, cover the period 2023-24, with Indigenous communities targeted in 1 out of every 3 cases.

According to the report, these attacks rarely make the news, yet they are often early warnings of lethal violence. Studies define lethal attacks as attacks designed to kill or cause serious harm, while non-lethal attacks aim to incapacitate or control a target temporarily.

As civic space continues to shrink worldwide, defenders and communities affected by development projects are increasingly silenced when defending their community rights or territorial land rights, which are often infringed upon by governments or project implementers.

“Every killing we document is preceded by multiple threats, intimidation attempts, and harassment, but states rarely report these cases. What we see publicly is only the tip of the iceberg.” The report mentions.

“We also saw in 2023 and 2024 that attacks against environmental concern groups expanded. Representing 10.7% of all attacks, the largest number of such attacks were registered in the United States, followed by Mexico, Uganda, and the United Kingdom.” Eva Hershaw, Global Data Lead at the International Land Coalition and Co-Chair of the ALLIED Data Working Group, revealed during the report launch.

The findings paint a stark picture where Latin America accounts for 58% of all documented non-lethal attacks, with Colombia, Guatemala, Brazil, Honduras, and Mexico emerging as persistent hotspots.

“Indigenous communities are attacked not because they are weak, but because they are powerful,” said Carla García, a legal expert from Guatemala. “They protect forests, rivers, and territories that governments and corporations want to exploit. Intimidation becomes a deliberate strategy to silence them.”

In Africa, violence against defenders takes gendered forms, with women facing online abuse, sexual violence, and social stigmatization.

“When women stand up against land grabbing or destructive projects, the attacks go beyond

threats. They target women’s dignity, their families, and their bodies. Many cases are never reported because the fear of retaliation is overwhelming,” Tawonga explained.

She adds that Environmental defenders in Africa are often brutalized by the very systems meant to protect them, making the reporting of attacks both risky and rare.

Across many African countries, environmental defenders operate in contexts characterized by state surveillance, intimidation, and harassment, with security legislation and cyber laws often used to silence them. On top of that, defenders are frequently stigmatized as anti-development or anti-investment. And this harmful narrative, usually pushed by governments and private actors, paints defenders as enemies of national progress.” She added.

One primary concern is the lack of reliable data on attacks, which should motivate policymakers and institutions to improve reporting mechanisms and foster accountability.

“This data gap is not accidental. It is the result of deep structural and systemic limitations that conceal the true scale of violence against environmental defenders here in Africa,” Tawonga explained.

The analysis identifies large‑scale industrial agriculture, livestock, and mining as the sectors most frequently targeted, guiding advocacy efforts toward these high-risk areas to enhance protective measures.

The defenders raising concerns about industrial agriculture and livestock operations were most consistently targeted. They faced the highest number of attacks, representing 29% of the total. We see that three out of every four attacks raising concerns about these business sectors were concentrated in Honduras, Colombia, Brazil, and Guatemala. After industrial agriculture and livestock, mining was the next most common sector connected with attacks.” Eva added

As the climate crisis deepens and competition over land intensifies, the report warns that attacks on environmental defenders will likely worsen unless governments, corporations, and international institutions act decisively.

The report calls on states to strengthen and sustain mechanisms for collecting and reporting data, support national human rights institutions with mandates to monitor violations, and commit to transparency regarding violence against defenders. It also urges businesses to adopt and implement public policy commitments that recognize and protect the vital role of human rights defenders.

Related posts:

Criminalization of planet, land, and environmental defenders in Uganda is on the increase as 2023 recorded the soaring number of attacks.

Criminalization of planet, land, and environmental defenders in Uganda is on the increase as 2023 recorded the soaring number of attacks.

Human rights defenders show remarkable courage in the face of attacks and killings – new report

Human rights defenders show remarkable courage in the face of attacks and killings – new report

African Development Bank’s Push for large scale Agriculture in Africa will spark more concerns over Food Sovereignty and Environmental Impacts.

African Development Bank’s Push for large scale Agriculture in Africa will spark more concerns over Food Sovereignty and Environmental Impacts.

Defending tomorrow: The climate crisis and threats against land and environmental defenders

Defending tomorrow: The climate crisis and threats against land and environmental defenders

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK

Women’s groups demand equality in land tenure security to boost food production.

Published

3 days agoon

December 15, 2025

By Witness Radio team.

Women’s struggle for land rights is now a critical global issue that has garnered attention from civil society organisations, policymakers, and human rights activists. Many argue that women are often excluded from land governance, hindering economic growth.

Statistics reveal that women produce a massive amount of the world’s food, especially in developing nations, with estimates often citing 60-80% of food in developing countries and roughly half globally. Recognizing this can inspire policymakers and activists to believe in women’s vital role in food security.

Edith Nalwende, a small-scale farmer from Bugiri district, is one of the many affected by the exclusion of women from land ownership and governance.

“Somebody called me, he was desperate and needed some quick money in his land. He told me I should buy this land, and I can pay by instalments. I informed my husband that there is a good deal here. I want to pay part of that money since the person is ready to receive the instalment. The response was obvious. Why do you want to buy land? Leave that land and don’t buy it,” she revealed in an interview with a Witness Radio journalist.

Many women like Nalwende face significant barriers to land ownership and recognition. Gender stereotypes in many Ugandan and African communities often bar women from owning land.

“Because of being a woman, I was stopped by my husband from buying land. I gave up. I didn’t buy the land. So, I called the seller. But he also didn’t appreciate why I told my husband, he asked me why I had told him,” said Nalwende.

ESAFF gathered rural women to share their stories. Edith was one of them, and women farmers were empowered to secure their land rights, thereby increasing productivity and promoting economic development.

While women are pivotal to small-scale agriculture, farm labour, and daily family subsistence, they face greater difficulty than men in accessing land and productivity-enhancing inputs and services. They claim they have been sidelined in issues of land governance, land ownership, and economic development.

According to research by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), less than 15 per cent of agricultural landholders worldwide are women, and 85 per cent are men. The most significant gender inequalities in access to land are found in North Africa and the Near East, where only around 5 per cent of all landholders are women.

Organised by the Eastern and Southern Africa Small-Scale Farmers Forum in Uganda (ESSAFF Uganda) and partners, the conference, attended by more than 40 small-scale women farmers and officials from various ministries, highlighted the critical role of women small-scale farmers in Uganda’s agriculture.

“Statistics show that women contribute the majority of agricultural labour in Uganda. Yet their contributions often remain undervalued and unsupported. Despite their central role, women continue to face systematic barriers to land ownership and control. Insecure land tenure undermines their productivity, limits their access to credit, and erodes their dignity.” Said Ms Christine Okumu, a representative from the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development

She adds that, “Without secure land rights, women cannot fully invest in sustainable farming practice. Nor can they pass assets to their children. This is a fact based on all the testimonies given before us here. Unless women have that right to land, they cannot fully invest in sustainable farming practice.”

It is estimated that if women small-scale farmers had the same resources as men, their yields could increase by 20–30%, significantly boosting food security.

“Closing this gender gap could add nearly $1 trillion to global GDP and lift 45 million people from hunger. Investing in women isn’t just about fairness – it’s key to Africa’s economic and agricultural future.” According to research by FAO.

Women’s land insecurity not only affects food sovereignty but also escalates gender-based violence, exposing women to rights violations and increased vulnerability.

“Insecure land tenure exposes women to heightened risk of gender-based violence. Dispossession, forced eviction, and land grabbing often come hand in hand with intimidation, harassment, and abuse. Such acts appear on social media platforms, accompanied by hurtful messages and embarrassing pictures. I’ve seen pictures of women being chased out of their homes. And I’ve seen also pictures of women who have invested in lands, and at the end of it all, because behind them, somebody took the land from them.” Added Ms Okumu.

Unlike other years, when the conference focused on topics like women in business and leadership, this year the focus has shifted to empowering women to own land, offering a hopeful path toward stronger agricultural independence.

“We are focusing on land so that we can support as many women as possible. And also, we would want to work together with the government, which has already rolled out a program of registration of land, and we think that this is something that women can take advantage of, so that they secure their land rights, and grow healthy food, and then also increase their income.” Says Ms Nancy Mugimba, the National Coordinator for ESSAFF Uganda.

She adds, “If you don’t have your own land, your ability to grow crops, generate income, and access financial services is limited. Securing land rights enables women to produce healthy food and invest in their communities.”

Ms Christine Okumu calls for the engagement of men and cultural and religious institutions in the fight for Women’s land rights, emphasizing that collective effort can lead to meaningful progress and social cohesion.

“The Ministry has also developed a strategy for male involvement. You know, this fight, we cannot do it alone. If we can get allies, it can help us. If we get a few men who can advocate for some of these issues and open the minds of other men to see that whatever they are doing is affecting their wives in a very negative way,” she said.

Related posts:

Forced Land Evictions in Uganda: Tenure and food insecurity on the rise…

Forced Land Evictions in Uganda: Tenure and food insecurity on the rise…

Chinese rice farm helps boost food security, employment in central Uganda

Chinese rice farm helps boost food security, employment in central Uganda

African Agriculture on a mission to boost global food production.

African Agriculture on a mission to boost global food production.

Agriculture sector allocated UGX 1.5 trillion to boost agro-production

Agriculture sector allocated UGX 1.5 trillion to boost agro-production

Four hundred fifty victim families of the Oil Palm project in Buvuma are to receive compensation by this Friday – Witness Radio

Britain, Netherlands withdraw $2.2 billion backing for Total-led Mozambique LNG

Hidden iceberg: A new report identifies large scale industrial agriculture, livestock, and mining sectors as leading sources of attacks against land and environmental defenders worldwide.

Women’s groups demand equality in land tenure security to boost food production.

Happening shortly! Kenya’s upcoming court ruling on the Seed Law could have a significant impact on farmers’ rights, food sovereignty, and the country’s food system.

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

EALA members renew push for unified sub-regional Agroecology Law during Mukono meeting.

Kenyan farmers secure right to share local seeds in court ruling

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

- PRESENDIANTIAL DIRECTIVE BANNING ALL LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks agoThe Carbon Mirage in Uganda: How reforestation initiatives are turning into sources of displacement and poverty?

-

WITNESS RADIO MILESTONES2 weeks ago

WITNESS RADIO MILESTONES2 weeks agoA Global Report reveals that Development Banks’ Accountability Systems are failing communities.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoUsing agroecology as a climate adaptation strategy and fighting extreme weather: A case of a retired teacher farming on a rocky terrain in Mukono, Uganda.

-

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks agoThe secretive cabal of US polluters that is rewriting the EU’s human rights and climate law

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days agoWomen’s groups demand equality in land tenure security to boost food production.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoExperts push for a National Bamboo Policy to strengthen climate mitigation efforts.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days agoTension as Project-Affected Persons demand to meet Uganda’s President over Oil Palm growing on their grabbed land.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoLand commission starts updating govt land countrywide.