SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

No Concession at PETAR: Combating Privatization is a Women’s Struggle in Brazil

Published

4 years agoon

This text comes out of conversations with women from the Ribeira River Valley who have devoted themselves to opposing the concession of one of the region’s most important parks. Their struggle is fundamental, and part of diverse resistances against the privatizing trend of creating ‘territories without people’. They remind us that their territory has been and is rooted in their stories, voices and resistance.

We wrote this text with many hands, from conversations and elaborations by women from the territory of the Ribeira River Valley – between Brazil’s South and Southeast regions – who have devoted themselves to fighting against the concession (1) of one of the region’s most important parks, the Alto Ribeira Tourist State Park (PETAR, for its name in Portuguese). The park, located in Iporanga and Apiaí municipalities, is currently administered by the São Paulo state government, and was included in a concessions plan together with other conservation units. This allows private companies (national or international) to gain the right to exploit commercially the part of the territory where the main tourist attractions are concentrated.

The Ribeira River Valley is the region in Brazil that harbors the largest portion of the Atlantic Forest biome, of which 70% is preserved. While in most of the country this biome was destroyed by megaprojects and real estate speculation, in the Ribeira River Valley local communities’ relation with and defense of the forest have contributed to its maintenance. Since last century, the conservation policy conceived to house this biodiversity has been a policy ‘without people’, which created many parks and conservation units that restrict the ways of life of communities (2) in the territory. Only more recently, and through struggle, have some areas gone over to what is termed sustainable use areas. These units are of a type created by Brazil’s National Conservation Units System, and were meant to operate under a regime that tolerates the presence of communities in the territories. This is not entirely the case in practice, seen as even in these locations there are many conflicts between people’s ways of life and the rules of Conservation Units. As a rule, the way environmental and land issues are resolved in the Ribeira River Valley is through the expulsion – forced or by wearing down – of the communities that inhabit it.

Advances in terms of the implementation of more sustainable use areas – where one can practice traditional agriculture, even though permission is required – have allowed communities to remain on the territory. But their real demand has always been the regularization of land ownership. Although they have inhabited the territory for centuries, most communities do not have their lands demarcated or deeds for them, which generates great insecurity. Land conflicts have worsened in Brazil with new policies of digitalization of territorial organization, like the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) (3). In other words, these communities continue to this day fighting for their right to land, as well as fighting in parallel against the environmental policy, especially in the parks.

Privatizing the concession for 30 years: displacements, insecurity and gentrification

This is the case of quilombola and cabocla communities in Iporanga municipality that were superimposed by the Alto Ribeira Tourist State Park (PETAR). Ana Ercilia – a resident of Iporanga since her childhood, environmental monitor and involved in the current struggle against the concession of the park to the private sector – relates that in 1958, at the time when the park was created, people from the territory believed it would be an amusement park, such was the absence of dialogue and transparency of the authorities vis-à-vis the communities. After some time, they came to understand the actual kind of park that had arrived at the territory, already by then owing to restrictions in access to services like electricity, and when people started being prevented from upgrading or enlarging their own homes and yards. Since then, there began a struggle to push back PETAR’s limits to no longer include Bairro da Serra, a district that was ‘cut in half’ when the park was established. Much of its territory ended up inside the park. Bairro da Serra harbors both traditional communities and long-standing residents of Iporanga, as well as important items of Ribeira River Valley’s historical and cultural heritage. The struggle of the dwellers, through their association, ensured an agreement that redrew the park limits so that people’s homes stayed outside the zone with restrictions. However, the farmland remained inside the conservation unit, which greatly restricted people’s way of life and meant that tourism work became families’ only source of income.

The park limits were redrawn but the land ownership regularization of the Bairro da Serra community did not happen. Several families have been displaced by the park to this district, which is in PETAR’s surrounding buffer zone, but the displacement was not accompanied by deeds to the land. The families only have a provisional right to remain, which does not guarantee that the park will not resettle them. (4) This situation is particularly difficult for the women, whose work is concentrated in their own yards and who earn a living mostly from their work there and at various local business initiatives.

Currently, the communities are facing a new offensive onto the territory. The São Paulo state government, based on its privatist policy, has opened an international tender process for the concession of an area of the park – where most of the main tourist attractions are located – for a period of 30 years. This took place in the second half of 2021, already during the pandemic, and without any public consultation whatsoever. Since then, a broad resistance movement against the concession of the park has emerged.

The struggle against the concession is organized with the involvement of residents, peoples and communities, researchers, activists and supporters in general. Women make up a major share of this resistance. Based on their self-organization, they have demonstrated that they are particularly impacted when the government chooses to strengthen public-private partnerships in this way. The question of land regularization, for instance, is being completely ignored in this process. That a private company could literally own the territory for 30 years and that the families, especially the women, should continue to live with the insecurity of not owning their land is an aberration. It clearly demonstrates that the state’s intention in promoting this concession is not improving communities’ quality of life, as it alleges.

Even though the park was imposed upon the communities in the 1950s, over time they appropriated it as best they could. Owing to the intense restrictions placed on their way of life, one of the main sources of income that dwellers have today is community based, autonomously organized work in tourism as environmental monitors. Currently, there are 250 monitors registered with PETAR. Visitors usually hire them, and their presence is compulsory in the case of visits to the caves. They are residents of the communities and beyond presenting the park’s attractions they talk about the history of the Ribeira River Valley and the communities where they live. The organization of monitorship as paid work was part of the negotiations between the state government and the communities as an alternative source of income in the face of restrictions to the use of the territory and to customary practices that were turned into environmental crimes. One of the changes proposed in the privatization RFP specs is that tourists may self-guide inside the park, which would make it even harder for the environmental monitors to obtain an income, as they would cease to be essential to the tourists.

With the concession, communities – and especially women, who run the various small businesses in the area surrounding the park – will cease having a leading role in the tourism field. The concession holder will take on that role. For example, the concession plan involves greatly increasing the number of yearly visits to the park, creating trails for vehicles and publicizing new attractions. The women fighting the concession argue that with these initiatives the government wants to impose another type of tourism on the territory. Instead of people interested in getting to know the communities through the local guides, who are also sources of knowledge about local ways of life, it wants tourism organized by companies that are likely to prioritize the hiring of bilingual guides, for example, rather than members of the local community.

This tourism package undoes the “bread-winning flow”, a kind of economy constructed over time by the communities, which are themselves set to become just another tourist attraction. This new and extremely colonialist tendency has worsened under the neoliberal government of São Paulo state, which is implementing a development program called “Valley of the Future”. Communities other than the ones surrounding PETAR have been classed as tourist attractions by this program, including with signs on highways, without any kind of consultation or dialogue with the communities about this. So the community becomes a foreigner in its own territory. Gentrification, likely to happen via the construction of hotels and higher ticket prices – actions forecast in the concession process –, will make it impossible for community members to access the park, a place they know well and where they enjoy spending time.

The effect forecast is not the valuing of communities and the building of economic alternatives. Rather, people fear they will be pushed out of their territory more and more, and will find themselves forced to migrate to the peripheries of the surrounding cities, a trend already observed particularly among the young, who have not remained in the territory. Furthermore, for the ones that do remain, there is concern about increasing sexual violence and objectification of women’s bodies with the significant inflow of men from the outside. The concession of the park also has no matching measures in terms of improving the public policies that service the community. Given that the concession, if granted, will last 30 years, the women are especially concerned about their young children, who will spend their childhood, adolescence and early adult life in this privatized territory.

This privatization is taking place at the same time as the “Valley of the Future” project advances in the Ribeira River Valley, which also raises doubts as to how the exploitation of the territory will take place. The main front of this development project has so far been opening up the region to mining. (The whole region of Iporanga, including the area of PETAR, was exploited by mining in the past.) Since the concession process provides for the use and exploitation of the territory, this raises the suspicion that mining activities may return in certain parts of the territory, including inside PETAR. After all, as the women state, when it comes to these projects “everything is connected and stitched up in advance”.

In the legal sphere, this whole process has been conducted on the basis of approvals granted in the dead of night, with no participation by communities directly affected. The state government has gone as far as using documents from other meetings (minutes, photos) to claim that consultations with the community about the concession were held. Due to the pandemic, health precautions become the alibi for not holding major public consultations. What has happened in practice is that hearings are deliberately hollowed out since they are proposed in an online format or in-person but in the state capital, in a context where dwellers lack internet access and the resources to travel. According to the specs, the actions to be developed by the company that wins the concession include activities that go against the park’s Management Plan. This unmasks the environmental racism involved in the privatization: if it means companies develop their business, the environmental impact studies need not be taken into account. Nevertheless, this way of conducting the concession, i.e., by disrespecting traditional communities’ right to prior, free and informed consultation (ILO Convention 169), has been understood by part of the Judiciary as valid, which has speeded up the process in spite of these irregularities.

In an even greater offensive than the state government of João Dória, in São Paulo, the federal government of Jair Bolsonaro launched on February 7, 2022, a decree for the concession/privatization of five Conservation Units. One of them, the Serra da Canastra National Park, was created during the military dictatorship and overlaps an area of 1,500 families of rural producers, including 43 communities and 550 traditional families, recognized as Canastreiros.

Women self-organize and resist

When nobody is being heard, least of all are the women. The spaces for participation are scarce and, moreover, tend to be set aside for just a few leaders – men, in general – who, owing to the patriarchal structure of the communities themselves, do not take women’s concerns, perceptions and arguments to the public debate. This, in addition to the disregard the State has shown towards the issue of participation, has made women unite in their own collective, from where they organize the fight against the concession from their self-organization. As well as enhancing the resistance based on a plurality of voices, women’s self-organized spaces have also been important as a form of self-care against the harassment that the State has undertaken over the course of the process, which has even caused mental illness and emotional distress among the communities.

What is evident is that the types of conservation ‘without-people’ that have been adopted as the model and that have for decades dictated the environmental policy of several countries, including Brazil, is very efficient for capital in the current historical period of expansion of its borders. The creation of territories without people means the creation of territories without resistance, where privatizing projects – as in the case of PETAR’s concession – can develop unfettered. We believe that the struggle against the concession in this case will be victorious because the communities of Iporanga have never accepted the fact that their own territory is not their property. Over time, given that the imposition of the park was a reality that could not be changed, they gradually became more and more its owners, appropriating means to live and create within that environment. However, they have always exposed what they see as wrong and fought over the still latent conflicts, like the absence of deeds to their land.

It is not by chance that the State’s concession plan provides for the closing of one of the park’s entrances via Iporanga municipality, even though this entrance greatly facilitates visits to one of the park’s top caves. It is an attempt to exclude the most resistant communities, making it no longer viable for them to access the park or work as environmental monitors. This reminds us that the history of the Ribeira River Valley has been the history of the erasure of the paths trodden by traditional communities, and the construction of paths that privilege the flow of capital. Federal highway BR-116 – a major highway that cuts in half many of the Ribeira River Valley’s municipalities and is responsible for much of the cargo haulage in Southeast Brazil – is an icon of this.

What we know is that the old paths never actually cease to be used, and that the elderly are especially concerned about reminding the young about where these paths pass, where they are and where they end up. The privatization project intends to uproot communities from their territory based on a re-architecture of such paths, but it is failing to take into account the capacity of resistance and inventiveness of the peoples that laid them.

Natália Lobo and Miriam Nobre – Sempreviva Organização Feminista, World March of Women – Brazil.

Jéssica Cristina Pires – Caiçara, quilombola, agroecology technician, representative of communities from Iporanga, PETAR Women’s Collective, Petar Without Concession Movement.

Paula Daniel Fogaça – Biologist; holds a master’s degree in Sustainability.

(1) In order to support the struggle organized by women against the privatization of PETAR and follow this movement, please access https://www.petarsemconcessao.minhasampa.org.br/ and sign the online petition.

(2) The Ribeira River Valley harbors a variety of traditional communities and peoples, like the Guarani Mbyá and Guarani Ñandeva indigenous peoples, and quilombola, caiçara and caboclo communities.

(3) The Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) is a tool created by Brazil’s new forestry code. It is a geo-referenced digital registry of the country’s rural territory. This instrument, which ought to guide the implementation of environmental policies, has been used and a document that justifies what has been termed digital land-grabbing in many countries of the Global South. To find out more, check here.

(4) For more information on the history of Bairro da Serra and relations between Iporanga’s traditional communities and PETAR, see “Florestas e lutas por reconhecimento: território, identidades e direitos na Mata Atlântica brasileira” by Pedro Castelo Branco Silveira. Available here.

Original Source: World Rainforest Movement

Related posts:

Forest Colonialism in Thailand

Forest Colonialism in Thailand

Sexual exploitation and violence against women at the root of the industrial plantation model

Sexual exploitation and violence against women at the root of the industrial plantation model

Africa must unlock the power of its women to save climate change

Africa must unlock the power of its women to save climate change

Campaigners lose court case to stop Ugandan forest clearance

Campaigners lose court case to stop Ugandan forest clearance

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

‘Food and fossil fuel production causing $5bn of environmental damage an hour’

Published

1 month agoon

December 22, 2025

UN GEO report says ending this harm key to global transformation required ‘before collapse becomes inevitable’.

Related posts:

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

New billion-dollar loans to fossil fuel companies from SEB, Nordea and Danske Bank.

New billion-dollar loans to fossil fuel companies from SEB, Nordea and Danske Bank.

Fossil fuel opponents lobby Africans for support

Fossil fuel opponents lobby Africans for support

Ecological land grab: food vs fuel vs forests

Ecological land grab: food vs fuel vs forests

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Britain, Netherlands withdraw $2.2 billion backing for Total-led Mozambique LNG

Published

2 months agoon

December 17, 2025

CONSTRUCTION HALTED IN 2021, BUT DUE TO RESTART

PROJECT CAN PROCEED WITHOUT UK, DUTCH FINANCING, TOTAL HAS SAID

CRITICISM FROM ENVIRONMENTAL, HUMAN RIGHTS GROUPS

Related posts:

Uganda, Total sign crude oil pipeline deal

Uganda, Total sign crude oil pipeline deal

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

NGOs file suit against Total over Uganda oil project

NGOs file suit against Total over Uganda oil project

Agribusiness Company with financial support from UK, US and Netherlands is dispossessing thousands.

Agribusiness Company with financial support from UK, US and Netherlands is dispossessing thousands.

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

The secretive cabal of US polluters that is rewriting the EU’s human rights and climate law

Published

2 months agoon

December 5, 2025

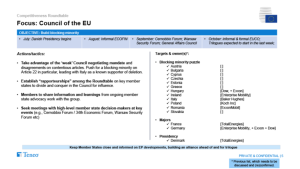

Leaked documents reveal how a secretive alliance of eleven large multinational enterprises has worked to tear down the EU’s flagship human rights and climate law, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). The mostly US-based coalition, which calls itself the Competitiveness Roundtable, has targeted all EU institutions, governments in Europe’s capitals, as well as the Trump administration and other non-EU governments to serve its own interests. With European lawmakers soon moving ahead to completely dilute the CSDDD at the expense of human rights and the climate, this research exposes the fragility of Europe’s democracy.

Key findings

- Leaked documents reveal how a secretive alliance of eleven companies, including Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Koch, Inc., has worked under the guise of a “Competitiveness Roundtable” to get the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) either scrapped or massively diluted.

- The companies, most of which are headquartered in the US and operate in the fossil fuel sector, aimed to “divide and conquer in the Council”, sideline “stubborn” European Commission departments, and push the European People’s Party (EPP) in the European Parliament “to side with the right-wing parties as much as possible”.

- Chevron and ExxonMobil were in charge of mobilising pressure against the CSDDD from non-EU countries. The Roundtable companies endeavoured to get the CSDDD high on the agenda of the US-EU trade negotiations and also worked on mobilising other countries against the CSDDD, in order to disguise the US influence.

- Roundtable companies paid the TEHA Group – a think tank – to write a research report and organise an event on EU competitiveness, which echoed the Roundtable’s position and cast doubt on the European Commission’s assessment of the economic impact of the CSDDD.

While Europeans were told that their governments were negotiating a landmark law to hold corporations accountable for human rights abuses and climate damage, a secretive alliance of US fossil fuel giants was working behind the scenes to destroy it. Collaborating under the innocent-sounding name ‘Competitiveness Roundtable’, eleven multinational enterprises have worked closely to eviscerate several EU sustainability laws, including the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). This Competitiveness Roundtable may be unknown, but its members are a who’s-who of polluting, mainly US, multinationals, including Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Dow. The group seems to have run rings around all branches of the EU and the Trump administration to get what they want: scrapping, or at least hugely diluting, the CSDDD.

Leaked documents obtained by SOMO reveal how, under the pretext of the now-near-magical concept of ‘competitiveness’, these companies plotted to hijack democratically adopted EU laws and strip them of all meaningful provisions, including those on climate transition plans, civil liability, and the scope of supply chains. EU officials appear not to have known who they were up against. But the documents obtained by SOMO show a high level of organisation and strategising with a clear facilitator: Teneo, a US public relations and consultancy company.

The documents indicate that many of the companies involved wanted to stay hidden from view. After all, if it were widely known that a secretive group of mostly American fossil fuel companies like Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Koch, Inc. was working as a coordinated organisation to dilute an EU climate and human rights law, that might raise questions and serious concern among the public and the policymakers they were targeting. Many of the companies in the Roundtable have never publicly spoken out against the CSDDD.

Big Oil’s ‘Competitiveness Roundtable’

The Competitiveness Roundtable is dominated by fossil fuel companies, including three Big Oil companies (ExxonMobil, Chevron, TotalEnergies) and three other companies with activities in the oil and gas sector (Koch, Inc., Honeywell, and Baker Hughes). Other members are Nyrstar (minerals and metals, a subsidiary of Trafigura Group); Dow, Inc. (chemicals); Enterprise Mobility (car rentals); and JPMorgan Chase (finance).

Teneo, the Roundtable’s coordinator, has a track record(opens in new window) of working with fossil fuel companies, including Chevron, Shell, and Trafigura, and was hired by the government of Azerbaijan to handle public relations(opens in new window) when it hosted the COP29 climate conference.

In February 2025, the European Commission published the Omnibus I proposal(opens in new window), which aims to “simplify” several EU sustainability laws, including the CSDDD. The documents obtained by SOMO reveal that the Roundtable companies, which have been meeting weekly since at least March 2025, worked on deep interventions within each of the three EU institutions to get the Omnibus I package to align exactly with their views. The EU institutions are expected to reach a final agreement on Omnibus I by the end of 2025.

The documents reveal that the Roundtable companies’ activities in the Parliament are far more significant than what is visible in the EU Transparency Register(opens in new window). Eight of the Roundtable’s lobbying meetings during the Strasbourg plenary sessions of May and June 2025, listed in the Transparency Register, show Teneo as the only attendee, thereby failing to disclose the names of other Roundtable companies that participated in these meetings. Another three meetings the Roundtable held were not found in the EU Transparency Register(opens in new window) at all.

“Divide and conquer” the Council

In the European Council, the Roundtable plotted to “divide and conquer” EU governments to get the climate article in the CSDDD deleted. In June 2025, during the final weeks of negotiations in the Council on the Omnibus I proposal, the Roundtable discussed lobbying EU government leaders to “intervene politically” to ensure its priorities were included in the Council’s negotiation mandate. Subsequently, German Chancellor Merz and French President Macron reportedly(opens in new window) personally intervened(opens in new window) in the Council’s political process, leading to a dramatic dilution(opens in new window) of the texts(opens in new window) negotiated in the months before the intervention. Several of the changes made to the texts strongly align with the Roundtable’s demands, including delaying and substantially weakening the climate obligations, scrapping EU civil liability provisions, and limiting the responsibility of companies to take responsibility for their supply chains (the ‘Tier 1’ restriction).

Competitiveness Roundtable meeting document, 11 July 2025.

Additionally, the documents reveal that the Roundtable is still aiming to drum up a “blocking minority” to overturn the Council’s negotiation mandate during the trilogue negotiations, which started in November 2025. By “tak[ing] advantage of the ‘weak’ Council negotiating mandate” and disagreements between EU Member States on “contentious articles”, the Competitiveness Roundtable companies hope to force the Danish Council presidency to give up on including any form of climate obligations in the CSDDD – despite EU Member States’ agreement on this in the June 2025 Council mandate(opens in new window) .

To implement the divide-and-conquer strategy, the Roundtable assigned specific companies to “establish rapporteurships” with different EU governments. TotalEnergies would target the French, Belgian, and Danish governments, and ExxonMobil would target Germany, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Romania.

Circumventing “stubborn” European Commission departments

The Roundtable also discussed working on “circumvent[ing]” two “stubborn” European Commission departments involved in the Omnibus political process, DG JUST and DG FISMA, which, in their view, were “unlikely to be willing to see our side of the story”. According to the documents, DG JUST opposed deleting the climate article and restricting the Directive’s scope to only very large enterprises. The Roundtable aimed to diminish the role of these departments by pressuring President Von der Leyen and Commissioners McGrath (DG JUST) and Albuquerque (DG FISMA) by “organising letters from Irish and German business groups” and using an event held by the European Roundtable for Industry to “target” Von der Leyen and McGrath.

Read full report: Somo.nl

Source: Somo

Related posts:

Victims of human rights violations in Uganda still waiting for redress

Victims of human rights violations in Uganda still waiting for redress

UN Human Rights Chief urges EU leaders to approve key business and human rights legislation

UN Human Rights Chief urges EU leaders to approve key business and human rights legislation

Business, UN, Govt & Civil Society urge EU to protect sustainability due diligence framework

Business, UN, Govt & Civil Society urge EU to protect sustainability due diligence framework

Development financiers fuel human rights abuses – New Report

Development financiers fuel human rights abuses – New Report

Indigenous communities in Eastern Nepal accuse the World Bank’s Linked Cable Car Project of rights violations.

Why govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

Evicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Swedish pension fund drops TotalEnergies amid rising EACOP risks

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoWomen environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoUganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

-

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago

FARM NEWS2 weeks ago200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoEvicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days agoWitness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days agoWhy govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 hours ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 hours agoIndigenous communities in Eastern Nepal accuse the World Bank’s Linked Cable Car Project of rights violations.