NGO WORK

Development banks have no business financing agribusiness

Published

4 years agoon

On the eve of an annual gathering of public development banks in Rome, 280 groups from 70 countries have signed a letter slamming them for bankrolling the expansion of industrial agriculture, environmental destruction and corporate control of the food system. The signatories affirm only fully public and accountable funding mechanisms based on people’s actual needs can achieve real solutions to the global food crisis.

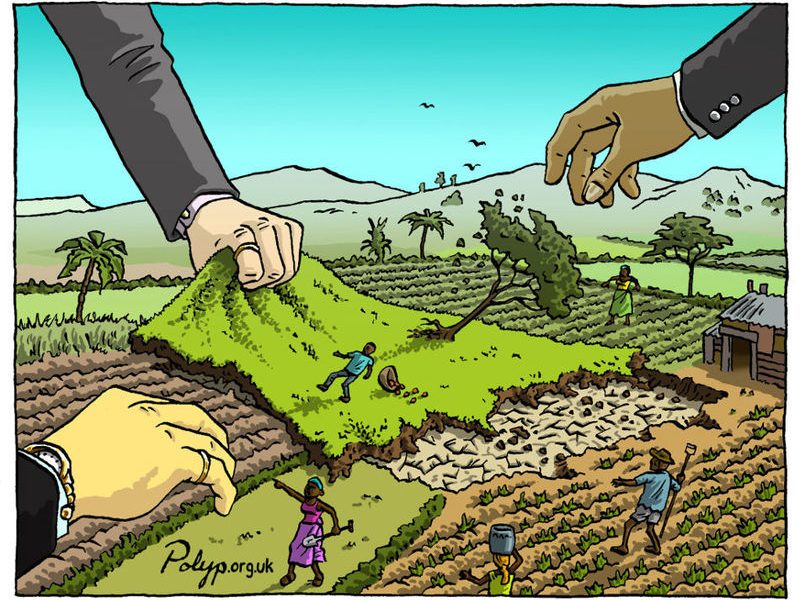

Over 450 Public Development Banks (PDBs) from around the world are gathering in Rome from 19 to 20 October 2021 for a second international summit, dubbed Finance in Common. During the first summit in Paris in 2020, over 80 civil-society organizations published a joint statement demanding that the PDBs stop funding agribusiness companies and projects that take land and natural resources away from local communities. This year, however, PDBs have made agriculture and agribusiness the priority of their second summit. This is of serious concern for the undersigned groups as PDBs have a long track-record of making investments in agriculture that benefit private interests and agribusiness corporations at the expense of farmers, herders, fishers, food workers and Indigenous Peoples, undermining their food sovereignty, ecosystems and human rights.

Our concerns

PDBs are public institutions established by national governments or multilateral agencies to finance government programs and private companies whose activities are said to contribute to the improvement of people’s lives in the places where they operate, particularly in the Global South. Many multilateral development banks, a significant sub-group of PDBs, also provide technical and policy advice to governments to change their laws and policies to attract foreign investment.

As public institutions, PDBs are bound to respect, protect and fulfil human rights and are supposed to be accountable to the public for their actions. Today, development banks collectively spend over US$2 trillion a year financing public and private companies to build roads, power plants, factory farms, agribusiness plantations and more in the name of “development” – an estimated US$1.4 trillion goes into the sole agriculture and food sector. Their financing of private companies, whether through debt or the purchase of shares, is supposed to be done for a profit, but much of their spending is backed and financed by the public – by people’s labor and taxes.

The number of PDBs and the funding they receive is growing.The reach of these banks is also growing as they are increasingly channeling public funds through private equity, “green finance” and other financial schemes to deliver the intended solutions instead of more traditional support to government programs or non-profit projects. Money from a development bank provides a sort of guarantee for companies expanding into so-called high-risk countries or industries. These guarantees enable companies to raise more funds from private lenders or other development banks, often at favorable rates. Development banks thus play a critical role in enabling multinational corporations to expand further into markets and territories around the world – from gold mines in Armenia, to controversial hydroelectric dams in Colombia, to disastrous natural gas projects in Mozambique – in ways they could not do otherwise.

Additionally, many multilateral development banks work to explicitly shape national level law and policy through their technical advice to governments and ranking systems such as the Enabling the Business of Agriculture of the World Bank. The policies they support in key sectors — including health, water, education, energy, food security and agriculture — tend to advance the role of big corporations and elites. And when affected local communities, including Indigenous Peoples and small farmers protest, they are often not heard or face reprisals. For example, in India, the World Bank advised the government to deregulate the agricultural marketing system, and when the government implemented this advice without consulting with farmers and their organisations, it led to massive protests.

Public Development Banks claim that they only invest in “sustainable” and “responsible” companies and that their involvement improves corporate behavior. But these banks have a heavy legacy of investing in companies involved in land grabbing, corruption, violence, environmental destruction and other severe human rights violations, from which they have escaped any meaningful accountability. The increasing reliance of development banks on offshore private equity funds and complex investment webs, including so called financial intermediaries, to channel their investments makes accountability even more evasive and enables a small and powerful financial elite to capture the benefits.

It is alarming that Public Development Banks are now taking on more of a coordinated and central role when it comes to food and agriculture. They are a part of the global financial architecture that is driving dispossession and ecological destruction, much of which is caused by agribusiness. Over the years, their investment in agriculture has almost exclusively gone to companies engaged in monoculture plantations, contract growing schemes, animal factory farms, sales of hybrid and genetically modified seeds and pesticides, and digital agriculture platforms dominated by Big Tech. They have shown zero interest in or capacity to invest in the farm, fisher and forest communities that currently produce the majority of the world’s food. Instead, they are bankrolling land grabbers and corporate agribusinesses and destroying local food systems.

Painful examples

Important examples of the pattern we see Public Development Banks engaging in:

-

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the European Investment Bank have provided generous financing to the agribusiness companies of some of Ukraine’s richest oligarchs, who control hundreds of thousands of hectares of land.

-

SOCFIN of Luxembourg and SIAT of Belgium, the two largest oil palm and rubber plantation owners in Africa, have received numerous financial loans from development banks, despite their subsidiaries being mired in land grabbing, corruption scandals and human rights violations.

-

Multiple development banks (including Swedfund, BIO, FMO and the DEG) financed the failed sugarcane plantation of Addax Bioenergy in Sierra Leone that has left a trail of devastation for local communities after the company’s exit.

-

The UK’s CDC Group and other European development banks (including BIO, DEG, FMO and Proparco) poured over $150 million into the now bankrupt Feronia Inc’s oil palm plantations in the DR Congo, despite long-standing conflicts with local communities over land and working conditions, allegations of corruption and serious human rights violations against villagers.

-

The United Nations’ Common Fund for Commodities invested in Agilis Partners, a US-owned company, which is involved in the violent eviction of thousands of villagers in Uganda for a large-scale grain farm.

-

Norfund and Finnfund own Green Resources, a Norwegian forestry company planting pine trees in Uganda on land taken from thousands of local farmers, with devastating effects on their livelihoods.

-

The Japan Bank for International Cooperation and the African Development Bank invested in a railway and port infrastructure project to enable Mitsui of Japan and Vale of Brazil to export coal from their mining operations in northern Mozambique. The project, connected to the controversial ProSavana agribusiness project, has led to land grabbing, forced relocations, fatal accidents and the detention and torture of project opponents.

-

The China Development Bank financed the ecologically and socially disastrous Gibe III dam in Ethiopia. Designed for electricity generation and to irrigate large-scale sugar, cotton and palm oil plantations such as the gargantuan Kuraz Sugar Development Project, it has cut off the river flow that the indigenous people of the Lower Omo Valley relied on for flood retreat agriculture.

-

In Nicaragua, FMO and Finnfund financed MLR Forestal, a company managing cocoa and teak plantations, which is controlled by gold mining interests responsible for displacement of Afro-descendant and Indigenous communities and environmental degradation.

-

The International Finance Corporation and the Inter-American Development Bank Invest have recently approved loans to Pronaca, Ecuador’s 4th largest corporation, to expand intensive pig and poultry production despite opposition from international and Ecuadorian groups, including local indigenous communities whose water and lands have been polluted by the company’s expansive operations.

-

The Inter-American Development Bank Invest is considering a new $43 million loan for Marfrig Global Foods, the world’s 2nd largest beef company, under the guise of promoting “sustainable beef.” Numerous reports have found Marfrig’s supply chain directly linked to illegal deforestation in the Amazon and Cerrado and human rights violations. The company has also faced corruption charges. A global campaign is now calling for PDBs to immediately divest from all industrial livestock operations.

We need better mechanisms to build food sovereignty

Governments and multilateral agencies are finally beginning to acknowledge that today’s global food system has failed to address hunger and is a key driver of multiple crises, from pandemics to biodiversity collapse to the climate emergency. But they are doing nothing to challenge the corporations who dominate the industrial food system and its model of production, trade and consumption. To the contrary, they are pushing for more corporate investment, more public private partnerships and more handouts to agribusiness.

This year’s summit of the development banks was deliberately chosen to follow on the heels of the UN Food Systems Summit. It was advertised as a global forum to find solutions to problems afflicting the global food system but was hijacked by corporate interests and became little more than a space for corporate greenwashing and showcasing industrial agriculture. The event was protested and boycotted by social movements and civil society, including through the Global People´s Summit and the Autonomous People´s response to the UN Food Systems Summit, as well as by academics from across the world.

The Finance in Common summit, with its focus on agriculture and agribusiness, will follow the same script. Financiers overseeing our public funds and mandates will gather with elites and corporate representatives to strategize on how to keep the money flowing into a model of food and agriculture that is leading to climate breakdown, increasing poverty and exacerbating all forms of malnutrition. Few if any representatives from the communities affected by the investments of the development banks, people who are on the frontlines trying to produce food for their communities, will be invited in or listened to. PDBs are not interested. They seek to fund agribusinesses, which produce commodities for trade and financial schemes for profits rather than food for nutrition.

Last year, a large coalition of civil-society organizations made a huge effort just to get the development banks to agree to commit to a human rights approach and community-led development. The result was only some limited language in the final declaration, which has not been translated into action.

We do not want any more of our public money, public mandates and public resources to be wasted on agribusiness companies that take land, natural resources and livelihoods away from local communities. Therefore:

We call for an immediate end to the financing of corporate agribusiness operations and speculative investments by public development banks.

We call for the creation of fully public and accountable funding mechanisms that support peoples’ efforts to build food sovereignty, realize the human right to food, protect and restore ecosystems, and address the climate emergency.

We call for the implementation of strong and effective mechanisms that provide communities with access to justice in case of adverse human rights impacts or social and environmental damages caused by PDB investments.

Fundación Plurales – Argentina

Fundación Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (FARN) – Argentina

Foro Ambiental Santiagueño – Argentina

Armenian Women For Health &Healthy Environment NGO /AWHHE/ – Armenia

Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance – Australia

SunGem – Australia

Welthaus Diözese Graz-Seckau – Austria

Turkmen Initiative for Human Rights – Austria

FIAN Austria – Austria

Oil Workers’ Rights Protection Organization Public Union – Azerbaijan

Initiative for Right View – Bangladesh

Right to Food South Asia – Bangladesh

IRV – Bangladesh

Bangladesh Agricultural Farm Labour Federation [BAFLF] – Bangladesh

NGO “Ecohome” – Belarus

Eclosio – Belgium

AEFJN – Belgium

FIAN Belgium – Belgium

Entraide et Fraternité – Belgium

Africa Europe Faith & Justice Network (AEFJN) – Belgium

Coalition for Fair Fisheries Arrangements – Belgium

Eurodad – Belgium

Friends of the Earth Europe – Belgium

Alianza Animalista La Paz – Bolivia

Instituto de Estudos Socioeconômicos (Inesc) – Brazil

Centro Ecologico – Brazil

FAOR Fórum da Amazônia Oriental – Brazil

Articulação Agro é Fogo – Brazil

Campanha Nacional de Combate e Prevenção ao Trabalho Escravo – Comissão Pastoral da Terra/CPT – Brazil

Clínica de Direitos Humanos da Amazônia -PPGD/UFPA – Brazil

Universidade Federal Fluminense IPsi – Brazil

Associação Brasileira de Reforma Agrária – Brazil

Rede Jubileu Sul Brasil – Brazil

Alternativas para pequena agricultura no Tocantins APATO – Brazil

CAPINA Cooperação e Apoio a Projetos de Inspiração Alternativa – Brazil

Marcha Mundial por Justiça Climática / Marcha Mundial do Clima – Brazil

MNCCD – Movimento Nacional Contra Corrupção e pela Democracia – Brazil

Marcha Mundial por Justiça Climática/Marcha Mundial do Clima – Brazil

Support Group for Indigenous Youth – Brazil

Comissão Pastoral da Terra -CPT – Brazil

Equitable Cambodia – Cambodia

Coalition of Cambodian Farmers Community – Cambodia

Struggle to Economize Future Environment (SEFE) – Cameroon

Synaparcam – Cameroon

APDDH -ASSISTANCE – Cameroon

Inter Pares – Canada

Vigilance OGM – Canada

National Farmers Union – Canada

SeedChange – Canada

Place de la Dignité – Canada

Corporación para la Protección y Desarrollo de Territorios Rurales- PRODETER – Colombia

Grupo Semillas – Colombia

Groupe de Recherche et de Plaidoyer sur les Industries Extractives (GRPIE) – Côte d’Ivoire

Réseau des Femmes Braves (REFEB) – Côte d’Ivoire

CLDA – Côte d’Ivoire

Counter Balance – Czech Republic

AfrosRD – Dominican Republic

Conseil Régional des Organisations Non gouvernementales de Développement – DR Congo

Construisons Ensemble le MONDE – DR Congo

Synergie Agir Contre la Faim et le Réchauffement Climatique , SACFRC. – DR Congo

COPACO-PRP – DR Congo

AICED – DR Congo

Réseaux d’informations et d’appui aux ONG en République Démocratique du Congo ( RIAO – RDC) – DR Congo

Latinoamérica Sustentable – Ecuador

Housing and Land Rights Network – Habitat International Coalition – Egypt

Pacific Islands Association of Non-Governmental Organisations (PIANGO) – Fiji

Internationale Situationniste – France

Pouvoir d’Agir – France

Europe solidaire sans frontières (ESSF) – France

Amis de la Terre France – France

Médias Sociaux pour un Autre Monde – France

ReAct Transnational – France

CCFD-Terre Solidaire – France

CADTM France – France

Coordination SUD – France

Движение Зеленных Грузии – Georgia

NGO “GAMARJOBA” – Georgia

StrongGogo – Georgia

FIAN Deutschland – Germany

Rettet den Regenwald – Germany

Angela Jost Translations – Germany

urgewald e.V. – Germany

Abibinsroma Foundation – Ghana

Alliance for Empowering Rural Communities – Ghana

Organización de Mujeres Tierra Viva – Guatemala

Campaña Guatemala sin hambre – Guatemala

PAPDA – Haïti

Centre de Recherche et d’Action pour le Developpement (CRAD) – Haiti

Ambiente, Desarrollo y Capacitación (ADC ) – Honduras

Rashtriya Raithu Seva Samithi – India

All India Union of Forest Working People AIUFWP – India

Centre for Financial Accountability – India

People First – India

Environics Trust – India

ToxicsWatch Alliance – India

Food Sovereignty Alliance – India

Indonesia for Global Justice (IGJ) – Indonesia

kruha – Indonesia

Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia (WALHI) – Indonesia

JPIC Kalimantan – Indonesia

تانيا جمعه /منظمه شؤون المراه والطفل – Iraq

ICW-CIF – Italy

PEAH – Policies for Equitable Access to Health – Italy

Focsiv Italian federation christian NGOs – Italy

Schola Campesina APS – Italy

Casa Congo- Italy

ReCommon – Italy

Japan International Volunteer Center (JVC) – Japan

Team OKADA – Japan

taneomamorukai – Japan

VoiceForAnimalsJapan – Japan

Keisen University – Japan

000 PAF NPO – Japan

Missionary Society of Saint Columban, Japan – Japan

Migrants around 60 – Japan

Mura-Machi Net (Network between Villages and Towns) – Japan

Japan Family Farmers Movement (Nouminren) – Japan

Pacific Asia Resorce Center(PARC) – Japan

A Quater Acre Farm-Jinendo – Japan

Friends of the Earth Japan – Japan

Alternative People’s Linkage in Asia (APLA) – Japan

Mekong Watch – Japan

Family Farming Platform Japan – Japan

Africa Japan Forum – Japan

ATTAC Kansai – Japan

ATTAC Japan – Japan

Association of Western Japan Agroecology (AWJA) – Japan

Mennovillage Naganuma – Japan

Phenix Center – Jordan

Mazingira Institute – Kenya

Dan Owala – Kenya

Jamaa Resource Initiatives – Kenya

Kenya Debt Abolition Network – Kenya

Haki Nawiri Afrika – Kenya

Euphrates Institute-Liberia – Liberia

Green Advocates International (Liberia) – Liberia

Sustainable Development Institute (SDI) – Liberia

Alliance for Rural Democracy (ARD) – Liberia

Frères des Hommes – Luxembourg

SOS FAIM – Luxembourg

Collectif pour la défense des terres malgaches – TANY – Madagascar

Third World Network – Malaysia

Appui Solidaire pour le Développement de l’Aide au Développement – Mali

Réseau CADTM Afrique – Mali

Lalo – Mexico

Tosepanpajt A.C – Mexico

Maya sin Fronteras – Mexico

Centro de Educación en Apoyo a la Producción y al Medio Ambiente, A.C. – Mexico

Mujeres Libres COLEM AC – México

Grupo de Mujeres de San Cristóbal Las Casas AC – México

Colectivo Educación para la Paaz y los Derechos Humanos A.C. (CEPAZDH) – México

Red Nacional de Promotoras Rurales – México

Dinamismo Juvenil A.C – México

Cultura Ambiental en Expansión AC – México

Observatorio Universitario de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional del Estado de Guanajuato – México

Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación y Desarrollo Alternativo U Yich Lu’um AC – México

The Hunger Project México – México

Americas Program/Americas.Org – México

Association Talassemtane pour l’Environnement et Développement (ATED) – Morocco

Espace de Solidarité et de Coopération de l’Oriental – Morocco

LVC Maroc – Morocco

EJNA – Morocco

NAFSN – Morocco

Fédération nationale du secteur agricole – Morocco

Association jeunes pour jeunes – Morocco

Plataforma Mocambicana da Mulher e Rapariga Cooperativistas/AMPCM – MOZAMBIQUE – Mozambique

Justica Ambiental – JA! – Mozambique

Community Empowerment and Social Justice Network (CEMSOJ) – Nepal

WILPF NL – Netherlands

Milieudefensie – Netherlands

Platform Aarde Boer Consument – Netherlands

Both ENDS – Netherlands

Foundation for the Conservation of the Earth,FOCONE – Nigeria

Lekeh Development Foundation (LEDEF) – Nigeria

Nigeria Coal Network – Nigeria

Spire – Norway

Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum – Pakistan

Gaza Urban Agriculture Platform (GUPAP) – Palestine

Union of Agricultural Work Committees – Palestine

WomanHealth Philippines – Philippines

Agroecology X – Philippines

SEARICE – Philippines

Alter Trade Foundation for Food Sovereignty, Inc – Philippines

Association pour la défense des droits à l’eau et à l’assainissement – Sénégal

Biotech Services Sénégal – Sénégal

Association Sénégalaise des Amis de la Nature – Sénégal

Alliance Sénégalaise Contre la Faim et la Malnutrition – Sénégal

Association Sénégalaise des Amis de la Nature – Sénégal

Alliance Sénégalaise Contre la Faim et la Malnutrition – Sénégal

Green Scenery – Sierra Leone

Land for Life – Sierra Leone

JendaGbeni Centre for Social Change Communications – Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone Land Alliance – Sierra Leone

African Centre for Biodiversity – South Africa

African Children Empowerment – South Africa

Cooperative and Policy Alternative Centre – South Africa

Fish Hoek Valley Ratepayers and Residents Association – South Africa

Consciously Organic – South Africa

Wana Johnson Learning Centre – South Africa

Aha Properties – South Africa

Sacred Earth & Storm School – South Africa

Earth Magic – South Africa

Oasis – South Africa

Envirosense – South Africa

Greenstuff – South Africa

WoMin African Alliance – South Africa

Seonae Eco Centre – South Africa

Eco Hope – South Africa

Kos en Fynbos – South Africa

Ghostwriter Grant – South Africa

Mariann Coordinating Committee – South Africa

Khanyisa Education and Development Trust – South Africa

LAMOSA – South Africa

Ferndale Food Forest and Worm Farm – South Africa

Mxumbu Youth Agricultural Coop – South Africa

PHA Food & Farming Campaign – South Africa

SOLdePAZ.Pachakuti – Spain

Amigos de la Tierra – Spain

Sindicato Andaluz de Trabajadores/AS – Spain

Salva la Selva – Spain

Loco Matrifoco – Spain

National Fisheries Solidarity(NAFSO) – Sri Lanka

Movement for Land and Agricultural Reform (MONLAR) – Sri Lanka

Agr. Graduates Cooperatives Union – Sudan

FIAN Sweden – Sweden

FIAN Suisse – Switzerland

Bread for all – Switzerland

Foundation for Environmental Management and Campaign Against Poverty – Tanzania

World Animal Protection – Thailand

Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact – Thailand

PERMATIL – Timor-Leste

Afrique Eco 2100 – Togo

AJECC – Togo

ATGF – Tunisia

Forum Tunisien des Droits Economiques et Sociaux – Tunisia

Agora Association – Turkey

Uganda Land Rights Defenders – Uganda

Hopes for youth development Association – Uganda

Uganda Consortium on Corporate Accountability – Uganda

Centre for Citizens Conserving Environment &Management (CECIC) – Uganda

Buliisa Initiative for Rural Development Organisation (BIRUDO)) – Uganda

Twerwaneho Listeners Club – Uganda

Alliance for Food Soverignity in Africa – Uganda

Global Justice Now – UK

Friends of the Earth International – UK

Compassion in World Farming – UK

Environmental Justice Foundation – UK

Fresh Eyes – UK

War on Want – UK

Friends of the Earth US – US

A Growing Culture – US

Center for Political Innovation – US

GMO/Toxin Free USA – US

Friends of the Earth US – US

Thousand Currents – US

Local Futures – US

National Family Farm Coalition – US

Community Alliance for Global Justice/AGRA Watch – US

Bank Information Center – US

Seeding Sovereignty – US

Yemeni Observatory for Human Rights – Yemen

Zambia Alliance for Agroecology and Biodiversity – Zambia

Zambian Governance Foundation for Civil Society – Zambia

Urban Farming Zimbabwe – Zimbabwe

Centre for Alternative Development – Zimbabwe

FACHIG Trust – Zimbabwe

Red Latinoamericana por Justicia Económica y Social – Latindadd – América Latina

European Coordination Via Campesina – Europe

Arab Watch Coalition – Middle East and North Africa

FIAN International – International

International Alliance of Inhabitants – International

Society for International Development – International

ActionAid International – International

International Accountability Project – International

Habitat International Coalition – General Secretariat – International

CIDSE – International

ESCR-Net – International

World Rainforest Movement – International

Transnational Institute – International

GRAIN – International

Original Source: grian.org

Related posts:

DR Congo oil palm company bankrolled by development banks unleashes wave of violence against villagers after peaceful protests

DR Congo oil palm company bankrolled by development banks unleashes wave of violence against villagers after peaceful protests

They should not be called public development banks

They should not be called public development banks

Open letter to African Development Bank and Nordic Development Fund: Address reprisals against Paten Clan

Open letter to African Development Bank and Nordic Development Fund: Address reprisals against Paten Clan

CSOs urge banks and other IFIs not to finance E.Africa oil pipeline project…

CSOs urge banks and other IFIs not to finance E.Africa oil pipeline project…

You may like

NGO WORK

Violations against Kenya’s indigenous Ogiek condemned yet again by African Court

Published

3 weeks agoon

January 13, 2026

Minority Rights Group welcomes today’s decision by the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights in the case of Ogiek people v. Government of Kenya. The decision reiterates previous findings of more than a decade of unremedied violations against the indigenous Ogiek people, centred on forced evictions from their ancestral lands in the Mau forest.

The Court showed clear impatience concerning Kenya’s failure to implement two landmark rulings in favour of the indigenous Ogiek people: in a 2017 judgment, that their human rights had been violated by Kenya’s denial of access to their land, and in a 2022 judgment, which ordered Kenya to pay nearly 160 million Kenyan shillings (about 1.3 million USD) in compensation and to restitute their ancestral lands, enabling them to enjoy the human rights that have been denied them.

Despite tireless activism from the community and the historic nature of both judgments, Kenya has not implemented any part of either decision. The community remains socioeconomically marginalized as a result of their eviction and dispossession. Evictions have continued, notably in 2023 with 700 community members made homeless and their property destroyed, and in 2020 evicting about 600, destroying their homes in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Daniel Kobei, Executive Director of the Ogiek Peoples’ Development Program stated, ‘We have been at the African Court six times to fight for our rights to live on our lands as an indigenous people – rights which our government has denied us and continues to violate, compounding our plights and marginalization, despite clear orders from the African Court for our government to remedy the violations. This is the seventh time, and we were hopeful that the Court would be more strict to the government of Kenya in ensuring that a workable roadmap be followed in implementation of the two judgments.’

Kenya has repeatedly justified the eviction of Ogiek as necessary for conservation, although the forest has seen significant harm since evictions began. Many in the community see a connection between their eviction and Kenya’s participation in lucrative carbon credit schemes.

‘The Court’s decision underscores the importance of timely and full implementation of measures imposed on a state which has been found to be in breach of their internationally agreed obligations. Kenya must now repay its debt to the indigenous Ogiek by restituting their land and making reparations, among other remedies ordered by the Court’, said Samuel Ade Ndasi, African Union Advocacy and Litigation Officer at Minority Rights Group.

The decision states, ‘the court orders the respondent state to immediately take all necessary steps, be they legislative or administrative or otherwise, to remedy all the violations established in the judgment on merits.’ The court also reaffirmed that no state can invoke domestic laws to justifiy a breach of international obligations.

Both of the original judgments were historic precedents, breaking new ground on the issue of restitution and compensation for collective violations experienced by indigenous peoples and confirming the vital role of indigenous peoples in safeguarding ecosystems, that states must respect and protect their land rights, that lands appropriated from them in the name of conservation without free, prior and informed consent must be returned, and their right to be the ultimate decision makers about what happens on their lands. Today’s decision adds to this tally of precedents as it is the first decision of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights concerning the record of a state in implementing a binding decision.

The case

In October 2009, the Kenyan government, through the Kenya Forestry Service, issued a 30-day eviction notice to the Ogiek and other settlers of the Mau Forest, demanding that they leave the forest. Concerned that this was a perpetuation of the historical land injustices already suffered, and having failed to resolve these injustices through repeated national litigation and advocacy efforts, the Ogiek decided to lodge a case against their government before the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights with the assistance of Minority Rights Group, the Ogiek Peoples’ Development Program and the Centre for Minority Rights Development. The African Commission issued interim measures, which were flouted by the Government of Kenya and thereafter referred the case to the African Court based on the complementarity relationship between the African Commission and the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights and on the grounds that there was evidence of serious or massive human rights violations.

On 26 May 2017, after years of litigation, a failed attempt at amicable settlement and an oral hearing on the merits, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights rendered a merits judgment in favour of the Ogiek people. It held that the government had violated the Ogiek’s rights to communal ownership of their ancestral lands, to culture, development and use of natural resources, as well as to be free from discrimination and practise their religion or belief. On 23 June 2022, the Court rejected Kenya’s objections and set out the reparations owed for the violations established in the 2017 judgment.

Source: minorityrights.org

Related posts:

Trauma and Land Loss: New Study Focuses on Mental Health of Evicted Indigenous People

Trauma and Land Loss: New Study Focuses on Mental Health of Evicted Indigenous People

Justice Denied: East African Court of Justice Grants Tanzanian Government Impunity to Trample Human Rights of the Maasai

Justice Denied: East African Court of Justice Grants Tanzanian Government Impunity to Trample Human Rights of the Maasai

EACOP: East African Court of Justice will hear arguments on court’s jurisdiction

EACOP: East African Court of Justice will hear arguments on court’s jurisdiction

Tanzanian High Court Tramples Rights of Indigenous Maasai Pastoralists to Boost Tourism Revenues

Tanzanian High Court Tramples Rights of Indigenous Maasai Pastoralists to Boost Tourism Revenues

NGO WORK

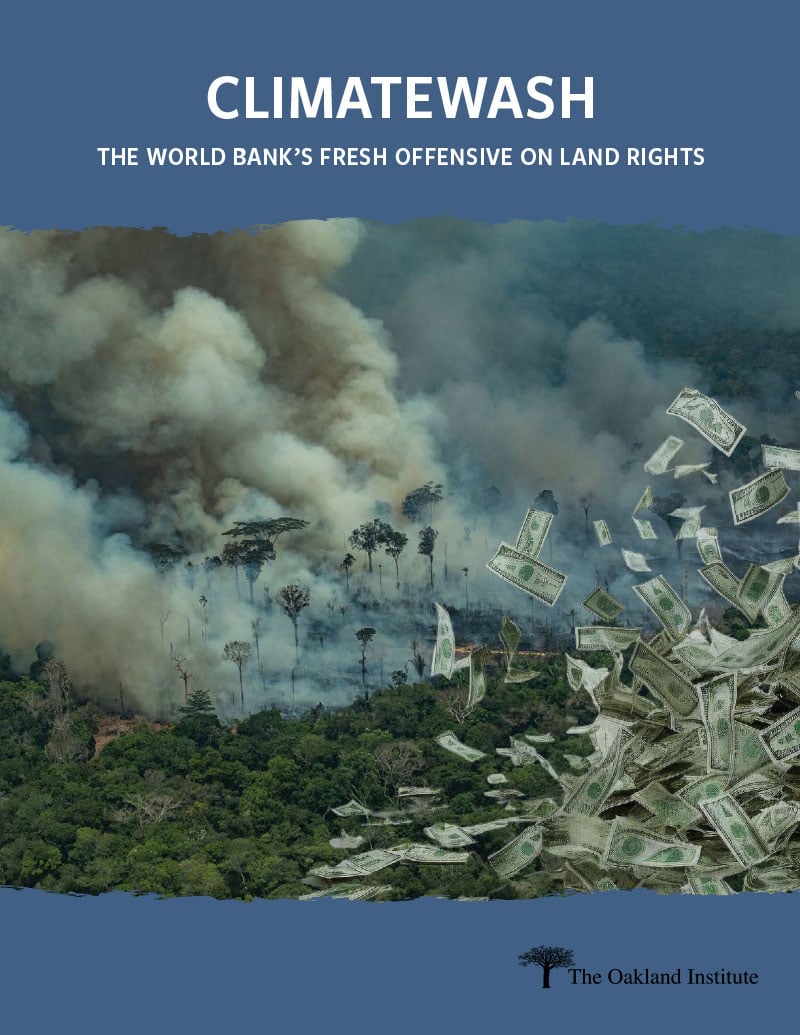

Climate wash: The World Bank’s Fresh Offensive on Land Rights

Published

3 months agoon

November 13, 2025

Climate wash: The World Bank’s Fresh Offensive on Land Rights reveals how the Bank is appropriating climate commitments made at the Conference of the Parties (COP) to justify its multibillion-dollar initiative to “formalize” land tenure across the Global South. While the Bank claims that it is necessary “to access land for climate action,” Climatewash uncovers that its true aim is to open lands to agribusiness, mining of “transition minerals,” and false solutions like carbon credits – fueling dispossession and environmental destruction. Alongside plans to spend US$10 billion on land programs, the World Bank has also pledged to double its agribusiness investments to US$9 billion annually by 2030.

This report details how the Bank’s land programs and policy prescriptions to governments dismantle collective land tenure systems and promote individual titling and land markets as the norm, paving the way for private investment and corporate takeover. These reforms, often financed through loans taken by governments, force countries into debt while pushing a “structural transformation” that displaces smallholder farmers, undermines food sovereignty, and prioritizes industrial agriculture and extractive industries.

Drawing on a thorough analysis of World Bank programs from around the world, including case studies from Indonesia, Malawi, Madagascar, the Philippines, and Argentina, Climatewash documents how the Bank’s interventions are already displacing communities and entrenching land inequality. The report debunks the Bank’s climate action rhetoric. It details how the Bank’s efforts to consolidate land for industrial agriculture, mining, and carbon offsetting directly contradict the recommendations of the IPCC, which emphasizes the protection of lands from conversion and overexploitation and promotes practices such as agroecology as crucial climate solutions.

Read full report: Climatewash: The World Bank’s Fresh Offensive on Land Rights

Source: The Oakland Institute

Related posts:

30 civil society organizations have written to the World Bank Group demanding to publicly disclose the Africa Energy Approach paper.

30 civil society organizations have written to the World Bank Group demanding to publicly disclose the Africa Energy Approach paper.

World Bank’s new scheme to privatize land in the developing world exposed

World Bank’s new scheme to privatize land in the developing world exposed

World Bank is backing dozens of new coal projects, despite climate pledges

World Bank is backing dozens of new coal projects, despite climate pledges

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

Communities Under Siege: New Report Reveals World Bank Failures in Safeguard Compliance and Human Rights Oversight in Tanzania

NGO WORK

Africa’s Land Is Not Empty: New Report Debunks the Myth of “Unused Land” and Calls for a Just Future for the Continent’s Farmland

Published

3 months agoon

November 13, 2025

A new report challenges one of the most persistent and harmful myths shaping Africa’s development agenda — the idea that the continent holds vast expanses of “unused” or “underutilised” land waiting to be transformed into industrial farms or carbon markets.

Titled Land Availability and Land-Use Changes in Africa (2025), the study exposes how this colonial-era narrative continues to justify large-scale land acquisitions, displacements, and ecological destruction in the name of progress.

Drawing on extensive literature reviews, satellite data, and interviews with farmers in Zambia, Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, the report systematically dismantles five false assumptions that underpin the “land abundance” narrative:

-

That Africa has vast quantities of unused arable land available for cultivation

-

That modern technology can solve Africa’s food crisis

-

That smallholder farmers are unproductive and incapable of feeding the continent

-

That markets and higher yields automatically improve food access and nutrition

-

That industrial agriculture will generate millions of decent jobs

Each of these claims, the report finds, is deeply flawed. Much of the land labelled as “vacant” is, in reality, used for grazing, shifting cultivation, foraging, or sacred and ecological purposes. These multifunctional landscapes sustain millions of people and are far from empty.

The study also shows that Africa’s food systems are already dominated by small-scale farmers, who produce up to 80% of the continent’s food on 80% of its farmland. Rather than being inefficient, their agroecological practices are more resilient, locally adapted, and socially rooted than the industrial models promoted by external donors and corporations.

Meanwhile, the promise that industrial agriculture will lift millions out of poverty has not materialised. Mechanisation and land consolidation have displaced labour, while dependency on imported seeds and fertilisers has trapped farmers in cycles of debt and dependency.

A Continent Under Pressure

Beyond these myths, the report reveals a growing land squeeze as multiple global agendas compete for Africa’s territory: the expansion of mining for critical minerals, large-scale carbon-offset schemes, deforestation for timber and commodities, rapid urbanisation, and population growth.

Between 2010 and 2020, Africa lost more than 3.9 million hectares of forest annually — the highest deforestation rate in the world. Grasslands, vital carbon sinks and grazing ecosystems, are disappearing at similar speed.

Powerful actors — from African governments and Gulf states to Chinese investors, multinational agribusinesses, and climate-finance institutions — are driving this race for land through opaque deals that sideline local communities and ignore customary tenure rights.

A Call for a New Vision

The report calls for a radical shift away from high-tech, market-driven, land-intensive models toward people-centred, ecologically grounded alternatives. Its key policy recommendations include:

-

Promoting agroecology as a pathway for food sovereignty, ecological regeneration, and rural livelihoods.

-

Reducing pressure on land by improving agroecological productivity, cutting food waste, and prioritising equitable distribution.

-

Rejecting carbon market schemes that commodify land and displace communities.

-

Legally recognising customary land rights, particularly for women and Indigenous peoples.

-

Upholding the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) for all land-based investments.

This report makes it clear: Africa’s land is not “empty” — it is lived on, worked on, and cared for. The future of African land must not be dictated by global capital or outdated development theories, but shaped by the people who depend on it.

Download the Report

Read the full report Land Availability and Land-Use Changes in Africa (2025) to explore the evidence and policy recommendations in detail.

Related posts:

Financial Institutions from Africa have made a monumental commitment of $100 billion to Africa’s green industrialization, a decision of immense significance that has the potential to shape Africa’s future.

Financial Institutions from Africa have made a monumental commitment of $100 billion to Africa’s green industrialization, a decision of immense significance that has the potential to shape Africa’s future.

Africa adopts the Africa Climate Innovation Compact (ACIC) Declaration to drive the continent towards innovative climate solutions.

Africa adopts the Africa Climate Innovation Compact (ACIC) Declaration to drive the continent towards innovative climate solutions.

One in three people sleeps on an empty stomach – World Bank Report.

One in three people sleeps on an empty stomach – World Bank Report.

Transforming Africa’s livestock sector is key to food security-Report

Transforming Africa’s livestock sector is key to food security-Report

Why govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry

Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

Evicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Will Uganda’s next government break the land-grabbing cycle?

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Swedish pension fund drops TotalEnergies amid rising EACOP risks

Land tenure security as an electoral issue: Museveni warns Kayunga land grabbers, reaffirms protection of sitting tenants.

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoWomen environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoUganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

-

FARM NEWS1 week ago

FARM NEWS1 week ago200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days agoEvicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days agoWitness Radio and Seed Savers Network are partnering to produce radio content to save indigenous seeds in Africa.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 day agoWhy govt is launching a comprehensive digital land registry