A chunk of Bugoma Central Forest Reserve is being cleared for sugarcane growing after NEMA gave the project a go-ahead, claiming the area was a grassland, an excuse conservationists say is fl awed. We look at the significance of Bugoma to the people of Bunyoro Kingdom and the region in general

Bugoma Central Forest is central to Bunyoro Kingdom and its people and culture, a Vision Group team discovered recently during a fact-fi nding mission, after part of the forest was leased to sugarcane growing. Not only is the forest part of the kingdom and its people, but has rare tree species too.

Over the years, the Banyoro have shown strong reverence to nature with a tradition of planting and preserving forests.

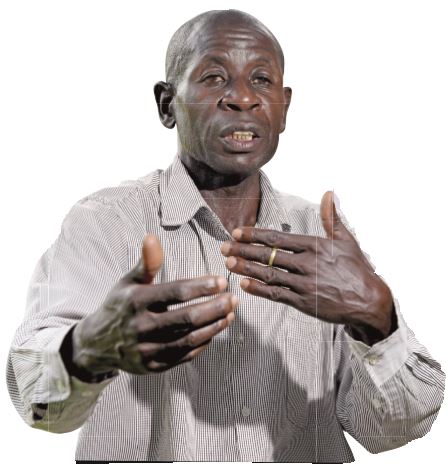

According to Apollo Rwamparo, the second deputy prime minister and minister of tourism in Bunyoro Kingdom, Bugoma and Budongo are cultural forests which were planted by Bunyoro kings, including the powerful Omukama Kabalega. However, Hoima Sugar Limited, which is seeking to cultivate sugarcane in part of Bugoma in Kikuube district, is disregarding such cultural importance.

KABALEGA’S FORESTS

According to Rwamparo, it is important to understand names such as Bugoma. He says the name Bugoma comes from drums.

“We have different drums, such as war drums and people would walk prepared for war,” he said, adding that Bugoma means a small drum. “Bugoma was partly planted with indigenous trees. Some of the tree species came from DR Congo and South Sudan. The trees were planted in Bugoma and parts of Budongo,” said.

He added, “This was the gene bank for Bunyoro region, so Bugoma and Budongo forests are cultural properties.” The trees in Budongo’s royal mile, where the Omukama used to train his army, Abarusura , and retired after his war expeditions, are still standing. Today, the area is a popular destination for visitors. “The royal mile was planted by Kabalega,” Rwamparo added.

He also said there are specific trees used in the making of canoes and for brewing local brew, known as mwenge bigere. The brew is extracted from bananas, then fermented to make alcohol.

“We have regalia and music instruments. They do not come from any piece of tree, there are specific trees in Bugoma and Budongo forest,” Rwamparo stressed.

He also pointed out that there was a lot of cultural coffee in Bugoma. “We have plenty of coffee in Bugoma,” he said, adding that there are also rattan , locally known as enga, which are used in the making of chairs and other furniture. The Bunyoro second deputy prime minister stated that totems of Banyoro are either animals or plants and most of them live in forests like Bugoma, explaining why the forest is treasured. “So when you destroy Bugoma, you are destroying the identity of Bunyoro,” he added.

KABALEGA’S PALACE

According to Rwamparo, Omukama Kabalega’s palace was located at Muhangazima, which is being turned into a sugar plantation by Hoima Sugar Limited in Bugoma forest reserve.

The Vision Group team also learnt about a tree species believed to have mystical powers and revered by the Banyoro. Locally named Mwitansowera, the trees grow in Bugoma and the surrounding areas. They are never touched or cut down, even the fearless and hardcore charcoal burners or illegal loggers do not dare bring them down. It is widely believed that Mwitansowera produces electric shocks that can kill anyone who gets close to it.

According to Peter Mautsi, a forest supervisor at Kisindi sector in Bugoma Central Forest Reserve, the trees (Mwitansowera species) are spared because many insects, including flies, are found dead near them and hence the name, Mwitansowera, literally translated to ‘killer of insects’.

It is believed that insects that approach it die of electric shocks emitted by the tree. Whether Mwitansowera produces electric shocks to prevent intrusion or not, the belief that it destroys anybody that goes close has been passed from one generation of Banyoro to another and it is supporting conservation. Fearing to be electrocuted, illegal loggers and charcoal burners have spared Mwitansowera from the chop.

But it is now feared that cutting part of Bugoma for sugarcane growing could see the end of the trees before modern scientists study its mystical powers.

The Vision Group team found out that no Munyoro dares cut Mwitansowera even when it is found outside the forest. It is said that upon approaching the tree, one finds dead insects littered under it, which locals use to confi rm their belief that the tree emits electric shocks.

CLAN PUTS UP FIGHT

Not far from the cultural treasure of Bugoma, a clan known as Kwonga is conserving a forest sitting on part of their land at Kitoole village in Kabwoya sub-county, Hoima district. This is about 40km from Hoima, along the Hoima-Kyenjojo road.

The forest is largely intact and is estimated to cover over 100 acres. The Kwonga is one of the clans in Bunyoro Kitara Kingdom, whose totem is the bushbuck (one of the antelopes). The clan elders have established a legacy of handing over, from one generation to generation, a natural forest called Kwonga clan forest.

“Not only did the old men pass the forest to us, they also left behind over two square kilometres of land, where our clan members have lived for generations,” Dezi Irumba, one of the clan leaders, said.

Currently, Kwonga forest is better kept than the nearby Bugoma forest. Kwonga forest looks intact as opposed to Bugoma, which has become a theatre of destruction. Given that the only forest patch that is left is 4km away, Kwonga forest has become a refugee for the birds that were dispersed after destruction of the natural forests on private land.

The forest is also a catchment for rivers, springs and streams. It has one permanent spring well called Kamwiruki which was used as a source of water by the great grandparents of the Kwonga clan. The forest provides a catchment for three rivers; Nyakabaale, Waniaha and Wamparamba, all of which originate from Mpanga Central Forest Reserve, located 4km east of Bugoma.

The rivers feed Wambabya, where the 9MW Kabalega dam has been constructed. Wambabya empties into Lake Albert. The Kwonga people’s practice of conserving forests is similar to that of the people of Kilifi in Kenya.

In Kilifi, north of Mombasa, a coastal clan known as the Kayas have conserved their forests for generations. The forests stretch from northern Kenya to southern Africa. The Kayas have preserved their forests and handed them from one generation to another.

The Kayas do not bury their dead in coffi ns and concrete graves. So, the bodies that have taken nutrients from the earth have to return them. As the clans conserve the forests, they also conserve water sources and also provide carbon sinks, which absorb emissions blamed for causing climate change.

**New Vision