SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Conservation Concessions as Neo-Colonization: The African Parks Network

Published

4 years agoon

The conservation industry is now promoting the idea of ‘buying up’ Conservation Concessions and reconstituting them as business models with profit-seeking aims. A case in point is the ‘African Parks Network’, which manages 19 National Parks and Protected Areas in 11 countries in Africa.

Concessions for so-called conservation purposes (national parks, protected areas, nature reserves, etc.) have their roots in the ideas and beliefs that underpinned European colonisation. The concept of Protected Areas originated in the United States in the late 1800s, founded on the desire to preserve ‘intact’ areas of ‘wilderness’ without human presence, mainly for elite hunting and the enjoyment of scenic beauty. Both Yellowstone and Yosemite national parks were forcibly emptied of their inhabitants and provided the blueprint for ‘doing conservation’ that continues to the present day. During that same period, European colonisers declared large tracts of the occupied territories in Africa as ‘game reserves’ after forcibly displacing populations from said areas. These reserves were often created after colonialist hunters had already exterminated much of the wildlife population, in an effort to restore such populations so that they could continue ‘big game hunting.’

However, the withdrawal of European colonisers from Africa did not bring about a return to customary land tenure. Newly formed States often continued the land use and conservation policies of the colonisers, which demonstrates how deep colonial norms and knowledge systems had become institutionalised. Colonisation processes have always been accompanied by the idea that ‘nature’ is separate from humans, and that ‘civilisation’ is better than the unpredictable and unproductive ‘wilderness’. The idea of creating areas of ‘nature without humans’ is thus rooted in the racist and colonial thinking that only white ‘civilised’ men were able to protect and manage this ‘nature’. They and only they could enter this otherwise ‘human-free’ ‘nature’.

And we can observe that in many places, this idea persists even today. Safari tourism, for example, is simply a continuation of this tradition. Wealthy (predominantly white) tourists are paying large sums of money to stay in luxury hotels and receive permission to shoot animals (with guns or cameras) as trophies. Meanwhile, those populations that hunt for subsistence inside their territories-turned-park are labelled as poachers and criminalised. Such tourism relies on certain constructions of what ‘Africa’ means to those undertaking the safaris, which reveal the colonial mindset that created these reserves in the first place. That is why protected areas are mostly ‘people-free’ landscapes. People are rarely portrayed as an intrinsic part of nature, and if they are, they are depicted either as intruders or ‘poachers’, or as touristic landscapes for buying handcrafts or watching dances, or as guides or eco-guards working for a foreign company or NGO.

Most international conservation NGOs have facilitated this depiction of Indigenous Peoples as invaders in their own territories. This narrative has conveniently placed their focus on fighting against people using the forest for their own subsistence, instead of on the consumption patterns and economic interests of the supporters and funders of said NGOs.

The Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, for example, is arguably the best-known symbol of ‘Africa’s wild nature’. Yet, there is hardly any mention in the Park’s tourist propaganda on how the Serengeti was created: by evicting the Indigenous Maasai during colonial times from their ancestral territories. And this situation continues today. (1)

Mordecai Ogada, co-author of the book ‘The Big Conservation Lie’, explains in a 2021 interview that the geographical spaces of Protected Areas frequently work as colonies, with the difference that they are no longer under the management of an empire but of a network of elites with clear economic and political interests. (2) Those, he explains, are the colonisers with respect to conservation concessions. They enter such agreements with large sums of money and frequently influence any national policy that might impact their interests and managed areas. The power of these networks of colonisers is both physical –enforcing their rule and dominance on the ground- and political -having allies in the right places administering key governmental offices and funding positions, Ogada explained. On top of this, possible conflicts that may arise are easily brushed aside as not their responsibility; this is done by placing the burden on the ‘sovereign condition’ of national governments. These networks answer to donors, the tourist industry and tourists themselves, which are all mainly based in the global North. And they endure on the basis of images of peaceful landscapes, which in their imaginations are landscapes without people.

These networks also involve powerful business people with vested interests in financing conservation for offsetting their emissions or greenwashing their dirty and destructive activities. Recent examples include the internet retailer Amazon’s CEO Jeff Bezos and his ten-billion-dollar ‘Earth Fund’, with some of the biggest conservation NGOs receiving $100 million each in a first round of payments (3), and Swiss billionaire businessman Hansjörg Wyss’s donations to the so-called ‘30×30’ scheme (4), which aims for 30 per cent of the planet to be turned into Protected Areas by 2030.

Nowadays, the conservation industry is promoting the idea of ‘buying up’ conservation concessions (Protected Areas or Parks) and reconstituting them as business models with profit-seeking aims. A case in point is the ‘African Parks Network’ (APN), which manages 19 National Parks and Protected Areas in 11 countries in Africa.

The African Parks Network: Outsourcing Protected Areas to Private Companies

The ‘African Parks Network’ (APN) was founded by billionaire Dutch tycoon Paul Fentener van Vlissingen in the year 2000. Its founding name was the African Parks Foundation. Fentener comes from one of the Netherlands’ richest industrial dynasties and was CEO of the energy conglomerate SHV Holdings, which undertook business with the apartheid regime in South Africa. He allegedly had the idea for creating ‘African Parks’ after a dinner hosted by Nelson Mandela in the presence of Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands, at which the future of national parks in South Africa was discussed. For the billionaire, it was the perfect opportunity to restore his image, tainted by his activities during the apartheid regime. Initially created as a commercial company, ‘African Parks’ swapped this status for that of an NGO in 2005, in order to more easily attract donors and conservation funding. (5)

APN’s business model is based on a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) strategy for the management of Protected Areas, whereby APN maintains the full responsibility and execution of all management functions and is accountable to the government. APN employs a market approach to wildlife conservation, arguing that wildlife can pay for its conservation if ‘well managed’. It presents itself as an “African solution for Africa’s conservation challenges”. (6) However, behind the façade of APN is a large group of northern and southern governments, multilateral institutions, international conservation organisations, millionaire family foundations and individuals that fund its conservation business.

Since 2017, the president of the company is Prince Henry of Wales, otherwise known as Prince Harry, a member of the British royal family, who has helped in the acquisition of funding and partners.

APN controls a total area of 14.7 million hectares in Africa, about half the size of Italy, and it intends to expand even more in order to manage “30 parks by 2030 across 11 biomes, ensuring that 30 million hectares are well managed, thus contributing to the broader vision of having 30% of Africa’s unique landscapes protected in perpetuity”. Moreover, their roadmap to 2030 states that “10 more protected areas spanning a further five million hectares will be managed by select partners through our newly created ‘Incubator Programme’. These objectives are ambitious and will contribute significantly to the global target of protecting 30% of the Earth to keep the planet flourishing”. (7)

The Network also indicates its interest in selling carbon credits as an additional source of income. Although such credits basically facilitate more pollution and fossil fuel burning, the website of APN claims that its conservation model “represents an integrated nature-based solution to climate change (…). We secure the carbon captured in the plants and soil in places of high biodiversity value”. (8)

However, experiences on the ground reveal how this so-called Public-Private ‘partnership’ is in fact reinforcing and recreating oppressive power relations.

A 2016 academic study on the Majete Wildlife Reserve in Malawi is a case in point. (9) The reserve has been managed by APN since 2003, with a 25 year management concession. It was the first park to fall under APN’s administration. According to the concession they were granted, APN is supposed to involve community members in the management of the reserve. This includes consulting them in issues requiring critical decisions such as bringing new animals into the area, and allowing said members to access and use some of the resources in the reserve such as grass, fish and reeds.

While there is a formal and legal partnership between the Malawian government and APN on the sharing of proceeds, there is no formal or clear agreement between local communities and APN on how benefits are going to be shared out. The benefits for the communities are only indirect, by engaging in activities such as selling food and performing dances for a tourist public. APN argues that apart from physically accessing the resources from the game reserve, communities will benefit from wildlife conservation through employment, income-generating activities they are engaged in and via APN’s corporate responsibility initiatives. However, according to the research, communities are rarely allowed to fish, or to harvest honey or reeds in the game reserve. Instead, they are allowed to harvest only grass at specific times of the year, with the Park management putting forth the argument that communities are supposed to protect and conserve these areas, and that such harvesting disturbs the animals.

One woman interviewed for the research was reported as saying “we have lost control over our means of livelihood, but cannot also get employed by APN; we are prevented from accessing resources that we need for our daily subsistence life such as fish, mushrooms and honey.”

The same research also underlines how APN deceptively used local people to achieve its own goals, but in such a way as to be of no benefit to the community as a whole. For example, APN used a vague agreement with local chiefs (who were taken to other national parks for a tour) as justification to enforce an extension of the wildlife reserve to ancestral land that was being farmed by the communities. This left community members not only voiceless but also divided. This situation has been worsened even more by APN’s tactic to coerce families, and women in particular, by offering to cover their children’s school fees.

Interviews with local chiefs and leaders of community organisations also revealed that though they are informed about the new developments inside the reserve, they do not have any powers to object to APN’s management decisions. Consequently, they are forced to align themselves with the APN management for fear of jeopardising their relationship with the organisation.

The Odzala-Kokoua National Park in the Republic of Congo is another case that merits being highlighted. The Park, created in 1935 when the country was a French colony, appropriated the biggest forest area in the region with 1.35 million hectares. Since 2010, the management of this “nirvana for nature lovers”, as APN describes it, has been placed entirely in APN’s hands for a period of 25 years. The partners of the Park include groups such as WWF and the European Union.

APN partnered with the Congo Conservation Company (CCC), an enterprise created and funded by a German philanthropist, in order to undertake tourist business activities in the Odzala-Kokoua National Park. This includes three high-end lodges, which tourists can access by flying in on charter flights from the Congolese capital Brazzaville. However, very few inhabitants of Brazzaville have the possibility to enjoy such luxury tourism. A 4-day Odzala Gorilla Discovery Camp visit, for example, costs US$ 9,690 dollars per person.

While the Park was founded in 1935, APN states that “humans have occupied the area for 50,000 years”. The company notes that 12,000 people still live around the Park, “yet it is still one of the most biologically diverse and species-rich areas on the planet” (emphasis added). With this formulation, rather than recognising the inhabitants’ contribution towards keeping the forest standing after all these thousands of years, the company makes it clear that in its view, the presence of people is not compatible with the aim of conserving forests; it is despite the communities’ presence that there is still some remaining biodiversity. (10)

APN claims to protect the Park “with an enhanced eco-guard team and other law enforcement techniques”, besides investing in “changing human behaviour”. These claims and views on conservation make clear that for this Network and its funders and allies, people living in and around forests are considered a threat and that their conservation business can be run better without them.

In fact, according to a study about the historical relationship between communities and the Park’s management, an estimated 10,000 people were evicted following the Park’s creation in 1935, and have never been compensated for their loss. The study also points out that in spite of the more recent policy of APN that suggests ‘participation’ and ‘representation’ of communities in decision-making processes, the general feeling among the communities interviewed is that the Park has been set up not only by foreigners but also for foreigners. Some community members said: “We don’t want this park that gives us nothing and diminishes our livelihoods; it deprives us from our rights over the forest. Our rights to access resources and lands are very weakly respected”. Another person said: “Our game is seized by eco-guards. There is more misery and poverty, because not only are we unable to feed ourselves well, we also cannot sell a bit of game to buy basic products such as soap and petrol”. (11)

It should be no surprise that for more than 10 years, APN has shown an interest in exploring if the Odzala-Kokoua Park could be turned into a REDD+ project, because through the lens of such projects, communities are also considered a threat and blamed for deforestation. (12) Furthermore, there are no provisions for communities to receive a share of the profits from the sale of carbon credits.

For the WWF, people and not mining companies are threatening the forests

The Odzala-Kokoua National Park is not the only park in the region. It is part of what WWF calls the ‘Tridom Landscape’, an area covering 10 per cent of the whole Congo Basin rainforest, which includes another two Parks: the Dja Faunal Reserve in Cameroon and the Minkébé National Park in Gabon. But several large-scale projects are planned inside the ‘Tridom Landscape’, in particular an area of 150,000 hectares for iron ore mining concessions in the Cameroon-Congo border region. Due to the inaccessibility of said region, huge infrastructure investments must also be planned, such as roads, a railway to transport the minerals, and a hydro-dam for supplying the necessary electricity. The latter is called the Chollet Dam, named after a stretch of waterfalls on the Dja river, described by WWF itself as “a pristine site”. (13)

WWF has been practicing and conniving with persecution and eviction of Indigenous Peoples and other communities in the region in the name of ‘protecting’ nature. Yet, no similar measures have been announced by the NGO against the companies promoting mining, large-scale infrastructures and hydroelectric dams in this same area. The explanation can be found in a recent (rejected) project proposal that WWF presented to the EU to create yet another Protected Area, the Messok Dja Park.

In this proposal, WWF argues that it expects the mining companies to fund WWF in its ‘protection measures’ in the Triodom area. In other words, the new Park could be seen as an offset for the damage done by mining and its related infrastructure. On top of this, eco-guards supported by WWF have been involved in severe human rights violations, including beatings, torture, sexual abuse and even the killing of members of indigenous communities who live in Messok Dja, the new Park that is being proposed. (14)

The tremendous contradiction of persecuting those who have lived with and conserved forests while remaining silent about the mining companies’ plans, reveals the real interests of current ‘conservation’ policies, namely, the continuation of an overall destructive model based on the ideas and beliefs of colonisation processes and the colonisers, old and new. Solidarity with the communities that resist and face the impacts of ‘fortress conservation’ is imperative. Enterprises such as APN represent and reinforce these ‘fortress conservation’ beliefs and policies.

WRM International Secretariat

(1) REDD-Monitor, Stop the evictions of 70,000 Maasai in Loliondo, Tanzania, January 2022.

(2) Death in the Garden Podcast, Dr. Mordecai Ogada (Part 2) – A case for scrutinizing the climate narrative, November 2021

(3) CNBC, Jeff Bezos names first recipients of his $10 billion Earth Fund for combating climate change, November 2020

(4) The Nature Conservancy, 30×30: Protect 30% of the Planet’s Land and Water by 2030, February 2020.

(5) Le Monde Diplomatique, From apartheid to philanthropy, February 2020

(7) Idem (6)

(8) African Parks, Climate Action

(9) Sane Pashane Zuka, Brenda-Kanyika Zuka. Traitors Among Victims.

(10) WRM Bulletin, September 2021, The Sangha Region in the Republic of Congo.

(11) Rainforest Foundation, Protected areas in the Congo Basin: Failing both people and biodiversity?, 2016.

(12) REDD-Monitor, African Parks Network plans to sell carbon from Odzala-Kokoua National Park in Republic of Congo, 2011.

(13) REDD-Monitor, TRIDOM – one of the largest trans-boundary wildlife areas in Africa faces critical new threats. Far from protesting, conservationists are looking to cash-in on the destruction, 2022.

(14) Idem 13

Original Source: World Rainforest Movement

Related posts:

Govt told to urgently resettle people evicted from national parks

Govt told to urgently resettle people evicted from national parks

US government stops funding to WWF, WCS and other conservation organisations because of human rights abuses

US government stops funding to WWF, WCS and other conservation organisations because of human rights abuses

WWF apologises for human rights abuse allegations and commits to an indigenous-led approach to global conservation

WWF apologises for human rights abuse allegations and commits to an indigenous-led approach to global conservation

Colonization and Monoculture Plantations: Histories of Large-Scale ‘Grabbings’

Colonization and Monoculture Plantations: Histories of Large-Scale ‘Grabbings’

You may like

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

‘Food and fossil fuel production causing $5bn of environmental damage an hour’

Published

2 months agoon

December 22, 2025

UN GEO report says ending this harm key to global transformation required ‘before collapse becomes inevitable’.

Related posts:

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

Activists storm TotalEnergies’ office ahead of G20 Summit, demand end to fossil fuel expansion in Africa

New billion-dollar loans to fossil fuel companies from SEB, Nordea and Danske Bank.

New billion-dollar loans to fossil fuel companies from SEB, Nordea and Danske Bank.

Fossil fuel opponents lobby Africans for support

Fossil fuel opponents lobby Africans for support

Ecological land grab: food vs fuel vs forests

Ecological land grab: food vs fuel vs forests

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

Britain, Netherlands withdraw $2.2 billion backing for Total-led Mozambique LNG

Published

2 months agoon

December 17, 2025

CONSTRUCTION HALTED IN 2021, BUT DUE TO RESTART

PROJECT CAN PROCEED WITHOUT UK, DUTCH FINANCING, TOTAL HAS SAID

CRITICISM FROM ENVIRONMENTAL, HUMAN RIGHTS GROUPS

Related posts:

Uganda, Total sign crude oil pipeline deal

Uganda, Total sign crude oil pipeline deal

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

Witness Radio – Uganda, Community members from Mozambique and other organizations around the world say NO to more industrial tree plantations

NGOs file suit against Total over Uganda oil project

NGOs file suit against Total over Uganda oil project

Agribusiness Company with financial support from UK, US and Netherlands is dispossessing thousands.

Agribusiness Company with financial support from UK, US and Netherlands is dispossessing thousands.

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS

The secretive cabal of US polluters that is rewriting the EU’s human rights and climate law

Published

3 months agoon

December 5, 2025

Leaked documents reveal how a secretive alliance of eleven large multinational enterprises has worked to tear down the EU’s flagship human rights and climate law, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). The mostly US-based coalition, which calls itself the Competitiveness Roundtable, has targeted all EU institutions, governments in Europe’s capitals, as well as the Trump administration and other non-EU governments to serve its own interests. With European lawmakers soon moving ahead to completely dilute the CSDDD at the expense of human rights and the climate, this research exposes the fragility of Europe’s democracy.

Key findings

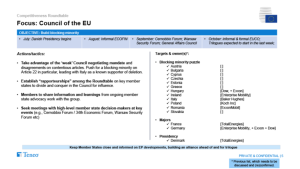

- Leaked documents reveal how a secretive alliance of eleven companies, including Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Koch, Inc., has worked under the guise of a “Competitiveness Roundtable” to get the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) either scrapped or massively diluted.

- The companies, most of which are headquartered in the US and operate in the fossil fuel sector, aimed to “divide and conquer in the Council”, sideline “stubborn” European Commission departments, and push the European People’s Party (EPP) in the European Parliament “to side with the right-wing parties as much as possible”.

- Chevron and ExxonMobil were in charge of mobilising pressure against the CSDDD from non-EU countries. The Roundtable companies endeavoured to get the CSDDD high on the agenda of the US-EU trade negotiations and also worked on mobilising other countries against the CSDDD, in order to disguise the US influence.

- Roundtable companies paid the TEHA Group – a think tank – to write a research report and organise an event on EU competitiveness, which echoed the Roundtable’s position and cast doubt on the European Commission’s assessment of the economic impact of the CSDDD.

While Europeans were told that their governments were negotiating a landmark law to hold corporations accountable for human rights abuses and climate damage, a secretive alliance of US fossil fuel giants was working behind the scenes to destroy it. Collaborating under the innocent-sounding name ‘Competitiveness Roundtable’, eleven multinational enterprises have worked closely to eviscerate several EU sustainability laws, including the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). This Competitiveness Roundtable may be unknown, but its members are a who’s-who of polluting, mainly US, multinationals, including Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Dow. The group seems to have run rings around all branches of the EU and the Trump administration to get what they want: scrapping, or at least hugely diluting, the CSDDD.

Leaked documents obtained by SOMO reveal how, under the pretext of the now-near-magical concept of ‘competitiveness’, these companies plotted to hijack democratically adopted EU laws and strip them of all meaningful provisions, including those on climate transition plans, civil liability, and the scope of supply chains. EU officials appear not to have known who they were up against. But the documents obtained by SOMO show a high level of organisation and strategising with a clear facilitator: Teneo, a US public relations and consultancy company.

The documents indicate that many of the companies involved wanted to stay hidden from view. After all, if it were widely known that a secretive group of mostly American fossil fuel companies like Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Koch, Inc. was working as a coordinated organisation to dilute an EU climate and human rights law, that might raise questions and serious concern among the public and the policymakers they were targeting. Many of the companies in the Roundtable have never publicly spoken out against the CSDDD.

Big Oil’s ‘Competitiveness Roundtable’

The Competitiveness Roundtable is dominated by fossil fuel companies, including three Big Oil companies (ExxonMobil, Chevron, TotalEnergies) and three other companies with activities in the oil and gas sector (Koch, Inc., Honeywell, and Baker Hughes). Other members are Nyrstar (minerals and metals, a subsidiary of Trafigura Group); Dow, Inc. (chemicals); Enterprise Mobility (car rentals); and JPMorgan Chase (finance).

Teneo, the Roundtable’s coordinator, has a track record(opens in new window) of working with fossil fuel companies, including Chevron, Shell, and Trafigura, and was hired by the government of Azerbaijan to handle public relations(opens in new window) when it hosted the COP29 climate conference.

In February 2025, the European Commission published the Omnibus I proposal(opens in new window), which aims to “simplify” several EU sustainability laws, including the CSDDD. The documents obtained by SOMO reveal that the Roundtable companies, which have been meeting weekly since at least March 2025, worked on deep interventions within each of the three EU institutions to get the Omnibus I package to align exactly with their views. The EU institutions are expected to reach a final agreement on Omnibus I by the end of 2025.

The documents reveal that the Roundtable companies’ activities in the Parliament are far more significant than what is visible in the EU Transparency Register(opens in new window). Eight of the Roundtable’s lobbying meetings during the Strasbourg plenary sessions of May and June 2025, listed in the Transparency Register, show Teneo as the only attendee, thereby failing to disclose the names of other Roundtable companies that participated in these meetings. Another three meetings the Roundtable held were not found in the EU Transparency Register(opens in new window) at all.

“Divide and conquer” the Council

In the European Council, the Roundtable plotted to “divide and conquer” EU governments to get the climate article in the CSDDD deleted. In June 2025, during the final weeks of negotiations in the Council on the Omnibus I proposal, the Roundtable discussed lobbying EU government leaders to “intervene politically” to ensure its priorities were included in the Council’s negotiation mandate. Subsequently, German Chancellor Merz and French President Macron reportedly(opens in new window) personally intervened(opens in new window) in the Council’s political process, leading to a dramatic dilution(opens in new window) of the texts(opens in new window) negotiated in the months before the intervention. Several of the changes made to the texts strongly align with the Roundtable’s demands, including delaying and substantially weakening the climate obligations, scrapping EU civil liability provisions, and limiting the responsibility of companies to take responsibility for their supply chains (the ‘Tier 1’ restriction).

Competitiveness Roundtable meeting document, 11 July 2025.

Additionally, the documents reveal that the Roundtable is still aiming to drum up a “blocking minority” to overturn the Council’s negotiation mandate during the trilogue negotiations, which started in November 2025. By “tak[ing] advantage of the ‘weak’ Council negotiating mandate” and disagreements between EU Member States on “contentious articles”, the Competitiveness Roundtable companies hope to force the Danish Council presidency to give up on including any form of climate obligations in the CSDDD – despite EU Member States’ agreement on this in the June 2025 Council mandate(opens in new window) .

To implement the divide-and-conquer strategy, the Roundtable assigned specific companies to “establish rapporteurships” with different EU governments. TotalEnergies would target the French, Belgian, and Danish governments, and ExxonMobil would target Germany, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Romania.

Circumventing “stubborn” European Commission departments

The Roundtable also discussed working on “circumvent[ing]” two “stubborn” European Commission departments involved in the Omnibus political process, DG JUST and DG FISMA, which, in their view, were “unlikely to be willing to see our side of the story”. According to the documents, DG JUST opposed deleting the climate article and restricting the Directive’s scope to only very large enterprises. The Roundtable aimed to diminish the role of these departments by pressuring President Von der Leyen and Commissioners McGrath (DG JUST) and Albuquerque (DG FISMA) by “organising letters from Irish and German business groups” and using an event held by the European Roundtable for Industry to “target” Von der Leyen and McGrath.

Read full report: Somo.nl

Source: Somo

Related posts:

Victims of human rights violations in Uganda still waiting for redress

Victims of human rights violations in Uganda still waiting for redress

UN Human Rights Chief urges EU leaders to approve key business and human rights legislation

UN Human Rights Chief urges EU leaders to approve key business and human rights legislation

Business, UN, Govt & Civil Society urge EU to protect sustainability due diligence framework

Business, UN, Govt & Civil Society urge EU to protect sustainability due diligence framework

Development financiers fuel human rights abuses – New Report

Development financiers fuel human rights abuses – New Report

UPDF General on the spot over fresh evictions in Hoima

Small-scale fishers and coastal communities are pushing to testify before a human rights commission investigating the causes of food inequality in South Africa.

The Kenyan government insists on maintaining provisions of the Seed Act that the court nullified: farmers and legal experts question the motive.

FEATURE: What Lagos Can Learn From Kenya, Morocco, Uganda’s Forced Evictions

Women environmental rights defenders in Africa are at the most significant risk of threats and attacks – ALLIED New report

Uganda moves toward a Bamboo Policy to boost environmental conservation and green growth.

Evicted from their land to host Refugees: A case of Uganda’s Kyangwali refugee settlement expansion, which left host communities landless.

200 farmers demonstrate at parliament, worried about new seed monopoly

Innovative Finance from Canada projects positive impact on local communities.

Over 5000 Indigenous Communities evicted in Kiryandongo District

Petition To Land Inquiry Commission Over Human Rights In Kiryandongo District

Invisible victims of Uganda Land Grabs

Resource Center

- Land And Environment Rights In Uganda Experiences From Karamoja And Mid Western Sub Regions

- REPARATORY AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MUST BE AT THE CORE OF COP30, SAY GLOBAL LEADERS AND MOVEMENTS

- LAND GRABS AT GUNPOINT REPORT IN KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT

- THOSE OIL LIARS! THEY DESTROYED MY BUSINESS!

- RESEARCH BRIEF -TOURISM POTENTIAL OF GREATER MASAKA -MARCH 2025

- The Mouila Declaration of the Informal Alliance against the Expansion of Industrial Monocultures

- FORCED LAND EVICTIONS IN UGANDA TRENDS RIGHTS OF DEFENDERS IMPACT AND CALL FOR ACTION

- 12 KEY DEMANDS FROM CSOS TO WORLD LEADERS AT THE OPENING OF COP16 IN SAUDI ARABIA

Legal Framework

READ BY CATEGORY

Newsletter

Trending

-

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks agoUS-DRC Strategic Partnership Agreement Faces Constitutional Challenge in Court

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoIndigenous communities’ complaint against World Bank-linked Nepal Cable Car Project declared eligible for investigation.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoDecades of land loss and chronic poverty: Salala Rubber Plantation prioritizes profit over the well-being of local Liberian communities.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks agoThe Witness Radio and Seed Savers Network Joint Radio program boosts Farmers’ knowledge of seed and food sovereignty.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week agoFEATURE: What Lagos Can Learn From Kenya, Morocco, Uganda’s Forced Evictions

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago13 years after the refugee host community was forcefully evicted to expand a refugee settlement, thousands remain unsettled.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days agoThe Kenyan government insists on maintaining provisions of the Seed Act that the court nullified: farmers and legal experts question the motive.

-

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days agoSmall-scale fishers and coastal communities are pushing to testify before a human rights commission investigating the causes of food inequality in South Africa.