A new report challenges one of the most persistent and harmful myths shaping Africa’s development agenda — the idea that the continent holds vast expanses of “unused” or “underutilised” land waiting to be transformed into industrial farms or carbon markets.

Titled Land Availability and Land-Use Changes in Africa (2025), the study exposes how this colonial-era narrative continues to justify large-scale land acquisitions, displacements, and ecological destruction in the name of progress.

Drawing on extensive literature reviews, satellite data, and interviews with farmers in Zambia, Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, the report systematically dismantles five false assumptions that underpin the “land abundance” narrative:

-

That Africa has vast quantities of unused arable land available for cultivation

-

That modern technology can solve Africa’s food crisis

-

That smallholder farmers are unproductive and incapable of feeding the continent

-

That markets and higher yields automatically improve food access and nutrition

-

That industrial agriculture will generate millions of decent jobs

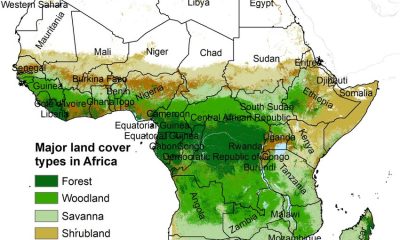

Each of these claims, the report finds, is deeply flawed. Much of the land labelled as “vacant” is, in reality, used for grazing, shifting cultivation, foraging, or sacred and ecological purposes. These multifunctional landscapes sustain millions of people and are far from empty.

The study also shows that Africa’s food systems are already dominated by small-scale farmers, who produce up to 80% of the continent’s food on 80% of its farmland. Rather than being inefficient, their agroecological practices are more resilient, locally adapted, and socially rooted than the industrial models promoted by external donors and corporations.

Meanwhile, the promise that industrial agriculture will lift millions out of poverty has not materialised. Mechanisation and land consolidation have displaced labour, while dependency on imported seeds and fertilisers has trapped farmers in cycles of debt and dependency.

A Continent Under Pressure

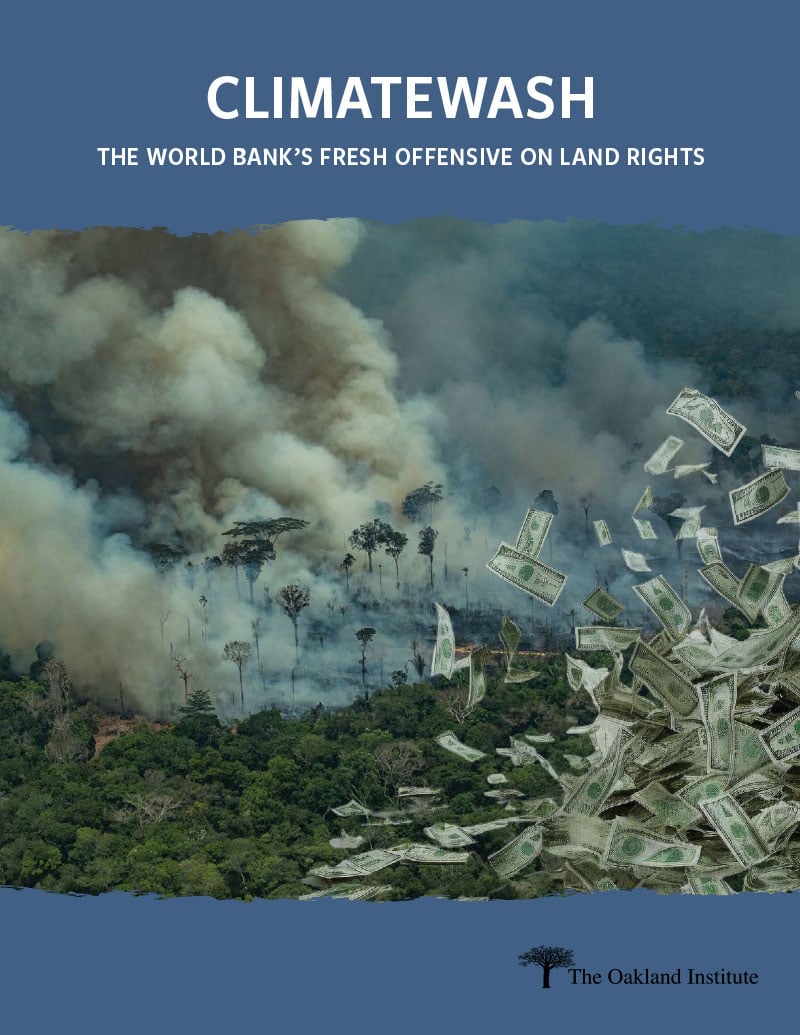

Beyond these myths, the report reveals a growing land squeeze as multiple global agendas compete for Africa’s territory: the expansion of mining for critical minerals, large-scale carbon-offset schemes, deforestation for timber and commodities, rapid urbanisation, and population growth.

Between 2010 and 2020, Africa lost more than 3.9 million hectares of forest annually — the highest deforestation rate in the world. Grasslands, vital carbon sinks and grazing ecosystems, are disappearing at similar speed.

Powerful actors — from African governments and Gulf states to Chinese investors, multinational agribusinesses, and climate-finance institutions — are driving this race for land through opaque deals that sideline local communities and ignore customary tenure rights.

A Call for a New Vision

The report calls for a radical shift away from high-tech, market-driven, land-intensive models toward people-centred, ecologically grounded alternatives. Its key policy recommendations include:

-

Promoting agroecology as a pathway for food sovereignty, ecological regeneration, and rural livelihoods.

-

Reducing pressure on land by improving agroecological productivity, cutting food waste, and prioritising equitable distribution.

-

Rejecting carbon market schemes that commodify land and displace communities.

-

Legally recognising customary land rights, particularly for women and Indigenous peoples.

-

Upholding the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) for all land-based investments.

This report makes it clear: Africa’s land is not “empty” — it is lived on, worked on, and cared for. The future of African land must not be dictated by global capital or outdated development theories, but shaped by the people who depend on it.

Download the Report

Read the full report Land Availability and Land-Use Changes in Africa (2025) to explore the evidence and policy recommendations in detail.

Source: Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA)

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago