Over the past five years, at least two people from rural communities have been killed weekly in the struggles against land grabs, based on estimates by the Pesticide Action Network Asia Pacific (PANAP). More than eight are arrested and detained weekly, and more than two are harassed or assaulted.

On Sept. 2, Nigerian security forces and police arrived on a boat in the village of Agbede. They fired in the air to scatter the villagers and then burned at least nine houses.

On June 15, a violent confrontation between the Paraguay police and farmers in the town of Edelira ended with the killing of Édgar Centurión, a local farmer.

On June 12, the police arrested 91 people, including several members of a local peasant group, in Hacienda (a large estate or plantation) Tinang in a Philippine province. Eighty-three were detained and charged with trumped-up cases of illegal assembly and obstruction of justice, among others.

Systematic attacks

These attacks on rural communities are not isolated incidents of violence. They form part of the systematic repression of peasants fighting land grabs by big foreign corporations and the local elite.

The Agbede case, for instance, is tied to the ongoing land conflict between the local people and the Okomu Oil Palm Company (OOPC). The people claim that OOPC grabbed their lands and blocked their villages’ only public road. OOPC is a unit of the Socfin Group, a Luxembourg-based palm oil and rubber plantation operator notorious for its ruthless methods against local communities. Aside from Nigeria, Socfin units operate in Cameroon, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire, and Cambodia, among others.

Meanwhile, a land dispute between some 80 farming families and an agro-livestock firm is the backdrop of Centurión’s killing. Armed with shotguns, the local police destroyed the homes and crops of the settlement where Centurión lived to clear the land for the company. When the farmers resisted, the police opened fire, resulting in the 29-year-old farmer’s death.

The mass arrests in Hacienda Tinang happened amid a nearly three-decade dispute over 200 hectares of land between 236 peasant beneficiaries of the government’s land reform program and an influential political clan, which includes the incumbent town mayor. The farmers and their supporters were doing a collective farming activity as part of the assertion of their right to the disputed land when the police dispersed and arrested them.

Two killings a week

Over the past five years, at least two individuals from rural communities have been killed weekly in struggles against land grabbing, based on estimates by the PAN Asia Pacific (PANAP). More than eight are arrested and detained, and more than two are harassed or assaulted weekly.

Under its No Land, No Life! campaign, PANAP has been monitoring cases of human rights violations (HRVs) against farmers, farm workers, indigenous people, and land activists. From January 2017 to the latest available data (as of Oct. 20, 2022), PANAP has monitored 417 cases of killings that resulted in 610 deaths. Of the victims, 238 or 39 percent were farmers.

During the same period, there were 260 cases of arrests and detention, with 2,565 victims, and farmers comprised 45 percent of the total. For threats, harassment, and assault, PANAP has monitored 127 cases with 719 victims, of whom 60 percent were farmers.

As the village of Agbede, the farming settlement in Edelira, and Hacienda Tinang show, these numbers represent the lives and aspirations of rural peoples violently crushed by powerful forces with vested interests in their lands.

More alarming is that, as these particular cases of political repression against peasants show, state forces are often involved. Of the land conflict-related human rights abuses where reports or accounts identified the perpetrators, the police, military, and state-sanctioned paramilitary groups were implicated in 133 cases of killings, 258 cases of arrests and detention, and 49 cases of threats, harassment, and assault.

Greater unrest amid crises

Peasant repression in the context of land conflicts and struggles is a global phenomenon that intensifies amid the worsening crises of the world economy and politics, hunger and food insecurity, and climate and environment.

As global monopoly capitalism navigates its latest bout with an economic crisis lingering since 2008, the world’s wealthiest capitalists are looking for ways to protect their investments and make more money. The financialization of the global economy allows them to turn to assets such as farmlands, even when the likes of giant property holder BlackRock or mega-billionaire Bill Gates have no interest in producing food or engaging in agriculture but merely hedge their other investments or squeeze profits from the land’s value and rent. Through various financial firms, Gates has amassed almost 98,000 hectares of farmlands in the US alone, worth more than USD 690 million.

These financial groups and the capital they manage and represent invest in massive corporate plantations that concentrate lands, displace farmers, and commit violence against rural communities. For example, BlackRock and JP Morgan, along with other financial firms, have almost USD 13 billion in palm oil investments globally. Through his capital management firms, Gates also invests in palm oil, which one study shows is the commodity most exposed to land grabs.

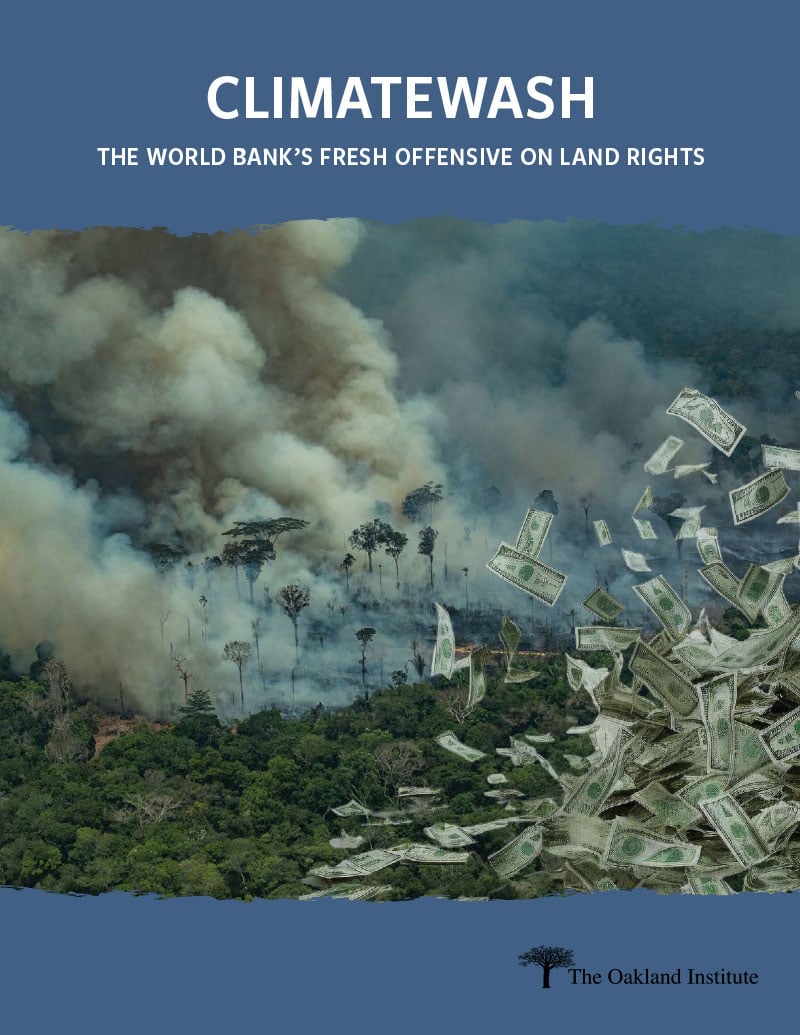

These giant corporations even use the climate crisis they caused to justify more land concentration. They peddle so-called nature-based solutions (NBS) to address the climate crisis, such as through investments in biofuels, green finance, carbon credits, ecotourism, profit-driven conservation, and large-scale infrastructure supposedly for renewable energy.

PANAP has compiled 32 cases of NBS (ongoing or planned), which cover almost four million hectares, to highlight the extent of land grabbing and mass displacement among rural communities worldwide due to the supposed climate actions of monopoly corporations and their local agents. In just five of the NBS projects compiled from Cambodia, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Tanzania, the number of displaced or potentially displaced farmers and indigenous people could reach almost 300,000.

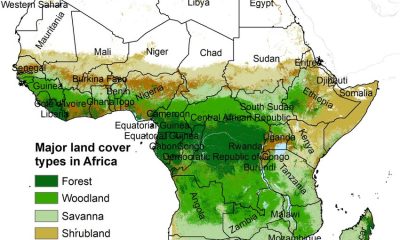

Land concentration is already very severe. In its 2020 report, the International Land Coalition noted that while small-scale farmers run 80 percent of farms, the largest one percent of farming enterprises manage more than 70 percent of farmlands worldwide.

With the wave of more monopoly capital pouring into farmlands through financialization and greenwashing, such concentration can only get even more intense in the coming years and fuel greater rural unrest. (RVO)

Original Source: Farm Land Grab

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK6 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK6 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

NGO WORK5 days ago

NGO WORK5 days ago