Busisiwe Mgangxela, seed saver and agroecologist from the Eastern Cape

Following the United Nations (UN) Food Systems Pre-Summit in Rome last week – a prequel to the Head of State-level Summit in New York, this September – faith communities from across Africa continue to call attention to the wide range of far-reaching consequences of current industrial agricultural models.

An open letter to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation – sent by the Southern African Faith Communities’ Institute (SAFCEI) on behalf of faith leaders on 4 June and endorsed by nearly 500 faith leaders across Africa – emphasizes that the current approach to food security, in the face of the intensifying climate crisis, will do more harm than good on the continent.

SAFCEI’s Executive Director Francesca de Gasparis says, “In addition to damaging ecosystems, threatening local livelihoods and increasing climate vulnerabilities, monocrop farming ignores and undermines smallholder farmers, whose efforts promote sustainable food production and protect the environment.”

“What African farmers need, is support to find communal solutions that increase climate resilience, rather than the top-down profit-driven industrial-scale farming systems proposed. When it comes to the climate, African faith communities are urging the world to think twice before pushing a technical and corporate farming approach,” she says.

Two months after sending the letter, and despite extensive coverage of the pre-summit, which saw more than 100 countries discussing ways to transform national food systems to meet sustainable development goals by 2030, faith leaders in Africa have yet to receive a reply or acknowledgement from the Gates Foundation.

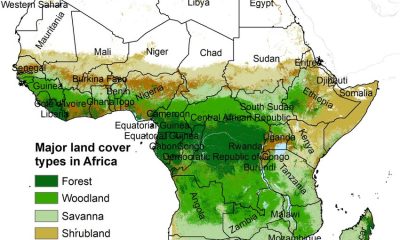

According to de Gasparis, what is currently promoting in sub-Saharan Africa is based on a fossil fuel and extractive business model and reduces farmers to nothing more than “food factories”, rather than meaningful stakeholders and contributors of the global food system.

Consider the N2Africa project, which started with funding from the Gates Foundation. The project, oriented towards a modernisation agenda, will only benefit a few. And, while soil health and nutritional benefits are used to justify investment in legume commercialisation, the actual baseline measurement for success is production for external markets. As a result, local legume crops and varieties that are within existing seed banks and have been grown for generations in ecosystems are bypassed in favour of imported commercial varieties that are developed for industrial feed and processing markets. This threatens local varieties that African farmers and consumers prefer, impacting the affordability of foods, local nutrition, and cultural cooking practices.

Another insidious aspect of the Gates Foundation’s work on the continent is how laws are being altered. The foundation is working to fundamentally restructure seed laws, which protect certified varieties but criminalise non-certified seed. This is particularly problematic for small-scale farmers in Africa, who nourish their families and their communities through seeds that are not certified.

80% of non-certified seeds come from millions of smallholder farmers who recycle and exchange seeds each year, building an “open-source knowledge bank” of seeds that cost little to nothing but have all the nutritional value needed to sustain these communities. In contrast, the approach supported by the Gates Foundation, threatens to replace seed systems diversity and the agro-biodiversity system that is critical for human and ecosystem health and replace it with a privatized, corporate approach that will reduce food systems resilience.

De Gasparis says, “One of the (many) problems with the Gates Foundation approach, where a single cash crop is grown year after year, without rotation and vulnerable to the same pests and disease. This ends up reducing resilience by depleting and destroying natural soil fertility, water resources and our rich biodiversity and genetic capital. Experiences from around the world provide further evidence that industrial mono-cropping will leave African communities worse-off and even more dependent on aid, in the future.”

This style of farming which has been pushed by big commercial farming entities in the US and Europe undermines community-spirited traditions of selecting, saving and sharing seed. It ignores indigenous knowledge regarding local food crop diversity and multi-cropping. One of the results of a business approach that centralises control of production systems, is that land and profits end up in the hands of a small elite minority. This not only threatens the agency of most producers in Africa, who are small-scale farmers – those whose farming practices are based on historical and cultural knowledge and understanding of their ecological landscapes – it also reduces production of local nutritious foods and medicines.

“We saw that many of these same issues were at stake during the farmer protests in India and the same issues are valid in Africa. Around the globe, agribusinesses are trying to convince governments and financial institutions that they hold the answer to the world’s hunger problems, and that they can resolve these in a sustainable, climate -friendly way. We’ve seen that movie before and it never works out fairly for the small farmers who remain the life blood of much of Africa and who are indispensable to its future,” says de Gasparis.

According to SAFCEI’s Climate Justice Coordinator, Gabriel Manyangadze, “We’ve seen from its initiatives in Africa that the Gates Foundation puts its full faith in technological fixes without seeking to address the vitally-important issues of morality and political economy involved. As such, the Foundation’s approach supports a dominance of multinational corporations over African-led food production systems. And in the Gates Foundation’s unwillingness to listen – we see a self-confidence bordering on arrogance, exactly the kind of ‘white saviour’ mentality of colonialism that Africa neither needs nor wants.”

“People of faith, with reverence to the Almighty and with concern and respect to creation, must stand for agroecology. Faith leaders across Africa are witnessing the negative impact of industrialised farming to the land and in their communities. The data shows that industrialised mono-crop farming practices and food systems do not and will not provide the people of Africa with a nutritious and chemical-free, nor a diverse and culturally-appropriate diet that is affordable,” says Manyangadze.

“That is why hundreds of religious leaders from Africa with solidarity from organisations have called on the Gates Foundation to re-think its approach to farming in Africa. We appeal to those who truly want to do good in Africa, to start by listening to the farmers that you claim you want to help. Work with them because they are already developing appropriate solutions for their contexts. There are better ways to become climate resilient, than what you are proposing.”

According to SAFCEI, more investment and support must be given to the small-scale farmers around the world who are working to build alternative food systems that are socially just and ecologically sustainable and learn from them. It says it wants to see organisations, like the Gates Foundation, use their influence to ensure that smallholder farmers have ample support. This includes assisting governments to implement holistic, supportive strategies. And rather than giving ownership to multinational corporations, help local communities have a real stake in policy negotiations. This approach also requires a commitment to land reform and gives communities agency and power over their own circumstances for self-determination.

“Our call is for the Gates Foundation (and others) to stop pushing profit-driven industrial agriculture that impose technologies and seeds that are controlled by companies with vested interests, under the guise of a green “revolution”. We call on Northern actors to instead move towards sustainable and agro-ecological approaches that work with farmers to achieve climate resilience. Agroecological strategies such as intercropping, the “push-pull” system and integrated pest management that show efficacy in the field and build ecosystem climate resilience. These are already being implemented in both the Americas and Africa and do not further indebt farmers or compromise their health, or that of their environment,” says Manyangadze.

“As the faith communities and farmers of Africa, we want regenerative and agroecological approaches that do not destroy biodiversity on the continent and that will provide a just distribution of food for all. Such an approach requires the Foundation and others to look for solutions not only from science, but also in the knowledge, heritage, experience and needs of African farmers,” he concludes.

“Religious communities around the globe have no faith in the Gates Foundation’s corporate agribusiness approaches which threaten small farmers, degrade soil and water, concentrate ownership by regional and global elites, and reduce everything and everyone – from farmers to soil to seeds to livestock – to soulless commodity. We believe in a bottom-up approach that respects small farmers, protects land from toxic inputs, and strengthens local communities.” Rev. Fletcher Harper (U.S.A.), Executive Director, GreenFaith.

Speaking from her experience on the ground, Busisiwe Mgangxela – an agroecological farmer from the Eastern Cape province in South Africa – says, “What I love about agroecology is that it takes care of the soil and environment, and in turn, the people. It looks at ecology, diversity, and sustainability by incorporating the principles of organic farming: care, health, ecology, and fairness. Sustainable agriculture works to conserve our natural resources, while also considering the health of the people.

This style of farming allows us to plant a variety of crops, using organic fertilisers to feed the soil and natural pest control methods, to avoid chemicals damaging our soil and water sources. Agricultural Industrialisation is taking away the nutrients from the soil that produce good crops. What we need to focus on is sustainable production and sustainable consumption, as part of our efforts to mitigate climate change and reduce our footprint on Mother Earth.”

Celestine Otieno, a Kenyan permaculture farmer shared some of the challenges facing farmers in Kenya. She says, “Farmers have become wary of programs that promote monoculture and chemical-intensive farming. Farmers have lost control over indigenous seeds and farming systems and are now saying that they are being held hostage on their own farms. The Gates Foundation is pushing to expand industrial agriculture. My question is: is agricultural industrialisation leading to food security or to food slavery?”

Rev Wellington Sibanda says, “The churches in this area that I serve, are mostly in rural communities. They provide a sense of hope for those trying to make a living on the edge of Northern KwaZulu-Natal. Many of them must survive as seasonal workers in the farming areas, and others as subsistence farmers. Our churches are supported by the sweat of these mostly impoverished communities, who are far away from the industrialized markets of the cities.”

“Under economic imperialism, almost all the crops and goods that are produced in this region are under the control of multi-national corporations. Immediately after they are harvested or dug from the belly of the Earth, they are exported to regional and overseas markets. This affects the livelihoods, not just of the people from around here, but throughout Southern Africa.”

“Agro-ecological farming practices increases sustainable agricultural productivity and the income of smallholder women farmers.”

Ange David from GRAIN in Côte d’Ivoire says, “People in Ghana are fighting against policies pushed by institutions like Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). We can call it agro-colonialism. We need to put pressure on AGRA and the Gates Foundation. They are trying to change government seed policies to benefit corporations.”

Anne Maina from BIBA Kenya believes that the future is in agroecology and supporting smallholder farmers to produce food for current and future generations, in the process, taking care of the soil and natural resources.

Maina says, “Seed laws are being changed across Africa, to the detriment of the people. $1 billion has been allocated to Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), but the impacts are really low. Soil fertility in Africa is going down due to increased fertiliser use and punitive seed laws are marginalising farmers. When we demanded evidence of the positive impacts they claim to come from their approach, they would not give it to us. Till today, we have no solid evidence. It would have been much more productive had we had focused on agroecology. This is why we are pushing for it now.”

Neth Daño from ETC Group Philippines says, “This philanthrocapitalism from the likes of the Gates Foundation and others, are enabled by government policies. We are inspired by resistance in Africa because we have seen this technofix approach disempower traditional farmers in Asia and Africa.”

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS1 week ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS1 week ago

SPECIAL REPORTS AND PROJECTS1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK6 hours ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK6 hours ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 hours ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK3 hours ago

NGO WORK1 day ago

NGO WORK1 day ago