Joint Statement Response by Advisers of PAPs to the DRS Follow-Up Report on the Uganda KIIDP-2 Case

KAMPALA, 25th NOVEMBER 2025

Introduction

On 30th October 2025, the World Bank’s Dispute Resolution Service (DRS) published its final Follow-up Report on the Uganda KIIDP-2 case, a community-led complaint regarding forced evictions and project-related harms under the Kampala Infrastructure and Institutional Development Project. The case began in 2021 and closed in 2023.

We welcome the publication of the Follow-up Report as it provides important reflections on dispute resolution practice. We appreciate that feedback from stakeholders, including some of our own, was incorporated into the Report. However, the Report presents an overly positive narrative that fails to reflect critical issues experienced by community members negatively impacted by the KIIDP-2 project. These omissions not only distort the record but undermine the legitimacy and objective of the accountability process and learning.

Gaps in Report

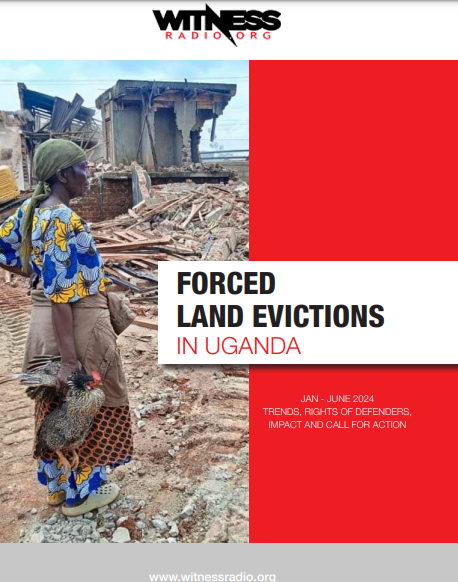

Project harms continue: It is paramount to begin here. The affected community filed a complaint to the Inspection Panel of the World Bank in 2020 to complain about harm they were experiencing with the ongoing KIIDP II project. The project designers and implementers failed to engage meaningfully with people who would be impacted by the project, and as a result, there was inadequate compensation for negative impacts, health risks and other hazards were associated with mismanagement of the drainage channel, and people lost their livelihoods. Over five years later–and even after a mediation process–the issues persist. The project remains incomplete even after the project closeout date. Clogged passages with dirt, persistent flooding of peoples homes and farms with dirty water, lack of access to homes, and incomplete infrastructure remain unresolved. The posture of the Follow-up Report assumes implementation is complete and everything is well, but the reality couldn’t be further from that.

No livelihood restoration: Livelihood support was a core demand from community members and a central topic throughout the mediation. Although interim agreements were reached on this issue, they were not included in the final agreement, and no livelihood programs have since been implemented. The community’s health, safety, and economic conditions continue to deteriorate as a result.

Women’s issues ignored: Gender-specific harms raised in the complaint and during the case process were never addressed and are completely absent from the final report.

Retaliation, intimidation, and threats of eviction: The report fails to acknowledge threats, harassment, and attempted evictions faced by community members during the process.

The process felt coerced and rushed: The Follow-up Report fails to capture DRS’ own challenges in managing the timelines to ensure a successful outcome. Although the mediation process spanned 18 months, community members report that they felt pressured to sign the agreement on the final day. In part this is because there was confusion about whether the dispute resolution process had officially concluded, and representatives and advisors were not informed in advance that the signing would take place that day. The Follow-Up Report also fails to capture the serious concerns associated with the signing of the agreement that led the community to feel coerced to sign the agreement. For example, the presence of government security officials at the signing created an intimidating atmosphere, further contributing to the sense of coercion.

Undermined decision-making: In the final stages, the DRS changed the previously agreed community representation and decision-making structure, sidelining duly elected representatives and diminishing the voice of minority or dissenting perspectives. The DRS made a unilateral decision–on the day of signing of the agreement–that the representatives previously elected by impacted community members were no longer going to make decisions on behalf of the community, and that instead, every member of the community was required individually to sign the agreement if they wanted to benefit from its provisions. Furthermore, the DRS had earlier communicated that if the agreement was signed, no unresolved issues could be referred to the compliance process, effectively discouraging individuals from dissenting or withholding their signature.

Confidentiality limitations: Unreasonably strict confidentiality restrictions during the mediation process limited community representatives’ ability to consult with other community members, the media, and allies. This lack of openness undermined transparency, community-wide participation, and meaningful ownership of the process. Towards the end of the process and during the implementation phase, the DRS interpreted these confidentiality provisions in a way that denied advisors access to key documents, including the mediation agreement and drafts of the Follow-Up Report. This made it extremely difficult for the advisors to support the community with timely and informed guidance. The removal of the Implementation Committee on the day of signing the agreement, without mutual agreement or any formal communication, further isolated the advisors. As a result, they were unable to monitor implementation or receive feedback through project-affected people (PAPs), with DRS insisting that the agreement remained confidential. The continued denial of access under the guise of confidentiality infringed on the community’s right to adequate representation.

Exclusion from Inspection Panel referral: The report omits that requesters were excluded from bringing unresolved issues to the Inspection Panel for investigation. This shift contradicted earlier expectations and closed off a key accountability route. Read more here.

To support transparency and learning, we commissioned an independent consultant to gather community feedback on the process, outcomes, and roles of various actors. Once complete, this analysis will be shared with the DRS and the World Bank to inform future DRS processes and strengthen accountability for other communities.

Conclusion

We believe in the potential of dispute resolution to provide meaningful remedy, but to realize that potential, there must be bold, transparent, and inclusive implementation. The DRS must account for all aspects of the mediation process and its outcomes. Livelihoods, gender-specific harms, and reprisals are not peripheral issues; they are central to justice, and they are left unresolved.

We thank the DRS for its work and call for further dialogue to ensure the spirit of the agreement is honored, and the dignity of the Kawaala community upheld.

Witness Radio

Accountability Counsel

Statement: 19.11.25 Statement Re DRS Report

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK7 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK1 week ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 days ago