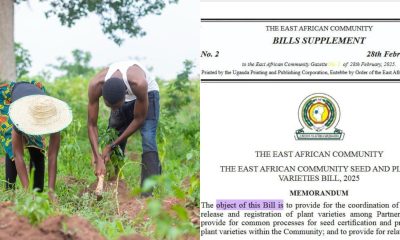

The International Planning Committee on Food Sovereignty’s (IPC) Working Group on Agrobiodiversity is in Rome this week to participate in the Open-Ended Working Group negotiations. The aim is to enhance the functioning of the Multilateral System, and to fight the private interests that try to get rid of their obligations as set by the FAO Plant Treaty 20 years ago. La Via Campesina members are also part of this group in the Rome meeting, to defend peasants’ rights to seeds and genetic resources, against the biopiracy of the seed industry supported by rich countries.

What is the Multilateral System?

The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA) was adopted by the Thirty-First Session of the Conference of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations on 3 November 2001. The Treaty’s Multilateral System, puts 64 of our most important crops – crops that together account for 80 percent of the food we derive from plants – into an easily accessible global pool of genetic resources that is freely available to potential users in the Treaty’s ratifying nations for some uses.

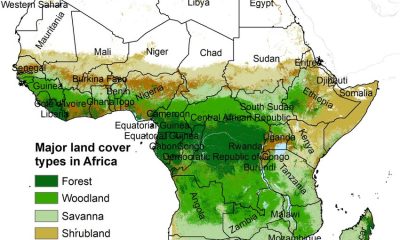

Most of these samples have been collected from the fields of the farmers who selected them and reproduced them from generation to generation. They represent nearly 40% of the samples stored in germplasm banks. Sixty percent of them come from national collections, 5% from private collections and 35% from international seed banks (CGIAR).

Agriculture needs an enabling access and benefit-sharing system. Such a system should recognize interdependence, trigger the exchange of genetic material of plant origin on a multilateral and facilitated basis. But most importantly such a system must instill fairness and recognize that the global pool to which access is facilitated is continuously enriched by the contributions of farmers worldwide.

A practical and fair access and benefit-sharing system must ensure that genetic resources continue to flow worldwide, while those individuals who selected and conserve those resources are adequately rewarded.

How the access to the Multilateral System works?

The mechanism for obtaining specific genetic resources is through a standardized contract referred to as a “Standard Material Transfer Agreement (SMTA). The SMTA is a binding private bilateral contract between the provider and recipient which states the terms and conditions for use of the genetic resource.

According to the IPC, “Governments, when they negotiated the mechanism, limited the application of the Multilateral System to resources that they could manage and control directly, since most of them are held in national germplasm banks. Plant genetic resources in the public domain should be considered as those which are not the subject of intellectual property rights…[]..Facilitated access through the multilateral system is for the purposes of utilization and conservation for research, breeding and training for food and agriculture… Such purposes do not include chemical, pharmaceutical and/or other non-food/feed industrial uses.”

How the benefit sharing mechanism should work?

The ITPGRFA sets forth the basic structure of monetary benefit sharing under the Multilateral System, but it is the SMTA that defines how much is to be shared.

The beneficiary who markets products (containing PGRFA or genetic parts or components of PGRFA from the Multilateral System) with restrictions has two alternative options for monetary benefit sharing:

- he or she pays 0.77 per cent on the net sales of the commercialized product with restrictions for a period corresponding to the duration of such restriction (for instance, 20 years in the case of intellectual property rights-based restrictions), OR

- he pays 0.5 per cent on the sales of all PGRFA products of the same crop to which the accessed material belongs for 10 years (renewable).

In this second case, the payment is higher and in return, the beneficiary can access all the genetic material of that crop without paying for other SMTAs.

SMTA-generated monetary benefits flow into a multilateral fund – namely the Benefit Sharing Fund. This fund is also open to direct contributions and benefits arising from the use of PGRFA that are shared under the multilateral system would flow primarily to farmers, especially in developing countries, who conserve and use PGRFA in a sustainable manner.

However, these payments are optional when commercialized seeds are available “without restriction for research and breeding”, i.e. when they are free of any intellectual property rights or covered by a plant variety right that only limits farmers’ rights and not breeders’ rights.

But industry’s not paying its share

For 15 years, no payments have been made. Seed companies holding patents restricting facilitated access (for research and breeding), which are the only ones subject to mandatory payments, do not pay by taking advantage of the absence of a traceability requirement for PGRFA trade to avoid reporting their use of PGRFA from the Multilateral System. At the time of the blockchain, however, such traceability is technically possible and exists within each company. But industry hides behind trade secrets to provide no information.

In the absence of contributions from beneficiaries, some States and private individuals made voluntary payments to initiate the Fund. Over the past years, the Fund has only raised around $10 million. In comparison, the Global Crop Diversity Trust Fund for ex situ conservation (in gene banks) mobilized $314 million from contributions from rich countries and industrial foundations. It is therefore not the lack of money that explains the negligence of the Benefit Sharing Fund, but the political choice not to pay for the work of farmers in selecting, retaining and renewing PGRFA.

To get out of the circumvention of benefit sharing by beneficiaries, the IPC Working Group on Agrobiodiversity proposes to make payments mandatory through two mechanisms.

Access to the sole information on a genetic sequence contained in a PGRFA allows today, without the need to access the physical PGRFA itself, to reconstitute this sequence in the laboratory with synthetic biology or to identify it in other plants for integration into new seeds with new biotechnologies, or by crossbreeding if it has been identified in sexually compatible plants. Such information is compiled in huge databases of data that are freely accessible via the Internet. Whatever the conclusions of current international discussions on regulating access to such genetic information for benefit sharing, no State can now control free access to the databases that compile it on the Internet.

So, while the seed industry has benefited enormously from this facilitated access to the Treaty material, they never shared the benefits equitably and the majority of States continue to adopt intellectual property laws, which violate farmers’ rights. In response to this failure, the Treaty began work in 2013 to “improve” its functioning. The Ad Hoc Open-Ended Working Group to Enhance the Functioning of the Multilateral System of Access and Benefit-Sharing was created.

Over the last five years no agreement has been reached, because differences remains between developing and reach countries. After 20 years since the Treaty entered into force, its survival is threatened by the seed industry’s refusal to pay its debt and respect farmers’ rights.

Digital Sequence Information – DSI

Recent advances in biotechnology and genetic sequencing enormously increase that risk. In fact, they allow industry plant breeders to stop working by observing the physical characteristics of plants, and to analyze on their computer screens the digital representation of their genetic sequences. Access only to the digital information of a genetic sequence (Digital Sequence Information – DSI) contained in a PGRFA now allows, without the need to access the physical PGRFA itself, to reconstitute this sequence in the laboratory with synthetic biology or to identify it in other plants for integration in new seeds with new biotechnologies, or by crosses if it has been identified in sexually compatible plants. Rich countries and industry consider that this DSI is not a genetic resource subject to prior consent and benefit-sharing obligations of the Nagoya Treaty or Protocol.

Industrialized countries make these claims even if the Treaty is very clear when it refers to the access to the physical material and the “associated information”. However, there is no agreement on this and rich countries do not take a step behind this red line.

Another main unsolved (and maybe unsolvable) issue is the payment rates in the subscription system. The industrialized countries, especially Canada, Germany and Switzerland want to set a very low payment rate of 0,011% of the sales of the material covered by the Multilateral System of the Treaty, while the payment requested by developing countries is 0,1%.

Source: La Via Campesina

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK4 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK2 weeks ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

MEDIA FOR CHANGE NETWORK5 days ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago

NGO WORK2 weeks ago